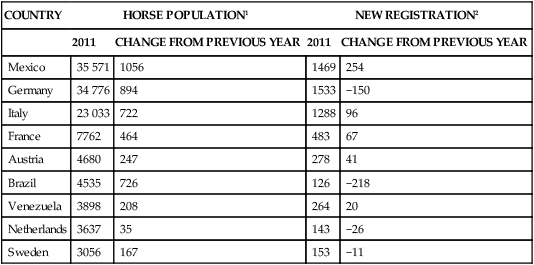

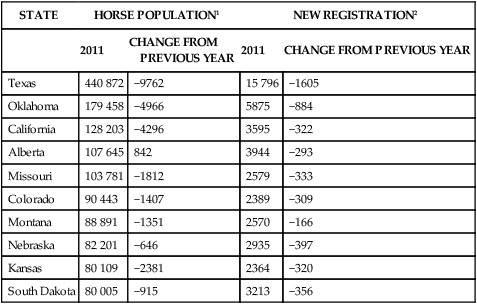

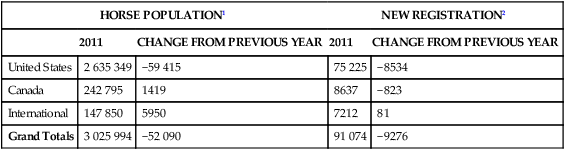

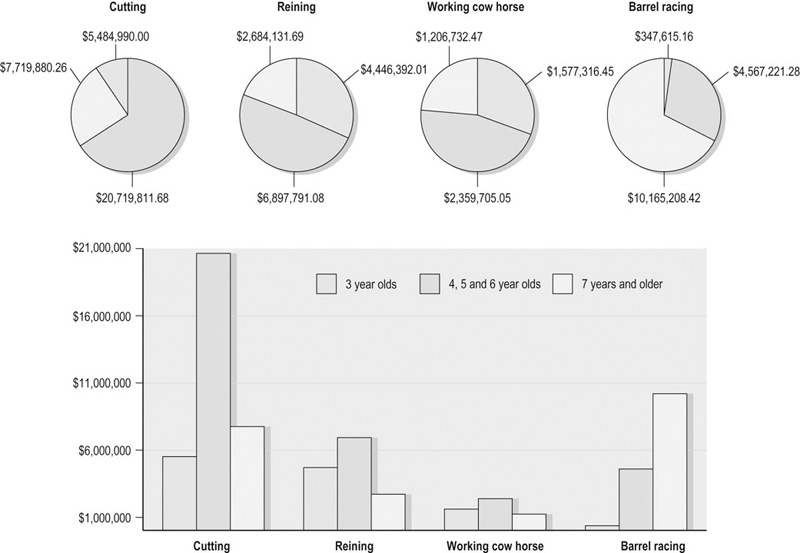

The American Quarter Horse Association is the largest equine breed association in the world with over three million horses registered.1 Reining became a sport recognized by the International Equestrian Federation (FEI) in 2000 and is one of the world’s fastest-growing equestrian sports. The midwestern region of North America has the highest population of Quarter Horses (see Tables 54.1–54.3). Of the European countries, Italy and Germany have the highest number of registered Quarter Horses, yet the total number registered internationally comprises less than 5% of the population1 (see Table 54.1). Annual purses associated with many of the western equestrian disciplines continue to increase steadily on a year-by-year basis. In the past decade, reining competition payouts increased over 150% from $4 966 323 in 2000 to $12 497 450 in 2010; annual purse statistics from this and other selected western events in 2011 are presented in Figure 54.1.2,3 While many athletes compete well into their teenage years, horses actively competing in roping and barrel racing tend to be older, and may have trained or competed in other disciplines when younger. The cutting, reining, and cow horse industries have the most developed payout structures focused on age-categorized competitions most commonly referred to as futurities (for three year olds) and derbies (for 4–6 year olds). Training intensity is high, especially as two and three year olds. Rare elite athletes cross compete in both reining and reined cow horse events at the futurity and derby level. The phenotype of Quarter Horse utilized is somewhat sport dependent. Horses used for barrel racing often have more Thoroughbred influence in their pedigree and thus are taller with longer, less bulky muscles. Cutting horses tend to have the smallest frame of the western sport horses. Horses used for roping events differ somewhat based on their specific role; heeling horses tend to be smaller framed in comparison to heading horses. Table 54.1 Top 10 countries outside of the United States for registered Quarter Horses Table 54.2 Top 10 states/provinces in North America AQHA populations Table 54.3 Total AQHA population and registrations 1Figures reflect elimination of all horses age 25 and over unless the owners(s) submitted documentation proving the horse is living. 2Reflects the number of American Quarter Horses registered during 2011 to residents within the state, province or country. While there is some welfare concern regarding the potential deleterious impact of intense early training on the young horse’s musculoskeletal system, data to substantiate these concerns in western performance horses is lacking. Some sectors of the industry are skeptical that starting young horses a year later would decrease the incidence of athletic injury in the cutting industry.4 Furthermore, research in young Thoroughbreds suggests that imposing controlled exercise at a very early age (three weeks to 18 months) is not detrimental to bone and joint development, and may in fact be beneficial.5,6 A number of factors including athletic potential, injury, trainability, and economics can impact the successful development of a competitive western athlete. In contrast to the racing industry, there is a paucity of specific information regarding wastage due to athletic injuries in the western performance industry. Performance statistics from 2011 on offspring sired by the top 20 junior stallions in the cutting and reining industries indicates approximately 32% of performance-aged offspring become money earners.7 While these statistics do not include non-money earning offspring that are shown, by extrapolation, this performance information is somewhat similar to findings in the Thoroughbred industry where approximately 27% of foals produced by Thoroughbred mares each year go on to race as two and four year olds.8 Western performance horses are typically started under saddle as two and three year olds, regardless of discipline. It is not uncommon for those intended to compete in futurity events (reining, cutting, working cow horse) to be started lightly as a long yearling. Training regimens in elite futurity prospects are essentially continual through the horse’s second and third years and this repetition and intensity predisposes these athletes to certain injuries.9 All western athletes are gradually trained by repetition of event-specific maneuvers to increase precision and speed. Once a solid base of aerobic fitness is established after 30–60 days, anaerobic work is often gradually introduced with short episodes of high-intensity exercise 2–3 days a week. The activity utilized for this purpose varies with the different sports. Although limited research has been published on physiologic responses during western events, exercise associated with fast canter work (e.g. large fast circles), run downs, sliding stops and rollbacks, fast spins, intense cutting activity, and calf roping are all associated with heart rates typical of anaerobic work.10–13 Most often anaerobic work is simply achieved as one executes these various maneuvers and repeats them at speed in the practice pen for the various sports. In contrast, some barrel horse trainers integrate fast speed work while exercising horses in fields or at local race tracks. Finished horses of all disciplines that are fit are typically worked for 30–45 minutes, 3–5 days a week to maintain fitness. Older weekend cutting horses, once trained and fit, may be worked on cattle less than once a week. Some trainers also utilize mechanical flags to assist training the stop and proper reaction timing. Roping horses and barrel racing horses that are transported by road almost every weekend to compete may receive minimal routine aerobic exercise between events to maintain fitness during the competition season. Maintenance of proper mediolateral balance and normal hoof pastern axis is critical as in other equine disciplines. Horses often remain unshod during early training, and on occasion even later during competition, in the front feet, if the individual has exceptional hoof quality and conformation. In general, cutting horses often have smaller feet. Currently, there appears to be a trend toward leaving aged event cutting horses barefoot as they often only train and compete in deeper sand footing. Steel keg shoes are also common, especially in older ‘weekend cutters’ as they often do ranch work in different footing at home (Grant Rezabek, personal communication, 2012). Roping and barrel horses are often shod with steel keg, rim, or natural balance shoes on the front feet and either keg or rim shoes on hind feet.14–16 The front feet of reining horses are often shod with a squared or rounded toe, and the ground surface may be beveled around to the quarters or heels. The shoe is often set back at the toe to further enhance breakover, which is thought to promote front foot travel in the stop. Circumferential beveling may reduce medial and lateral torsional forces during the turn around. The hind feet of reining horses are shod with sliding plates which are flat, elongated, wide webbed steel shoes in which the nails are countersunk and the bottom of the shoe is polished with a grinder to increase the distance of the sliding stop. Typically, young reining horses have ‘starting plates’ ( The form of leg protection utilized can vary, but most often some form of splint boot, usually neoprene, or a felt polo wrap is used for the front limbs of all western performance horses in training and competition. In reining horses that interfere at the carpus during the turnaround (spins), a variety of knee boots are used during training (Fig. 54.3). In addition, if the sliding stop is incorporated (reining, working cow horse, calf roping, heeling) some form of skid boot is usually applied to the hindlimbs. Most commonly this gear just protects the fetlock (Fig. 54.4A), while some reining horses that stop very deep may require skid boots that cover the hock to prevent excoriation (Fig. 54.4B

Veterinary aspects of training and competing western performance horses

Overview of the sport

Demographics

COUNTRY

HORSE POPULATION1

NEW REGISTRATION2

2011

CHANGE FROM PREVIOUS YEAR

2011

CHANGE FROM PREVIOUS YEAR

Mexico

35 571

1056

1469

254

Germany

34 776

894

1533

−150

Italy

23 033

722

1288

96

France

7762

464

483

67

Austria

4680

247

278

41

Brazil

4535

726

126

−218

Venezuela

3898

208

264

20

Netherlands

3637

35

143

−26

Sweden

3056

167

153

−11

STATE

HORSE POPULATION1

NEW REGISTRATION2

2011

CHANGE FROM

PREVIOUS YEAR

2011

CHANGE FROM PREVIOUS YEAR

Texas

440 872

−9762

15 796

−1605

Oklahoma

179 458

−4966

5875

−884

California

128 203

−4296

3595

−322

Alberta

107 645

842

3944

−293

Missouri

103 781

−1812

2579

−333

Colorado

90 443

−1407

2389

−309

Montana

88 891

−1351

2570

−166

Nebraska

82 201

−646

2935

−397

Kansas

80 109

−2381

2364

−320

South Dakota

80 005

−915

3213

−356

HORSE POPULATION1

NEW REGISTRATION2

2011

CHANGE FROM PREVIOUS YEAR

2011

CHANGE FROM PREVIOUS YEAR

United States

2 635 349

−59 415

75 225

−8534

Canada

242 795

1419

8637

−823

International

147 850

5950

7212

81

Grand Totals

3 025 994

−52 090

91 074

−9276

Wastage

Training

Farriery and protective legwear

inch wide with short trailers) applied during the first 3–6 months of training. Over time, the width of the shoe (and length of trailer) is often increased; the toe is also commonly fashioned similar to a snow ski tip. In finished reining horses sliding plates most often range from 1 or

inch wide with short trailers) applied during the first 3–6 months of training. Over time, the width of the shoe (and length of trailer) is often increased; the toe is also commonly fashioned similar to a snow ski tip. In finished reining horses sliding plates most often range from 1 or  inches wide (Fig. 54.2). They can also be shod with a slightly longer toe and a lower angle thought to promote a longer sliding stop. Similar sliding plates are applied in working cow horses, calf roping horses and some heel horses to promote the sliding stop. Because more traction is required for working cow horses in the fence work, and in all of the aforementioned disciplines, the stop is most often shorter and deeper, the sliding plates used are not as wide and have shorter trailers than those applied to reining horses.

inches wide (Fig. 54.2). They can also be shod with a slightly longer toe and a lower angle thought to promote a longer sliding stop. Similar sliding plates are applied in working cow horses, calf roping horses and some heel horses to promote the sliding stop. Because more traction is required for working cow horses in the fence work, and in all of the aforementioned disciplines, the stop is most often shorter and deeper, the sliding plates used are not as wide and have shorter trailers than those applied to reining horses.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterinary aspects of training and competing western performance horses