Chapter 7 The cerebellum

Key points

The cerebellum receives subconscious proproprioceptive input from Golgi tendon organs and muscle spindles and the hair cells of the vestibular apparatus.

The cerebellum receives subconscious proproprioceptive input from Golgi tendon organs and muscle spindles and the hair cells of the vestibular apparatus.

It coordinates tone and movement of the head, body and limbs, by modulating activity of UMNs affecting agonist and antagonist muscles.

It coordinates tone and movement of the head, body and limbs, by modulating activity of UMNs affecting agonist and antagonist muscles.

It feeds back proprioceptive information to motor planning centres of the forebrain and is involved in setting the postural platform.

It feeds back proprioceptive information to motor planning centres of the forebrain and is involved in setting the postural platform.

The grey matter consists of a three-layered cortex (granule cells, Purkinje cells and molecular layer) and three pairs of deep cerebellar nuclei.

The grey matter consists of a three-layered cortex (granule cells, Purkinje cells and molecular layer) and three pairs of deep cerebellar nuclei.

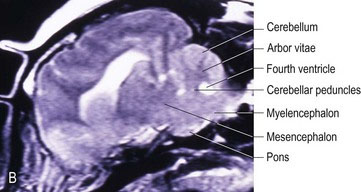

The white matter forms the arbor vitae and is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of cerebellar peduncles.

The white matter forms the arbor vitae and is connected to the brainstem by three pairs of cerebellar peduncles.

The ability of a neonatal animal to move correlates with the amount of cerebellar development at birth.

The ability of a neonatal animal to move correlates with the amount of cerebellar development at birth.

Deep cerebellar nuclei facilitate somatic UMNs and are inhibited by the only efferents from the cerebellar cortex, the gabaminergic Purkinje cells.

Deep cerebellar nuclei facilitate somatic UMNs and are inhibited by the only efferents from the cerebellar cortex, the gabaminergic Purkinje cells.

Spinocerebellar pathways, conveying subconscious proprioception, comprise two neurons, compared with the three-neuron pathway involved in conscious proprioception.

Spinocerebellar pathways, conveying subconscious proprioception, comprise two neurons, compared with the three-neuron pathway involved in conscious proprioception.

Clinical signs of cerebellar dysfunction may include ataxia, hypermetria, spasticity and tremor, but not paresis.

Clinical signs of cerebellar dysfunction may include ataxia, hypermetria, spasticity and tremor, but not paresis.

General anatomy

The cerebellum is sited in the caudal fossa of the neurocranium, and is separated from the cerebral hemispheres by the osseous tentorium and the tentorium cerebelli (see Fig. 3.11).

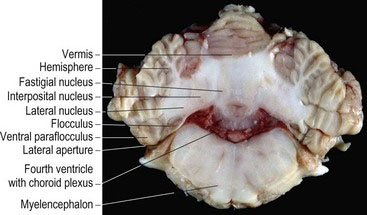

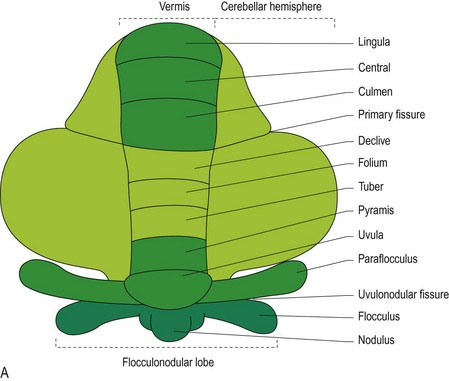

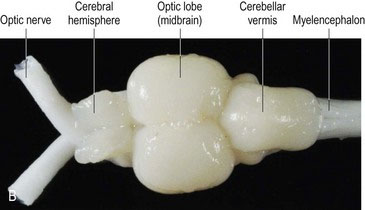

The cerebellum has a large body that is separated from the small ventral flocculonodular lobe by the uvulonodular fissure. The body of the cerebellum is divided into rostral and caudal lobes by the dorsally located, primary fissure. The flocculonodular lobe comprises a midline nodulus, on either side of which are small, paired lobules called flocculi. The flocculonodular lobe is also known as the vestibulocerebellum as it processes proprioceptive input from the vestibular system (Chapter 8). Dorsal to the flocculus on each side is the paraflocculus. The cerebellum is divided longitudinally into the midline vermis, with its nine lobules and the paired cerebellar hemispheres (Figs. 7.1, A8, A21–A24).

Fig. 7.1 Lobes of the cerebellum, dog brain, median section.

(Specimen courtesy of Mr. Allan Nutman, IVABS, Massey University.)

The surface of the cerebellum is corrugated by long, thin folds called folia. Folia are composed of both cortex and white matter and are separated from each other by sulci. The white matter that extends into each folium is called the white lamina of the folium, while the collective name for all the white matter is the arbor vitae (Latin = tree of life). It is named for its tree-like appearance on median section (Fig. 7.1).

The grey matter consists of the three-layered cerebellar cortex, which, from superficial to deep, are the molecular, Purkinje cell (cerebellar pyramidal cell) and granular layers. Grey matter is also deeply located at the base of the arbor vitae, forming the deep cerebellar nuclei. From lateral to medial these are the lateral (’dentate’ nucleus in humans), interposital and fastigial nuclei. Each nucleus receives input from the overlying cerebellar cortex. Hence the cortex of the hemisphere, the paravermis and vermis supply the lateral, interposital and fastigial nuclei, respectively (Figs. 7.2, A21, A22).

Cerebellar peduncles

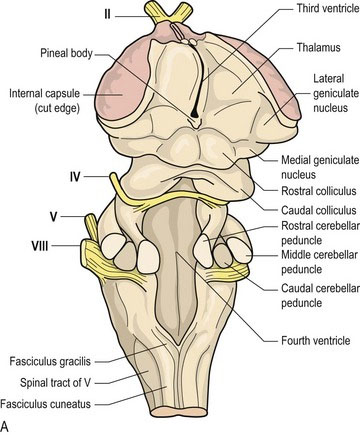

The caudal cerebellar peduncle has both afferent and efferent fibres. The afferent input includes the dorsal spinocerebellar, reticulocerebellar, olivocerebellar, cuneocerebellar and vestibulocerebellar tracts. Efferent fibres are located on the medial aspect of the peduncle and include cerebellovestibular and cerebelloreticular tracts, which connect to the medulla oblongata (Figs. 7.3A, B, A5, A20-23, A29, A30).

Evolutionary and functional anatomy

Phylogenetically, the cerebellum is divided into three longitudinal zones. Functionally, these regions coordinate muscles in different body regions (Fig. 7.4A).

1. Archicerebellum/vestibulocerebellum: This medial zone consists of the flocculonodular lobe and part of the uvula. It receives input from, and functions in conjunction with, the vestibular system to regulate equilibrium/balance and posture. This zone appeared first in fish.

2. Paleocerebellum/spinocerebellum: This intermediate zone comprises most of the vermis and the paraflocculus. It is where the major spinocerebellar afferent tracts terminate and coordinates truncal and limb movements. This zone appeared first in amphibians.

3. Neocerebellum/pontocerebellum: This lateral zone comprises the lateral hemispheres and caudodorsal vermis of the caudal lobe. It receives cerebral input via the pontine nuclei and regulates skilled movement.

Species differences

The size and shape of the cerebellum correlates with the type of movement and posture of the animal. Those animals with mainly trunk musculature and symmetrical limb movement (e.g. reptiles, fish and flightless birds) have a well-developed medial portion and small lateral hemispheres (Fig. 7.4B). Animals with well-developed limbs and independent limb movement have better developed lateral hemispheres, e.g. mammals and flying birds. Primates and humans, which have upright posture and complex, skilled limb movements, have highly developed lateral hemispheres and corticopontocerebellar systems. (The corticopontocerebellar system influences pyramidal tract function, which is also highly developed in these species.) Additionally, the lingula, the lobule of the vermis located just rostral to the nodulus, is well developed in animals with large tails (e.g. the rat compared with the pig) and the paraflocculus is bigger in animals with well-synchronised movements of the axial and appendicular musculature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree