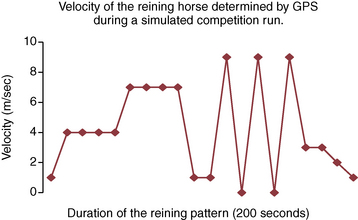

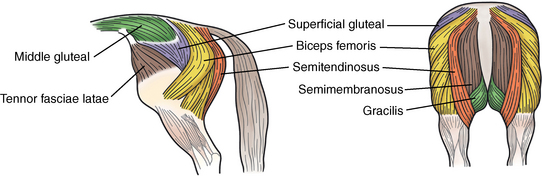

CHAPTER 26 For the context of this chapter, the working horse will be considered the performance horse bred and trained for the specific events of reining and cutting. Reining involves the horse and rider performing a specific pattern of movements, including galloping in small circles, flying lead changes, rapid spins of the forelimbs around a stationary hind limb, rapid accelerations followed by equally rapid decelerations, and sliding stops. Cutting requires that the horse, with little assistance from the rider, separates a steer from a herd and attempts to prevent the steer from returning to the herd. This requires a series of high-speed pursuits in time with the steer’s movements, with abrupt stops and turns, as well as an ability of the horse to predict stock movement and behavior (Figure 26-1). FIGURE 26-1 The cutting horse in action. (Copyright One Stylish Pepto Syndicate. Photo by Glenn Mandl.) As for the majority of equine athletic disciplines, the working horse is specifically bred over many generations to refine the ideal genetic characteristics suitable for the performance of tasks. The American Quarterhorse and, more recently, the Australian Stockhorse, are the main contributors to the specific genetic pool from which the working horse is drawn. The most successful working horses are typically of medium height (1450–1550 cm at the wither) (Scott, 2008). Quarterhorses possesses a high percentage (51%) of fast-twitch muscle fibers (Snow and Guy, 1980), suggesting that they have been selected for speed and power over a short distance. Conformation, particularly with respect to the spine, pelvis, hip, and tarsus, is an important selection factor, as the musculoskeletal injury rates in these regions are high (see summary of the working horse profile Table 26-1). TABLE 26–1 Summary of the Working Horse Profile The average duration of the working horse event is 2.5 to 3 minutes. Working horse competition represents intense, near maximal workload. The competition phase in combination with the preceding warmup results in mild lactate accumulation (mean plasma lactate levels 5.1 ± 1.9 millimoles per liter [mmol/L]) (Kastner et al., 1999), indicating that energy from anaerobic sources is being utilized. The reining competition covers a distance of approximately 680 m (mean average velocity 3.9 meters per second [m/s]) (Figure 26-2), and athletes reach heart rates of 181 ± 13 beats per minute (beats/min) (Kastner et al., 1999). At the end of the competition phase, horses are normally sweating and tachypnoeic, but recovery is rapid. Although the physiologic requirements of training and competition are only moderately intense in comparison with some other disciplines, the load on the musculoskeletal system is excessive. This is particularly so with regard to the immature age of the equine athletes subjected to such a rigorous training schedule. Because of limited preparation time and the necessity of the young horses to perform such complex motor patterns, the training schedule has limited allowance for recovery and physiologic adaptation. The working horse trains 6 days per week on most weeks from ages 18 to 24 months to competition at age 3 years. Figure 26-1 shows the extremely demanding musculoskeletal requirements of the cutting horse event. It is helpful at this stage to briefly analyze two of the important motor tasks performed by the working horse to understand the specific injury profile of the horse and the training requirements for good performance. The position depicted in Figure 26-1 is known as “getting into the ground” and is the pinnacle sign of the well-bred and well-trained cutting horse. The horse has just made a 10-m sprint across the deep sand arena shadowing the movements of a steer. The horse has rapidly come to a complete stop and is about to roll back to the left over its hocks in a 180-degree turn to sprint off in the opposite direction. The left hindlimb is the pivot limb for this turn and will support the majority of the horse’s (and rider’s) weight. Once the turn is initiated, the horse’s forelimbs will be totally unloaded and its front end will sweep around the planted left hindlimb and will not recontact the ground again until the 180-degree turn is completed. As the horse transfers its weight caudally over the hindlimbs, the weight of the horse and the weight of the rider are borne by the gluteal, tensor fascia latae, biceps femoris, sacrocaudalis dorsalis, sartorius, and adductor muscles of the horse, as the muscles stabilize the pelvis and hip, with the powerful biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus (hamstrings) muscles stabilizing the hip, stifle, and hock (see Figure 26-1; Figure 26-3). The gracilis is a large muscle in the working horse and is particularly important in breaking and exerting power in the crouched abducted position of the hips. The progression from eccentric (lengthening) to concentric (shortening) muscle contraction during this maneuver is very rapid and is the danger period for muscle tearing to occur. The hamstring muscles are particularly vulnerable during this period and are commonly injured in the working horse (Green et al., 2008). Once the weight of horse is accepted by the hindlimbs, the unloaded cranial skeleton begins to laterally flex, and the horse’s front end sweeps through a 180-degree rollback. Once the center of mass passes the line of the hip during the rollback, the pelvic and caudal limb prime mover muscles, in particular the gluteal and hamstring muscles, shift from an eccentric stabilizing role to a propulsive function, as the horse begins to accelerate out of the stop and turn in the opposite direction. This is a very demanding maneuver requiring great strength as well as agility. The role of the core stabilizing muscles to enhance dynamic stability, particularly in the lumbosacral spine and pelvis, during this type of maneuver should not be underestimated (see Figure 26-3) (Stubbs and Clayton, 2008).

Training working horses

Profile of the working horse

Breed

Quarterhorse/Australian Stockhorse

Age at starting training

18–24 months

Age at commencement of competition

3 years, rising 4 years

Muscle fiber type

51% fast twitch (Snow and Guy, 1980)

Conformation requirements

1450–1550 centimeters (cm) tall, sound, robust

Type of event

Near maximal, anaerobic (Kastner et al., 1999)

Duration of event

2.5–3 minutes

Distance of event

680 meters (Kastner et al., 1999)

Average velocity of event

3.9 meters per second (m/s) (Kastner et al., 1999)

Max heart rate of competition

181 beats per minute (beats/min) (Kastner et al., 1999)

Cardiovascular load

Moderate

Musculoskeletal load

High to extreme

Motor skill acquisition load

Extreme

Lateral preference (left/right handedness)

Bilateral, no preference

Injury rate/wastage

High

Industry standard training program

30 minutes, 6 times per week

Distance travelled in industry standard training session

2.06 kilometers (km)

Specific physiological requirements of training and competition

Musculoskeletal requirements

Stop and roll back

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Training working horses

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue