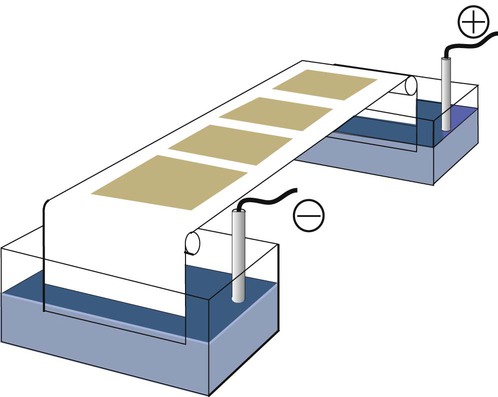

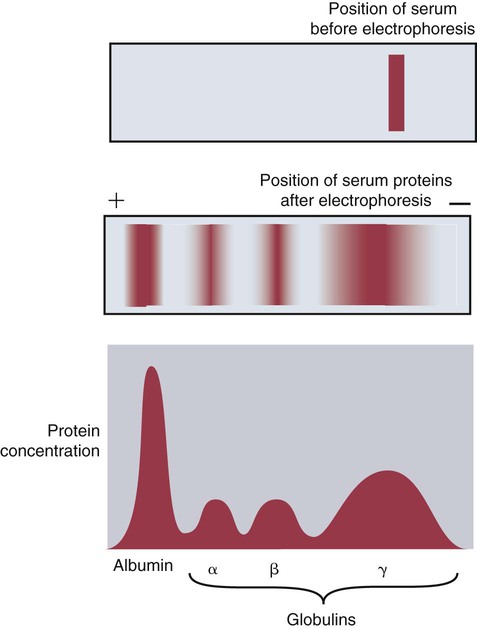

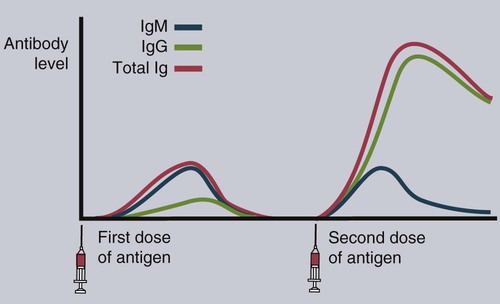

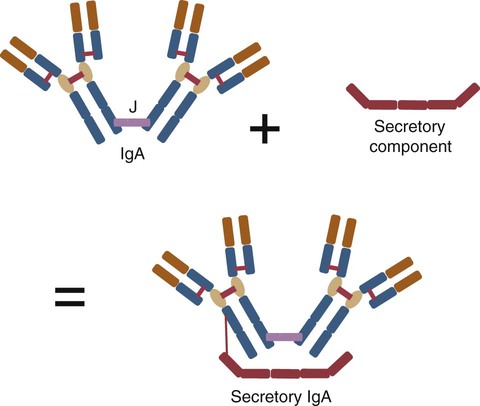

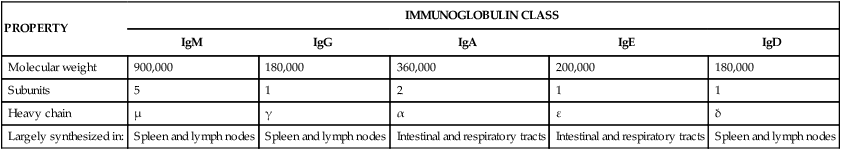

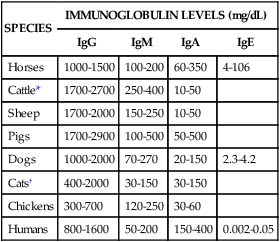

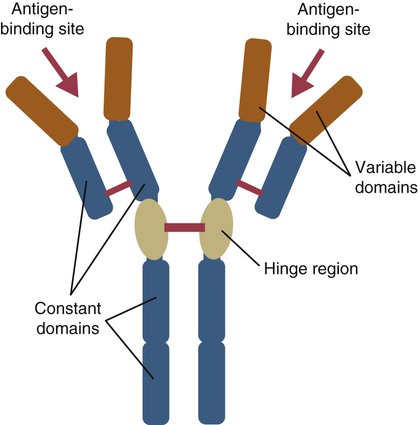

• Mammals make five classes of immunoglobulins: immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, IgA, IgE, and IgD. All originate as B cell antigen receptors (BCRs) shed into body fluids. • IgG is the predominant immunoglobulin in serum and is mainly responsible for systemic defense. • IgM is a very large immunoglobulin mainly produced during a primary immune response. • IgA is the immunoglobulin produced on body surfaces. It is responsible for the defense of the intestinal and respiratory tracts. • IgE is found in very small quantities in serum and is responsible for immunity to parasitic worms and for allergies. • IgD is found on the surface of immature lymphocytes. Its function is unknown. The properties of the B cell antigen receptors (BCRs) are discussed in Chapter 15. These receptors are, however, not restricted to the B cell surface. Once a B cell response is triggered, its antigen receptors are produced in huge amounts and shed into the surrounding fluid, where they act as antibodies. These antibodies bind to foreign antigens and mark them for destruction or elimination. Antibodies are found in many body fluids but are present in highest concentrations and are most easily obtained from blood serum. Antibodies have to defend an animal against a variety of microbes, including bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. They also must act in several different environments, for example, in blood and milk and on body surfaces. It is not surprising, therefore, that multiple immunoglobulin classes exist. Each class is optimized for action in a specific environment; for instance, IgA protects body surfaces. Immunoglobulins may also be optimized for activity against a specific group of pathogens. For example, IgE is important in the defense against parasitic worms. Antibody molecules are glycoproteins called immunoglobulins (abbreviated as Ig). The term immunoglobulin is used to describe all soluble BCRs. There are five different classes (or isotypes) of immunoglobulins, which differ in their use of heavy chains. The class found in highest concentrations in serum is called immunoglobulin G (abbreviated IgG). The class with the second highest serum concentration (in most mammals) is immunoglobulin M (IgM). The third highest concentration in most mammals is immunoglobulin A (IgA). IgA is, however, the predominant immunoglobulin in secretions such as saliva, milk, and intestinal fluid. Immunoglobulin D (IgD) is primarily a BCR and is rarely encountered in body fluids. Immunoglobulin E (IgE) is found in very low concentrations in serum and mediates allergic reactions. The characteristics of each of these classes are shown in Table 16-1. Table 16-1 Major Immunoglobulin Classes in the Domestic Mammals When serum is subjected to electrophoresis, its proteins separate into four major fractions (Figure 16-1). The most negatively charged fraction consists of a single homogeneous protein called serum albumin. The other three major fractions contain protein mixtures classified as α, β, and γ globulins, according to their electrophoretic mobility (Figure 16-2). Most immunoglobulins are found in the γ globulins, although IgM migrates with the β globulins. IgG is produced by plasma cells in the spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow. It is the immunoglobulin found in highest concentration in the blood (Table 16-2) and plays the major role in antibody-mediated defenses. It has a molecular weight of about 180 kDa and a typical BCR structure with two identical light chains and two identical γ heavy chains (Figure 16-3). Its light chains may be of the κ or λ type. Because it is the smallest of the immunoglobulin molecules, IgG can escape from blood vessels more easily than can the others. This is especially important in inflammation, in which increased vascular permeability allows IgG to participate in the defense of tissues and body surfaces. IgG binds to specific antigens such as those found on bacterial surfaces. Binding of these antibody molecules to bacterial surfaces can cause clumping (agglutination) and opsonization. IgG antibodies activate the classical complement pathway only when sufficient molecules have clustered in a correct configuration on the antigenic surface (Chapter 7). Table 16-2 Serum Immunoglobulin Levels in the Domestic Animals and Human *Cattle show significant seasonal differences in serum immunoglobulin levels. †Immunoglobulin levels in pathogen-free cats are about half those in pet cats. IgM is also produced by plasma cells in the secondary lymphoid organs. It occurs in the second highest concentration after IgG in most mammalian serum. When attached to the B cell surface and acting as a BCR, IgM is a 180-kDa immunoglobulin monomer. However, the secreted form of IgM consists of five (occasionally six) 180-kDa units linked by disulfide bonds in a circular fashion. Its total molecular weight is 900 kDa (Figure 16-4). A small polypeptide called the J chain (15 kDa) joins two of the units to complete the circle. Each IgM monomer is of conventional immunoglobulin structure and consists of two κ or λ light chains and two µ heavy chains; µ chains differ from γ chains in that they have an additional, fourth constant domain (CH4), as well as an additional 20-amino acid segment on their C-terminus but have no hinge region. The complement activation site on IgM is located on the CH4 domain. IgM is the major immunoglobulin produced during a primary immune response (Figure 16-5). It is also produced in secondary responses, but this tends to be masked by the predominance of IgG. Although produced in small amounts, IgM is more efficient (on a molar basis) than IgG at complement activation, opsonization, neutralization of viruses, and agglutination. Because of their very large size, IgM molecules rarely enter tissue fluids even at sites of acute inflammation. IgA is secreted by plasma cells located under body surfaces. Thus it is made in the walls of the intestine, respiratory tract, urinary system, skin, and mammary gland. Its serum concentration in most mammals is usually lower than that of IgM. IgA monomers have a molecular weight of 150 kDa, but they are normally secreted as dimers. Each IgA monomer consists of two light chains and two α heavy chains containing three constant domains. In dimeric IgA, two molecules are joined by a J chain (Figure 16-6). Higher polymers of IgA are occasionally found in serum. IgA produced in body surfaces is transported through epithelial cells into external secretions. Thus most of the IgA made in the intestinal wall is carried into the intestinal fluid. This IgA is transported through intestinal epithelial cells bound to the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) or secretory component (Figure 22-13). Secretory component binds IgA dimers to form a complex molecule called secretory IgA (SIgA). It protects the IgA from digestion by intestinal proteases. Secretory IgA is the major immunoglobulin in the external secretions of nonruminants. As such, it is of critical importance in protecting the intestinal, respiratory, and urogenital tracts, the mammary gland, and the eyes against microbial invasion. IgA does not activate the classical complement pathway, nor can it act as an opsonin. It can, however, agglutinate particulate antigens and neutralize viruses. IgA prevents the adherence of invading microbes to body surfaces. Because of its importance, IgA is examined in more detail in Chapter 22.

Antibodies

Soluble Antigen Receptors

Immunoglobulins

PROPERTY

IMMUNOGLOBULIN CLASS

IgM

IgG

IgA

IgE

IgD

Molecular weight

900,000

180,000

360,000

200,000

180,000

Subunits

5

1

2

1

1

Heavy chain

µ

γ

α

ε

δ

Largely synthesized in:

Spleen and lymph nodes

Spleen and lymph nodes

Intestinal and respiratory tracts

Intestinal and respiratory tracts

Spleen and lymph nodes

Immunoglobulin Classes

Immunoglobulin G

SPECIES

IMMUNOGLOBULIN LEVELS (mg/dL)

IgG

IgM

IgA

IgE

Horses

1000-1500

100-200

60-350

4-106

Cattle*

1700-2700

250-400

10-50

Sheep

1700-2000

150-250

10-50

Pigs

1700-2900

100-500

50-500

Dogs

1000-2000

70-270

20-150

2.3-4.2

Cats†

400-2000

30-150

30-150

Chickens

300-700

120-250

30-60

Humans

800-1600

50-200

150-400

0.002-0.05

Immunoglobulin M

Immunoglobulin A

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree