Immunodeficiencies in humans have various physiologic and pathologic causes (Box 99-1). Genetically inherited deficiencies cause an increased susceptibility to many pathogens, which vary according to the type and penetrance of the defect.364 Age is one determinant; for example, fetuses, neonates, and young children have underdeveloped immune systems. Similarly, frail older adults, especially those in nursing homes or hospitals, have apparent increased risks of developing infections. In addition to having physical disabilities and altered resistance, they may also be cognitively impaired.364 Invasive fungal infections are an increasing problem in organ transplant recipients and older adults.284 A closed institutional environment favors more intense exposure to microorganisms because of limited ventilation and frequent close contact with other individuals. Approximately 1,039,000 to 1,185,000 humans in the United States are infected with HIV, and approximately 25% do not know they are infected.103 It is estimated that approximately 10 million individuals, almost 4% of the population, in the United States are immunocompromised; patients with cancer (approximately 8.5 million), recipients of organ transplants (184,000 solid-organ transplants in the 1990s), and individuals with HIV infection (1,106,400 persons).99,289 There is a significant number of individuals who take immunosuppressive drugs for rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease who are not included in these numbers. There are approximately 25,000 splenectomies performed each year in the United States500 in addition to the thousands of functionally hyposplenic patients, all of whom are considered at increased risk because of their immunocompromised status. In addition, there are many individuals with other underlying conditions that have less pronounced but still significant effects on the immune system, such as diabetes, renal disease, and cirrhosis. Further, pregnant women also have varying degrees of immunodeficiency; estimates are that 2% of the population of the United States is pregnant at any given time.487,537 Up to 50% of the immunocompromised population own companion animals,121,483 as is typical for the population at large.572 Approximately 171 million pet dogs and cats live in the United States.254 The estimated prevalence of companion animals in all U.S. households is 62%, 45.6% of which are dogs, 38.2% cats, 5.3% birds, and 3.9% horses.12 Although more households have dogs, the total number of cats is greater than that of dogs. The psychological benefits that these companion animals provide are great, and the risk for acquiring infections from animals is low. Nevertheless, taking certain precautions while handling and caring for pets reduces any inherent risks. The information in this chapter emphasizes zoonoses that are more commonly identified in immunocompromised individuals. However, because zoonoses can develop in immunocompetent humans, many of the principles and practices can pertain to anyone with pets. In the strict sense, zoonoses are defined as infectious diseases naturally transmitted from living animals to humans.251 Based on the animal reservoir hosts, zoonoses can be synanthropic with an urban or domestic animal cycle, or exoanthropic with a feral or wild animal cycle. Immunocompromised humans who own pets are at greater risk of contracting directly transmitted zoonotic infections than those without pets (Box 99-2). Inhalation or ingestion of infectious body secretions and excretions is the common means by which many zoonotic infections may be transmitted directly. However, transmission can occur percutaneously through contamination of preexisting skin wounds or by bites or scratches. Spread can also occur after contact of mucosae with fomites such as contaminated utensils or food or water. Arthropod-borne transmission also occurs in some infections of dogs and cats, and zoonotic infections occur when these vectors feed on cohabitating humans. In some cases, dogs and cats can bring vectors that are already infected with an organism closer to humans. Once infected, humans rarely transmit zoonoses to other humans. Some zoonotic infections can be extremely severe or highly fatal. Sapronoses are infections of humans and animals that are maintained in nature by replication of the organism in soil or water, on vegetation, or in the decay of dead animals or animal excreta. With these zoonoses, both humans and animals acquire infections in a similar manner but independently of each other. Sapronoses were previously but inaccurately called “saprozoonoses,” but they are not truly acquired by humans from living animals (see Box 99-2). Instead, when animals get these infections, they act as sentinels for the risk of human infection in the area of occurrence. Anthroponoses are infections in which the source, replication, and primary means of transmission occur in humans. Some of these infections can affect animals such as dogs and cats (see Box 99-2). The importance of zoonotic diseases has been highlighted by the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic in humans. In fact, the appearance of unusual zoonotic infections in humans was one reason that AIDS was first recognized. The increasing incidence of zoonotic infections in immunosuppressed humans makes it imperative that veterinarians know the most current information about these diseases. Humans with AIDS who have questions about their pets most frequently consult physicians, nurses, and community health personnel, many of whom give conflicting advice, whereas very few consult their veterinarians.14,120,120 Surveys have shown that more than 60% to 90% of humans infected with HIV have been advised by human health professionals to give up their pets, whereas only 5% have followed this advice.57,481 Compared with veterinarians, most physicians are not well trained in zoonoses, and their advice, when given, is often for patients to give up their pets.14,188 Veterinarians can be the best source of information about the relative risk of pet ownership and precautionary measures for immunocompromised humans to take so that they can keep their pets.275 In spite of this, few veterinarians take an active role in educating their immunodeficient pet owners.14,481 The latest guidelines from the U.S. Public Health Service and the Infectious Disease Society of America recommend that rather than give up their pets, immunocompromised humans can take simple precautions to prevent infection.16,19,279,356 At first glance, the risk of acquiring animal infections can seem to dominate the medical literature and media reports, but only a relatively small fraction of infections in humans can actually be attributed to pet contact. Humans with immunosuppression are at increased risk for acquiring all types of infections, including zoonoses. However, humans are more likely to acquire infections from other humans than from animals. Furthermore, some of the highly publicized zoonoses in AIDS patients, such as toxoplasmosis, are caused by reactivation of a previously acquired infection and are not related to pet exposure. The Internet is potentially a tremendous resource for information on zoonotic diseases. Box 99-3 lists important websites for health care workers associated with immunocompromised individuals. Veterinarians and animal health workers may be at greater risk for acquiring zoonoses.34 Humans who work in allied professions involving animal products for food or fiber are also at risk, as are those who work on farms or in zoological gardens where animal contact is allowed. In the zoological gardens, almost all exposures involved domestic herbivores and infections with feces-borne pathogens such as Campylobacter, Giardia, Salmonella, and Cryptosporidium spp.49 In a study of veterinarians in South Africa, those in farm practice were three times more likely to have contracted a zoonotic disease than those working in other veterinary fields.219 Urban zoonoses can be caused by members of the genera Bartonella, Coxiella, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia. These diseases have synanthropic cycles in which vertebrate hosts and their associated arthropod vectors can survive in metropolitan regions. Increasing population densities, encroachment on sylvan cycles of infection, increased homelessness, greater numbers of immunosuppressed people, and poor hygiene in economically disadvantaged inner-city environments are all responsible for this development.117 In one study in northern Florida, the prevalence of zoonotic infections such as toxoplasmosis or bartonellosis among feral and pet cats was equivocal,343 suggesting that feral cats pose no greater risk to humans than owned pet cats. In another report, feral and pet cats from one county in rural North Carolina had similar prevalence rates of infection with Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia spp., and Toxocara cati. However, a statistically higher seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae and Toxoplasma gondii antibodies was found in feral cats,409 presumably because of greater exposure to outdoor vectors of these diseases. These studies seem to refute the common conception that feral cats have poor health and are poor choices as pets, especially for immunocompromised humans. A more important criterion appears to be whether the potential pet frequents outdoor environments. Veterinarians have an inherent responsibility to advise pet owners on their risk of contracting zoonotic diseases from their animals. An excellent review of this subject has been published.32 From ethical perspectives, veterinarians have a duty to exercise care in protecting clients from acquiring zoonotic diseases from their pets. If a client declines following a veterinarian’s advice, this should be documented in writing in the medical record. Veterinarians must advise clients to seek medical attention when they suspect a zoonotic infection has occurred. Veterinarians must also report occurrences of zoonotic disease, where public health laws dictate, and must also protect and educate their employees on preventative measures to stop the spread of infections.163,164,164 For information on prevention measures, consult the Recommendations section in this chapter and the Compendium of Veterinary Standard Precautions for Zoonotic Disease Prevention in Veterinary Personnel, published by the National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians (NASPHV) on line (see Box 93-6) and in print.467 Pets offer important physiologic and psychologic benefits for humans, especially for those who are ill (Box 99-4). The human-animal bond can be strong. Although illness and disability often alienate homebound humans with AIDS from their family, friends, and acquaintances, pets provide continued and unconditional companionship and help their owners overcome the deleterious effects of loneliness.93,466 Pets also provide pleasure, protection, and a sense of worth.93 It can be more detrimental to the well-being of isolated immunocompromised humans to lose their pet companions than to risk acquiring a zoonotic infection. Immunodeficient humans can develop emotional and physical limitations that prevent them from adequately caring for their pets. Extended, unanticipated hospitalizations and physical or financial limitations are often present. In addition, needs for preventive and disease-related veterinary care and feeding are expected. Veterinarians can advise their clients about the relative risks of and precautions to reduce the risk of zoonotic diseases and direct them to support groups to help them with home pet care. Veterinarians can also assist by offering their time and professional expertise to these local groups and potentially encourage donations to such organizations. Veterinarians can discreetly demonstrate their willingness to participate in a zoonosis prevention program by having signs or brochures in their waiting rooms. They must recognize that the increased cost of surveillance and treatment to prevent zoonoses can pose a financial difficulty for the client. In addition to home pet care, support groups can provide speakers, slide shows, newsletters, and brochures concerning pet care, zoonoses, and personal hygiene. They can provide assistance with screening suitable pets, financing pet health care, and educating pet assistants for routine care and emergencies. Numerous organizations are available to help with these needs (see Box 99-3).214,466 Although veterinarians generally are better prepared than physicians to answer questions about animal diseases and human risks, few patients view them as the primary providers of this information. Paradoxically, physicians seem to be uncomfortable discussing zoonotic diseases with their clients and view the veterinarian as playing a more important role in this service. Because physicians concentrate on infections in humans and veterinarians are minimally concerned about human illness, there is an inevitable gap in the education of the pet-owning public. In surveys of medical and veterinary professionals, physicians felt that public health officials and veterinarians should be more responsible for this task.32 When questioned about educating clients on the risk of zoonotic diseases, a much greater percentage of veterinarians felt comfortable than did physicians.210 Surprisingly, veterinarians and physicians rarely communicate with each other about this topic; physicians’ perceptions of relative risk did not match data on known disease transmission.210,387 More than 250 organisms are known to cause zoonotic infections, and approximately 30 to 40 involve companion animals (see Box 99-2). Of these, a selected few have been reported with greater frequency in humans with immunodeficiency and AIDS.15 The appearance of a few of these infections (cryptosporidiosis, Mycobacterium avium–complex [MAC] infection, cryptococcosis, salmonellosis, toxoplasmosis) has been used to define the onset of AIDS in humans with HIV infection. Some of the AIDS-related zoonoses are acquired directly from companion animals, and others are probably acquired from environmental exposure rather than from pets. The zoonoses described in the next section focus on those that have been associated with exposure of immunodeficient humans to companion animals (Table 99-1 and Web Table 99-1). Most of the zoonoses, with the exception of infections caused by B. henselae or zoophilic dermatophytes, are more commonly acquired from the environment or other vectors or hosts than from dogs or cats. Nevertheless, pet ownership does pose a risk to immunocompromised humans and should always be considered. TABLE 99-1 Veterinary Guidelines for Handling Dogs and Cats: Controlling Directly Transmitted Zoonoses Most Commonly Affecting Immunocompromised Peoplea C, Cat; D, dog; FA, fluorescent antibody; G, gastric Helicobacter organisms; I, intestinal Campylobacter organisms; NR, not recommended; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; R, recommended. aFor additional recommendations see: Scheftel JM, Elchos BL, Cherry B, et al. 2010. Compendium of veterinary standard precautions for zoonotic disease prevention in veterinary personnel. J Am Vet Med Assoc 237:1403–1422. WEB TABLE 99-1 Dog and Cat Zoonoses Important for the Human Immunocompromised Host AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CDAD, Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea; CDV, canine distemper virus; CNS, central nervous system; CPV, canine parvovirus; CSD, Cat scratch disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; FeLV, feline leukemia virus; FIV, feline immunodeficiency virus; GI, gastrointestinal; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICU, intensive care unit; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UTI, urinary tract infection. Bites are among the most common source of zoonoses, and immunocompromised humans have the greatest risk of developing a systemic infection as a result of bite wound injuries (see Chapter 51). Many organisms, such as Capnocytophaga and Pasteurella, which represent oropharyngeal flora, are frequently found in bite infections. In addition, many other aerobic and anaerobic bacteria have been isolated. Bites or scratches should always be washed immediately with soap and water. All individuals, especially those who are immunocompromised, should be advised to consult with a physician as soon as possible. Capnocytophaga canimorsus (formerly DF-2) is a gram-negative, rod-shaped organism that is found in the oral flora of dogs, cats, and other animals. C. canimorsus was first isolated in 1976 from a human patient with a dog bite and was named “dog-bite organism.” There is a separate group of Capnocytophaga (DF-1) that are found in the oral flora of humans. Altogether the Capnocytophaga genus consists of nine species (see Capnocytophaga, Chapter 51).189 The clinical manifestations of Capnocytophaga infection range from cellulitis to fulminant sepsis. Most cases in humans are associated with an underlying immune disorder. Although the condition is considered rare, it is likely that the infection occurs more frequently than realized because the organism is difficult to culture by routine methods. Individuals with splenectomy are well known to be at risk for this organism, but other conditions can render a patient functionally asplenic or hyposplenic, such as sickle cell disease, alcoholism, cirrhosis, and celiac sprue. Signs of infection are acute severe cellulitis and bacteremia, which may develop within 24 to 48 hours of the bite. The mortality associated with this particular organism has varied; one case series reported a 5% mortality rate,374 whereas others estimated a 35% mortality rate.464 Transmission of Capnocytophaga is generally from a dog bite, although other types of contact with dogs or cats are possible.425,494 In one review of 28 cases, a history of preceding cat or dog bite was found in 89% of cases.134 In the others, contamination may have been spread by contact with salivary secretions on mucosal or broken skin surfaces. Cats and dogs should not be allowed to lick open cuts or wounds. For further information on Capnocytophaga species, see Chapter 51. Pasteurella multocida is a gram-negative coccobacillus commonly found in the oral cavities of animals, with cats and dogs having particularly high rates of colonization. P. multocida is a leading cause of animal bite infections in both the immunocompetent and immunocompromised host. In the clinically healthy host, P. multocida generally causes infection of the skin and soft tissue, with swelling and inflammation around the site of a bite. Immunocompromised hosts can also develop local infection from P. multocida but are also predisposed to develop more invasive, systemic infections, including sepsis, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and meningitis. Newborn human infants exposed to dogs or cats at less than 1 month of age appear to have a high risk and typically develop meningitis.295,397 Cirrhosis of the liver is one of the most common predisposing conditions associated with severe Pasteurella infections,296 but other predisposing conditions such as neoplasia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and polycystic kidney disease have been reported.95,153,153 P. multocida is generally transmitted to individuals via animal bites, but other mechanisms of transmission, such as animal scratches and licking, are noteworthy. One individual with polycystic kidney disease acquired P. multocida in a leg ulcer from a lick by a pet dog, developed bacteremia and endocarditis, and subsequently died.249 Other instances of pets licking surgery-site incisions have been associated with infected wounds and sepsis.237 Inadvertent contact of cats with humans implanted with home peritoneal dialysis catheters has resulted in peritonitis.27,122,453,463 Similarly, urinary tract infection (UTI) with P. multocida was identified in a person with urinary anatomic abnormalities associated with prior surgery.334 The urgency of seeking treatment is illustrated by a case report of a 64-year-old man with cirrhosis who developed sepsis after a cat bite. Although he did seek medical care, it was approximately 48 hours after the bite, and he died within 72 hours of the bite.153 See Pasteurella in Chapter 51 for further information on this organism causing infections in humans. Several other organisms are unique to dogs and cats, and they produce severe infections in immunocompromised humans. Pasteurella dagmatis and Neisseria canis, both commensal organisms of the canine oral cavity, were isolated from a human with chronic bronchiectasis.8 Other organisms from dogs or cats, including Bergeyella zoohelcum, Neisseria animaloris, Neisseria zoodegmatis, and Capnocytophaga cynodegmi, have caused human infections. For additional information on these and other aerobic and anaerobic organisms associated with infections in humans caused by cat or dog bites or their oral secretions, see Chapter 51. Helicobacter infections occur in humans and their pets; however, many host-adapted species are involved (see Gastric Helicobacter Infections, Chapter 37). Helicobacter pylori, a primary human gastric commensal and pathogen, has been isolated in a laboratory cat colony in association with human exposure; however, it is considered unusual, and natural infections are unlikely. Epidemiologic studies do not show an association between cat ownership and H. pylori infection in humans.550 The presence of Helicobacter heilmannii, an animal pathogen, was found in a human with gastric erosions and in his two cats.148 Genetic analysis showed that the human and feline strains were closely related and that more than one strain can concurrently infect a human. One isolate from cats and humans was identical, suggesting zoonotic or anthroponotic spread. H. heilmannii was found in a boy with gastritis, and the same genetic strains were found in his dogs.157 Oral-to-oral transmission is the primary means of gastric Helicobacter spread between animals and humans, so contact with the oral cavities or saliva of pets should be avoided. Humans are most likely to acquire this infection from other humans, because they are the reservoirs for H. pylori and other human strains. Precautions to prevent infection should be taken, such as not sharing feeding utensils with humans or pets. For additional information on the zoonotic risks involving Helicobacter spp., see Chapter 37.

Zoonotic Infections of Medical Importance in Immunocompromised Humans

Immunodeficiencies in Humans

Pet Ownership

Zoonotic Risk

Occupational and Environmental Risks

Legal Implications for Veterinarians

Benefits of Pet Ownership

Support Groups

Pet Advisement

Diseases

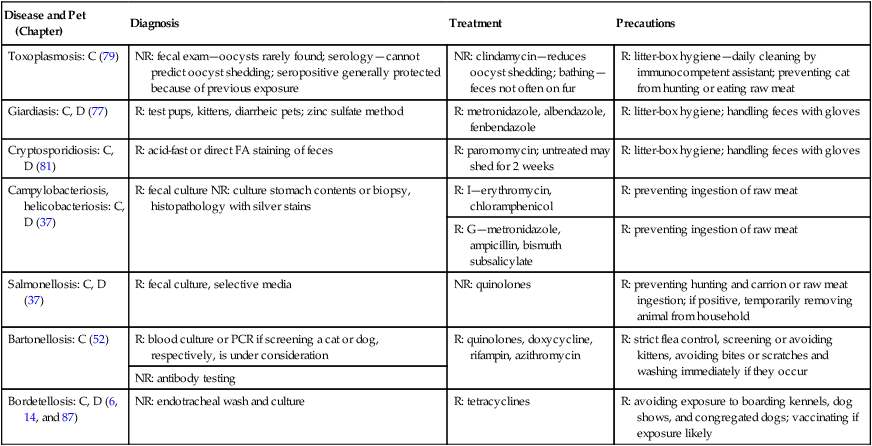

Disease and Pet (Chapter)

Diagnosis

Treatment

Precautions

Toxoplasmosis: C (79)

NR: fecal exam—oocysts rarely found; serology—cannot predict oocyst shedding; seropositive generally protected because of previous exposure

NR: clindamycin—reduces oocyst shedding; bathing—feces not often on fur

R: litter-box hygiene—daily cleaning by immunocompetent assistant; preventing cat from hunting or eating raw meat

Giardiasis: C, D (77)

R: test pups, kittens, diarrheic pets; zinc sulfate method

R: metronidazole, albendazole, fenbendazole

R: litter-box hygiene; handling feces with gloves

Cryptosporidiosis: C, D (81)

R: acid-fast or direct FA staining of feces

R: paromomycin; untreated may shed for 2 weeks

R: litter-box hygiene; handling feces with gloves

Campylobacteriosis, helicobacteriosis: C, D (37)

R: fecal culture NR: culture stomach contents or biopsy, histopathology with silver stains

R: I—erythromycin, chloramphenicol

R: preventing ingestion of raw meat

R: G—metronidazole, ampicillin, bismuth subsalicylate

R: preventing ingestion of raw meat

Salmonellosis: C, D (37)

R: fecal culture, selective media

NR: quinolones

R: preventing hunting and carrion or raw meat ingestion; if positive, temporarily removing animal from household

Bartonellosis: C (52)

R: blood culture or PCR if screening a cat or dog, respectively, is under consideration

R: quinolones, doxycycline, rifampin, azithromycin

R: strict flea control, screening or avoiding kittens, avoiding bites or scratches and washing immediately if they occur

NR: antibody testing

Bordetellosis: C, D (6, 14, and 87)

NR: endotracheal wash and culture

R: tetracyclines

R: avoiding exposure to boarding kennels, dog shows, and congregated dogs; vaccinating if exposure likely

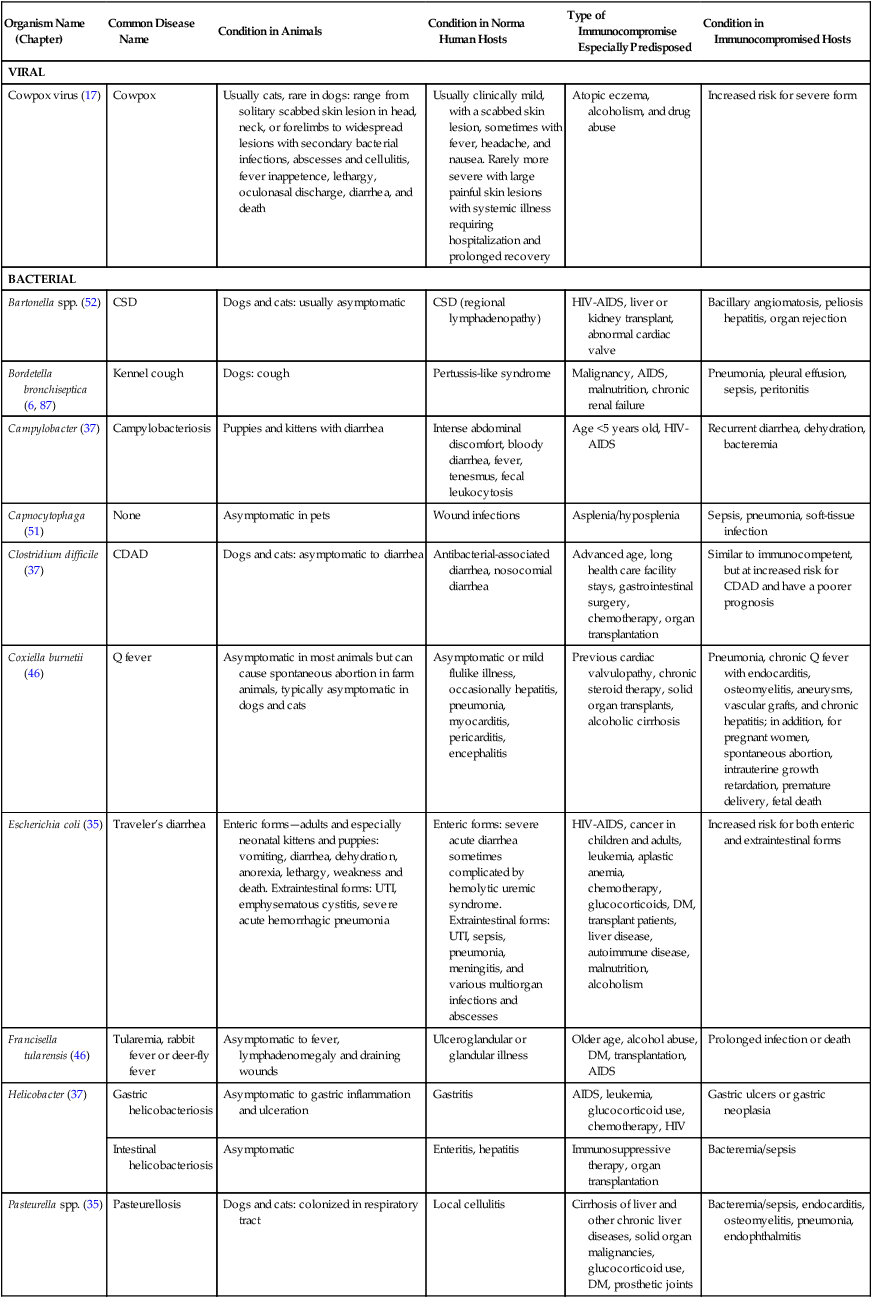

Organism Name (Chapter)

Common Disease Name

Condition in Animals

Condition in Norma Human Hosts

Type of Immunocompromise Especially Predisposed

Condition in Immunocompromised Hosts

VIRAL

Cowpox virus (17)

Cowpox

Usually cats, rare in dogs: range from solitary scabbed skin lesion in head, neck, or forelimbs to widespread lesions with secondary bacterial infections, abscesses and cellulitis, fever inappetence, lethargy, oculonasal discharge, diarrhea, and death

Usually clinically mild, with a scabbed skin lesion, sometimes with fever, headache, and nausea. Rarely more severe with large painful skin lesions with systemic illness requiring hospitalization and prolonged recovery

Atopic eczema, alcoholism, and drug abuse

Increased risk for severe form

BACTERIAL

Bartonella spp. (52)

CSD

Dogs and cats: usually asymptomatic

CSD (regional lymphadenopathy)

HIV-AIDS, liver or kidney transplant, abnormal cardiac valve

Bacillary angiomatosis, peliosis hepatitis, organ rejection

Bordetella bronchiseptica (6, 87)

Kennel cough

Dogs: cough

Pertussis-like syndrome

Malignancy, AIDS, malnutrition, chronic renal failure

Pneumonia, pleural effusion, sepsis, peritonitis

Campylobacter (37)

Campylobacteriosis

Puppies and kittens with diarrhea

Intense abdominal discomfort, bloody diarrhea, fever, tenesmus, fecal leukocytosis

Age <5 years old, HIV-AIDS

Recurrent diarrhea, dehydration, bacteremia

Capnocytophaga (51)

None

Asymptomatic in pets

Wound infections

Asplenia/hyposplenia

Sepsis, pneumonia, soft-tissue infection

Clostridium difficile (37)

CDAD

Dogs and cats: asymptomatic to diarrhea

Antibacterial-associated diarrhea, nosocomial diarrhea

Advanced age, long health care facility stays, gastrointestinal surgery, chemotherapy, organ transplantation

Similar to immunocompetent, but at increased risk for CDAD and have a poorer prognosis

Coxiella burnetii (46)

Q fever

Asymptomatic in most animals but can cause spontaneous abortion in farm animals, typically asymptomatic in dogs and cats

Asymptomatic or mild flulike illness, occasionally hepatitis, pneumonia, myocarditis, pericarditis, encephalitis

Previous cardiac valvulopathy, chronic steroid therapy, solid organ transplants, alcoholic cirrhosis

Pneumonia, chronic Q fever with endocarditis, osteomyelitis, aneurysms, vascular grafts, and chronic hepatitis; in addition, for pregnant women, spontaneous abortion, intrauterine growth retardation, premature delivery, fetal death

Escherichia coli (35)

Traveler’s diarrhea

Enteric forms—adults and especially neonatal kittens and puppies: vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, anorexia, lethargy, weakness and death. Extraintestinal forms: UTI, emphysematous cystitis, severe acute hemorrhagic pneumonia

Enteric forms: severe acute diarrhea sometimes complicated by hemolytic uremic syndrome. Extraintestinal forms: UTI, sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis, and various multiorgan infections and abscesses

HIV-AIDS, cancer in children and adults, leukemia, aplastic anemia, chemotherapy, glucocorticoids, DM, transplant patients, liver disease, autoimmune disease, malnutrition, alcoholism

Increased risk for both enteric and extraintestinal forms

Francisella tularensis (46)

Tularemia, rabbit fever or deer-fly fever

Asymptomatic to fever, lymphadenomegaly and draining wounds

Ulceroglandular or glandular illness

Older age, alcohol abuse, DM, transplantation, AIDS

Prolonged infection or death

Helicobacter (37)

Gastric helicobacteriosis

Asymptomatic to gastric inflammation and ulceration

Gastritis

AIDS, leukemia, glucocorticoid use, chemotherapy, HIV

Gastric ulcers or gastric neoplasia

Intestinal helicobacteriosis

Asymptomatic

Enteritis, hepatitis

Immunosuppressive therapy, organ transplantation

Bacteremia/sepsis

Pasteurella spp. (35)

Pasteurellosis

Dogs and cats: colonized in respiratory tract

Local cellulitis

Cirrhosis of liver and other chronic liver diseases, solid organ malignancies, glucocorticoid use, DM, prosthetic joints

Bacteremia/sepsis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, pneumonia, endophthalmitis

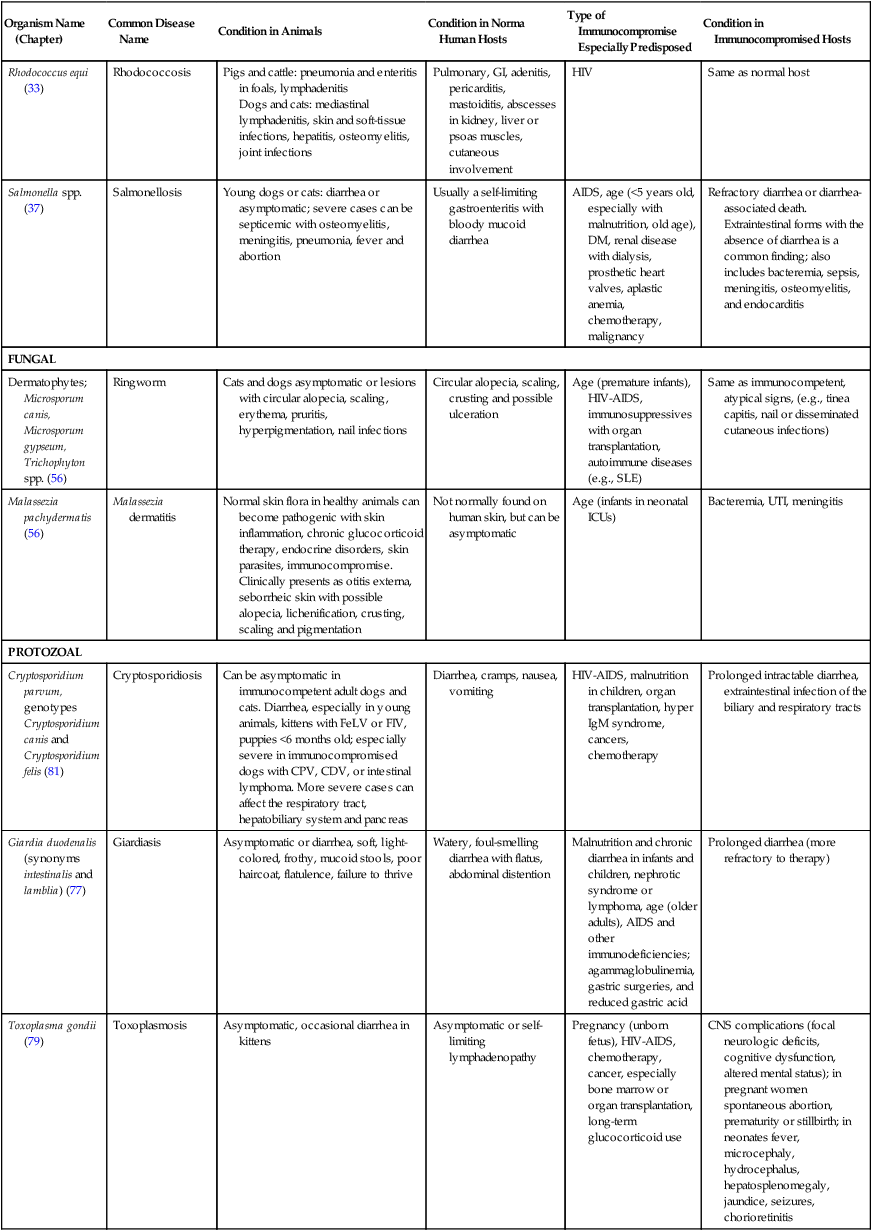

Rhodococcus equi (33)

Rhodococcosis

Pigs and cattle: pneumonia and enteritis in foals, lymphadenitis

Dogs and cats: mediastinal lymphadenitis, skin and soft-tissue infections, hepatitis, osteomyelitis, joint infections

Pulmonary, GI, adenitis, pericarditis, mastoiditis, abscesses in kidney, liver or psoas muscles, cutaneous involvement

HIV

Same as normal host

Salmonella spp. (37)

Salmonellosis

Young dogs or cats: diarrhea or asymptomatic; severe cases can be septicemic with osteomyelitis, meningitis, pneumonia, fever and abortion

Usually a self-limiting gastroenteritis with bloody mucoid diarrhea

AIDS, age (<5 years old, especially with malnutrition, old age), DM, renal disease with dialysis, prosthetic heart valves, aplastic anemia, chemotherapy, malignancy

Refractory diarrhea or diarrhea-associated death. Extraintestinal forms with the absence of diarrhea is a common finding; also includes bacteremia, sepsis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis

FUNGAL

Dermatophytes; Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton spp. (56)

Ringworm

Cats and dogs asymptomatic or lesions with circular alopecia, scaling, erythema, pruritis, hyperpigmentation, nail infections

Circular alopecia, scaling, crusting and possible ulceration

Age (premature infants), HIV-AIDS, immunosuppressives with organ transplantation, autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE)

Same as immunocompetent, atypical signs, (e.g., tinea capitis, nail or disseminated cutaneous infections)

Malassezia pachydermatis (56)

Malassezia dermatitis

Normal skin flora in healthy animals can become pathogenic with skin inflammation, chronic glucocorticoid therapy, endocrine disorders, skin parasites, immunocompromise. Clinically presents as otitis externa, seborrheic skin with possible alopecia, lichenification, crusting, scaling and pigmentation

Not normally found on human skin, but can be asymptomatic

Age (infants in neonatal ICUs)

Bacteremia, UTI, meningitis

PROTOZOAL

Cryptosporidium parvum, genotypes Cryptosporidium canis and Cryptosporidium felis (81)

Cryptosporidiosis

Can be asymptomatic in immunocompetent adult dogs and cats. Diarrhea, especially in young animals, kittens with FeLV or FIV, puppies <6 months old; especially severe in immunocompromised dogs with CPV, CDV, or intestinal lymphoma. More severe cases can affect the respiratory tract, hepatobiliary system and pancreas

Diarrhea, cramps, nausea, vomiting

HIV-AIDS, malnutrition in children, organ transplantation, hyper IgM syndrome, cancers, chemotherapy

Prolonged intractable diarrhea, extraintestinal infection of the biliary and respiratory tracts

Giardia duodenalis (synonyms intestinalis and lamblia) (77)

Giardiasis

Asymptomatic or diarrhea, soft, light-colored, frothy, mucoid stools, poor haircoat, flatulence, failure to thrive

Watery, foul-smelling diarrhea with flatus, abdominal distention

Malnutrition and chronic diarrhea in infants and children, nephrotic syndrome or lymphoma, age (older adults), AIDS and other immunodeficiencies; agammaglobulinemia, gastric surgeries, and reduced gastric acid

Prolonged diarrhea (more refractory to therapy)

Toxoplasma gondii (79)

Toxoplasmosis

Asymptomatic, occasional diarrhea in kittens

Asymptomatic or self-limiting lymphadenopathy

Pregnancy (unborn fetus), HIV-AIDS, chemotherapy, cancer, especially bone marrow or organ transplantation, long-term glucocorticoid use

CNS complications (focal neurologic deficits, cognitive dysfunction, altered mental status); in pregnant women spontaneous abortion, prematurity or stillbirth; in neonates fever, microcephaly, hydrocephalus, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, seizures, chorioretinitis

Spread by Bites, Scratches, or Close Physical Mucosal or Skin Contact

Capnocytophagiosis

Pasteurellosis

Gastric Helicobacteriosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Zoonotic Infections of Medical Importance in Immunocompromised Humans