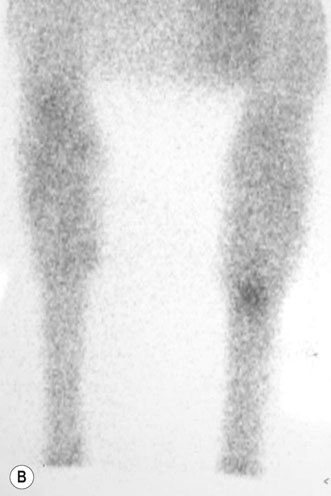

The discipline of dressage consists of the execution of different movements and transitions which are considered to be the constituents of basic equitation for all equestrian disciplines. ‘Dressage is considered the art of equestrian sport … It is the highest expression of horse training.’1 With adequate training, a horse will gain improved gymnastic skills enabling it to perform more sophisticated figures (Fig. 51.1). Dressage is a test of obedience, balance and suppleness. ‘The object of dressage is the harmonious development of the physique and ability of the horse. As a result it makes the horse calm, supple, loose and flexible but also confident, attentive and keen, thus achieving perfect understanding with his rider.’1 The goal is that the horse ‘gives the impression of doing of his own accord what is required of him. Confident and attentive, he submits generously to the control of his rider, remaining absolutely straight in any movement on a straight line and bending accordingly when moving on curved lines.’1 Dressage competitions are executed in a 60 m × 20 m rectangular arena, delimited by a low rail along which 12 lettered markers are placed symmetrically indicating where movements are to start or finish and where changes of pace or lead are to occur.1 During a dressage competition, the ability of horse and rider to perform imposed figures and transitions is judged (Fig. 51.2). In all competitions, the horse must enter the ring and then stand square at a halt (and the rider must salute). Basic dressage gaits are walk, trot, and canter. The international standard requires that: His walk is regular, free and unconstrained. His trot is free, supple, regular, sustained and active. His canter is united, light and cadenced. His quarters are never inactive or sluggish. He responds to the slightest indication of the rider and thereby gives life and spirit to all the rest of his body.1 Significant variability in judging has been demonstrated, even at the Olympic level, suggesting that judges encounter difficulties in objective scoring and scores do not always align with overall performance.2 Movements are judged on ‘freedom and regularity of the paces; the harmony, lightness and ease of movements; the lightness of the forehand and the engagement of the hind quarters, originating in a lively impulsion; the acceptance of the bridle, with submissiveness throughout and without any tenseness or resistance.’1 Rhythm, energy, balance, forward movement, and elasticity of the horse are qualities that are highly sought. Figures should be executed in an easy and fluent way, without abruptness or obvious tension between the horse and rider. The emphasis, at all times, is that the horse should be perceived as willing to perform the exercises and make difficult exercises appear easy. In the FEI guidelines, it is also stated that the aim should always be to demonstrate ‘the harmony and willingness to perform, not force horses to show tricks.’1 Internationally the sport is known as the Concours de Dressage International (CDI).1,3 International dressage competitions are ranked by the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) as increasing in difficulty from one (CDI*) through three-star (CDI***). The abbreviation CDIO designates an Official (Officiel) CDI to which national federations are invited to send selected representative teams and individuals, such as for the Olympic Summer Games or World Equestrian Games.3 Levels of increasing difficulty of FEI dressage competition include Prix St. Georges, Intermediate I, Intermediate II, Grand Prix, and Grand Prix Special.1 Freestyle is also an FEI-sanctioned competition held at either the Intermediate or Grand Prix level. Competitions sanctioned by the United States Equestrian Federation (USEF) are progressively ranked as Training, First Level, Second Level, Third Level, Fourth Level, and Fifth Level (equivalent to international competition).4 The standard for FEI championships and the Olympic Games consists of Grand Prix, Grand Prix Special, and Grand Prix Freestyle (Kur) tests. Horses have been used as mounts for the military since early history. The earliest work on training military horses for obedience and maneuverability was written by Xenophon, a Greek military commander. Through history, as the art of warfare evolved, lighter horses such as Arabians were bred to the heavy draught warhorses to improve their stamina and versatility. With these evolutions, dressage techniques became more sophisticated. During the Renaissance, European aristocrats participated in equestrian pageants to demonstrate the military skills of their mounts. Several prominent riding schools were later founded to perpetuate the art of dressage training (e.g. the Imperial Spanish Riding School of Vienna, and the French Cadre Noir). In 1912, dressage was introduced as an Olympic sport. At the time, only commissioned military officers were eligible to compete. The competition included tests of obedience and maneuverability that would later become known as dressage. In 1956, when many military cavalries were dismantled, the discipline was opened to civilians. Although women were not allowed to compete before 1964, over 80% of equestrian competitors today are female, with a substantial number competing into advanced age.5 At upper levels of competition, dressage horses are almost exclusively Warmbloods. In the origin of the Warmblood breeds, Arabian and Thoroughbred horses were bred to sturdier working breeds to lighten their conformation and improve their movement and stamina. The German Warmbloods are largely predominant at the upper levels, with five Germans studbooks represented in the World Breeding Federation for Sport Horses/FEI ranking of the top 10 breeds in dressage.6 Of the 20 best internationally ranked individual horses, 15 are registered in German studbooks.6 Gait and conformation analysis data on three-year-old dressage horses (n = 142) has shown German Warmbloods (Hanoverians [n = 31], Westphalians [n = 16], and Oldenburgers [n = 6]) to be biomechanically superior to both Selle Francais (n = 61) and purebred Spanish horses (n = 28) for use in competitive FEI dressage.7 The superior stature and conformation of the German horses resulted in a longer stride length and decreased stride frequency. ‘The German horses had gait characteristics more adapted to dressage competition,’ the authors concluded.7 Studbooks operate a strict selection of their breeding mares and stallions to ensure a constant improvement of their dressage horses. Selection is based on conformation, performance, health, and offspring performance. The horses are requested to regularly participate in scheduled selection competitions. Veterinary examinations are compulsory to ensure the absence of heritable defects. To improve selection of the best breeders and maintain the quality of the horses produced with the increase in the trade of foreign semen, the results from performance tests and competitions of young horses are now used by major European Warmblood horse breeding associations for genetic evaluations.8 Selection according to conformation criteria is often more empirical and has shown a fairly low correlation with future performance.9 However, it is of importance to the veterinary profession as it correlates with injury resistance.10 Gait characteristics provide an early criterion for breeding in dressage breeding programs, but their implementation in practice is difficult as it requires the use of gait analysis techniques.11 Behavior-related traits have also been examined as part of performance evaluations and may be partially predicted by personality traits analyzed earlier in life.12 The relationship between performance and particular traits such as ridden test scores has been scientifically studied. Specially designed young horse performance tests, including stallion tests, showed high heritabilities as well as high genetic correlations between analyzed traits and later competition results, thus proving their usefulness in predictability of dressage performance.13 These performance test scores represent the main selection criteria in most modern breeding schemes of sport horses.14 Dressage horses may not compete under FEI rules until they are at least six years old.1,3 Horses competing in the Olympic Games or World Equestrian Games must be at least seven years old.3 Dressage horses may not compete in Grand Prix, Grand Prix Special, or Grand Prix Freestyle until they are at least seven years old.1,3 In competitions, stallions usually perform better than geldings. Dressage horses have their most productive years at the upper levels at approximately 8–12 years of age. In studies correlating performance with age, it has been demonstrated that dressage horses reach peak performance around the age of 10 years old.15 Dressage is highly dependent on the human–equine interaction and mutual collaboration to compete successfully. The horse’s individual qualities are intimately tied to rider’s experience and equitation. At the elite level, dressage still reflects the rigorous demands of historical military cavalry training. Precision, obedience, stamina, versatility, and the competitive mindset of both rider and horse are unquestionable advantages to compete successfully. Mental skills of the rider, for instance, have been shown to have a positive effect on competitive dressage performance.16 Poor conformation plays a significant role in many unsoundnesses. For example, post-legged or straight hind leg conformation can predispose a dressage horse to hock or stifle lameness, as will sickle hocks or the cow-hocked conformation which may be more common in some breeds. Due to the stresses caused by the bending and the excessive hindlimb reaching required in dressage (‘impulsion’), hock pain and bone spavin are common maladies of dressage horses. See Figures 51.3A and B. A recent survey of 11 363 registered members of British Dressage identified risk factors for lameness in dressage horses.17 Owners reported in the 2005 survey that 33% of their dressage horses had been lame at some time during their career and 24% had been lame at some time in the last two years. Factors associated with occurrence of lameness in the previous two years included: age, height, indoor arenas, horse walkers, lunging, back soreness, arenas which became deeper when wet, and sand-based arenas. Various types of arena surfaces may be associated with lameness problems. In the United Kingdom, survey results of dressage competitors and trainers indicate that wax-coated and mixed sand/rubber surfaces were less detrimental to soundness.18 Woodchip surfaces were most often associated with lameness followed by sand alone, sand/PVC mixtures, and grass surfaces. Woodchips were associated with slipping and sand was associated with tripping during dressage exercises. The ideal surface was felt to have a limestone base; crushed concrete was to be avoided as a base material. Forelimb problems in dressage horses may not be as common as hindlimb problems, but can still be of significance to individual horses. Forelimb problems can be caused or exacerbated by poor conformation. In one recent survey of foot conformation in 23 116 Dutch Warmblood horses (registered with the Royal Dutch Warmblood Studbook, KWPN), it was determined that competitive life was shorter for jumpers than for dressage horses.19 ‘Uneven feet’ tended to shorten the competitive life of KWPN dressage horses and was associated significantly as a risk factor for lameness in elite jumpers.19 Furthermore, foot conformation was found in 33 459 dressage horses and 30 474 show jumpers to be prevalent in 4.5–8% of KWPN horses annually from 1990–2002.20 Improper hoof balance is not a rare problem and is best corrected with the farrier and veterinarian working together to achieve proper medial-to-lateral and left-to-right hoof balance. Corrective shoeing for poor forelimb foot conformation may be performed in dressage horses, but with some concern about shoe loss from overreaching from behind during extended trotting or cantering exercise. Forelimb lameness in dressage horses may also be related to their lengthy extension at the upper levels of competition (Fig. 51.4). Fetlock synovitis or arthritis is seen secondary to extended movements at upper levels, especially in former Thoroughbred racehorses converted to use as dressage horses. Suspensory branch injuries can be common and may become chronic recurring causes of lost training time. Diagnosis is by palpation, flexion responses, local anesthesia to localize the lesion, and radiography and/or ultrasonography. Intra-articular or peri-ligamentous corticosteroid and/or hyaluronic acid injections are often used in the acute phases of distal forelimb injury to the fetlock, pastern, and coffin joints or the branches of the suspensory ligament. However, chronic corticosteroid use may be associated with iatrogenic calcification of ligament and joint capsule and counterproductive appearance of enthesiophytes (formation of a ‘steroid arthropathy’). Progressive loading such as handwalking followed by walking with a rider on the back can be helpful eventually in the recovery from these injuries, but excessive turning such as may be done on a mechanical horse walker is to be avoided during recuperation. Proximal suspensory ligament and check (accessory) ligament injuries require lengthy periods of recuperation. Local anesthesia of the joints and regions below the high metacarpus do not result in improvement. A positive response to a high palmar anesthetic block or to local anesthesia of the region around the head of the suspensory ligament is diagnostic. Intra-articular anesthesia of the middle carpal joint will also often result in improvement due to diffusion of local anesthetic out of the joint capsule and into the head of the suspensory ligament.21 Ultrasound examination of the high suspensory and check ligament area may confirm the diagnosis by documentation of localized hemorrhage, edema, and fiber disruption. In horses which block out in this region but in which the high suspensory ligament does not reveal obvious ultrasonographic changes, a bone scan is indicated.21 Proximal palmar stress injuries or stress fractures might be apparent on scintigraphic examination (as illustrated for plantar lesions in Figure 51.3). Follow-up scintigraphy might assist effectively in monitoring recovery, which may require six months or more for complete healing and soundness in the forelimb. Radiographs may confirm a classic ‘gull-wing’ appearance to the stress fracture which will manifest cortical and intramedullary calcification (callus formation) as the stress fracture begins to heal.21 Osteoarthritis of the medial aspect of the distal tarsal joints (‘bone spavin’) is common in dressage horses due to the excessive flexion and extension required for adequate impulsion to be competitive. Intra-articular corticosteroid administration is common for treatment of distal tarsal osteoarthritis. Repeated administration may be required every few months to maintain competitive soundness. In approximately 25% of horses, the distal intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joints intercommunicate, so anesthetic or corticosteroid injected into the easier site, the tarsometatarsal joint, will diffuse into the distal intertarsal joint and will require fewer injection sites to diagnose or medicate the horse.22 Eventual fusion of the distal intertarsal and/or tarsometatarsal joints may result in soundness without further medication. For horses which tend to toe out behind (‘cow-hocked’), squaring the toes and application of short lateral trailers on the shoes may assist in some correction of the conformation and limb flight. That correction may lead to less medial tarsal pain since straightening the breakover path minimizes undue stress on the dorsomedial aspect of the distal tarsal joints. Conversely, and seemingly contradictorily, in some horses with tarsal pain already shod with lateral trailers, removing the shoes with a lateral trailer may assist in recovery if the trailers are causing a sudden grip and stop of those feet, jolting the limbs acutely with each stride and exacerbating tarsal pain.

Veterinary aspects of training dressage horses

Definitions and background

A brief history of dressage

Demographics

Common diseases and conditions

Skeletal

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterinary aspects of training dressage horses