Gerald van den Top

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Penis and Prepuce

Penile and preputial tumors are among the most common neoplasms of the horse. The prepuce and penis are covered with skin and thus can be affected by tumors of epithelial or mesenchymal origin. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in this region frequently causes discomfort but also can lead to more severe sequelae and even death.

Epidemiology and Etiologic Factors

In horses, 6% to 10% of all neoplasms affect the external genitalia, of which SCC is the most common, with an incidence of 49% to 82.5%. Penile and preputial SCC mainly affects adult horses at an average age of 17.4 to 19.5 years. Reports of possible breed predisposition for genital tumors are equivocal and difficult to interpret because of strong breed biases in many of the study populations. Certain breeds may have been overrepresented because of their relative abundance in the equine population in the study area. Ponies seem to be overrepresented among sufferers of male genital tumors, but this finding may be related to their longer life expectancy. Breeds with nonpigmented genitalia, such as Appaloosas and American Paint Horses, are thought to have a predilection for the development of SCCs.

In men, infection with papillomaviruses has been reported to be a risk factor for the development of SCC, but secondary factors must also be present. A similar etiology may be involved in horses because histopathologic investigations of equine penile tumors regularly report papillomas undergoing transition to SCCs. In horses, infection of the basal cell layer of the cutaneous epithelium with a host-specific papillomavirus is thought to be responsible for, and contribute to, the development of papillomas, and it has been suggested that papillomas of the penis and prepuce are caused by equine papillomavirus. In several studies, Equus caballus papillomavirus 2 (EcPV-2) was detected in equine penile papillomas, penile intraepithelial neoplasia, and equine SCCs. EcPV-2 is thought to be the main cause for penile and preputial SCC development in the horse.

Smegma also has repeatedly been proposed as an important etiologic factor in the formation of genital SCC on the basis of a study in which equine smegma induced growth of a papilloma and SCC at the site of injection in mice. However, assertions that smegma is carcinogenic, per se, cannot be justified from that study. In the horse, presence of a combination of penile SCCs and papillomas has been described, and it has been suggested that, although the papillomavirus may be the initiator of SCC development, smegma may act as a promoter. Poor hygiene, followed by chronic irritation and balanoposthitis, also has been proposed to induce formation of genital carcinomas in horses.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

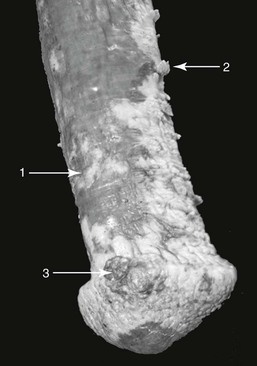

The clinical signs of preputial or penile SCC can result from the primary tumor or from secondary inflammatory processes. Signs commonly include depigmented plaques, irregularities of the penile or preputial surface, and nonhealing erosions with or without accompanying granulation tissue (Figure 98-1). In more advanced stages, the tumor can become a solid mass with or without a cauliflower-like appearance and may contain large necrotic areas. Clinical signs of SCC include sanguineous or purulent discharge, pungent odor secondary to infection that may be secondary to necrosis, edema of the prepuce, and disturbed micturition. Large SCCs can interfere with coitus or normal protrusion and retraction of the penis. Other signs may include excoriation of the penile or preputial integument, frequent protrusion of the penis, gait abnormality, and a wide-based stance. The glans penis is involved in 53% to 84% of cases of equine penile and preputial SCC.

Examination of a horse’s external genitalia for evidence of neoplasms should begin with visual inspection and palpation of the skin of the prepuce and scrotum. Assessment of an apparent primary tumor should include recording its size, mobility, invasiveness, and location (i.e., whether it involves the urethra, corpus cavernosum penis, corpus spongiosum penis, or a combination). Examination of the penis itself and internal fold of the prepuce may be difficult in the nonsedated horse because the horse tends to keep these structures retracted within the preputial cavity. Partial penile protrusion usually occurs during urination and can be provoked by placing the horse in a bedded stall or by administering a diuretic. Adequate inspection and palpation of the penis can be accomplished after injection of acepromazine (0.04 to 0.1 mg/kg, IV), detomidine (0.01 mg/kg, IV), or xylazine (0.5 to 1 mg/kg, IV). For horses that resist penile protrusion and examination, administration of a combination of 0.02 to 0.05 mg/kg acepromazine and 0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg xylazine has been reported to be effective, with penile relaxation being more profound and longer lasting than from administration of xylazine alone. Acepromazine induces more profound relaxation of the retractor penis muscle, and although detomidine may be slightly less effective than acepromazine in promoting penile protrusion, it induces placidity of the horse more quickly. It should be emphasized that phenothiazine tranquilizers have been reported to cause paraphimosis, priapism, and penile paralysis. None of these adverse effects have been associated with use of detomidine.

Ultrasonographic examination of the penis and prepuce may be useful for grossly determining the extent of the tumor and the degree of involvement of various structures. Ultrasonographic examination is easily performed, and the soft tissue structures are well suited for evaluation by this diagnostic technique.

Preoperative histologic evaluation of the primary tumor is required to classify the tumor and design a treatment plan. A tissue sample can be obtained by fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or by punch or excisional biopsy. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy can be used to identify cells with malignant features, but it is not a very reliable means of assessing SCCs because early neoplastic, hyperplastic, or dysplastic keratinocytes can appear similar cytologically. Because tumor architecture and depth of invasion can only be assessed with a larger sample, full-thickness biopsy of the lesion is more reliable diagnostically than FNAB. Independent of the type of tumor, the lesion can be so severe that complete excision is necessary in any case. In such cases, surgical removal or debulking can be combined with harvesting material for histologic examination.

Metastasis is a major concern in evaluation of horses with SCCs of the external genitalia. Tumor metastasis to the inguinal lymph nodes has been reported in 12.5% to 16.9% of male horses with genital SCC. Regional lymph nodes should therefore be palpated, but false-positive results can occur because penile neoplasms can become secondarily infected and lead to lymphadenopathy. Inguinal lymph node enlargement is detected in a relatively high proportion (34.1%) of horses with various penile and preputial tumor types, whereas metastases can be confirmed in only 32.1% of horses with enlarged inguinal lymph nodes. Palpation of the inguinal lymph nodes can be difficult in horses because of the extensive fat deposition in the inguinal region.

When a penile tumor metastasizes, the first lymph nodes affected are usually the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, followed by the medial iliac lymph nodes, which can be evaluated per rectum by palpation and by ultrasound. If enlarged lymph nodes are detected, samples collected by ultrasound-guided FNAB should be examined cytologically. Although identification of neoplastic cells is a reliable indicator of metastasis, failure to identify metastatic cells is less conclusive, and the absence of lymph node enlargement does not rule out metastasis. In 36% of cases in which lymph node enlargement could not be discerned, so-called occult metastasis was found after en bloc penile and preputial resection with penile retroversion or at postmortem histologic examination of the lymph nodes. Distant metastases, although rare, can sometimes be detected on lung radiographs.

Histologic Features

Histologically, invasive SCCs consist of small aggregates, irregular islands, nests, or cords of neoplastic keratinocytes that proliferate downward from the surface (epidermis) and invade the subepithelial stroma of the dermis. Frequent findings include keratin formation, horn pearls, mitoses, and cellular atypia. A high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, thick nuclear membranes, and clumped chromatin are often found. Depending on the differentiation grade, the overall architecture of the tissue can be still visible in well-differentiated tumors, whereas it is often absent in poorly differentiated SCCs. The term penile intraepithelial neoplasia, synonymous with carcinoma in situ, is used to describe a cluster of malignant cells that has not yet invaded the deeper subepithelial tissues and is limited in its extent to the epithelium.

Tumor Classification

Ideally, grading and staging of a tumor should permit accurate prediction of tumor behavior.

Grading

Histopathologic tumor grading involves assessment of anaplasia in cells obtained by biopsy or excision. The basis of grading is classification of the extent to which cancer cells are similar in appearance and function to healthy cells of the same tissue type. In brief, a well-differentiated or grade 1 SCC has minimal basal or parabasal atypia, whereas poorly differentiated or grade 3 tumors have minimal or no architectural and cellular similarity with normal tissue. Grade 2 includes all tumors not fitting into criteria described for grade 1 or grade 3. Squamous cell carcinoma can be heterogeneous, with areas of various degrees of differentiation observed in a single tumor.

Staging

A TNM staging system for penile and preputial SCCs, analogous to the system used for humans, has been described in horses (Table 98-1). In this system, the T describes the size of the tumor and whether it has invaded adjoining tissue, the N describes the extent of regional lymph node involvement, and the M refers to distant metastases. Staging is based on information about tumor spread obtained by physical examination and various imaging techniques (e.g., radiography, ultrasonography, and urethral endoscopy). Pathologic information is obtained through macroscopic and microscopic examination of the tumor margins and lymph nodes.

TABLE 98-1

TNM Classification in Penile and Preputial Tumors in the Horse

| TNM classification | ||||

| T | Primary tumor (physical examination, imaging, biopsy) | |||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (penile intraepithelial neoplasia) | |||

| Ta | Noninvasive verrucous carcinoma | |||

| T1 | T1a: Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue of the penis or prepuce without lymphovascular invasion | |||

| T1b: Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue of the penis or prepuce with lymphovascular invasion | ||||

| T1c: Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue of the penis and prepuce with or without lymphovascular invasion | ||||

| T2 | Tumor invades corpus spongiosum or corpus cavernosum penis | |||

| T3 | Tumor invades urethra | |||

| T4 | Tumor invades other adjacent structures | |||

| N | Regional lymph nodes (physical examination, imaging, biopsy) | |||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |||

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |||

| N1 | Metastasis is bilateral or unilateral in inguinal lymph nodes | |||

| N2 | Metastasis in inguinal lymph node or nodes fixed to surrounding tissue | |||

| N3 | Metastasis in pelvic lymph node or nodes | |||

| M | Distant metastasis (physical examination and imaging) | |||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | |||

| pTNM pathologic classification | ||||

| The p categories correspond to the T and N categories of histologically assessed penile and preputial tumors. The pN categories are based on surgical excision followed by histologic assessment. pM1 refers to distant metastasis that has been microscopically confirmed. | ||||

| Stage grouping | ||||

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | |

| Ta | N0 | M0 | ||

| Stage I | T1a | N0 | M0 | |

| T1b | N0 | M0 | ||

| Stage II | T1c | N0 | M0 | |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | ||

| T3 | N0 | M0 | ||

| Stage IIIA | T1, T2, T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| Stage IIIB | T1, T2, T3 | N2 | M0 | |

| Stage IV | T4 | Any N | M0 | |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | ||

| Any T | Any N | M1 | ||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree