Chapter 4 Surgical Considerations

4.1 Preoperative Preparation

Evaluation of the Patient

All animals that are surgical candidates should have a complete physical examination, including auscultation of the heart and lungs and an assessment of the surgical problem. For simple elective surgical procedures in young healthy animals, preoperative laboratory work is probably not necessary. Laboratory screening is of value for animals that undergo general anesthesia, those with a more complicated disorder, and those with significant potential hemodynamic complications associated with surgery (such as blood loss). Packed cell volume (PCV) and total protein (TP) are screening tests easily performed that may influence preanesthesia preparation and intraoperative response to blood loss. For cattle with complicated gastrointestinal disturbances, such as an abomasal volvulus, plasma electrolyte concentrations help determine appropriate replacement fluid therapy (see Chapter 5). A complete blood count would help identify animals affected with serious infectious processes and may influence preparation and the timing of surgery. If other systemic concerns about a farm animal, such as fatty liver syndrome in a cow, exist, specific tests such as a serum GGT can be run, or if finances permit, a large animal biochemical panel may be more appropriate.

Cattle that undergo elective surgical procedures under general anesthesia in lateral or dorsal recumbency should be fasted 24 to 48 hours before surgery to decrease the ruminal content and ruminal distension and risk of aspiration pneumonia. Furthermore, in ruminants subjected to general anesthesia, fasting is essential to improve venous return and ventilatory capacity (see Chapter 6).

Patient Positioning

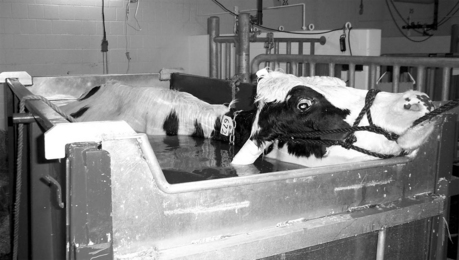

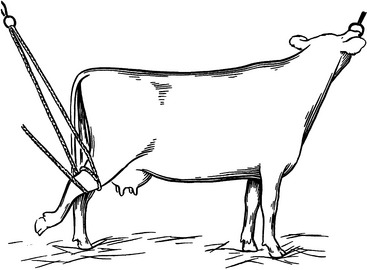

Determining the appropriate incision site is half the battle in gastrointestinal surgery in dairy cattle. Fortunately, the placid nature of the dairy cow permits many procedures to be done on a standing animal using a local anesthetic. For a more fractious animal, it may be possible to use small amounts of sedation, but this should be used with caution because it increases the risk that the animal will become recumbent. Lateral recumbency can be used for flank and inguinal approaches. Dorsal recumbency may be used for teat surgery, access to the cranial abdomen, and cesarean sections. Padding of bony prominences is indicated in recumbent procedures. For animals placed in left lateral recumbency, placing an inner tube or other pads under the shoulder and hip of a cow has been suggested as useful in making a so-called “sling” for the rumen (Figure 4.1-1). Rarely have we had to place animals in sternal recumbency, either for nasal or cervical surgery (Figure 4.1-2). Other acceptable padding includes air mattresses, water beds, foam pads, and inflatable surgery tables (Snell tables*).

Preparation of the Surgeon

Gloves should be worn for all surgical procedures. This helps avoid contamination from the residual flora on the surgeon’s hands. Gloves also protect the surgeon from any allergens or contact dermatitis. Most gloves are made of latex and come in a single-use package in a wide variety of sizes. Hypoallergenic vinyl gloves are available for those with latex sensitivity. Magnesium silicate powder is preapplied to most gloves to make them easier to don; therefore gloves should be rinsed before handling tissues. Gloves commonly develop holes and should be checked often for defects. Double gloving is used if extensive draping is required or contamination of the surgeon’s hands by sharp objects such as bony fragments and orthopedic implants is likely. Gloves can be applied with a closed or open gloving technique. Closed gloving techniques are preferred because the surgeon’s skin will not make contact with the outside of the gown cuff. An open gloving is recommended to replace a glove during a procedure. Otherwise, the cuff of the gown that has been exposed to skin and perspiration will be pulled over “clean” hands. Cuffs of the surgeon’s gown should be covered completely by gloves because the cuff material is not impervious to water penetration. Water often finds its way to the surgeon’s hands regardless of the material chosen; therefore plastic safety sleeves and double gloving are often helpful during procedures in which the surgeon’s hands and arms may be submerged. Although a gown is sterile when first applied, it should be remembered that only the front, above the waist, is considered sterile during the procedure.

Draping the Surgical Field

If long enough, the tails of adult cows should be tied—usually to one hind leg—for standing procedures. Large disposable laparotomy cloths or disposable drapes are available.* They may be fenestrated, or an appropriate-sized hole can be made by the surgeon. They are usually used alone and secured in place with penetrating towel clamps. Although they are relatively expensive, they are a great help in allowing the surgeon to focus on the procedure without worrying about contamination from dirt, fecal material, or body fluids.

Prevention of Peritonitis and Surgical Infection

PRECONTAMINATION

The optimum time to intervene in the development of a surgical infection is before a known or anticipated episode of contamination. Careful planning of the procedure will minimize the period of contamination, ensure adequate restraint, and minimize the use of potential adjuvants to reduce the risk of infection. Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered in planning any clean-contaminated or contaminated procedure and clean procedures in patients with identified risk factors. Common patient risk factors include preexisting nonbacterial inflammatory peritonitis, malnutrition, circulatory shock, and remote or systemic infection. In the latter case, elective procedures should be delayed until the preexisting infection can be treated and resolved. Similar steps should be considered when facilities, the animal’s behavior, or its condition increase the risk of contamination (see Section 4.7). Field conditions often involve less than optimal restraint facilities, fractious animals, limited control of external sources of contamination, and conditions that might predispose to unexpected recumbency during standing procedures (hypocalcemia, exhaustion, extreme peritoneal tension), all of which increase morbidity.

CONTAMINATION

Preventive measures are similar to those described for the precontamination stage, with a few additions. Prophylactic antibiotics can still be of some benefit, but they should be given intravenously to achieve high serum and tissue levels as soon as possible. If a source of contamination first develops intraoperatively, rapid steps to minimize the amount and distribution of contamination are indicated. For example, in gastrointestinal surgery, gross contamination should be localized whenever possible by exteriorizing the site of leakage or isolating it with laparotomy sponges; physically removing all accessible contaminants; and avoiding palpation unless absolutely necessary so that contaminants are not physically transported from the site of leakage to other sites in the abdomen. If the site can be adequately exteriorized to allow external drainage, localized lavage with a sterile isotonic fluid can help remove contaminants. However, generalized lavage is more likely to distribute high concentrations of organisms to potentially clean areas and is only recommended if the site cannot be exteriorized or dissemination has already occurred. Adding antibiotics to the lavage fluid may be indicated even if appropriate systemic antibiotics have been administered.

Other important considerations in the after care of the surgical farm animal are supplying adequate hydration (see Chapter 5), keeping neonates warm, and providing adequate nutrition and oral electrolytes.

Down cattle need excellent footing that keeps them from slipping. They need to be supported by having food and water where it can be reached. Good padding in a heavily bedded stall or on soft dirt is ideal. If cattle remain down for prolonged periods of time it may be necessary to try to get them up with well-padded hip lifts. Alternatively, cattle can be “floated” in a commercial tub (“Aqua cow”)* (Figure 4.1-3). This apparatus requires a fair amount of time, patience, and manpower. Regardless it has been successful in the right hands for recumbent cows that are amenable to therapy.

St. Jean G. Decision making in bovine abdominal surgery. Vet Clin NA, Food Animal Practice, Surgery of the Bovine Digestive Tract. 1990;6:335-354.

Stone WC. Preparation for surgery. In Auer JA, Stick JA, editors: Equine surgery, ed 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999.

Turner AS, McIlwraith CW. Presurgical considerations. In Turner AS, McIlwraith CW, editors: Techniques in large animal surgery, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1996.

4.2 Perioperative Antimicrobials and Analgesics

If an enterotomy is performed, broad-spectrum coverage may be required. A therapy that combines penicillin and ceftiofur (both at 2 to 3 times label dosage) often is used. In a hospital setting, intravenously (IV) administered penicillin salts (22,000 units/kg) are sometimes substituted for procaine penicillin to achieve higher tissue concentrations, but more frequent administration (q6h) is required. If a venous catheter is used for penicillin salt administration, the water-soluble form of ceftiofur can also be given by this route. Ceftiofur IV administration causes less tissue irritation and discomfort with high peak serum and tissue levels of the parent drug. Using the water soluble form of ceftiofur IV is acceptable because it achieves plasma and tissue levels of the parent drug; and its metabolite, desfuroylceftiofur, exceeds the MIC of many gram-negative organisms of veterinary importance, as does its IM or subcutaneous (SQ) use. The SQ administration has the advantage of preserving beef quality because less muscle irritation occurs in comparison to that associated with an IM injection. Another option is oxytetracycline use, a broadspectrum antibiotic that is moderately effective against gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic organisms. It is occasionally used at an extra-label frequency (6.6 to 11 mg/kg q12 h) to maintain higher tissue levels. Tetracycline is more lipid-soluble than either penicillin or ceftiofur; therefore higher tissue concentrations would be expected. Tetracycline disadvantages are its bacteriostatic activity and potential for causing renal failure when administered at high daily dosages and/or to dehydrated animals. At present, Liquamycin LA-200 is the only form of oxytetracycline with a label that allows use in lactating dairy cattle. Used at the label dose (6.6 to 11 mg/kg IV, SQ, or IM q 24 hr), the drug has a 28-day meat withdrawal and 4-day milk withdrawal.

Florifenicol (nonlactating cows), enrofloxacin (beef cattle with respiratory disease only), and tetracyclines are occasionally used as perioperative antibiotics. Aminoglycosides combined with penicillin, ampicillin, or Ticarcillin/clavulanate are rarely used in calves—and then only with strict adherence to extra label use (Table 4.2-1). Antibiotics prohibited under all circumstances in food animals are given in Box 4.2-1.

TABLE 4.2-1 Combination Use of Antimicrobial Drugs in Farm Animal Surgerya,b

| NONANTAGONISTIC | ANTAGONISTIC |

|---|---|

| Penicillin and aminoglycoside | Penicillin and tetracycline |

| Ampicillin and aminoglycoside | |

| Amoxicillin and aminoglycoside | |

| Cephalosporin and aminoglycoside | |

| Erythromycin and rifampin* | |

| Trimethoprim and sulfonamide (TMP/S)* | |

| TMP/S* and rifampin* | |

| Sulfonamide and tetracycline | |

| Lincomycin and spectinomycin | |

| Enrofloxacin† |

† Beef cattle for respiratory complications only.

a The American Association of Bovine Practitioners, in being cognizant of food safety issues and concerns, encourages its members to refrain from the intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intravenous extra-label use of the aminoglycoside class of antibiotics in bovines (Approved by the Board of Directors, December 1994).

b Until further scientific information becomes available, aminoglycoside antibiotics should not be used in cattle except as specifically approved by the FDA (Approved by the American Veterinary Medical Association House of Delegates, 1998).

BOX 4.2-1 ANTIMICROBIAL DRUGS PROHIBITED FOR USE IN FOOD ANIMALS

Perioperative Analgesics

Perioperative analgesics are indicated in most surgical procedures to temper the initial inflammatory response and decrease swelling as well as to improve the appetite and general well-being of the patient. In cattle with routine, relatively nontraumatic surgery (e.g., omentopexy), perioperative analgesics commonly are not used simply because of cost and loss of product value as a result of milk withholding. This is particularly true if cattle are being treated perioperatively with ceftiofur, which has no withholding time. The most commonly used antiinflammatory drug is flunixin meglumine (1.1 mg/kg IV or IM). Flunixin is a cyclooxygenase inhibitor that provides excellent analgesia, including visceral analgesia, and is the only FDA-approved nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug for cattle—albeit only for beef cattle and only IV. It may be indicated during the time of routine (one or more dosages) bovine surgery and in the immediate postoperative period when withholding times for milk and meat are not a major issue (when used only preoperatively at label dose, it incurs 10 days of meat withholding and 3 days of milk withholding).

Xylazine epidurals (0.05 mg/kg) or Medetomidine 5 to 15 μg/kg may provide slightly better analgesic effects than lidocaine. Xylazine 0.03 mg/kg can be combined with lidocaine (0.2 mg/kg) for both fast-acting and long-lasting (4 to 5 hours) analgesia. Butorphanol may also be used intramuscularly or intravenously (0.1 mg/kg) for severe pain that cannot be adequately diminished with NSAID therapy. For information regarding the use of nonapproved antibiotics and analgesics, the reader is encouraged to consult Food Animal Residue Avoidance Data Bank at www.farad.org.

Brown SA, Robb EJ. Plasma disposition of ceftiofur and metabolites after intravenous and intramuscular administration of ceftiofur sodium to calves of various ages. The Bovine Proceedings. 1995;27:206-207.

Extra-label drug use in animals: final rule. Fed Reg. 1996;61:57732-57746.

Gingerich AG, et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosage of aspirin in cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1975;167:945-948.

Okker H, et al. Pharmacokinetics of ceftiofur in plasma and uterine secretions and tissues after subcutaneous postpartum administration in lactating dairy cows. J Vet Pharmacol Therap. 2002;25:33-38.

Payne MA. Extra-label drug use and withdrawal times in dairy cattle. Comp Cont Educ Pract Vet. 1991;13:1341-1351.

Payne M. Antiinflammatory therapy in dairy cattle: therapeutic and regulatory considerations. Calif Vet. March 10-12, 2001.

Riviere JE, et al. Primer on estimating withdrawal times after extra-label drug use. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213:966-968.

Salmon SA, et al. In vitro activity of ceftiofur and its primary metabolite, desfuroylceftiofur, against organisms of veterinary importance. J Vet Diag Invest. 1996;8:332-336.

4.3 Facilities and Restraining Devices

Introduction

When working with livestock, one faces inherent risks to the safety of the animal and handler. Livestock, by their sheer size, are a threat to human safety. Fearful or aggressive animals with horns are exponentially more dangerous and can inflict significant injury—or even death. Bulls are always dangerous and unpredictable and should never be trusted. Dairy bulls, because of their extensive human contact, lack a natural fear of humans and may be overtly aggressive. Beef bulls generally react out of fear toward humans. The protective, maternal instinct of a cow with a calf makes them significantly more dangerous then a single cow. Because beef cows usually are not intensively handled, they are more dangerous than dairy cows. It has been suggested that the position of the hair whorl between a cow’s eyes correlates with the degree of agitation the cow demonstrates under restraint. Animals with whorls located high on the forehead, above the level of the eyes, were found to be more aggressive under restraint (high whorls, hot-headed) (Grandin, 1995).

Knots

SQUARE KNOT

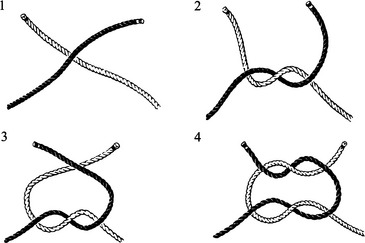

The square knot joins two rope ends. Joining the ends of a single rope forms a loop that allows the rope to be tied to a fixed object. Alternatively, the ends of two separate ropes can be joined to form one long rope. Once tightened, a properly tied square knot will not slip under tension. A common error is to tie a “granny knot” that slips when tension is applied (Figure 4.3-1).

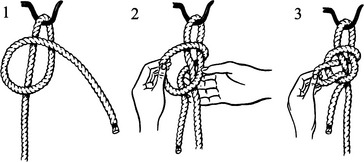

QUICK-RELEASE SLIP KNOT

The quick-release slip knot and its modifications (see Tail Ties) secure the rope but allow it to be easily untied. For example, the free end of a halter may be tied to a post to restrain an animal’s head. When properly tied, the bow end of the knot is entirely surrounded by rope; if the bow lies against the object to which it is tied, it is not secure and will loosen as the animal struggles. Because it is a slipknot, there will always be a little play in the rope as it slips down to its anchor; tying the knot as close to the anchor as possible is important (Figure 4.3-2).

Restraint of Cattle

MOVING CATTLE

Moving Animals by Halter

If an animal is reluctant to proceed, the handler should make sure advancement is not impeded and no one is standing in the animal’s path or line of vision. When encouragement is required, one should again start with the least noxious prodding necessary to stimulate the animal to move—a slap on the rump or a prod along the backbone with a blunt object. Although the discomfort from a tail twist is often effective, it holds potential for breaking a coccygeal vertebra. The electric prod should be used only as a last resort. Shouting should be discouraged because it increases confusion, stress levels, and impatience.

KICKING

Flanking

A manual method to deter an animal from kicking is called “flanking.” The fold of skin in the flank is lifted, and the handler places a thigh against the animal’s stifle. This provides mechanical resistance that interferes with the animal’s ability to kick. A mechanical device working under the same premises lifts against the flank and attaches over the back beneath the lumbar vertebral processes.

SURGICAL POSITION

Casting

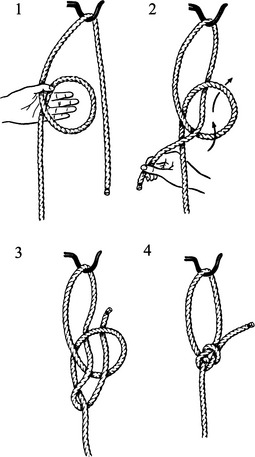

Casting is a technique used to force an animal to lie down (Figure 4.3-4). A loop of rope is placed around the animal’s neck with a bowline knot or a quick-release honda. Some people prefer to run the loop over the neck and between the front legs to prevent undue pressure on the trachea. Two half hitches are placed over the back so that the knots lie against the animal’s spine when tightened. The first half hitch is behind the shoulder, and the second is in the flank, cranial to the udder or caudal to the penis. With the head secured, the rope is pulled with steady pressure until the animal lies down. The rope is tied with a quick-release knot cranial to the second half hitch to maintain rope pressure and keep the animal recumbent. The front and hind legs are bound together with hobbles or ropes. The legs are extended and tied to sturdy supports to secure the animal. Alternatively, for a quick procedure, the hind legs can be tucked under the second half hitch. The animal can be balanced against a wall, between bales of straw, or supported manually if dorsal recumbency is required.

FOOT RESTRAINT

Hind Feet

Hind feet commonly are raised to treat claws, manage leg wounds, or increase exposure to the udder and teats. The method described here is versatile and practical (Figure 4.3-5). One end of a rope is secured around the hind leg, dorsal to the hock, with a noose or quick-release honda. The free end of the rope is passed through a beam hook that is suspended from the ceiling. Coming from behind the cow, the rope is passed between the udder and hock, around the lateral aspect of the hock, and back through the beam hook. Pulling down on the free end of the rope, the pulley system created will elevate the hind leg as it bends at the stifle and hock. The free end of the rope is fastened by tying a quick-release knot around the rope itself close to the beam hook or by tying to the stanchion or another fixed object.

Front Feet

A third option uses one rope tied above the fetlock, run over the back of the animal, and secured (Figure 4.3-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree