CHAPTER 2 The Skull

OVERVIEW

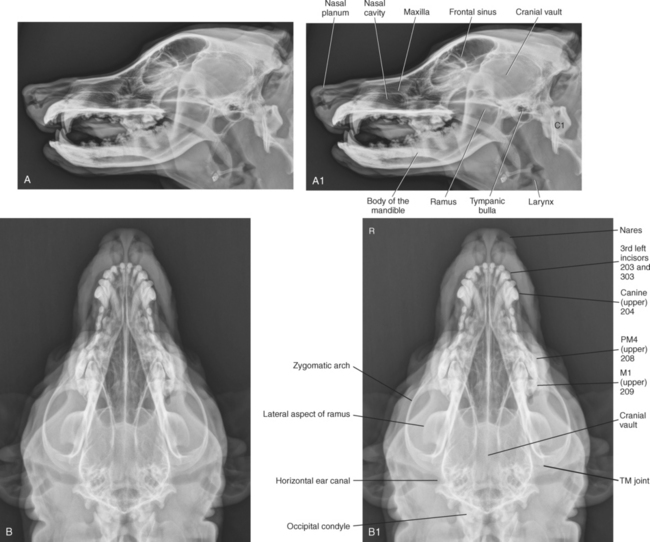

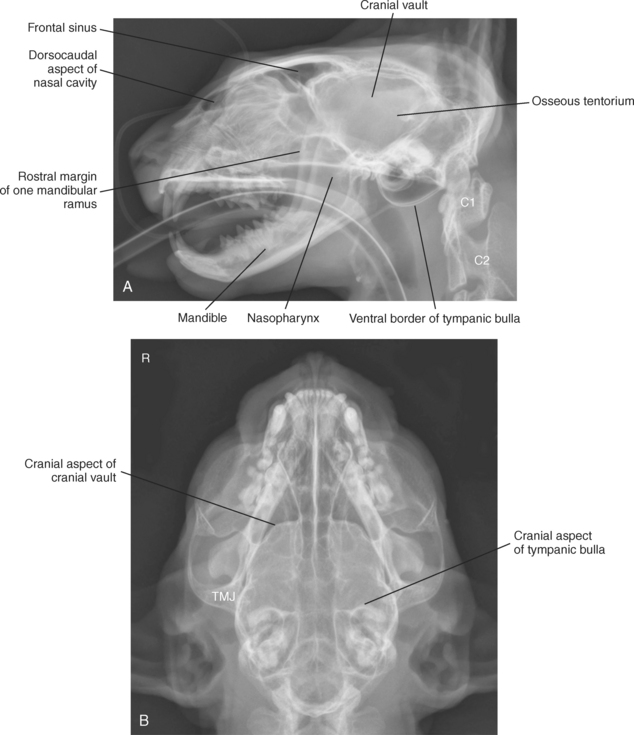

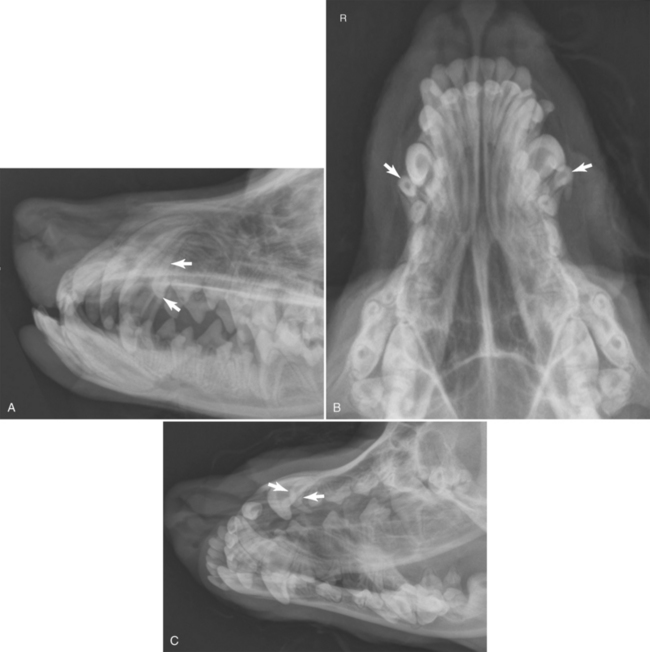

A radiographic study of the skull should always include a lateral and dorsoventral (or ventrodorsal) view (Figures 2-1 and 2-2).

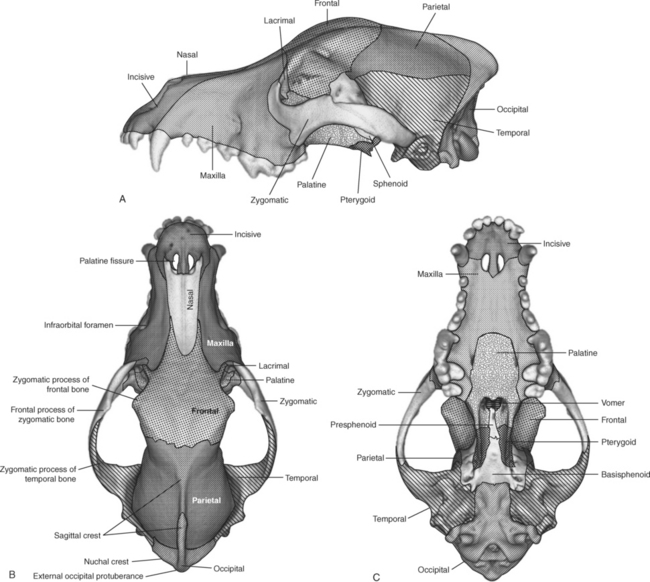

Approximately 50 bones, many of which are paired, compose the skull. Many are not identifiable with survey radiographs, and most fuse with adjoining bones precluding specific delineation. The important larger bones of the skull that are visible radiographically are the incisive, nasal, maxillary, lacrimal, frontal, zygomatic, pterygoid, sphenoid, parietal, temporal, and occipital bones. Figure 2-3 identifies these bones diagrammatically.

DENTITION

The upper incisors are located within the incisive bone, and the canine teeth, premolars, and molars are located within the maxilla bone (Figure 2-4). The maxilla is the large bone that, in addition to the much smaller incisive and nasal bones, encases the majority of the nasal cavity and the blind-ended maxillary recesses located ventrolaterally on each side of the nasal cavity. Ventrally, the maxilla forms the hard palate, which is the physical separation between the nasal and oral cavities. Caudally, the maxilla fuses with the frontal bone, which encompasses the frontal sinuses and the rostral aspect of the cranial vault.

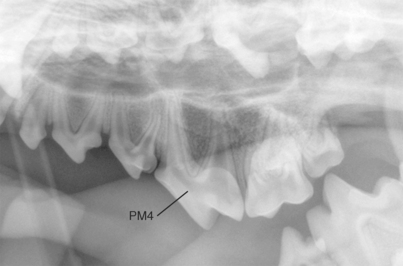

The fourth maxillary premolar and first mandibular molar in the dog are sometimes called carnassial teeth, which refers to their shearing functions. Canine tooth eruption times are given in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1 Canine Dental Eruption Times1

| Deciduous Teeth (Weeks) | Permanent Teeth (Months) | |

|---|---|---|

| Incisors | 3-4 | 3-5 |

| Canines | 3 | 4-6 |

| Premolars | 4-12 | 4-6 |

| Molars | n/a | 5-7 |

In the cat, the anatomic dental formulas are as follows:

In the cat, the roots of the upper fourth premolar extend into the wall of the orbit. The carnassial teeth in the cat are the same as in the dog: the last upper premolar and the first lower molar. Feline tooth eruption times are given in Table 2-2.

Table 2-2 Feline Dental Eruption Times1

| Deciduous Teeth (Weeks) | Permanent Teeth (Months) | |

|---|---|---|

| Incisors | 2-3 | 3-4 |

| Canines | 3-4 | 4-5 |

| Premolars | 3-6 | 4-6 |

| Molars | n/a | 4-5 |

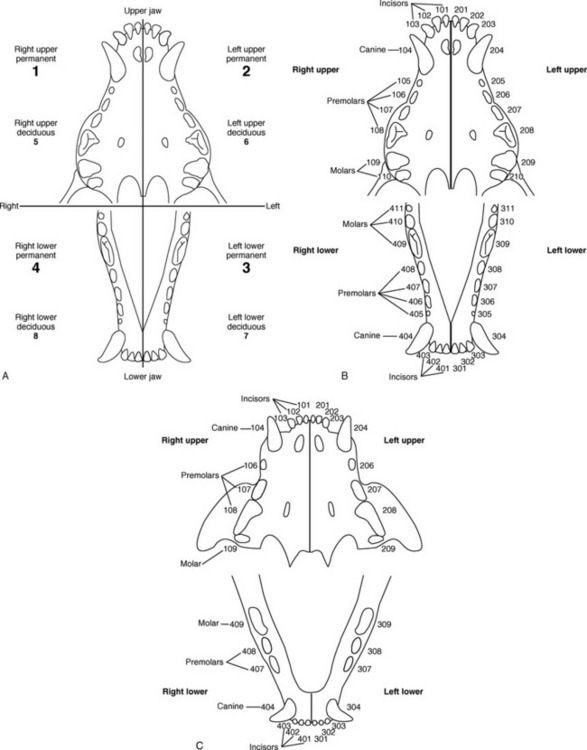

The modified Triadan system of dental nomenclature is an alternative system for tooth identification2 (Figure 2-5). The first digit denotes the quadrant. The right upper quadrant is designated 1, the left upper quadrant is designated 2, the left lower quadrant is designated 3, and the right lower quadrant is designated 4. The second and third digits denote positions within the quadrant, and numbering always begins at the midline; thus the central incisor is always 01, the canine is always 04, and the first molar is always 09. For example, the right upper fourth premolar would be tooth number 108 in the Triadan system.

Radiography of the dental arcade is commonly performed using dedicated dental x-ray machines, which generally have relatively low mA and kVp capabilities, used with intraoral film or a small dedicated intraoral dental imaging plate. In the absence of a dental radiographic system, lateral oblique views can be used to assess each dental arcade.

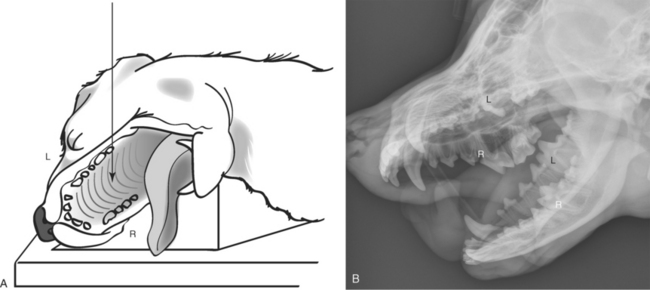

As previously noted, it is critical that labeling of oblique radiographs be accurate and that the radiographer understands what will be projected when the skull is angled. This has been described elsewhere,3 but a brief example follows. Assume the dog is in right lateral recumbency on the x-ray table and the goal is to evaluate the right upper arcade. By elevating the mandible with a nonradiopaque triangular sponge and using a vertical x-ray beam, the right maxillary arcade can be projected ventral relative to the rest of the maxilla without superimposition (Figure 2-6). To evaluate the right mandibular arcade, use the triangular sponge to elevate the maxilla, not the mandible. To evaluate the left arcades, reposition the dog in left recumbency and repeat the procedure.

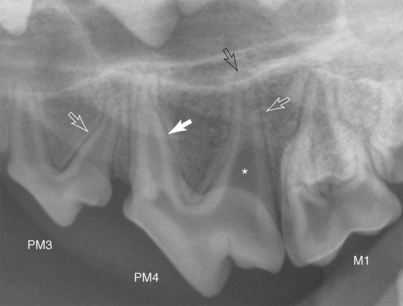

When a tooth is evaluated, the structures that can be visualized are the roots and crown, the pulp cavity, and the lamina dura. Although the periodontal membrane cannot be visualized directly, its location can be inferred (Figure 2-7).

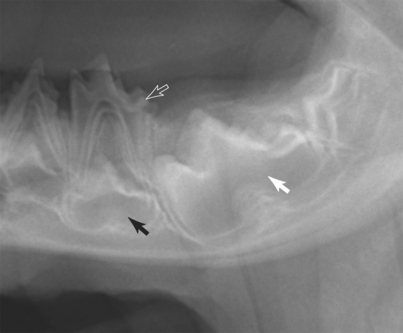

Visualization of both deciduous teeth and permanent teeth buds is normal in adolescent patients (Figure 2-8). Molars have no associated deciduous tooth. Normally, the deciduous teeth are shed as permanent teeth erupt. A retained deciduous tooth can impede eruption of permanent incisors, canines, or premolars. Alternatively, retained deciduous teeth may not impede eruption of the subjacent permanent tooth but become displaced as the permanent tooth erupts (Figure 2-9). Retained deciduous teeth are readily apparent upon visual inspection of the oral cavity. Radiographs are not needed for their detection but will be helpful in determining whether the eruption disorder is altering the underlying tooth roots or bone structure.

NASAL CAVITY AND SINUSES

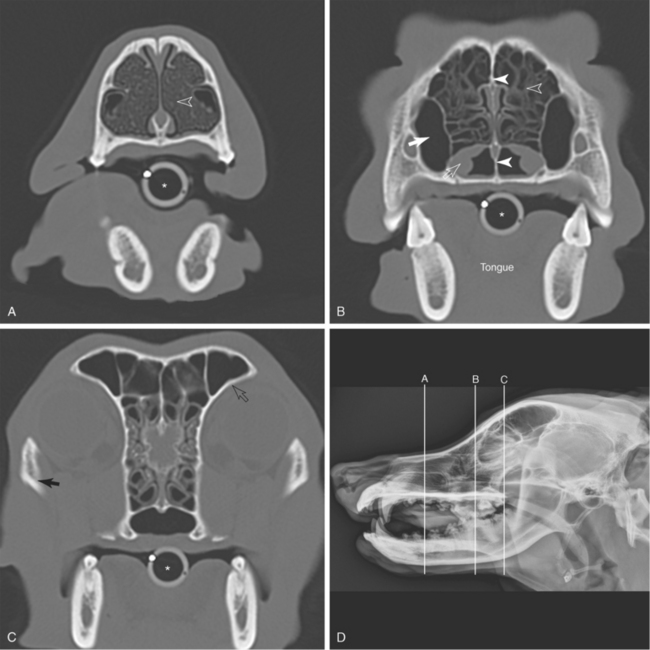

The nasal cavity is normally bilaterally symmetric, divided in the midsagittal plane by the vomer bone and nasal septum. Each nasal cavity contains a myriad of fine turbinate bones, collectively known as the ecto- and endoturbinates (Figure 2-10). These fine turbinates support the large mucosal surface area that is responsible for filtering, warming, and moisturizing inspired air. Standard views for the nasal cavity are lateral and dorsoventral views (see Figures 2-1 and 2-11), intraoral views with the film placed in the mouth, and oblique open mouth views. With analog (film-based) imaging systems, the best way to evaluate the nasal cavity is by using an intraoral film encased in a vinyl cassette system (3M Company, St Paul, Minn.) (Figure 2-12). By placing the film in the mouth and directing the x-ray beam onto the dorsal aspect of the maxilla, superimposition of the mandible is avoided. With digital systems, because the plate cannot be placed in the oral cavity, the best view to evaluate the nasal cavity is an open-mouth ventrodorsal oblique view (V20°R-DCdO). To acquire this view, the dog is anesthetized and placed in dorsal recumbency; the mouth is pulled open by placing tape or a small rope around the maxillary and mandibular incisors while maintaining a parallel relationship between the hard palate and x-ray table; the tongue is held against the mandible using mandibular gauze; and the x-ray beam is angled 20° rostrally and directed into the mouth. This eliminates superimposition due to the mandible but does result in some anatomic distortion (Figure 2-13).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree