15 The cancer patient with general lumps and bumps

A large number (if not the majority) of veterinary cancer patients present in general practice either because the owner has noticed a mass growing or because a mass is palpated by the veterinary surgeon during an examination. The variety of tumour types that are encountered in this way is significant, so it is very important that a logical and step-wise approach is taken in every case to ensure that a diagnosis is reached, if possible, before definitive surgery is attempted. If this is not undertaken for whatever reasons, making a definitive diagnosis postsurgery is essential. The general rule is that ‘if a mass warrants removal, it warrants knowing what it is!’ If the cost of histopathology really is a concern to the owner, at the very least the attending clinician should obtain representative tissue samples and store them in formalin for 2 years, so that if a mass recurs at or near the initial surgical site in the future, a diagnosis can hopefully still be reached before a second surgery is undertaken that may not be the most appropriate treatment when an adjunctive treatment may be better.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 15.1 – CUTANEOUS HISTIOCYTOMA IN A DOG

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Clinical examination

On examination he was very bright and alert. Dermatological examination revealed a firm, raised, reddened, dome-like lesion on the left cheek measuring 1.5 cm in diameter. The mass did not appear to be painful or to be causing him to be pruritic and there was no enlargement of the sub-mandibular lymph node (Fig. 15.1).

Theory refresher

Histiocytomas are benign tumours that are almost always seen on the skin of young dogs, especially between 1 and 2 years of age, although they can develop at any point in a dog’s life. In a recent UK survey of insured animals, canine cutaneous histiocytoma was the most common single tumour type reported, with a standardized incidence rate of 337 per 100 000 dogs per year. In other publications, histiocytomas account for approximately 12% of all skin tumours in the dog and are therefore considered to be common throughout the world but they are rarely seen in the cat. There appears to be no gender predisposition but Scottish terriers, boxers, dobermans, Labradors and cocker spaniels have been reported to have a higher incidence than other breeds. They usually present as solitary lesions, more commonly on the head and neck, but they can also very occasionally occur in multiple locations. They appear as raised, often erythematous, initially smooth, dome-like mass lesions that grow rapidly and they can become ulcerated. They are histologically fascinating, as under a microscope they often appear to a non-veterinary pathologist to be a high-grade, malignant neoplasm and yet they are benign and many, as in this case, will spontaneously regress. Fine needle aspiration therefore is always a sensible recommendation, as this is an easy cytological diagnosis and although many histiocytomas do require surgical excision, a large number can be treated conservatively without concern. If the mass is not ulcerated then recommending regular re-examination and no further treatment is usually best. However, if the mass becomes ulcerated, if the dog is troubled by the tumour, or if the cytology is uncertain then surgical excision is to be recommended. Surgical removal, when undertaken, is by simple cutaneous excision and routine closure. Cryosurgery has also been reported to give good results. The prognosis therefore for cutaneous histiocytomas is usually excellent.

Systemic histiocytosis is a variant on cutaneous histiocytosis, in which aggregations of benign proliferating histiocytes occur resulting in dermatological lesions as previously described but in systemic histiocytosis there is systemic involvement with nodular lesions developing in internal organs. It is therefore considered that systemic histiocytosis and cutaneous histiocytosis represent two different clinical manifestations of similar reactive proliferative dermal dendritic cells with different predilection sites and as such they are often grouped together as ‘reactive histiocytosis’. The reported target sites for systemic histiocytosis include the liver, the spleen, the lungs, lymph nodes, bone marrow and ocular tissues. Clinically the patients with this form of the disease are usually middle-aged and present with nodular or plaque-like skin lesions but with accompanying non-specific signs such as lethargy and inappetance. The clinical examination findings will vary depending on the organs affected. The diagnosis is made by histopathology. The clinical lesions can wax and wane but spontaneous recovery is not common, hence treatment with immuno suppressives is usually required. Interestingly, some studies suggest that the response of systemic histiocytosis to corticosteroids alone is variable but the response is more consistent using drugs such a cyclosporine and luflenomide.

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE 15.2 – MAST CELL TUMOUR IN A DOG

Case history

The relevant history in this case was:

Clinical examination

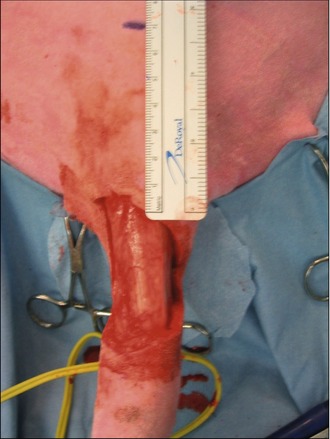

The tail was clipped and cleaned to reveal a large, raised ulcerated lesion as shown in Figure 15.2. No other masses were palpable and no other abnormalities were noted.

Treatment

In the light of the location of the tumour, surgical excision was thought to be the most appropriate first-line treatment with a view to submitting the mass for histopathology for grading. The mass was excised with lateral margins of 2 cm and a deep margin of one fascial plane, as shown in Figures 15.3 and 15.4.

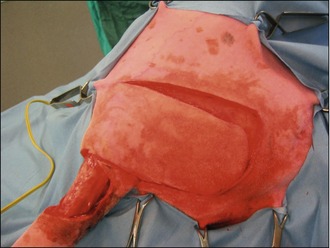

The deficit then required closure, which was achieved with a rotation flap, as shown in Figures 15.5–15.7. The reason a rotation flap was used is that this avoids tension at the surgical repair site which is especially important in an area of skin that is hard to immobilize. Attempting simple appositional closure at this site would have inevitably led to postoperative dehiscence and the need for more complicated reconstructive surgery.

Figure 15.6 Case 15.2 The skin flap is rotated into place to repair the tail wound and stapled routinely

Theory refresher

Mast cells are inflammatory leucocytes located within the dermis and subcutis that play an important role in allergic responses, wound healing and in acute and chronic inflammatory responses. As such, mast cells contain a number of different inflammatory mediators including histamine, heparin and the proteases tryptase and chymase which explains why some mast cell tumours cause a local inflammatory reaction around themselves and also why there is the potential for mast cell tumours to cause paraneoplastic problems such as gastric ulceration via parietal cell stimulation. Mast cell tumours (MCT) are common, being cited as the most frequently diagnosed cutaneous tumour of the dog and the second most frequently diagnosed cutaneous tumour in cats. In dogs, MCTs account for approximately 20% of all cutaneous tumours and there is a predilection for the disease in some breeds, such as boxers, bulldogs, Staffordshire bull terriers, Boston terriers, Rhodesian ridgebacks, pugs, weimaraners, Labrador retrievers, beagles and golden retrievers, thereby implying a genetic component to the aetiology of the disease. In cats, the Siamese seems over-represented in the incidence reports.

MCTs are a heterogeneous group of lesions, in that they have a variety of different presentations and that their behaviour can vary markedly from animal to animal and also from tumour to tumour. They can look like a well-circumscribed nodule that may or may not be erythematous or alopecic (Fig. 15.8). They can also arise from lesions that have been present for significantly long periods of time, initially appearing like a mass which should cause no concern for many months or even years. In addition, as well as solid cutaneous masses, MCTs can also present as soft, fluctuant subcutaneous lesions that may be initially misdiagnosed on palpation as a lipoma (Fig. 15.9). More aggressive MCTs, however, can develop rapidly into large, ulcerated, exudative lesions which may cause considerable morbidity for the patient.

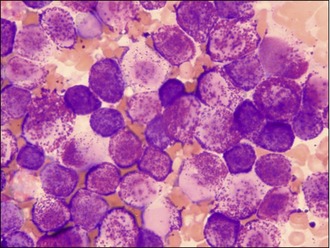

It is primarily because of this variation in appearance and the propensity of MCTs to mimic the appearance of other different cutaneous tumours that the authors have to recommend that all cutaneous masses undergo fine needle aspiration prior to any surgical excision being attempted. This argument is made stronger by the fact that mast cells are usually easily identified by cytology; MCTs often exfoliate large numbers of individual round cells that have round nuclei which often seem pale in appearance compared to the cytoplasm. The cytoplasm itself usually contains large numbers of granules that stain purple-red when using a Wright-Giemsa preparation and frequently the cells will have granules scattered in the space around them from other mast cells that were shattered in the process of obtaining the aspirate and forming the smears (see Fig. 15.10). Diff-Quick can be used and will also usually show the presence of the granules but sometimes Diff-Quick will not reveal the presence of the granules as well as a Giemsa stain, so it is recommended that Romanowski stains are used for this cytology whenever possible.

Once a MCT has been identified, all thoughts turn to treatment but it is important to remember that all MCTs have a metastatic potential and that whilst some will be essentially benign, some will be highly malignant and most fall somewhere between these two extremes. There is also some variation in behaviour between breeds; although boxers, bulldogs and pugs are very prone to developing MCTs they frequently behave less aggressively in these breeds. Overall, however, there have been many studies assessing the behaviour of MCTs and their response to treatment to establish the optimal way to approach this disease. One clear principle emerges: the best first-line treatment for MCTs is surgical excision if at all possible. Although there are difficulties and inconsistencies, both with the histological grading systems that are generally utilized and between different pathologists, it appears that well-differentiated tumours (grade I) are best managed by local excision alone and intermediately differentiated tumours (grade II) should be managed by local excision with 2-cm lateral margins and a deep margin of one facial plane. Whilst poorly differentiated, grade III tumours still require surgery as a first-line treatment, adjunctive therapy should usually be considered postoperatively but which adjunctive treatment to use is also subject to debate. The concern with grade III MCTs is that they have a higher metastasis rate and lower survival times after surgery alone when compared to dogs with grade I or II tumours so further treatment is sensible to help remove any metastasizing cells or secondary tumours. The problem comes in that no large scale studies have been published to indicate which is the most effective chemotherapeutic approach to take in these cases. However, there are three approaches the medical author (RF) usually uses in cases that require chemotherapy:

The clinical approach to MCT cases, therefore, must be to firstly make an accurate diagnosis using cytology whenever possible and the authors highly recommend undertaking fine needle aspirates of any cutaneous mass before considering surgical excision in an attempt to establish the diagnosis. Once this has been done, the draining lymph nodes must be carefully palpated and if enlarged, they must be aspirated too. Abdominal ultrasound should be undertaken, as if there is a malignant potential for the tumour then secondary disease in the abdominal lymph nodes, liver or spleen is possible and this should be assessed before the primary tumour is excised. Pulmonary metastasis with MCTs is very unusual but thoracic radiographs should be considered as well. If there are considerable cost restrictions, as the majority of cases will be grade I and II with a lower metastatic potential than a grade III tumour, it is not unreasonable to simply undertake a good surgical excision once the aspirates have confirmed the mass to be an MCT (2-cm lateral margins and one fascial plane deep if possible) and submit the tissue for histopathology. The exceptions to this are MCTs found on the subungual area (the nail bed) and on mucocutaneous junctions, as tumours in these regions frequently behave aggressively and full staging before surgery is necessary. If after the histopathology the tumour is shown to be grade III, then postoperative staging is also essential.

FELINE MAST CELL TUMOURS

The majority of cats with cutaneous MCT develop the mastocytic variety and in particular, a subtype known as ‘compact mastocytic MCT’. These tumours generally behave in a relatively benign manner, growing locally but showing little metastatic potential. There is a second subtype of mastocytic MCTs called a ‘diffuse mastocytic MCT’ and these tumours do show relatively more aggressive behaviour with an increased likelihood of local recurrence following excision and an increased risk of causing metastatic disease. However, pleasingly, they are not as common as the compact mastocytic form (accounting for up to only approximately 15% of cases of mastocytic MCTs). Histiocytic cutaneous MCTs are generally considered to exhibit benign behaviour with many being reported to spontaneously regress, although this can take up to 2 years. Histiocytic MCTs occur most frequently in young cats (less than 4 years old). Siamese cats may be pre-disposed to this form, whilst the more common mastocytic form is most commonly seen in middle-aged animals (average age of 9 years old) with no breed or gender predilection. The mastocytic MCTs usually present as solitary, firm, round, well-circumscribed, variably sized masses (0.5–3.0 cm in diameter) that are dermoepidermal or subcutaneous in origin, whereas the histiocytic MCTs usually present as multiple, raised, firm, round, well-demarcated papules and nodules that are generally small (0.2–1.0 cm in diameter). It is important to note that it is also possible to see multiple mastocytic MCTs, so the presence of multiple lesions does not necessarily imply a diagnosis of the histiocytic form of the disease.

When a patient presents with a suspected visceral MCT, the diagnosis is still relatively easy to obtain. A detailed abdominal ultrasound will be required, but aspiration of an intestinal or splenic mass is possible and advisable. A middle-aged to older, vomiting or inappetant cat presenting with obvious splenomegaly that appears heterogeneous on ultrasound is highly suspicious for a splenic tumour, so aspiration may not be necessary as splenectomy is indicated anyway. If surgery is planned, it is highly advisable to undertake a detailed abdominal ultrasound pre-operatively to assess for metastatic disease within the draining lymphatics (the mesenteric nodes, or the gastrosplenic nodes depending on the site of the primary tumour) and the liver and also to undertake left and right lateral inflated thoracic radiographs. It has been estimated that up to 30% of cats with splenic MCT will have either peritoneal or pleural effusions, so if identified these need to be aspirated and assessed for malignancy before surgery is performed. Cats with intestinal MCT can usually be considered to have a poor prognosis, due to the high incidence of metastatic disease but if there are no metastatic lesions found then undertaking excision is still recommended. Surgery must aim to remove at least 5 cm of intestine either side of the tumour, as it has been shown that the tumour frequently extends beyond the visible margins.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree