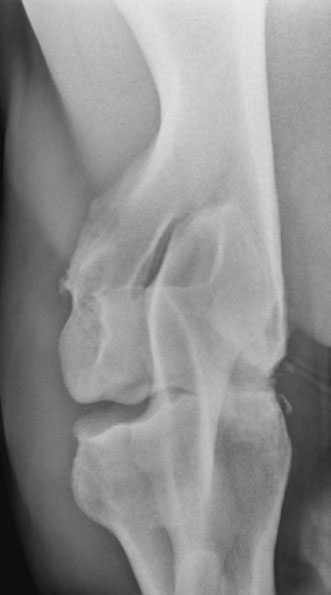

The elbow joint is composed of the articulation between the distal humerus and the proximal radius and ulna. The joint undergoes a large range of motion; however, due to the soft tissue attachments and bone articulation, joint movement is restricted to the sagittal plane.1,2 The humeral epicondyles articulate with the proximal aspect of the radius. Between the epicondyles is the olecranon fossa where the anconeal process from the olecranon interdigitates with the distal humerus. The olecranon tapers distally until it fuses (with maturity) with the caudal aspect of the radius. There is an intraosseus space that remains in the proximal portion of the antebrachium between the radius and ulna.1 The collateral ligaments are present medially and laterally to prevent movement in the frontal plane. The medial collateral ligament is divided into the long, superficial portion and short, deep portion. The medial collateral ligament is also covered by the transverse pectoral muscle making palpation of this ligament more difficult than the lateral collateral ligament.1 The muscles that aid in flexion of the joint consist of the biceps brachii and brachialis. The extensor muscles consist mostly of the triceps, but the tensor fasciae antebrachii and anconeus also have some importance for extending the elbow. The attachment of the triceps muscle group to the olecranon is the main source for extension of the elbow joint.1 Diagnosis of elbow disease is uncommon in the equine athlete, but can be due to developmental, traumatic, infectious, or non-septic inflammatory causes. Other causes of elbow lameness can be due to damage of the ligament and tendons in the region.3 The best approach to diagnosing elbow disease is with intra-articular blocks with 2% mepivicaine (See Chapter 13). The elbow joint can be anesthetized with the lateral, caudolateral, or caudal approaches. If the lateral approach is chosen and the needle inserted cranial to the lateral collateral ligament, verification of the needle within the joint should be confirmed as peri-articular deposition of the anesthetic has resulted in radial nerve paralysis.4 Treatment for radial nerve paralysis is described later in this chapter. The lameness rarely resolves completely following the block but can improve to greater than 80%.3 Flexion tests can be performed on the elbow by advancing the leg forward; this action simultaneously extends the shoulder joint.3,5 These flexion tests may be hard to interpret as some horses may resent this test and are negative for elbow disease. • Fractures of the ulna are relatively common in foals and adult horses. • Olecranon fractures typically result from a direct kick or falling injuries and so therefore are commonly associated with an open wound. • Diagnosis is typically with radiography or nuclear scintigraphy. • Many different fracture configurations are possible and most are amenable to repair or successful conservative therapy. Most horses with olecranon fractures have a history of a direct kick from another horse or are injuries sustained when falling. Horses typically present with an acute onset, severe lameness and, due to a lack of functional triceps, may have a dropped elbow appearance with an inability to extend the carpus.6 (Fig. 18.1) Clinical signs in horses with olecranon fractures may show a dropped elbow appearance, which is due to the lack of effective triceps function as this muscle attachment is to the fractured olecranon.6 This dropped elbow appearance occurs with displaced or unstable fractures. These horses may display swelling around or near the point of the elbow and may be sensitive to palpation in this area depending upon the degree and configuration of the fracture.3 Contrary to other horses with a dropped elbow appearance, such as those with complete humeral fractures or radial neuropathy, these horses may be able to bear weight on the limb (minimally displaced fractures). An open wound may also accompany these fractures, which may communicate with the elbow joint. Latero-medial and cranio-caudal radiographic projections are recommended to assess the fracture configuration and to determine if there is an articular component. Once the fracture is identified, it can be classified. There have been different grading schemes reported, but the authors use the one described below.7 • Type 1a: Fracture through the apophysis • Type 1b: Articular fracture through the apophysis propagating through the metaphysis of the olecranon to the articular margin • Type 2: Articular fracture through the olecranon ending into the elbow joint • Type 3: Fracture through the olecranon (non-articular) • Type 4: Comminuted fracture through the olecranon (articular or non-articular) • Type 5: Oblique fracture through the olecranon distally (minimal articular involvement). Radiography is the most common way to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 18.2). Nuclear scintigraphy may be useful in simple non-displaced fractures that are difficult to visualize radiographically. Computed tomography would be more useful for surgical planning; however, this is still not an easily accessible area to image in the adult horse due to the current gantry size in most available scanners. First aid to stabilize the fracture is indicated in cases where the horse is unable to bear weight on the limb. The leg should be bandaged and a full limb caudal splint from elbow to fetlock should be applied to lock the carpus in extension. Local wounds in open fractures should be clipped of hair and cleaned. Many of these horses become more comfortable with the splint applied. Displaced and articular fractures warrant internal fixation to restore the joint surface. Locking or Dynamic Compression Plates are typically used to repair these fractures.8–10 Articular fractures that are not displaced have the potential to be treated conservatively. Non-displaced and non-articular fractures are typically treated conservatively with rest, but should frequently be re-evaluated to ensure the fracture has not become displaced. A favorable prognosis can be achieved with most olecranon fractures. Non-displaced and non-articular fractures are the most amenable to conservative management. Type 5 and minimally displaced type 3 fractures can be treated conservatively successfully; whereas, other fracture configurations will typically require surgical treatment.11–14 • Radial fractures in horses are usually due to direct trauma to the area from a kick or a foal being stepped on. • There are reported cases of radial stress fractures albeit rare. • Diagnosis is best confirmed with radiography or in minimally displaced or incomplete fractures with nuclear scintigraphy. • If the fracture can be treated conservatively, the prognosis is good. • The prognosis for displaced radial fractures in adult horses is poor regardless of treatment. Horses typically present following a history of direct trauma or acute, severe lameness. The severity of lameness will depend upon the degree of displacement of the fracture.3,5,15 Complete, displaced fractures will result in a non-weight bearing lameness. A wound over the radius may be present and is commonly on the medial aspect of the limb due to decreased soft tissue coverage in this area. Clinical signs in horses with radial fractures will depend upon the degree of displacement and can range from a walking lameness to non-weight bearing. In horses with displaced fractures, attempts at weight bearing usually result in deviation of the limb and many will stand with their carpus and fetlock joints flexed and the toe dragging. Most horses will have significant swelling over the site of fracture. Affected horses may also have a visible deviation in the limb or palpable crepitance. Since there is minimal soft tissue covering over the radius many of these fractures have an associated wound medially. Non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures can be harder to diagnose as horses will be severely lame, but palpable swelling, crepitus, or a wound may not be present to point the examiner to the radius.15 Visual assessment of complete, displaced radial fractures is usually diagnostic; however, radiography is extremely helpful in determining the degree of comminution and the configuration of the fracture. Nuclear scintigraphy is helpful in cases of non-displaced or stress fractures of the radius.3 Standard latero-medial and cranio-caudal radiographic views are the minimum required to evaluate the fracture, but oblique views and stress views may provide valuable information. Stress fractures or incomplete radial fractures can be diagnosed with radiography or nuclear scintigraphy. Trauma to the radius can also result in sequestration or osteomyelitis, which can be suspected with radiography and/or scintigraphy.16 Computed tomography may be beneficial to fully characterize the fracture in foals with radial fractures, but the gantry size in most computed tomography scanners does not typically allow imaging of this area in the adult patient. Furthermore, since scanning requires general anesthesia substantial risk is encountered during anesthetic recovery unless the fracture is repaired with internal fixation. High-resolution ultrasound may be beneficial in locating breaks within the periosteum; however, the methods mentioned above are preferred. In horses with non-displaced or incomplete fractures, conservative therapy is recommended. This entails strict stall confinement and cross-ties to prevent the horse from laying down. Horses that have incomplete fractures that are not cross tied have the potential of causing further displacement or propagation of the fracture due to the stresses placed on the limb when attempting to stand. This stall confinement is recommended for 3–4 months prior to attempting short handwalks with periodic radiographic assessment of fracture healing.3 In cases that are not amenable to conservative management (displaced fractures), internal fixation with bone plates is required. Involvement of the fracture line into the elbow joint or a wound communicating with the joint must be ruled out to treat the horse conservatively.16 Sequestration requires removal of the fragment. Osteomyelitis requires long-term antimicrobial therapy. The prognosis of adult horses with complete radial fractures is poor. Although there have been successful attempts at internal fixation, oftentimes the internal fixation cannot withstand the forces applied to the radius. Although stronger locking plates are now available (5.5 broad), these can still be challenging fractures to internally stabilize due to secondary complications such as contralateral limb laminitis or implant infection. Conservatively treated horses with non-displaced fractures that strictly adhere to the stall confinement can have a good prognosis.17 Horses with sequestration without fracture have a good prognosis and those with osteomyelitis can have a good prognosis following surgical debridement and long-term antimicrobial therapy.16 • Septic arthritis of the elbow joint is almost always associated with a penetrating wound communicating with the elbow joint or recent history of joint injection. • Affected horses typically have a severe lameness that may result within 7–10 days following a traumatic wound to the area. • Definitive diagnosis is obtained with synovial fluid analysis. • Radiographs are useful in ruling out concurrent osseous damage. • In cases that are not treated aggressively, the long term prognosis is fair for soundness. Removal of inflammatory cells and fibrin can be accomplished with lavage of the elbow joint under general anesthesia. Through-and-through needle lavage can remove the source of infection and inflammatory mediators; however, advanced cases or those with gross contamination are better treated with arthroscopic lavage. Arthroscopic lavage not only provides a larger bore flush and facilitates removal of fibrin, but also provides a diagnostic view of the elbow joint. The horse should also be placed on systemic antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medications post-operatively.5,18 The prognosis will depend upon the degree of contamination and the chronicity of infection. Horses treated aggressively and early will have the best chance to prevent the onset of future osteoarthritis. Horses that develop osteoarthritis in the elbow joint are more difficult to manage than other joints.3 • Osteoarthritis in the elbow joint is an uncommon cause of lameness in adult horses. • Osteoarthritis is typically secondary to degenerative or traumatic causes. • Diagnosis is by intra-articular anesthesia of the elbow joint. • Treatments consist of intra-articular and systemic anti-inflammatory medications. • Management of osteoarthritis in the elbow joint is more difficult than other joints. Flexion or extension tests of the elbow may help localize the lameness to this region. Horses with effusion in the elbow joint will typically have a positive response to flexion. Interpretation of these tests may be difficult since some normal horses resent this leg manipulation. Comparison to the contralateral limb is recommended. Intra-articular anesthesia will improve the lameness in these cases.3,5 Therapies to treat osteoarthritis include: intra-articular corticosteroids, hyaluronan, polysulfated glycosaminoglycans or IRAP (see Chapter 23). Systemic joint therapies such as NSAIDs, hyaluronan, and polysulfated glycosaminoglycans can also be explored for treatment. Numerous oral supplements are available to reduce inflammation, but the authors typically only recommend those that have undergone testing such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, specifically brands such as Cosequin® ASU (Nutramax® Laboratories, Inc Edgewood, MD, USA) as they have been tested for their contents and studied in clinical trials. Significant disease modifying effects have not been demonstrated in horses although anectodal evidence of efficacy abounds. Topical medications such as 1% diclofenac sodium (Surpass® Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc. St. Joseph, MO, USA) has proven to have disease modifying effects in carpal joints with osteoarthritis and as such are frequently recommended to treat other joints with osteoarthritis.19 The prognosis for treating low-grade osteoarthritis is good with administration of the medications listed above; however, as this disease is progressive, these medications will ultimately become less effective over time. Prognosis is dependent upon the response to therapy, but cases with advanced radiographic changes will likely have a guarded prognosis for long term soundness. Overall osteoarthritis in this joint is more difficult to manage than in other joints.3 • Olecranon bursitis is also known as capped elbow, elbow hygroma, or shoe boil. • It is typically as a result of trauma to the olecranon. • The ‘bursa’ is not a normal anatomic structure, but forms from the trauma. • The prognosis is excellent for soundness, but may be difficult to resolve. Examination reveals a swelling over the point of the elbow that is not associated with the underlying bone (Fig. 18.4). The swelling is usually freely movable. Typically lameness is not present, even with infection. The non-septic swelling typically contains fluid, fibrous tissue or both.21 If the skin is damaged it is possible that there may be a wound and associated local infection. If therapy is chosen, injections with corticosteroids, orgotein, dysprosium-165 or atropine have been reported.20,21 Similarly injection of iodine or Lugol’s solution has been reported to be successful.3,21 Regardless of the product injected, most are unrewarding and/or require multiple injections to treat the condition. If there is an open wound, lavage with curettage of the ‘bursal’ lining can resolve the bursitis. The bursa may be surgically resected if the above methods fail to resolve the condition. These typically form with pressure being placed on the olecranon either by the heels of the shoe when the horse is recumbent or due to trauma, which is why they have been historically referred to as ‘shoe boils’. The resultant pressure leads to fluid accumulation underneath the skin. As the edema subsides, a fluid pocket remains. If the skin is irritated, an open wound may communicate with the ‘bursa’.21 • Collateral ligament injury typically occurs from trauma or a fall. • Lateral collateral ligament tears are more common than medial collateral tears and are relatively uncommon. • Diagnosis can be made using ultrasound. • Prognosis depends upon the degree of the tear with partial thickness. A favorable prognosis can be expected in partial tears and those with complete tears and corresponding subluxation of the elbow joint have a guarded prognosis for return to use. Horses will typically have a severe lameness and may have soft tissue swelling over the corresponding trauma. Abduction or adduction of the limb may provide a presumptive diagnosis; however without complete tearing the bone articulation between the humerus and the radius/ulna, the diagnosis may be difficult without imaging.3 Ultrasound is the diagnostic method of choice for collateral ligament injuries. Radiography can be beneficial in cases where the ligament is completely torn, there are avulsion fragments or secondary osteoarthritis within the elbow joint.22 Distraction views can be helpful in diagnosing the rupture (Fig. 18.5). Nuclear scintigraphy can be beneficial if ultrasound or radiographs fail to diagnose the condition due to the bone attachments of these ligaments to the lateral humeral epicondyle or the lateral radial tuberosity. Intra-articular analgesia may improve the lameness; however, if the tears are outside of the elbow joint, these may be negative. As there are no surgical procedures for treating these ligaments, healing is by second intention. Regenerative therapies such as bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells or platelet rich plasma may be beneficial in these cases.23–25 Recheck ultrasound and lameness examinations should be performed periodically. The horse should be kept under stall confinement for at least a few months depending upon the degree of damage and then can be gradually re-introduced to handwalking. The course of healing will depend upon the degree of damage, but can take upwards of six months to one year for complete healing. Rehabilitation depends on ultrasound appearance on recheck examinations.

Elbow and Shoulder

Anatomy

Ulnar/olecranon fractures

Recognition

History and presenting complaint

Physical examination

Special examination

Classifications

Diagnostic confirmation

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Prognosis

Radial fractures

Recognition

History and presenting complaint

Physical examination

Special examination

Diagnostic confirmation

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Prognosis

Septic elbow arthritis

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Prognosis

Osteoarthritis of the elbow joint

Recognition

Special examination

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Prognosis

Olecranon bursitis

Recognition

Physical examination

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Etiology and pathophysiology

Collateral ligament injury/luxation

Recognition

Physical examination

Special examination

Treatment and prognosis

Therapy

Elbow and Shoulder