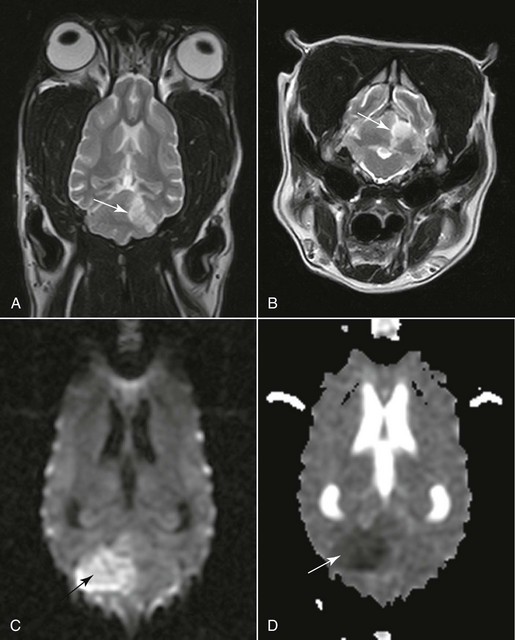

Chapter 241 With limited stores the brain relies on a permanent supply of glucose and oxygen to maintain ionic pump function (see Chapter 228). When perfusion pressure falls to critical levels, ischemia develops, progressing to infarction if hypoperfusion persists long enough. An infarct is an area of compromised or necrotic brain parenchyma caused by a focal occlusion of one or more blood vessels. It may be caused either by vascular obstruction that develops within the affected vessels (thrombosis) or by obstruction by material that originates from another vascular bed and travels to the brain (thromboembolism). Suspected underlying causes identified in histopathologically confirmed cases included septic thromboemboli, atherosclerosis associated with primary hypothyroidism and with hypertriglyceridemia in miniature schnauzers, aberrant parasitic migration (Cuterebra spp.) or parasitic emboli (Dirofilaria immitis), embolic metastatic tumor cells, intravascular lymphoma, embolism with an aortic or cardiac source, and fibrocartilaginous embolism. In our study (Garosi, 2005) using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a concurrent medical condition was detected in just over 50% of dogs affected by brain infarcts. Hypertension was documented in 30% of dogs. In these dogs chronic kidney disease and hyperadrenocorticism were the most commonly suspected underlying causes of the hypertension. No underlying cause could be identified antemortem in nearly half of the dogs. An infarct of unknown origin is called cryptogenic. No age, sex, or breed predisposition was identified. However, cavalier King Charles spaniels and greyhounds appeared overrepresented. Imaging studies of the brain (computed tomography [CT], conventional and functional MRI) are necessary to confirm the suspicion of stroke, define the vascular territory involved and the extent of the lesion, and distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (Figure 241-1). Imaging studies also are necessary to rule out other causes of neurologic deficit such as tumor, head trauma, and encephalitis. (See References and Suggested Reading for more details.) Figure 241-1 A and B, Dorsal and transverse T2-weighted magnetic resonance images of the brain showing a cerebellar territorial infarct (arrow) in the vascular territory of the rostral cerebellar artery. The sharp demarcation, lack of mass effect, and gray matter involvement are typical of an infarct. C, Diffusion-weighted image of a large ischemic cerebellar infarct (arrow) in a different dog than shown in A and B. D, Corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient map of the infarct (arrow). The nature of the lesion is confirmed because of the hyperintensity and hypointensity of the lesion, respectively. (A and B courtesy Dr. Cristian Falzone.) Ancillary diagnostic tests in ischemic stroke should focus on evaluating the animal for systemic hypertension (and underlying causes; see Chapter 169), endocrine disease (hyperadrenocorticism, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus), kidney disease (especially protein-losing nephropathy), heart disease (a much greater risk factor in cats with cardiomyopathy), and metastatic disease. In cases of ischemic stroke, D-dimer assays and antithrombin III evaluation should be included routinely in the screening tests to identify thromboembolic disease as a possible cause of ischemic stroke. A D-dimer assay is considered to be a more useful test for detecting thromboembolic disease in dogs than traditional tests currently in use (platelet count and clotting times). In cases of hemorrhagic stroke, diagnostic tests should be targeted at screening the animal for a coagulation disorder (and underlying causes), hypertension (and underlying causes), and metastatic disease (particularly hemangiosarcoma).

Vascular Disease of the Central Nervous System

Cerebrovascular Accident (or Stroke)

Ischemic Stroke

Clinical Presentation of Stroke

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine