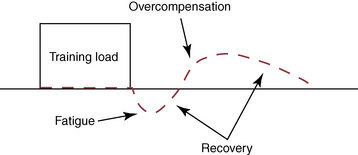

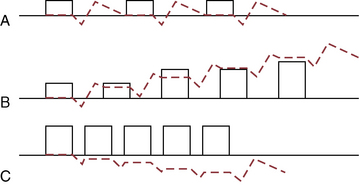

CHAPTER 21 The Standardbred horse, genetically, is a more superior athlete today than it was 15 to 20 years ago. It is more naturally gaited, possesses innate speed and intelligence, and has more human contact and handling from birth onward, making it easier to break and train. Standardbred horses in previous decades were more heavily boned and not as refined in their conformation. Trainers had to teach them to perform. Horses were more difficult to break and gait, and speed had to be developed. The stallion Meadow Skipper genetically changed the conformation of the horses he sired. Horses became more streamlined and taller, with higher withers, finer bones, and longer legs, thereby creating more speed. Speedy Crown and Speedy Somolli changed the trotting breed, making trotters more naturally athletic and better gaited. Contemporary Standardbreds have natural speed and, according to Kelvin Harrison, “fall out of their mothers pacing.” Today’s Standardbred trainer primarily develops and maintains fitness; all of the horses can “get up and go.” Modern trainers are conditioners, who attempt to ensure cardiovascular fitness and soundness. In the words of the veteran trainer Harry Harvey, “Horses don’t require as much savvy today to train. Our title has changed from trainers to conditioners.” During the preparation of this chapter, trainers were asked, “What makes a horse great?” Top trainers today are looking for class and speed. Horses may be able to pace a 1:49 mile and still not be able to win the race. A $100,000 claimer may be able to race just as fast as an Open horse, for instance, but still cannot beat that horse. Great horses are genetically made to have the physical aptitude and the mental aptitude to be champions. Great horses are extremely durable and tolerate stress well. The reality of training horses is that a perfect horse without weaknesses does not exist. A winning trainer has the ability to identify a horse’s weaknesses and then devise a plan to overcome them. A great horse must have innate courage to win races in spite of everyday aches and pains that would bother other horses (Eriksson, 1996). That being said, scientists and trainers need to evaluate what is now known about conditioning the Standardbred racehorse. At the 2006 International Conference on Equine Exercise Physiology (ICEEP), a workshop was held on workload and conditioning. Although the focus was on the Thoroughbred racehorse, lessons learned at the workshop have application to the Standardbred as well. It was proposed that workload could be quantified by using several selected parameters commonly recorded in the industry, such as velocity and distance, to produce a workload index. What needs to be asked is what can readily be modified with training, and how training programs can be tailored based on scientific methods with easy application for the field (Rogers et al., 2007). The most likely reason for the reluctance of horse trainers to adopt quantitative measurement of workload is the difficulty in identifying suitable field measurements. From a basic physiology standpoint, the respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems of the horse’s body are responsible for performance. Research indicates that maximum oxygen uptake ( FIGURE 21-1 Maximum oxygen uptake ( The metabolic demands of most equestrian disciplines are largely aerobic in nature. Conditioning programs should be designed to develop muscle properties that optimize stamina, speed, and strength. In Standardbreds, an improvement in both aerobic capacity and strength can be induced with training of low-to-moderate intensity (60%–80% Regardless of whether horse people are trainers or conditioners, they all need a basic understanding of exercise training and conditioning. An excellent overview of these concepts is presented in a 2007 review article titled, “Describing Workload and Scientific Information on Conditioning Horses” by Rogers et al. (2007). Their description of designing training programs based on scientific methods is discussed below. Single exercise bouts lead to fatigue and mild cellular damage, which, in turn, result in short-term adaptive responses (Figure 21-2). Performance capacity is not increased if rest periods between acute exercise bouts are too long or if training sessions are not sufficiently challenging (Figure 21-3, A). With regular and gradual increases in training, the adaptation that occurs during the recovery period of a single training session leads to overall improvement in performance (see Figure 21-3, B). Thus, trainers of harness horses must continually provide increased levels of stress to improve performance. This “overload” principle has been used for decades. The fine point is to know what the upper limit is for these adaptations and to be aware that each horse differs in its ability to cope with this stress. It is this trait that singles out the great horse trainers and conditioners. When training is too vigorous and rest periods too short, performance is reduced because of an imbalance between training stress and recovery (see Figure 21-3, C). Trainers need to consider the following when designing a horse’s training program: nature of the race; the current status of the horse’s level of fitness and past history; the total period available for training; and the training facilities and climate. Trainers can alter levels of stress by the type of exercise; the length of training program; and the intensity, duration, frequency and timing, and length of recovery periods (Rogers et al., 2007). Finally, the number of training sessions equates to the frequency of the application of stress to the horse. In high speed workouts or “training miles,” the horse’s muscle metabolism is 100 times more than at rest, and the increased oxygen consumption results in the formation of free radicals or oxidative stress (discussed later in this chapter); this causes muscle damage that lasts for 48 to 96 hours. Subjecting the horse to further hard work or speed miles during this period is likely to induce further damage and delay recovery (Rogers et al., 2007). All trainers interviewed agreed that it takes longer for horses to recover after a race today compared with 5 to 10 years ago. This is most likely caused by the current fast race times for the Standardbred racehorse. Like their Thoroughbred counterpart, the harness horse competing at the elite level needs more than a 1 week rest period to remain competitive, and its races need to be chosen with care to ensure ample recovery time between races. Although training methods have changed very little in the past decade, it is a fact that horses today are not trained as hard as they used to be and are trained with much less speed work. Trainers today build a base of fitness, increasing speed slowly. Horses are not scored down at fast speeds prior to a race nowadays. Generally, horses that are currently racing jog approximately four to five miles per day, train a trip 2 to 3 days out prior to the next start, race, and then have 1 day off. Horses should be jogged at a decent rate of speed (approximately 11–13 miles per hour or a 4:30–5:30 minute mile to ensure conditioning. For conversion from meters per second to miles per hour, see Table 21-1. Using the global positioning system (GPS) technology in place of a stopwatch should be considered by trainers to monitor speed and distance traveled. Training miles are performed at slower speeds than in the past, such as 26 miles per hour or a 2:20 minute mile. Hard last quarters are not performed anymore. TABLE 21–1 A decade ago, horses raced in multiple heats; with warmups and speed trips between heats. Similar to conditioning protocols, the warmup strategies of the harness horse before a race have changed as well. Today, a horse will have a low intensity warmup of approximately two miles prior to the race and then perform the actual race. Previous scientific work has shown that a warmup prior to intensive exercise such as a race accelerates O2 kinetics, augments aerobic energy metabolism, and reduces time to fatigue, hence the preference for the warmup (McCutcheon et al., 1999). Although the Thoroughbred and Standardbred perform a similar exercise test of work at maximal heart rate (HRmax) and maximal speed, at distances that take 1 to 3.5 minutes to complete, the trainers of these breeds utilized different warmup strategies in the past (Jansson, 2005). Trainers of Thoroughbred racehorses favored shorter, less strenuous warmups, whereas Standardbred trainers preferred several warmup heats. Today’s Standardbred trainer is warming up the horse less prior to a race and at a slower speed. A recent study in Sweden aimed to look at the advantage or disadvantage of a long warmup, especially as it related to time for recovery. Findings indicate that a short warmup, which would equate to one prerace warmup of one mile, approximately 1 hour before the race, would be most beneficial. With regard to the “score” before a race, it has been scientifically documented that a warmup prior to a race, including sprints, near maximal The second edition of the popular Care and Training of the Trotter and Pacer provides insight into breaking yearlings in the chapter by Charles Sylvester, and the text concurs with the trainers interviewed. Yearlings are line driven before being hitched to the jog cart, even though the sales preparation process has already had them used to human contact. Yearlings are started in a blind bridle with a latex-covered snaffle bit and a plain overcheck, or just a chin strap with a very long overcheck. Yearlings start jogging two miles for about a week, increasing to three miles a day after that. Horses are jogged both ways of the track to acclimate them to move and visualize their surroundings in both directions. Horses are jogged at a speed of 13 to 14 miles per hour (4:00- to 4:30-minute mile) to build up their condition and to keep them alert and focused. After 4 to 6 weeks of jogging three miles per day, a fourth jog mile is added, and horses begin doing training miles 2 days per week. The first time a young horse trains, it might go a 3:00 minute mile, or approximately 20 miles per hour. In subsequent weeks the trainer will bring the horse down 5 seconds for the mile each week until reaching a 2:40 minute mile, or speed of 22 miles per hour. After this point, the total time for the mile might remain at 2:40, but a focused effort should be made to ensure that the last half and quarter will be faster. If the horse can go a mile in 2:40 minutes with a half in 1:15 minutes and quarter in 35 seconds, it is ready to proceed. When a young horse has reached a 2:40 minute mile comfortably, it is ready to begin the second phase of training with repeating workout miles (Sylvester, 1996).

Training standardbred trotters and pacers

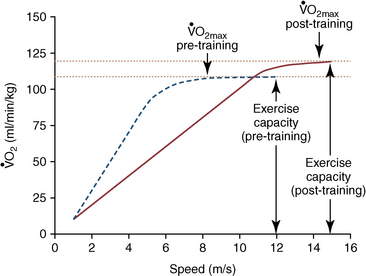

![]() O2max), continues to increase with training for several weeks to months (Rogers et al., 2007) (Figure 21-1). One would think, from this observation, that long jog miles or endurance training is more important in changing the horse’s aerobic performance than speed training (Tyler et al., 1998). More recently, however, it has been shown that speed training is a better choice for changing

O2max), continues to increase with training for several weeks to months (Rogers et al., 2007) (Figure 21-1). One would think, from this observation, that long jog miles or endurance training is more important in changing the horse’s aerobic performance than speed training (Tyler et al., 1998). More recently, however, it has been shown that speed training is a better choice for changing ![]() O2max. Other benefits of speed work are increased volume of blood being pumped per beat (stroke volume [SV]) and a lower heart rate for a specific blood flow rate (Evans et al., 1995). The heart and lungs are not the only organs that improve with training. Skeletal muscles and skeletal tissues such as bones, cartilage, and tendons also adapt to training. Muscles adapt to training by remodeling muscle fibers to increase aerobic capacity. Speed can also be improved with training by increasing the horse’s anaerobic capacity, but exercise at an intensity of 140% to 165%

O2max. Other benefits of speed work are increased volume of blood being pumped per beat (stroke volume [SV]) and a lower heart rate for a specific blood flow rate (Evans et al., 1995). The heart and lungs are not the only organs that improve with training. Skeletal muscles and skeletal tissues such as bones, cartilage, and tendons also adapt to training. Muscles adapt to training by remodeling muscle fibers to increase aerobic capacity. Speed can also be improved with training by increasing the horse’s anaerobic capacity, but exercise at an intensity of 140% to 165% ![]() O2max must be applied during the last phase of training (Rogers et al., 2007).

O2max must be applied during the last phase of training (Rogers et al., 2007).

![]() O2max) and exercise capacity are improved with training. Note that exercise intensity can continue to increase after

O2max) and exercise capacity are improved with training. Note that exercise intensity can continue to increase after ![]() O2max is reached. Exercise capacity represents maximum speed reached at the point of fatigue. (Adapted from Marlin D, Nankervis K: Training principles. In Equine exercise physiology, 2002, Figure 15.1, p 181.)

O2max is reached. Exercise capacity represents maximum speed reached at the point of fatigue. (Adapted from Marlin D, Nankervis K: Training principles. In Equine exercise physiology, 2002, Figure 15.1, p 181.)

![]() O2max) and relatively short sessions (6- to 12-minute duration) five times per week for 16 weeks. Prolonged training beyond this period with training at higher intensities (100%–110%

O2max) and relatively short sessions (6- to 12-minute duration) five times per week for 16 weeks. Prolonged training beyond this period with training at higher intensities (100%–110% ![]() O2max) increases aerobic capacity but does not improve muscle strength; instead, it reduces speed and simultaneously increases the risk of overreaching and overtraining (Tyler et al., 1998).

O2max) increases aerobic capacity but does not improve muscle strength; instead, it reduces speed and simultaneously increases the risk of overreaching and overtraining (Tyler et al., 1998).

Meters per Second

Miles per Hour

Approximate Mile Time (Minutes : Seconds)

1

2.237

26:49

2

4.474

13:25

3

6.711

8:57

4

8.948

6:42

5

11.185

5:22

6

13.422

4:28

7

15.659

3:50

8

17.895

3:21

9

20.132

2:59

10

22.369

2:41

11

24.606

2:26

12

26.843

2:14

13

29.080

2:04

14

31.317

1:55

15

33.554

1:47

![]() O2 does not improve total running time to fatigue compared with a lighter warmup (Jansson, 2005).

O2 does not improve total running time to fatigue compared with a lighter warmup (Jansson, 2005).

Breaking yearlings

Training standardbred trotters and pacers

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree