Ketosis Treatment in Lactating Dairy Cattle

Jessica L. Gordon, BS, DVM∗, Stephen J. LeBlanc, BSc, DVM, DVSc and Todd F. Duffield, DVM, DVSc, Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, 2509 Stewart Building (#45), Guelph, Ontario N1G2W1, Canada. E-mail address: jgordo04@uoguelph.ca ∗Corresponding author.

Keywords

Ketosis

Treatment

Systematic review

Propylene glycol

Introduction

Subclinical ketosis is a common disease of the transition period in dairy cattle, affecting approximately 40% of lactations in North America.1,2 The incidence on individual farms varies widely and may be as high as 80%.2 The costs associated with ketosis include treatment of the disease, increased risk and treatment of other diseases, decreased milk production, worse reproductive performance, and higher risk of culling in the first 30 days of lactation.3,4

Classification

Historically, ketosis was classified as primary or secondary based on when signs commenced and what concurrent diseases were facing the animal.5 Recently, this nomenclature has fallen out of favor, because most ketosis is seen in the first 10 days after calving in North America and may or may not be accompanied by other disease.1 The terms subclinical and clinical are favored for ketosis definition. Clinical ketosis is characterized by an increase in blood, urine, or milk ketone bodies in conjunction with other visible signs, such as inappetence, obvious rapid weight loss, and dry manure. Subclinical ketosis is defined as an increase in blood, urine, or milk ketone bodies, above a threshold shown to be associated with undesirable outcomes, in the absence of obvious clinical signs.

Because of the housing system used in many North American dairies (large groups of loose-housed cattle), it has become difficult or impossible to determine if a specific animal is showing clinical signs of ketosis. Attempts have been made to classify ketosis as clinical or subclinical based on blood β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) concentrations.3 However, our experience is that when examined, animals with high levels of ketonemia may show no clinical signs and animals with low levels may be obviously ill. The severity of clinical effect seems to depend on the individual animal’s ability to process and tolerate ketone bodies.5 The disease may therefore be best described as hyperketonemia rather than trying to distinguish clinical from subclinical.

Classification of ketosis is most relevant for clarity and consistency in comparing incidence risk rates. Depending on the methods and frequency of screening, incidence rates of clinical ketosis are expected to be 2% to 15% in the first month of lactation, whereas 40% cumulative incidence of subclinical ketosis is typical if cows are screened weekly during the same period.2 There is some evidence that greater ketonemia is associated with higher risk of negative outcomes, such as subsequent disease and culling.1 However, the importance of the distinction between clinical and subclinical ketosis with regard to treatment is unclear. To our knowledge, there are no well-designed studies that have shown a difference in efficacy of treatments based on the initial level of ketonemia.

Physiology of early lactation and ketosis

When considering effective treatment of ketosis, it is critical to consider the physiology of the animal during this period. At the beginning of lactation, animals are faced with a sudden and drastic increase in energy demand.5 This demand is coupled with a decrease in feed intake, which generally starts in the dry period. The rate of increase of feed intake post partum lags behind the demands of lactation, leading to a period of negative energy balance. Fat is mobilized from body stores in the form of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) to meet energy requirements. NEFA travel to the liver destined for 1 of 3 pathways, complete oxidation for energy, incomplete oxidation to ketone bodies, or re-esterification to fatty acids. All of these pathways are stimulated in the transition animal, but the magnitude of fat breakdown and tolerance of the individual determine the relative distribution of the paths.5

In early lactation, homeorhesis is the driving physiologic force.6 Homeorhesis was defined by Bauman and Currie as “the orchestrated or coordinated changes in metabolism of body tissues necessary to support a physiologic state.”7 These processes facilitate breakdown of body stores of fat and protein in excess of what would be allowed based on homeostatic regulation. This situation leads to a period of insulin resistance, which is nearly universal in early lactation animals.6 Milk production requires large amounts of glucose. Because ruminants absorb only minimal amounts of glucose from their diet, gluconeogenesis is required to meet this need. This process is generally diminished in animals affected by ketosis, leading to hypoglycemia. Providing glucose, stimulating gluconeogenesis, and decreasing fat breakdown form the foundation for rational ketosis treatment.8

Systematic review of ketosis treatment

Background

Reviews have long been used to summarize the body of literature on a given topic. This material can be especially helpful for practitioners who have limited time to read primary scientific articles or require the information in a short period while working on a clinical case.9 Historically, these reviews were narrative reviews conducted by an expert on the subject.10,11 Even high-quality reviews are inherently biased, because selection of papers and interpretation of the information are consciously or unconsciously influenced by the author’s opinions at the outset.

Systematic reviews help remove the bias of the reviewers by following a rigorous method in selection of materials to be included.9,11 Investigators provide a detailed framework for conducting the review that can be repeated and examined for accuracy. A specific question is formulated and an exhaustive search of the literature is performed. Methods for inclusion of materials are clearly defined and laid out before initiation of the review. The quality of all materials included is determined through specified criteria. Inclusion of all high-quality relevant material is the framework for a systematic review, so small studies that are well designed are not excluded because of lack of power.

Materials and Methods

A systematic review of ketosis treatment was performed in February 2011 to determine the most effective treatment(s) for ketosis in lactating dairy cattle. The search phrases “ketosis treatment cattle” and “acetonemia treatment cattle” were entered into 4 databases: CAB, PubMed, Agricola, and Google Scholar. These databases included references from 1900 to present in all languages. A complete list of references from the search was obtained from each database and abstracts were obtained for all references. Titles and abstracts were used to determine the relevance of each reference to the question. If abstracts were unavailable and the title was suggestive that the reference was relevant, the full reference was obtained and analyzed. Materials that seemed relevant based on the title or abstract were obtained in full and analyzed. In addition, a manual search of relevant conference proceedings (American Dairy Science Association, American Association of Bovine Practitioners) was conducted, and studies known to us that were not yet published in the peer-reviewed domain were solicited for evaluation.3,4,12

The following criteria were used to determine the appropriateness of materials for the review:

1. Study animals were lactating dairy cattle

2. Animals experienced naturally occurring ketosis

3. Animals were diagnosed before initiation of treatment and method of diagnosis was clearly defined

4. A control group was included that was positive for ketosis

5. Control group was untreated or treated with a baseline treatment common to both groups (eg, dextrose vs dextrose and insulin)

6. Any intervention was considered: oral, injectable, or feed additive

7. Any outcome was considered, but must be clearly defined: ketosis cure, health data, milk production, reproductive performance

Results of the Review

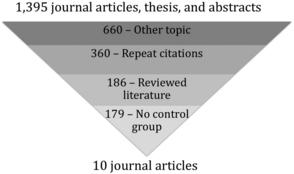

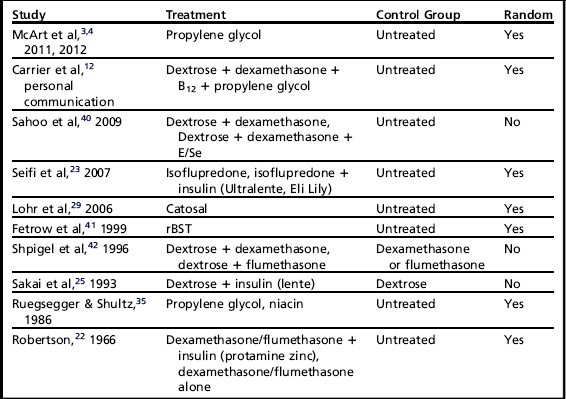

A total of 1395 references were obtained from the search (Fig. 1). These references included journal articles, theses, conference proceedings, abstracts, and book articles. Of these references, 660 were excluded because they covered another topic, such as ketosis prevention, and 360 were excluded as duplicate citations. A further 186 were excluded because they reviewed the literature without presenting novel data. Of the 189 that remained, 179 did not include a control group, leaving just 10 articles considered appropriate for the review (Table 1).

Table 1

Studies remaining after exclusion criteria were applied

Abbreviations: E/Se,Vitamin E/Selenium; rBST, recombinant bovine somatotropin.

One of the most striking aspects of this venture was the lack of well-designed ketosis treatment literature. During the past 15 years, the extent of ketosis observed in North America has been clearly defined and the prevalence of ketosis initially surprised many veterinarians and producers. Because of the relative frequency of clinical and subclinical ketosis, it is surprising that there has been so little advancement in the body of evidence for treatment of a ketotic cow. Much treatment of ketosis is based on disease principles or past experience. Although both of these factors are critical components for development of treatment strategies, stronger evidence is required to ensure rational and effective treatment.13 Because of the small number of studies that met the inclusion criteria and the large number of treatments represented by these studies, it is difficult to provide concrete information on many common treatments. However, some of the common treatments are discussed in relation to the findings of the review.

Dextrose

Background

The presence of hypoglycemia in ketosis was well established by the 1930s.14 Since that time, dextrose has been considered a staple in ketosis treatment. This treatment seems physiologically sound, because the requirement for glucose for milk production drives fat metabolism and hypoglycemia.8

There are concerns that the amount of glucose in a standard 500-mL bottle of 50% dextrose is excessive. A bolus of 500 mL 50% dextrose increases the blood glucose concentrations to about 8 times normal immediately after administration and returns to pretreatment concentrations by about 2 hours after administration.15 This increase is paired with an immediate 5-fold increase in circulating insulin concentration and a 12-fold increase after 15 minutes.15 Any glucose not used by the animal during this period is excreted via the kidneys, increasing the excretion of electrolytes and potentially increasing the risk of electrolyte imbalances.16 The decrease in blood BHB levels caused by dextrose treatment is short lived (<24 hours) and must be repeated or followed with another treatment for lasting effect.16

Some have expressed concern with the high level of glucose leading to abomasal dysfunction. There is evidence that high levels of glucose can lead to decreased abomasal motility, and displaced abomasum has been correlated with hyperglycemia.17–20 However, such effects of 1 treatment with dextrose have not been established.

Recommendations

Use of dextrose should be considered a second-line treatment of cases of ketosis. Animals with severe ketonemia with concurrent hypoglycemia may benefit from treatment with dextrose. Animals with ketosis suffering from nervous signs (such as abnormal licking, chewing on pipes or concrete, gait abnormalities, and aggression) should also be treated promptly with dextrose to alleviate hypoglycemia and nervous signs. These animals should then be followed up with other treatments for longer-term effectiveness.8,16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree