Chapter 11 Udder and teat disorders

Introduction

The dairy cow is bred and fed to produce large volumes of milk. With the metabolic stress of high performance and the physical effects of being milked and handled two or three times daily, it is not surprising that the udder and teats are subject to a wide variety of disorders. The primary disease, mastitis, is of worldwide economic importance and much money is spent on its prevention, treatment and control. The first part of the chapter deals with mastitis in lactating and dry cows, and describes changes that may be seen in milk. The second part illustrates teat lesions, including a wide variety of viral infections, notably bovine herpes mammillitis, cowpox and pseudocowpox, vesicular stomatitis, and fibropapillomas (warts). Other systemic diseases that also affect the teats, e.g., foot-and-mouth disease, are covered elsewhere (p. 221).

Because of their anatomical position, especially in cows with pendulous udders, teats are vulnerable to injuries, eczema, and other physical influences. These problems are considered in the third part of this chapter, although changes associated with photosensitization are covered elsewhere (3.5). The final part of the chapter includes miscellaneous conditions of the udder.

Congenital conditions

Supernumerary teats

Clinical features

supernumerary teats are a congenital condition. They may be found between the front and rear teats, and/or attached to the udder behind the rear teats (11.1), or to the base or side of one of the main teats, where they can interfere with milking. They are typically, shorter than normal teats, and have thinner walls. They may connect to the sinus of an existing teat, or, more commonly, have a separate supernumerary gland.

Blind quarters

Clinical features

blind quarters in heifers with nonpatent teats can be either congenital or acquired. There are two congenital forms, one in which there is a total absence of the teat canal, but the teat fills with milk, and less commonly a second where there is a persistent membrane between the teat cistern and canal at the teat base, and no milk can be palpated in the teat. The acquired form, when a thickened central core is palpable in the teat canal, may be caused by undetected summer mastitis (11.2) or trauma from being suckled as a calf (2.14). The associated quarter may be swollen immediately postpartum due to accumulated milk, but this later regresses to be smaller than the other quarters. In mature cows a blind quarter may occasionally arise from chronic mastitis in the previous lactation, although in many animals a prolonged dry period often results in self-cure. Visible unevenness of quarters occurs in around 60% of milking animals, varying with age, stage of lactation, and mastitis history.

Mastitis

Summer mastitis

Clinical features

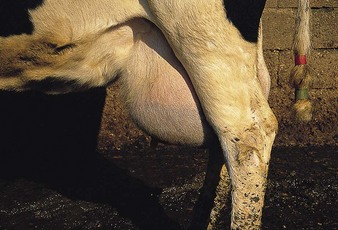

The Charolais heifer in 11.2 is an early case, showing distension of the left hind quarter, which was typically hard and sore, with a prominent, turgid teat. In more advanced cases, the infection may burst through the udder, as shown in the right hind quarter in 11.3. A thickening of the central teat canal was palpable, the quarter was very hard, and yellow pus with a pungent odor was discharging from the teat and udder.

Acute mastitis

Clinical features

the most prominent sign of acute mastitis is an enlarged, hard, hot and painful quarter, which may be apparent before any changes are visible in the milk. In some cases, a brown serous discharge may be seen on the surface of the affected quarter and teat, as in the lactating Friesian cow in 11.4. A section of an affected udder (11.5), shows deep red inflammation of the teat cistern and teat canal mucosa. There is prominent subcutaneous edema and the skin at the tip of the teat is congested. Changes of this nature can lead to gangrene. The yellow foci (A) in the udder parenchyma are pockets of pus. In 11.6 the teat of the affected quarter is swollen with areas of hemorrhage. There is an obvious area of gangrene affecting the udder skin, which is dry, cracked, and cold. This cow was severely ill with an eventually fatal toxemia, although in less extensive cases the necrotic portion of the udder will slough and recovery is still possible. Such cases should not be confused with udder bruising (11.7).

Advanced gangrene (11.8) leads to cold, damp teat skin. Although mastitis was limited to the left forequarter (A), the entire udder was blue, edematous, and cold to the touch. Adjacent to the affected teat is a skin slough and red exudate. The secretion from the udder was a deep port-wine color and was mixed with gas. The cow had been normal when milked 12 hours previously, indicating the peracute onset of disease. In cases of nonfatal, gangrenous mastitis the overlying skin (11.9), or even the entire affected quarter, sloughs slowly in 1–2 months.

Management

intramammary antibiotics, combined with parenteral antibiotics, fluid therapy and NSAIDs for more acute cases. Continual stripping of affected quarters, and parenteral oxytocin allegedly improves recovery rate. Prevention depends on reducing pathogen concentration at the teat orifice and correct machine function. Environmental hygiene, correct premilking teat preparation, avoidance of mechanical trauma to the teat sphincter (11.32, 11.33), and minimization of teat end impacts are all important points. Standard texts give details.

Chronic mastitis

Definition

Streptococcus agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae, S. uberis, staphylococci, Mycoplasma, Arcanobacterium pyogenes, and other bacteria can produce a chronic mastitis, manifested as “clots” in the milk (11.14), with or without palpable udder changes.

Clinical features

the Friesian cow in 11.10 has large, hard nodules protruding from the udder, with two in the right quarter and one in the left. These are chronic, intramammary, staphylococcal abscesses. Staphylococci were cultured from the milk, which had a high cell count and gave a strongly positive reaction to the California mastitis test. Such advanced cases, which are usually unresponsive to treatment, are dangerous carriers and should be culled. If only one quarter is affected, that quarter may be dried off otherwise infection will be transferred to other quarters and other cows at milking. The Friesian cow in 11.11 had a blind quarter, having had mastitis in the previous lactation. The front left teat is slightly smaller than the others, and the associated quarter has totally atrophied.

11.10 Chronic mastitis: large nodules are chronic staphylococcal abscesses within mammary parenchyma

Blood in milk

Clinical features

true blood clots are the characteristic feature of blood in milk. They may be present in slightly pink-tinged milk (11.12) or, in more severe cases, in a secretion that is almost totally red (11.13). Seen only in newly calved cows, or after trauma, the condition usually resolves spontaneously. Herd outbreaks of unknown etiology may occur.

Mastitic milk

Clinical features

watery, translucent milk with occasional clots (11.14) is typical of a mild mastitis such as that caused by S. agalactiae or S. dysgalactiae. Normal milk may be totally absent in severe staphylococcal (11.15) or Arcanobacterium pyogenes infections, when the secretion consists of thick clots suspended in a clear, serous fluid. Summer mastitis (often A. pyogenes) invariably produces a thick secretion with a characteristic pungent odor.

A light brown, serum-colored secretion is typical of Escherichia coli infection (11.16), while acute gangrenous mastitis (e.g., acute staphylococcal) may produce a red or brown homogenous secretion (11.17), often mixed with gas.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree