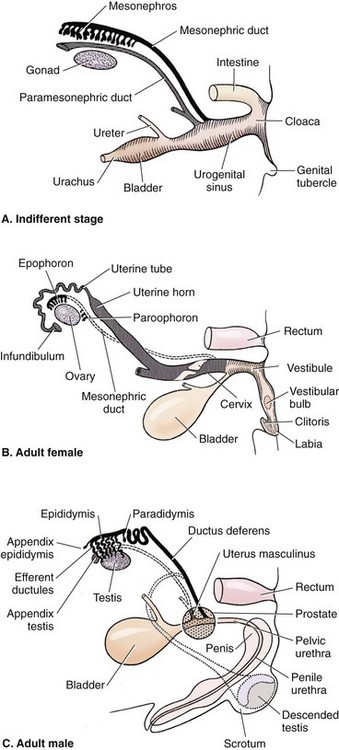

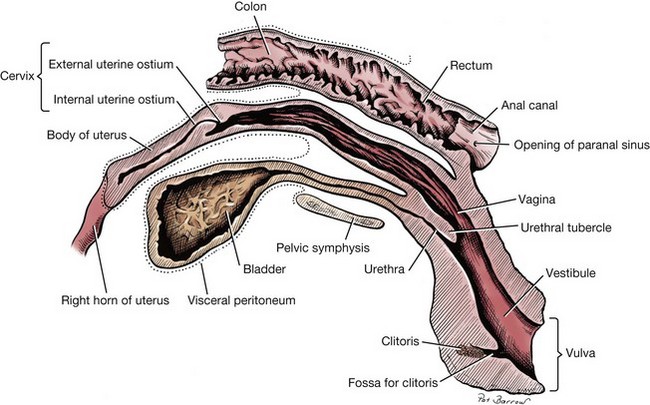

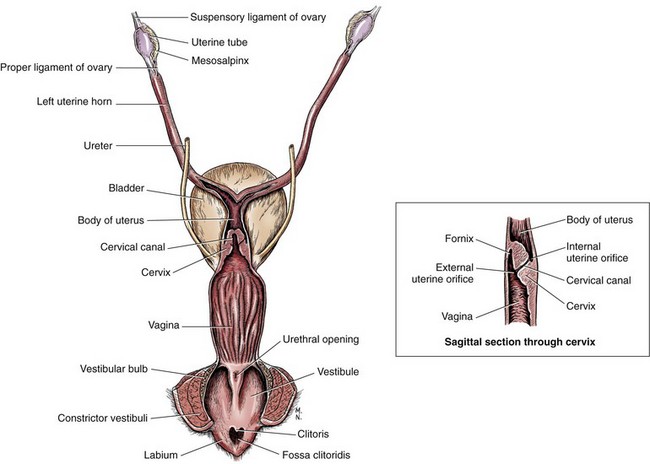

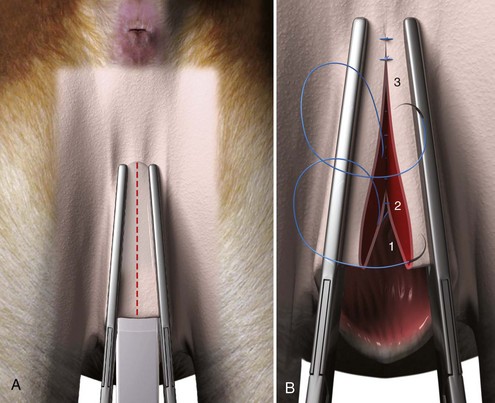

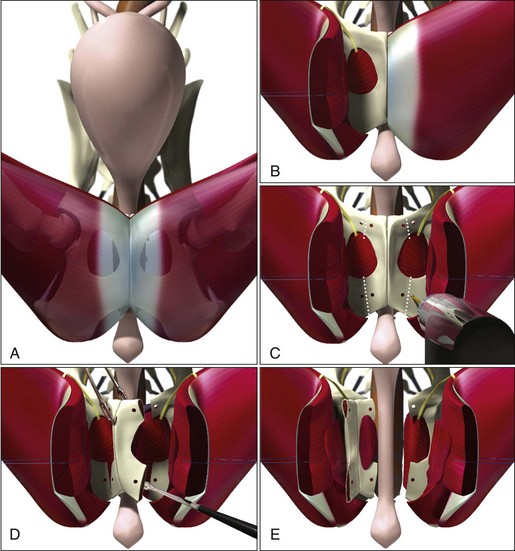

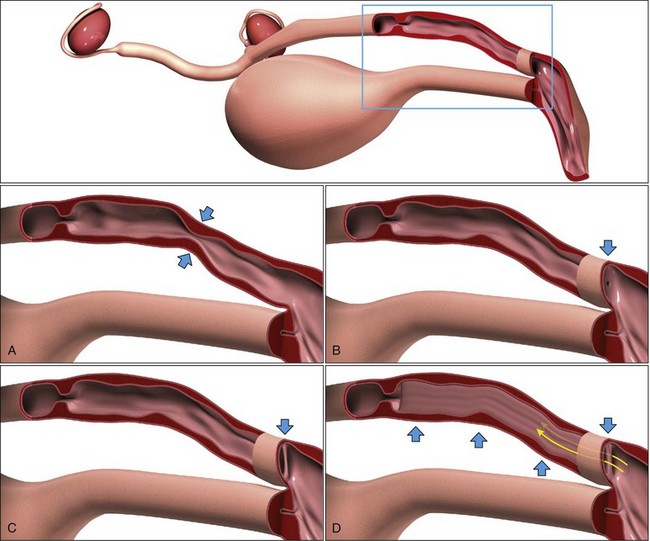

Chapter 110 During fetal development, the canine external genitalia are initially contiguous with the hindgut, opening at a common cloaca (Figure 110-1). As sexual differentiation occurs, the rectum and urogenital sinus are separated by a caudally progressing urorectal septum, forming independent gastrointestinal and urogenital systems. Laterally located cloacal folds fuse along a midline genital raphe, separating the anal opening from the external genitalia. In females, the cranial vagina is formed from fusion of the paired paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts, creating a single tube that unites with the more caudally located urogenital sinus to produce the vestibulovaginal junction or cingulum. The genital tubercle, which is analogous to the penis in males, is retained as the vestigial clitoris in adult females. Unlike the bicornuate uterus of rabbits and rodents, complete fusion of the paramesonephric ducts produces a single cervix in dogs. The cervix is positioned obliquely in the sagittal plane, with a large blind-ended fornix located ventral to the external uterine orifice (Figure 110-2). The vagina has prominent longitudinal folds in the mucosa, which is composed of nonglandular, stratified squamous epithelium. An outer coating of striated urethral muscle is confluent with the distal third of the vagina, contributing to the voluntary control of urination by constricting the urethra as it enters the vestibule.3,37 The vestibulovaginal junction is demarcated by a transverse, palpable mucosal ridge and by a transition from light pink, redundant vaginal mucosal folds to smooth, red vestibular mucosa. The urethral tubercle enters the ventral aspect of the vagina approximately 1 cm caudal to the vestibulovaginal junction. The labia of the vulva should meet on the midline to cover the clitoris, which is located in the clitoral fossa, 3 cm cranial to the vulvar fissure (Figure 110-3). The blood supply to the vagina, urethra, and vestibule is provided by branches of the vaginal artery, which arises from the internal pudendal artery. The vulva is supplied by branches of the external pudendal artery. Venous drainage mirrors arterial supply. Whereas lymphatics of the vagina and vestibule drain into the internal iliac lymph nodes, the external genitalia drain into the superficial iliac nodes. Autonomic innervation is derived from the pelvic plexus and sensory innervation arises from the pudendal nerve. Anatomic features of the female genitalia are variable and are affected by breed, conformation, and hormonal status.42 In particular, the diameter of the vagina and vestibulovaginal junction varies with body weight and even changes throughout stages of the estrous cycle, making it very difficult to provide reference ranges that are clinically applicable.43 Increased estrogen levels during proestrus can also cause changes in the appearance of the external genitalia, with swelling of the vulva and the presence of a serosanguineous discharge. Occurrence of estrus is accompanied by increases in serum progesterone concentrations to 6 to 8 ng/mL, cornification of epithelial cells on vaginal cytology, and changes in the endoscopic appearance of the vaginal mucosa.16 Although quantitative differences in bacterial flora of the canine vagina are noted in each stage of the estrus cycle, a mixed resident population of aerobes, anaerobes, mycoplasma, and Ureaplasma spp. are expected in 95% of vaginal cultures from normal intact bitches.5,9,28,33 In a study of 59 intact dogs, Pasteurella multocida, ß-hemolytic Streptococcus spp., and Escherichia coli were the three most common isolates.5 Clinical signs associated with diseases of the vagina or vulva include vaginal discharge, alterations in urination behavior, excessive licking at the perivulvar region, and a visible mass protruding from the vulvar fissure. Physical examination should begin with a thorough evaluation of the urethra and intrapelvic vagina via rectal palpation. Direct digital examination of the canine vestibule and vagina may then be performed using aseptic technique. General anesthesia is recommended for digital examination of the vagina in dogs with suspected vestibulovaginal stenosis to prevent muscle spasm during evaluation.19 Cytology and microbial culture of vaginal fluid may be useful diagnostic aids but must be obtained using the proper technique and examined in coordination with other information. Serosanguineous or mucoid discharge is a normal finding during proestrus and should not be interpreted as an abnormal finding in an intact female. Cytology of vaginal exudate is primarily useful in diagnosing inflammation because neutrophils are not expected to be present in large numbers during any stage of the cycle except for early diestrus.30 The presence of large numbers of neutrophils in vaginal cytology from a spayed dog or degenerate neutrophils in a sample from any dog are indicative of a pathologic inflammatory condition. Because bacteria are nearly always present in the normal vagina, microbial culture is rarely indicated as a diagnostic aid. Rare exceptions include situations in which a bacterial pathogen (e.g., Brucella canis) is suspected or when culture and sensitivity results are required to direct ancillary antibiotic therapy for a separate primary disease process. When culture is desired, cultures must be obtained from the anterior vagina using a guarded culture swab to minimize contamination and should be quantitated to aid in interpretation of results.33 Imaging of the vagina and vestibule is frequently indicated to rule out congenital or neoplastic diseases that are contributing to clinical signs. Historically, contrast vaginourethrograms were used to aid in diagnosis of congenital anomalies and neoplasms, with a particular focus on detection of stenotic lesions at the vestibulovaginal junction.8 Among the wide range of dog breeds, however, variations in hormonal status and body weight make interpretation of these findings almost impossible.43 As a result, vaginoscopy has largely supplanted contrast radiography as the most useful imaging technique in evaluation of vaginal disorders. In female dogs and cats weighing 3 to 5 kg body weight, urogenital endoscopy may be performed using an extended length, rigid, 2.7-cm cystoscope in a 10-Fr operating sheath. A larger 4-mm scope and 19-Fr sheath can be used in dogs weighing more than 10 kg.21 Examinations are performed with the patient anesthetized and placed in lateral or dorsal recumbency. With the vulvar labia digitally apposed to prevent backflow, the vagina is infused by gravity with room temperature or chilled sterile saline to dilate the vaginal vault and minimize hemorrhage. Using this technique, the urethra, urinary bladder, vagina, and vestibulovaginal junction may be examined endoscopically to rule out ureteral ectopia, persistent hymen, and urinary or genital neoplasia. Dogs with chronic vaginitis frequently have nonspecific, nodular, inflammatory lesions and visible hyperemia in the vestibular mucosa. Biopsy samples of suspicious lesions are easily obtained using flexible endoscopic biopsy forceps placed through the channel in the operating sheath. Vaginal and vestibular lesions are most frequently approached by episiotomy. The patient is placed in a perineal position with the pelvic limbs and perineum suspended over the end of the surgical table. Padding should be placed between the table edge and the cranial thigh to avoid inadvertent nerve or muscle injury. Patients in a head-down position may require intermittent or continuous ventilator assistance. The perineal skin is shaved and aseptically prepared; the vestibule may be cleansed with dilute Betadine solution before surgery. The skin is incised, starting at the dorsal commissure of the vulva and extending along the perineal raphe toward the anus (Figure 110-4). The dorsal extent of the vestibule can be assessed by inserting a blunt instrument into the vulvar fissure and directing it dorsally until the limits of the vestibule are determined. This instrument may also be retained to provide resistance during scalpel incision and to prevent inadvertent trauma to the underlying tissue. The incision is progressively deepened until the vestibular constrictor muscle and mucosa have been transected. Alternatively, a single-stage full-thickness incision can be performed using sharp Mayo scissors. Hemostasis is achieved through judicious use of electrocoagulation or by placement of atraumatic Doyen forceps across the tissues lateral to the incision edges. After placement of a self-retaining Gelpi or Weitlaner retractor, the clitoral fossa, vestibule, urethral tubercle, and vestibulovaginal junction can be visualized. Catheterization of the urethra is typically performed to identify this structure and avoid iatrogenic injury before further procedures are initiated. Closure of the mucosa and muscular layers is performed separately using a rapidly absorbed suture material in a continuous or interrupted appositional pattern (see Figure 110-4). The skin is closed routinely, and an Elizabethan collar is placed immediately after surgery to prevent self-trauma. Opioids are also required in the first 12 to 24 hours after surgery. Application of cool packs (10 minutes every 4 hours) and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory analgesics provide analgesia and reduce postoperative swelling. For extraluminal lesions or for more aggressive surgical resection of intraluminal or mural lesions of the vagina, a ventral approach to the pelvic viscera may be required.2,11 The pubic symphysis is exposed through a caudal ventral midline incision, and the adductor muscles are elevated (Figure 110-5). Access to the intrapelvic viscera may be performed through a sagittal pubic osteotomy; if greater exposure is required, a flap of pelvic bone can be removed.2,4,35 Bilateral pubic and ilial osteotomies are performed after predrilling holes on either side of the proposed osteotomy locations. The obturator nerve is identified at the cranial aspect of the foramen and is preserved. The internal obturator muscle is dissected from one side of the osteotomized segment, and the bone flap is displaced laterally to allow exposure of the intrapelvic vagina and urethra. Repair of the pelvis is performed using cerclage wires or monofilament sutures that are placed through the predrilled holes. Muscles, subcutaneous tissues, and skin are closed routinely. Exercise is limited for 6 weeks after surgery to aid in healing of the pelvic flap. In some patients, the pubis can be removed completely and the defect closed by apposing surrounding musculature. Vestibulovaginal Stenotic Lesions Developmental anomalies that contribute to stenosis at the vestibulovaginal region are the result of retained epithelial tissue at the point of fusion of the paired paramesonephric ducts in the sagittal plane (a vaginal septum) or at the transverse junction of the paramesonephric ducts with the urogenital sinus (an imperforate hymen) in the area of the vestibulovaginal junction. Vertical septa can range from a thin band of tissue to a division several centimeters long that extends cranially into the vagina. More rarely, dogs will have an elongated, hypoplastic region in the vagina just cranial to the cingulum (Figure 110-6). Dogs with vestibulovaginal stenosis may be presented for a variety of clinical signs, including difficulty or pain associated with breeding, recurrent vaginitis, hydrocolpos (fluid accumulation in the vagina), or recurrent urinary tract infections.14,19,34,40,41 Although urinary incontinence is often a concurrent finding, anomalies at the vestibulovaginal region are unlikely to represent the primary cause of this condition, and surgical therapy is unlikely to improve continence.19 The clinical diagnosis of vestibulovaginal stenosis may be made on digital examination under general anesthesia.19 All dogs have some degree of narrowing at this area, however, and considerable experience is necessary to differentiate normal from abnormal findings. Contrast radiography may provide further information on the degree of vestibulovaginal stenosis.8 Results must be interpreted with caution because this technique is unable to illustrate thin vertical bands and no reference ranges for cingulum diameter or vestibulovaginal ratio have been established in dogs.43 Because of the difficulty in interpreting contrast radiography and the wide availability of endoscopic equipment in modern veterinary practice, direct visualization of the vestibulovaginal junction is typically performed using vaginoscopy. Endoscopic examination of the entire urogenital tract should be completed to rule out concurrent ureteral ectopia, urogenital neoplasia, patent urachus, or urolithiasis that may be contributing to clinical signs. In dogs with thin vertical bands, resection of the band may be performed with endoscopic guidance using an Nd:YAG (neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminium-garnet) laser44 or by use of standard endoscopic scissors.

Vagina, Vestibule, and Vulva

Embryology

Anatomy and Physiology

Diagnostic Evaluation

Cytology and Culture

Endoscopy

Surgical Approaches

Ventral Approach to the Vagina

Congenital Anomalies

Pathophysiology

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Vagina, Vestibule, and Vulva

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue