CHAPTER three The Thorax

THE PHARYNX, LARYNX, AND HYOID APPARATUS

Normal Appearance

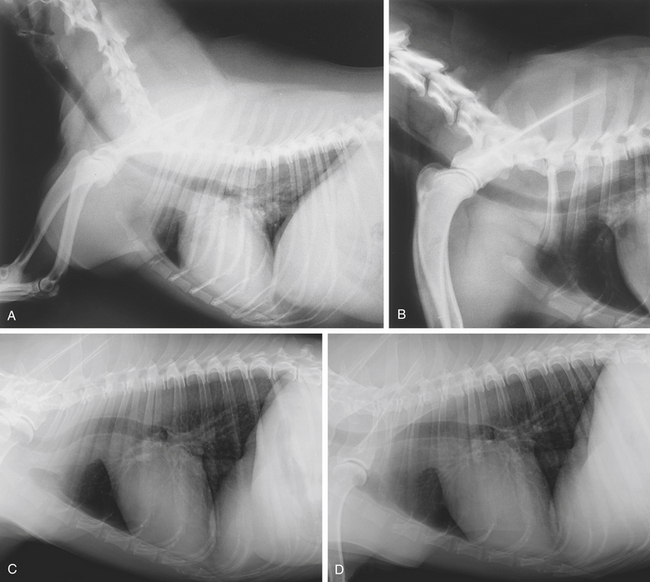

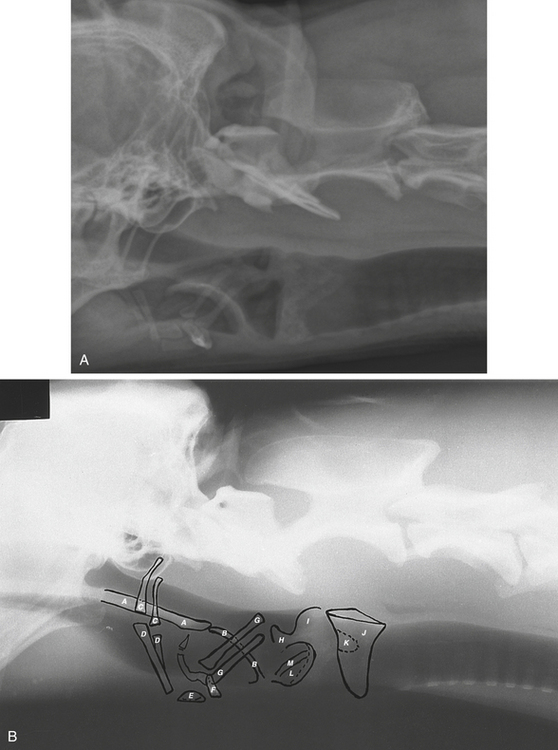

The pharynx and larynx are readily identifiable on properly exposed lateral views of the neck (Figure 3-1, A and B). On ventrodorsal projections, the larynx overlies the cervical vertebrae, and most of its detail is lost. Good radiographs will show the soft palate, hyoid apparatus, epiglottis, and cricoid cartilage. The diameter of the larynx is somewhat wider than that of the trachea (Figure 3-1, A and B).

Abnormalities

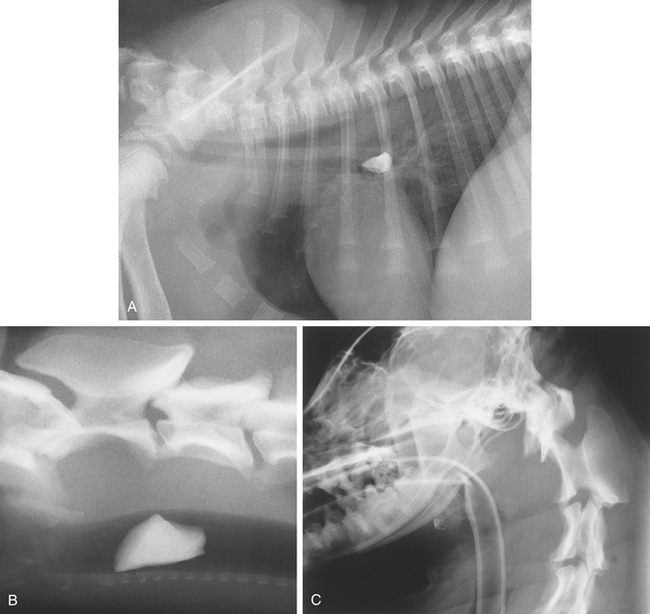

Abnormalities of the larynx are usually diagnosed by methods other than radiologic. Displacement of the larynx, compression, or calcification may result in visible radiographic changes. Fractures of the hyoid bones occur (Figure 3-1, C). Foreign bodies or mass lesions in the pharynx or larynx are usually visible because of surrounding contrasting air (Figure 3-1, D).

Pharyngeal Dysphagia and Cricopharyngeal Achalasia

Cricopharyngeal achalasia results from failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax during swallowing or from lack of coordination of the mechanisms involved in swallowing. The clinical signs are similar to those seen in pharyngeal dysphagia. A barium study shows retention of barium in the pharynx and cervical esophagus. On fluoroscopy, pharyngeal contractions are seen to force the barium against the caudal wall of the pharynx, with only a small amount of barium entering the esophagus, where it tends to remain. Barium may come down the nose or enter the larynx or trachea. Failure of the cricopharyngeus muscle to relax can be treated surgically. However, cricopharyngeal myotomy is contraindicated in other disorders of this region. Hence, accurate diagnosis is important.

Laryngeal Paralysis

As a result of paralysis of the laryngeal muscles, the laryngeal airway does not open adequately during respiration. Clinically, there is a moist cough and, in more severe cases, a loud inspiratory noise.

Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome

This is seen in brachycephalic dogs as a combination of elongated soft palate and various laryngeal abnormalities such as paralysis. The pharynx is small, and the hyoid apparatus is directed vertically (Figure 3-1, E and F).

THE TRACHEA

Radiography

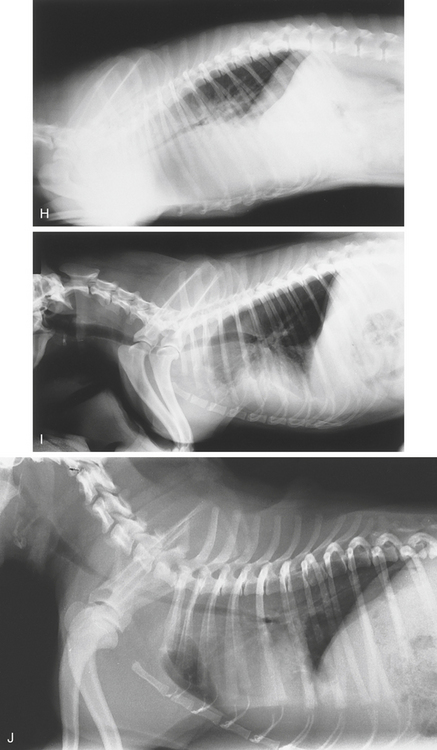

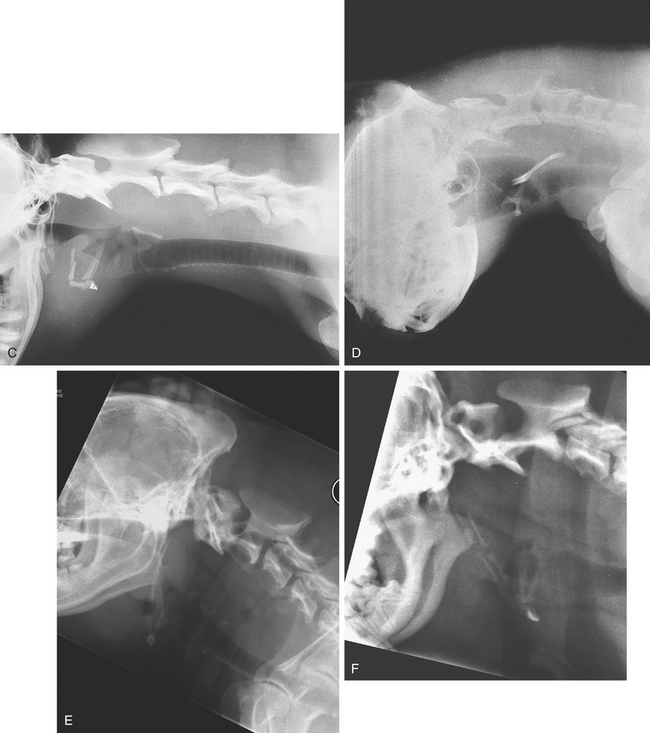

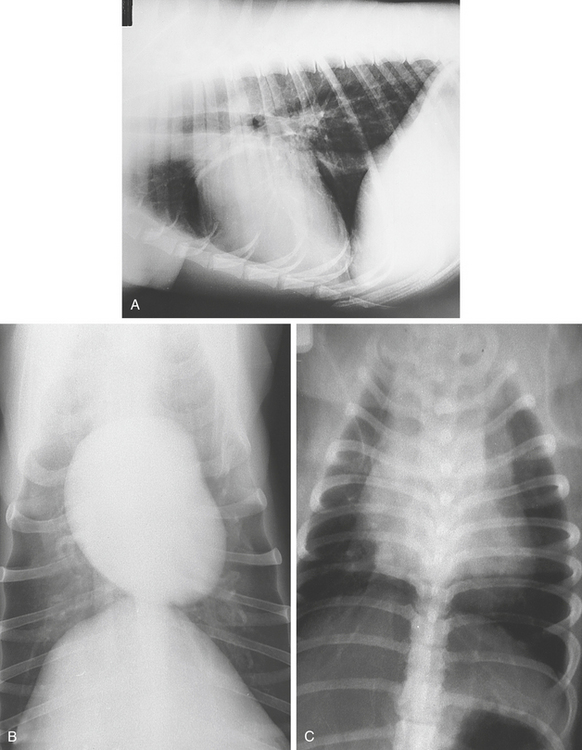

Lateral and ventrodorsal views of the neck and thorax are necessary for routine examination of the trachea. Oblique views are helpful in demonstrating the trachea without superimposition of the vertebrae and sternum, as occurs on the ventrodorsal view. Care must be taken that no rotation of the thorax is present on lateral views; this will cause an apparent displacement of the trachea. The neck should be comfortably extended. Overextension results in a pseudonarrowing at the thoracic inlet, whereas flexion of the head or neck or elevation from the table top will cause tracheal deviation in the cranial thorax (Figure 3-2, A and B).

Normal Appearance

The trachea is visualized more clearly on lateral views. The air within it acts as a contrast medium, contrasting with the soft tissue opacity of the neck muscles and structures within the mediastinum. On ventrodorsal or dorsoventral views, the trachea is more difficult to see because of the superimposed vertebrae and sternum. The trachea, in the cranial mediastinum, lies to the right of the midline, becoming centrally placed at its bifurcation. On the lateral view, it forms an acute angle with the line of the thoracic vertebrae. The angle is greater in dogs with a deep, narrow thorax and more acute in dogs with a shallow thorax. A rounded lucency over the base of the heart marks the point of bifurcation. It represents the origin of the right cranial lobe bronchus seen end-on. A second rounded lucency may be seen that represents the origin of the left cranial lobe bronchus. The trachea curves somewhat ventrally toward its bifurcation between the fifth and sixth ribs. Only the primary bronchi near the bifurcation are recognizable on normal radiographs. Smaller bronchi cannot be identified. The diameter of the tracheal lumen varies slightly during inspiration and expiration. It is slightly smaller than the width of the larynx. It has been suggested that the width of the lumen should be three times the width of the proximal third of the third rib. Alternatively, the tracheal diameter can be expressed as a ratio to the thoracic inlet as measured on the lateral view. Normally the trachea is approximately one fifth the depth of the thoracic inlet (Figures 3-2, A, and 3-3, D).

Abnormalities

Displacement

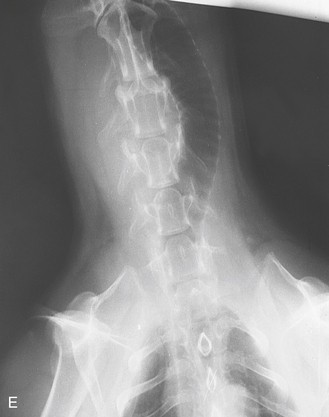

Before making a diagnosis of tracheal displacement, one must be sure that the animal has been positioned correctly. Undue extension may result in the trachea appearing compressed at the thoracic inlet (Figure 3-3, A). Extreme flexion of the neck during radiography may result in a ventral displacement of the trachea in the cranial thorax (Figure 3-3, B and C). Dorsal displacement may be seen with lateral or ventral flexion of the neck. This results in artifactual displacement of the trachea in the cranial mediastinum, simulating a mass (Figure 3-3, C and D). Rotation of the thorax on the lateral view will cause an apparent elevation. Some deviation of the trachea to the right is often seen in normal dogs in the cranial thorax. It may be more pronounced in brachycephalic breeds (see Figure 3-29, G). A ventrodorsal or dorsoventral view is required to demonstrate deviation in the lateral plane (Figure 3-3, E).

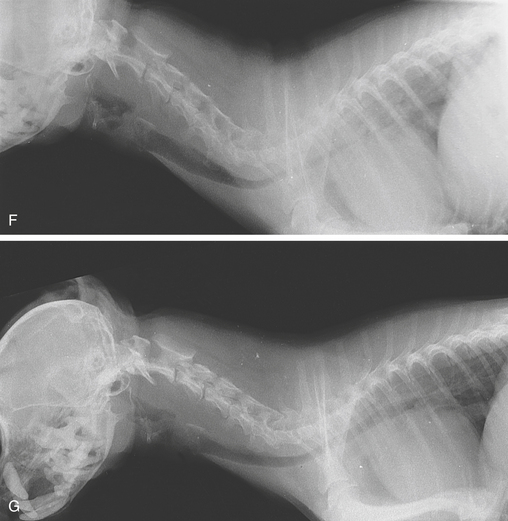

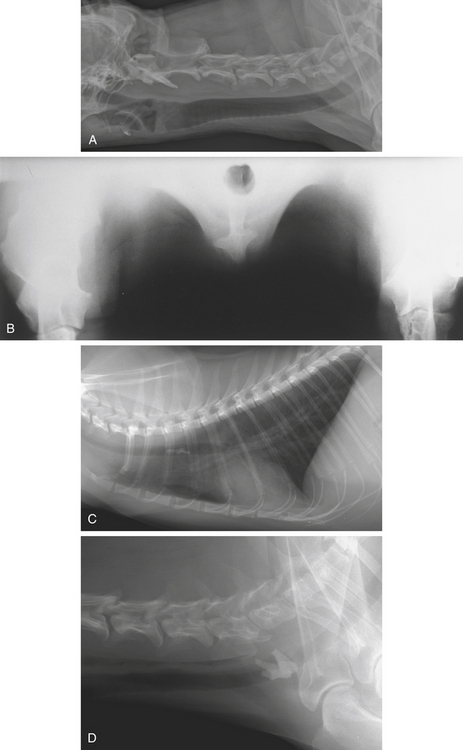

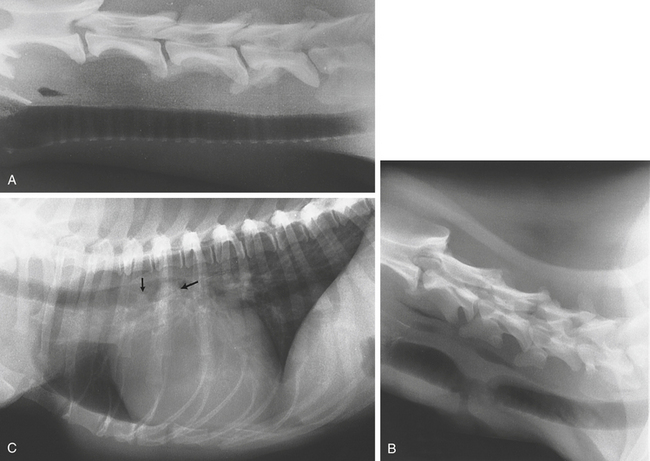

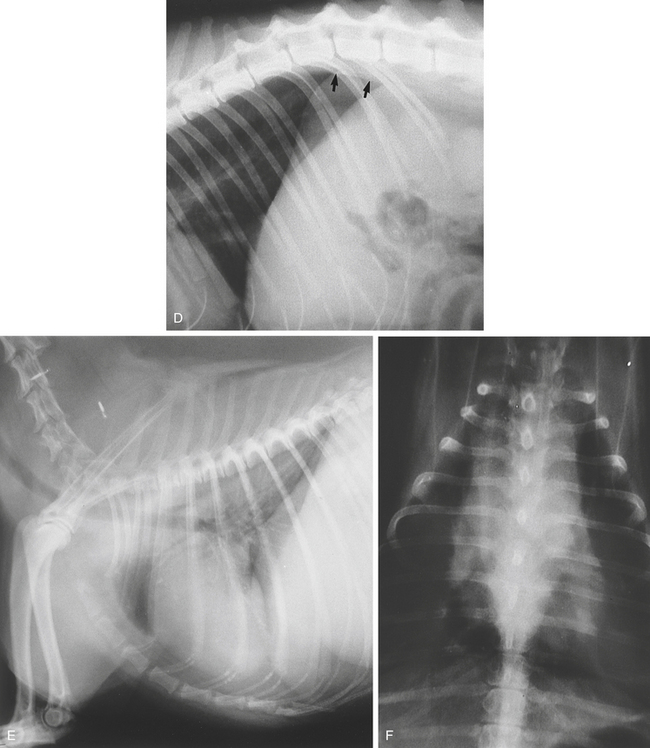

Figure 3-3 A, Pseudonarrowing of the trachea at the thoracic inlet from hyperextension of the neck. B, A lateral view of the thorax with the neck flexed shows a slight bend in the trachea at the thoracic inlet from hyperflexion. C and D, Artifactual tracheal displacement in a dog. C, When the initial radiograph was obtained, the patient’s neck was partially flexed. There is dorsal displacement of the thoracic trachea, just cranial to the aortic arch. This displacement mimics dorsal tracheal deviation associated with a cranial mediastinal mass. D, A second radiograph was obtained with the dog’s head and neck in a neutral position. The trachea is now seen to be in a normal position, with no evidence of displacement. E, The trachea is displaced to the left by a mass in the neck. This was a thyroid mass. F and G, Tracheal collapse. A 7-year-old Yorkshire Terrier had been coughing in violent spasms for several months. Lateral studies of the trachea in expiration (F) and inspiration (G). The intrathoracic tracheal lumen is markedly narrowed at expiration, and the difference between the two phases of respiration is well demonstrated. H and I, A 9-year-old Boston Terrier was depressed, cyanotic, and tachypneic. H, A lateral radiograph shows severe narrowing of the intrathoracic trachea. There is widespread infi ltration of the lungs from hemorrhage. There is some air in the cervical esophagus. This was submucosal hemorrhage in the trachea caused by anticoagulant poisoning. I, Four days later there is almost complete resolution of the condition. (This is the same case as Figure 3-25, I and J.) J, This 1-year-old Pug had a history since birth of repetitive collapse after exercise. The tracheal lumen is grossly narrowed throughout its length. Diagnosis: tracheal hypoplasia.

Collapse

Tracheal collapse affects the smaller breeds of dogs in middle to old age. It may be acquired or congenital. The congenital form manifests itself in later life. The clinical signs comprise varying degrees of respiratory distress and a paroxysmal, chronic, dry “goose honk” cough. Because the usual type of collapse is in the dorsoventral plane, lateral radiographs are the most informative. Both inspiratory and expiratory radiographs of the full length of the trachea should be made with the forelimbs at right angles to the spine. A skyline or tangential view of the thoracic inlet with the dog in sternal recumbency and the head and neck extended dorsally is occasionally useful (see Figure 3-2, B). Extreme care should be taken because such positioning may exacerbate the clinical signs.

Radiologic Signs

Hypoplasia

Congenital hypoplasia (congenital stenosis) is seen in some brachycephalic breeds such as the English Bulldog and the Bullmastiff. It is occasionally seen in other breeds such as the German Shepherd, the Labrador Retriever, and the Basset Hound. It is rare in cats. The tracheal lumen size is grossly narrowed, usually throughout its length. The diameter may be less than half that of the larynx or less than the width of the proximal third of the third rib. With hypoplasia, there is no variation in diameter on inspiratory and expiratory radiographs or during fluoroscopy (Figure 3-3, J). Aspiration pneumonia may be a complicating factor. The trachea may be narrowed as a result of intramural hemorrhage (Figure 3-3, H and I).

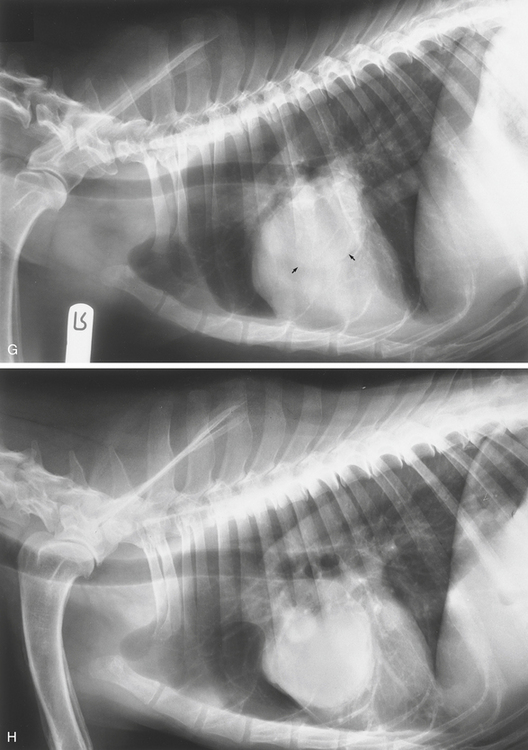

Calcification

Calcification of the tracheal rings is sometimes seen in older dogs, particularly in the chondrodystrophoid breeds. It does not appear to have any significance (Figure 3-4, A).

Stenosis

Stenosis, or narrowing of the trachea, may be seen on lateral studies. It may occur in dogs or cats after laceration, direct blunt trauma, or bite wounds (Figure 3-4, B).

Oslerus osleri

Irregularities in the tracheal lumen and soft tissue opacities projecting into it, with increased peribronchial radiopacities in the perihilar area, have been described in association with Oslerus osleri (Filaroides osleri) infestation. Diagnosis is more certainly achieved by demonstrating larvae in fecal samples or tracheal washings or by endoscopy (Figure 3-4, C).

Obstruction

Foreign body obstruction of the trachea is not common. The main clinical finding is sudden bouts of severe coughing. The air-filled trachea provides a good contrast background against which a foreign body can usually be seen (see Figures 3-2, C and D, and 3-5, A and B). If the foreign body is radiolucent, endoscopy may be more informative. Obstruction of the trachea may result in hyperinflated lung fields due to a ball-valve effect, resulting in difficulty in expelling air. If a foreign body passes into a bronchus, the resulting atelectasis may obscure it. No air bronchograms will be seen in the atelectatic lobe because the presence of fluid obliterates contrast between the bronchi and the lung. Flexion of the neck with an endotracheal tube in place may cause kinking of the tube and obstruction of the airway (Figure 3-5, C).

THE THORACIC CAVITY

THE SKIN

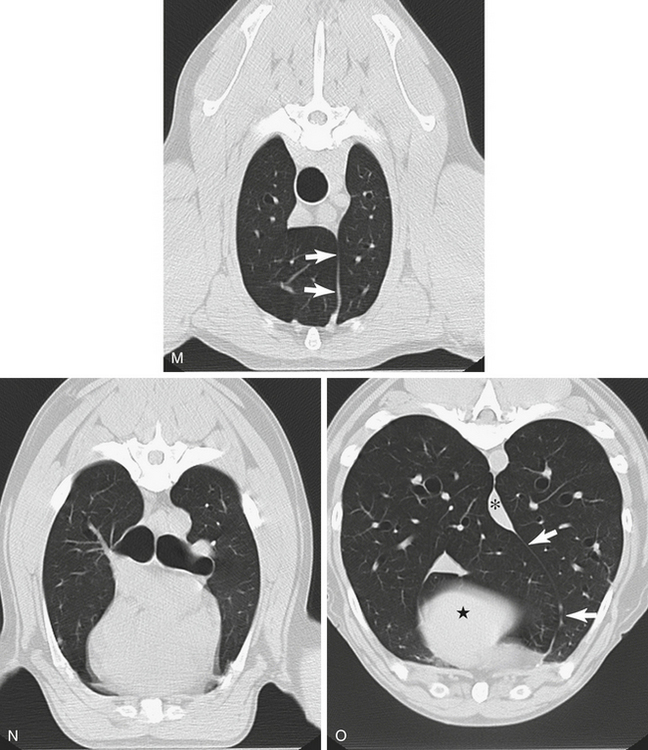

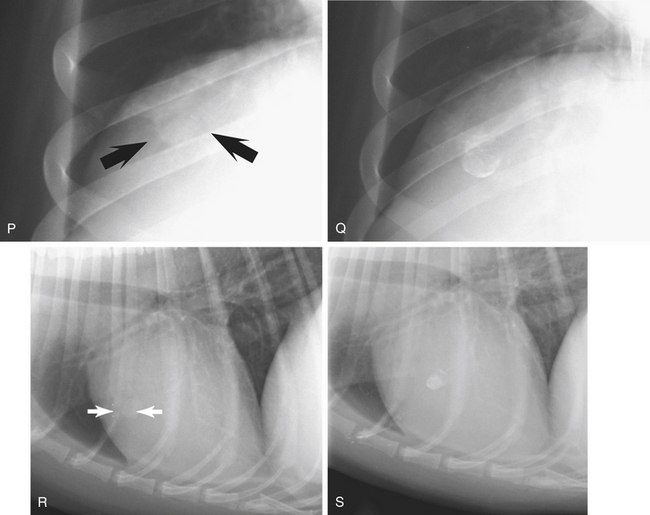

The skin forms part of the background opacity on radiographs of the thorax. Foreign substances on the skin may cause radiographic opacities within the thoracic shadow, thus simulating abnormalities. The skin should be examined visually and manually in cases of doubt. Prominent skinfolds often cause well-defined lines that traverse the thorax in a craniocaudal direction on ventrodorsal views. These lines may seem to represent lung edges and so lead to a false diagnosis of pneumothorax and collapsed lungs. Such skinfolds can usually be traced out beyond the confines of the thoracic cavity. On the lateral study, they may also be seen on the ventral third of the thorax associated with the forelimbs (see Figure 3-23, I and J). Teat shadows or skin masses superimposed on lung shadows should not be mistaken for intrapulmonary opacities (see Figure 3-6, P to S). Subcutaneous emphysema makes the thoracic cavity appear more radiolucent and can cause linear streaks or a honeycomb effect. The air-filled lungs provide good contrast for the demonstration of intrathoracic structures.

Radiography

For routine examination at least two views are necessary: a lateral view and a dorsoventral or ventrodorsal view. A comprehensive study should include two opposing lateral views and either a dorsoventral or a ventrodorsal view. Radiographs should be made during the inspiratory pause because when the lungs are filled with air, maximal contrast is achieved between the different structures within the thorax. The beam should be collimated to include the entire thorax from a point 2 cm cranial (just cranial to the manubrium) to the first rib to a point caudal to the first lumbar vertebra (to the midbody of the second lumbar vertebra). A grid should be used if the thorax measures 15 cm or more in thickness.

On films made at expiration, the lung fields appear more opaque, and much of the pulmonary vasculature detail is lost. But expiratory films may be of value in pulmonary emphysema, in which air cannot be expelled from the lungs. In addition, expiratory films are useful for the identification of small volumes of pleural air or fluid and bronchial or tracheal collapse (see Figure 3-3, F).

Lateral View

The animal is placed in lateral recumbency. The forelimbs are drawn cranially and positioned parallel to one another. This position prevents superimposition of the triceps muscles on the apical portions of the cranial lung lobes. The sternum should be supported and should be on the same level and parallel to the thoracic vertebrae so that there is no rotation of the thorax relative to the incident x-ray beam. The neck is extended, or at least not flexed. The beam is centered at the fifth intercostal space, usually at the caudal edge of the scapula. There is little difference between radiographs made in left lateral recumbency and those made in right lateral recumbency. Right lateral recumbency may be preferred because in this position the phrenicopericardial ligament restricts movement of the cardiac apex toward the dependent side.

If pathology is suspected in one lung, that lung should be uppermost because the dependent lung does not inflate fully, and contrast in it is therefore diminished. For this reason, two opposing lateral studies are needed to fully evaluate both lungs. Standing lateral views are occasionally useful if pleural fluid or air is suspected. For this view, the cassette is positioned along the thoracic wall with the animal in the standing position. A horizontal beam is used, centered on the fifth intercostal space. A lateral view, using a horizontal beam and with the animal in sternal recumbency, is an alternative. Dorsal recumbency using a horizontal beam is occasionally used to examine the ventral thoracic region, but this position requires care in animals with compromised respiration.

Dorsoventral and Ventrodorsal Views

The cardiac outline is less distorted on the dorsoventral view, that is, with the animal in sternal recumbency. If the cardiac shadow is the main item of interest, the dorsoventral view is preferable. The vessels to the caudal lung lobes are better seen on this view. To obtain a dorsoventral view, the animal is placed in sternal (ventral) recumbency with the elbows abducted and the forelimbs drawn slightly forward. The hindlimbs are flexed, with the hocks resting on the table. The head is positioned between the forelimbs on the midline. The thorax should not be rotated. The thoracic vertebrae should overlie the sternum. The beam is centered over the caudal edge of the scapula.

Normal Appearance

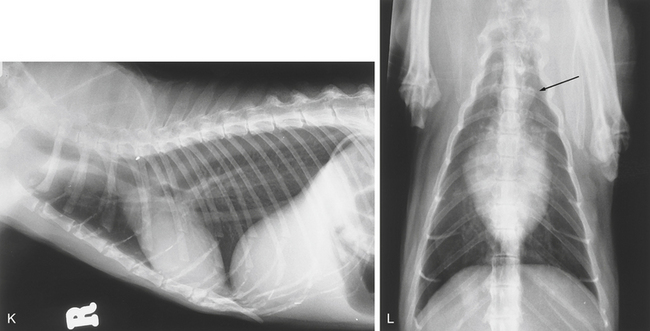

On the dorsoventral and ventrodorsal views, the angles between the diaphragm and the heart (cardiophrenic angles) and the diaphragm and the ribs (costophrenic angles) are well opened, and the cranial part of the diaphragm lies at approximately the level of the eighth to the tenth thoracic vertebrae. On the lateral view, projection of the dorsal curvature of the ribs unilaterally beyond the spine indicates that the animal was rotated axially when the radiograph was made. On dorsoventral and ventrodorsal views, the sternebrae and the spine should be superimposed on one another (Figure 3-6).

In the cat, the thorax appears more elongated and the cardiac outline is centrally located. In old cats, the aortic arch is often seen protruding cranial to the heart on the left side. The heart tilts more cranially in older cats (see Figure 3-6, D, I to L).

Ultrasonography

Sometimes an abdominal approach is used, called the subcostal approach. The transducer is located just caudal to the xiphisternum and angled cranially to locate the heart, using the liver as an acoustic window. This window is used to obtain a better Doppler angle of the aorta. This location is also useful for examining the diaphragm and caudal thorax. Rarely, the thoracic inlet may be used to image the cranial mediastinum and heart base—the suprasternal position.

1⁄30—or better,

1⁄30—or better,  1⁄60—of a second is desirable. Rare-earth screens reduce exposure times. At slower speeds, motion is not effectively excluded unless the animal is anesthetized and artificially ventilated. Motion causes blurring of intrathoracic structures and makes viewing of finer details impossible. Underexposure gives the impression of increased lung opacity. Films of obese patients are relatively underexposed, which may mimic pulmonary change. Overexposure blackens out normal vascular patterns and may mask pathologic changes. The use of a high-kilovoltage combined with low-milliamperage per-second technique gives a wider range of contrast than one of low kilovoltage. A good technique will barely outline the spinous processes of the cranial thoracic vertebrae on the lateral view.

1⁄60—of a second is desirable. Rare-earth screens reduce exposure times. At slower speeds, motion is not effectively excluded unless the animal is anesthetized and artificially ventilated. Motion causes blurring of intrathoracic structures and makes viewing of finer details impossible. Underexposure gives the impression of increased lung opacity. Films of obese patients are relatively underexposed, which may mimic pulmonary change. Overexposure blackens out normal vascular patterns and may mask pathologic changes. The use of a high-kilovoltage combined with low-milliamperage per-second technique gives a wider range of contrast than one of low kilovoltage. A good technique will barely outline the spinous processes of the cranial thoracic vertebrae on the lateral view.