Chapter 4 Behavioral Clues for Detection of Illness in Wild Animals: Models in Camelids and Elephants

As often noted, wild animals may be in an advanced state of disease before clinical signs are evident. Wild animals are not immune to pain or discomfort, but they do attempt to mask overt signs that would reveal their physical condition. Wild animal veterinarians should make every effort to diagnose disease at its earliest stages. Therapy may be useless unless it is initiated early in the course of a disease.

This chapter focuses on camelids and elephants in discussing normal and altered behavior in relation to the health and well-being of the animal.4,5 The influence of behavior on the health of animals is not a new concept, but it has become an important facet of veterinary medical education only during the last two decades. Several disciplines use behavior as a basis for study, including psychology, ethology, sociobiology, and animal behavior. Numerous contemporary authors discuss basic animal behavior and clinically abnormal behavior.1,10–13,16,25

Acquiring observational skills is important for the following reasons:

A veterinarian must first understand normal behavior to be able to detect abnormal behavior. Behaviors to be included are methods of offense and defense; communication (vocalization, body language, facial expression), social behavior, interaction with other animals, hierarchic status, locomotion, food intake, defecation/urination, scent marking, recumbency, getting up and down, reproductive behavior (courting, copulation), and stress.8,14,16,23,27

CAMELIDS

Normal Behavior

Offense and Defense

Offense and defense weapons used by camelids include kicking, charging, chest butting, biting, and spewing stomach contents (spitting) onto other camelids or people (Figures 4-1 and 4-2). Veterinarians and animal handlers must be aware of any abnormal behavior that may develop in hand-raised camelid neonates. Camelid neonates (cria in South American camelids [SACs], Spanish term for “baby animal,” and calf in Old World camelids [OWCs]) that are bottle-fed and kept without social intercourse with other camelids may become imprinted on people. The resulting abnormal behavioral characteristics are more critical in male camelids but may also occur in females. When the hand-raised male reaches sexual maturity, he may begin to treat humans as he would another male camelid. He will charge and chest-butt a person, who will likely be knocked down and then bitten. When male camelids fight other male camelids, they may bite each other on the legs, neck, or more seriously the scrotum, castrating the victim.

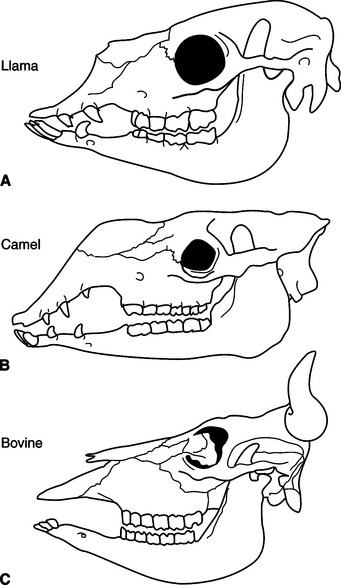

Male camelids have formidable canine teeth and are capable of inflicting serious or fatal injury (Figure 4-3). OWCs have been known to grasp a child by the head and shake it, often breaking the neck and crushing the skull.

Communication

Vocalization.

Although SACs are not highly vocal, they do have a repertoire of sounds. Alpacas are generally more vocal than llamas. The most common sound has been described as humming (bleating). The pitch and tone of the humming are significant in SAC communication. Franklin7 describes the “contact hum” as an auditory contact between herd members and especially between a mother and her cria. “Status humming” is a deeper tone that communicates contentedness, tension, discomfort, pain, or relief. The “interrogative hum” is higher pitched and has an inflection at the end. Other variations in intonation are described as a “separation hum” or a “distress hum.”

Body Language.

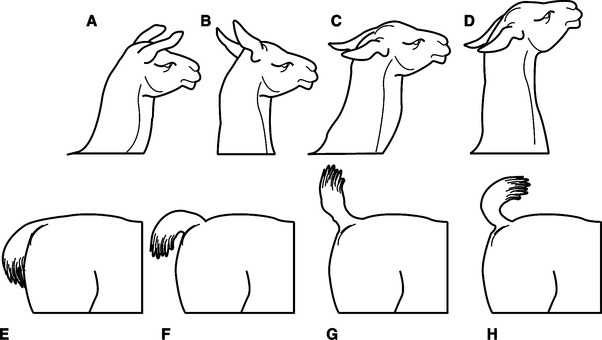

Body language, including ear and tail position, is a sure indicator of the mental state of a SAC. Various degrees of aggression are communicated between herd mates by ear, head, and tail positions, usually displayed in concert (Figure 4-4). The ears of a contented, nonaroused SAC are in a vertical position and turned forward. In the alert animal the ears are cocked forward; relaxed SACs may allow the ears to lie horizontal to the rear (Figure 4-5). This is a normal position and should not be considered aggression because other signs of aggression are absent. In some individuals the ears may appear to spread sideways from the top of the head. This ear position may be used when listening to activity behind them or just for relaxation. Asymmetric ear positions may also be seen. Ear and tail position may be in a continual state of flux, especially when animals are fed and if feeding stations lack adequate space for all herd members.

Mild to moderate aggression is signaled by the head held horizontal, with the ears positioned above the horizontal. As aggression increases, the ears are below the horizontal and may be flattened against the neck. Intense aggression is exhibited by the nose being pointed in the air and the ears flattened against the neck.

Submissiveness in the llama, guanaco, and alpaca is indicated by curving the tail forward over the back, with the head and neck held low, the ears in a normal to above-horizontal position, and the front limbs slightly bent (Figure 4-6). This behavior is frequently seen in SACs that become imprinted on humans. The submissive crouch of a vicuña is with the tail curved forward, but with the head curved back over the body.

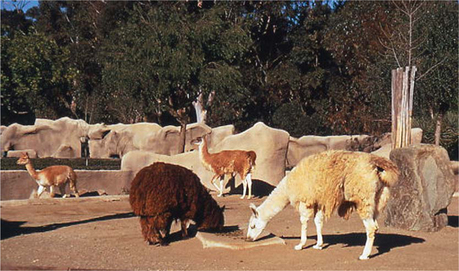

Social Behavior

All four species of SACs are social animals (Figure 4-7). Alpacas are generally more flock or herd oriented than llamas. Alpacas are also shyer, more easily frightened, and less curious than llamas. Wild SACs (guanacos and vicuñas) live in social groups.

Defecation and Urination

South American camelids normally urinate and defecate at communal dung piles (Figure 4-8). The ritual begins when first arising in the morning at daybreak. This may be the only time that urine samples and fresh fecal samples may be collected. The dung pile is a social gathering site. Camels defecate indiscriminately. Camel fecal pellets are so dry that they may be used for fuel immediately on discharge.

Grooming and Water Behaviors

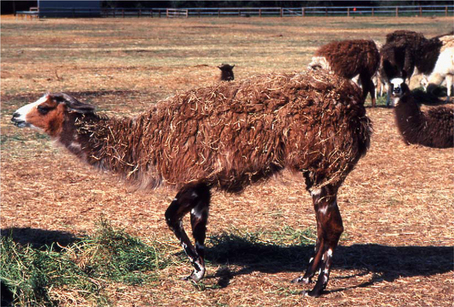

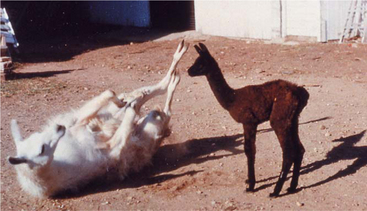

Rolling or dust bathing is one form of grooming in SACs (Figure 4-9). This behavior is so innate that pack llamas with full packs have been seen to lie down and attempt to roll. It may be similar to scratching one’s back. In addition to dusting, grooming involves other behaviors, such as scratching with a hind foot on the bottom of the abdomen, front limb, or head and neck; rubbing against fence posts, fencing, barns, or trees; and chewing at accessible points on the body or limbs. These behaviors do not necessarily signify a skin condition; it is often a simple itch.

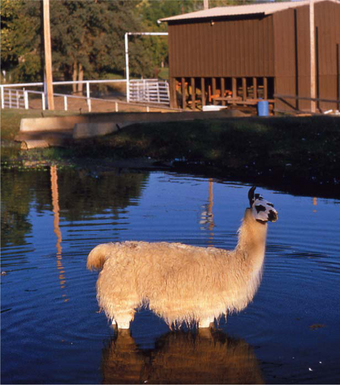

Alpacas like to play in water. If water is provided in tubs, buckets, or tanks, they will joyously splash. Both llamas and alpacas seek out water during hot weather (Figure 4-10). If a pond or large water tank is available, they may stand in the water up to their abdomen. Both species are capable of swimming but do so only when forced; however, they will stand or lie down in shallow ponds or streams to cool themselves. Heavy fiber normally covers the legs of alpacas down to the fetlocks. In hot weather they may stand in water so long that the leg fiber becomes macerated and sheds, leaving a blocked-haircut appearance on the upper leg.

Locomotion

Juvenile SACs often engage in play behavior; tussling with one another and, especially at twilight, engaging in a fifth gait, a stiff-legged bouncing called stotting or pronking. Occasionally, young adults will also join in the activity, particularly females trying to attract the attention of males.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree