CHAPTER 3 Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues

NORMAL HISTOLOGY AND CYTOLOGY

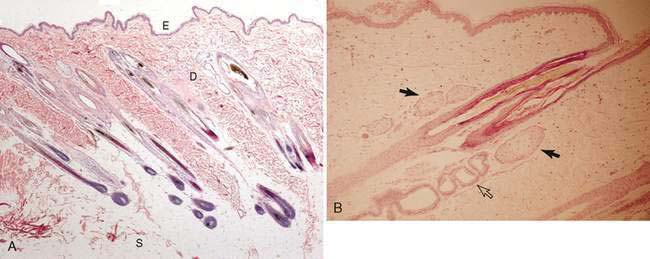

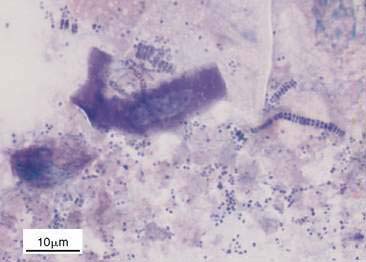

There are regional differences in histology of the skin of the dog and cat related to the thickness of the epidermis and dermis (Fig. 3-1A). In general, the epidermis is composed of several layers of squamous epithelium, including a keratinized layer, a granular layer, a spinous layer, and a basal layer. The adnexal structures of the epidermis include hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands (Fig. 3-1B). The dermis present below the epidermal layer contains the adnexal structures, smooth muscle bands, blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves, and variably sized collagen and elastic fibers. Beneath the dermis lies the subcutis, composed of loose adipose tissue and collagen bundles. Normal cytology of the dermis and subcutis contains a mixture of epidermal squamous epithelium and well-differentiated glandular elements as well as mature adipose and collagen tissue. Basal epithelial cells are round and deeply basophilic with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. Cells of the other epidermal layers are known as keratinocytes because of their composition of keratin. Polygonal cells of the granular layer are evident cytologically by the presence of basophilic to magenta keratohyalin granules within an abundant lightly basophilic cytoplasm having a small, contracted nucleus. The most superficial keratinized layer consists of flattened, sharply demarcated, blue-green hyalinized squames that lack a nucleus. Elongated dark-blue to purple squames are termed keratin bars, which represent rolled or coiled cells. Melanocytes from neural crest origin are located within the basal layer of the epidermis or hair matrix. Their brownish-black to greenish-black fine granules may be seen in some keratinocytes. Also present may be a low number of mast cells from perivascular and perifollicular sites.

NORMAL-APPEARING EPITHELIUM

Presence of only mature epithelium in a skin mass most often indicates a non-neoplastic condition.

Non-neoplastic noninflammatory tumor-like lesions account for approximately 10% of skin lesions removed from dogs and cats (Goldschmidt and Shofer, 1992). These include cysts and glandular hyperplasia.

Epidermal Cyst or Follicular Cyst

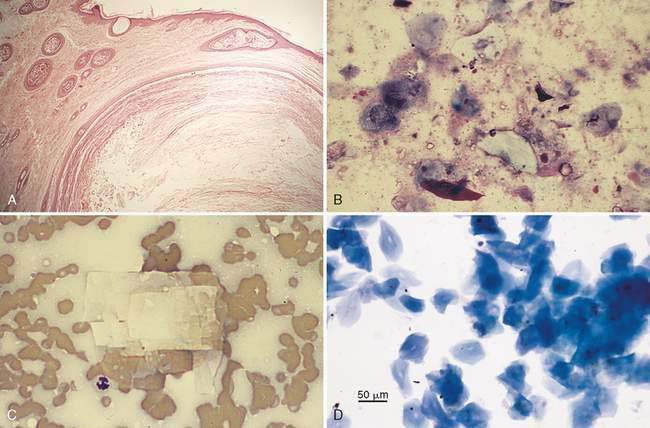

Also termed epidermal inclusion cysts or epidermoid cysts, these cysts are found in one third to one half of the non-neoplastic noninflammatory tumor-like lesions removed in dogs and cats, respectively (Goldschmidt and Shofer, 1992). They occur most frequently in middle-aged to older dogs (Yager and Wilcock, 1994). Cysts may be single or multiple, firm to fluctuant, with a smooth, round, well-circumscribed appearance. These are often located on the dorsum and extremities (Goldschmidt and Shofer, 1992). The cyst lining arises from well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 3-2A). By definition, the lack of adnexal differentiation without a connection to the skin surface seen histologically is termed an epidermal inclusion cyst. The more common follicular cyst is characterized by a distended hair follicle infundibulum that opens to the surface via a pore (see Fig. 3-2A). The distinction cannot be made cytologically. Keratin bars, squames, or other keratinocytes predominate on cytology (Fig. 3-2B). Degradation of cells within the cyst may lead to the formation of cholesterol crystals, which appear as negative-stained, irregularly notched, rectangular plates best seen against the amorphous basophilic cellular debris of the background (Fig. 3-2C). They are thought to arise from frictional trauma leading to obstruction of follicular ostia when found on pressure points. Nailbed cysts (Fig. 3-2D) are thought to occur from trauma that allows embedment of germ layer epidermis in underlying tissue creating an epithelial inclusion cyst (Gross et al., 2005). Multiple cysts may have a developmental and/or environmental basis for their formation (Gross et al., 2005). The behavior of these masses is benign, but rupture of the cyst wall can induce a localized pyogranulomatous cellulitis. When this occurs, neutrophils and macrophages may be frequent. To prevent this inflammatory response, surgery is frequently suggested and the prognosis is excellent.

Nodular Sebaceous Hyperplasia

Grossly, these masses are single to multiple and often resemble a wart. Most are less than 1 cm in diameter. They are firm, elevated, with a hairless, cauliflower or papilliferous surface. Sebaceous hyperplasia is more prevalent than sebaceous adenoma (Yager and Wilcock, 1994). They are very common in old dogs and less common in cats. Distinction cannot be made cytologically and may even be difficult histologically when distinguishing between sebaceous hyperplasia and sebaceous adenoma. Symmetrical proliferation of mature sebaceous lobules grouped around a keratinizing squamous-lined duct is the histopathologic basis used to classify the condition as hyperplasia (Gross et al., 2005). Mature sebaceous epithelial cells are seen cytologically, sometimes in clusters, or as individual pale, foamy cells with a small, dense, centrally placed nucleus, often mistaken for phagocytic macrophages. These are benign proliferations that have an excellent prognosis following surgical excision.

NONINFECTIOUS INFLAMMATION

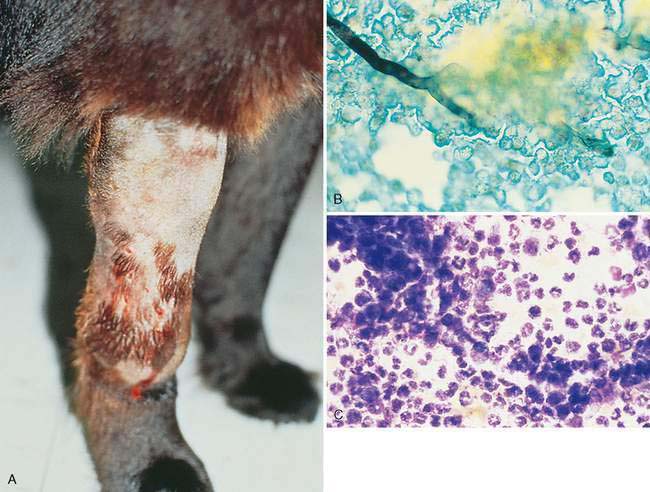

Acral Lick Dermatitis/Lick Granuloma

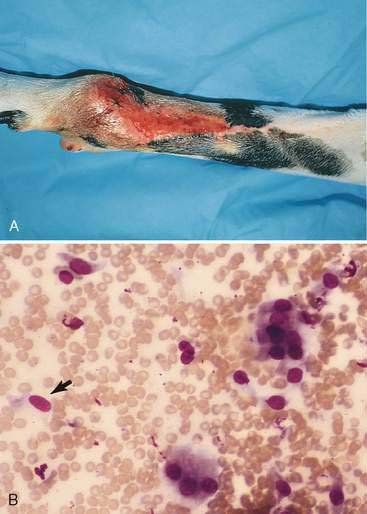

This is a chronic inflammatory response to persistent licking or chewing of a limb, producing a thickened, firm, raised plaque lesion that often becomes ulcerated (Fig. 3-3A). Causes include infectious agents, hypersensitivity reactions, trauma, and psychogenesis. Cytologically, there is a mixed population of mononuclear inflammatory cells, including plasma cells, along with intermediate squamous epithelium (Fig. 3-3B) related to acanthosis, i.e., hyperplasia of the epidermal stratum spinosum layer. The healing response to surface erosion may produce fibroblastic cells, which appear in the cytologic specimens as plump, fusiform cells along with numerous erythrocytes related to increased vascularization. Lesions may also involve a secondary bacterial infection with suppuration. Treatment will be determined by the underlying cause, and frequently involves control of the superficial pyoderma.

Foreign Body Reaction

These reactions are caused by penetration of plant, animal, or inorganic material into the skin, producing an erythematous wound that progresses to a nodular response that often drains fluid. Cytologically, a mixed inflammatory response is present, composed mostly of macrophages and lymphocytes with smaller numbers of neutrophils and possibly eosinophils (Fig. 3-4A-C). Multinucleated giant cells are frequently present. A fibroblastic response is common. A secondary bacterial infection may occur. Treatment includes surgical exploration or excision with histologic biopsy and culture if warranted.

Arthropod Bite Reaction

Bites from insects, ticks, and spiders, for example, may induce a mild to severe reaction characterized usually by erythema and swelling with acute necrosis that appears as eosinophilic furunculosis or later as a granuloma on histopathology (Gross et al., 2005). Cytology reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils, macrophages, and usually increased numbers of eosinophils related to a hypersensitivity reaction (Fig. 3-5A-B). These lesions often regress spontaneously, but some may require additional wound care.

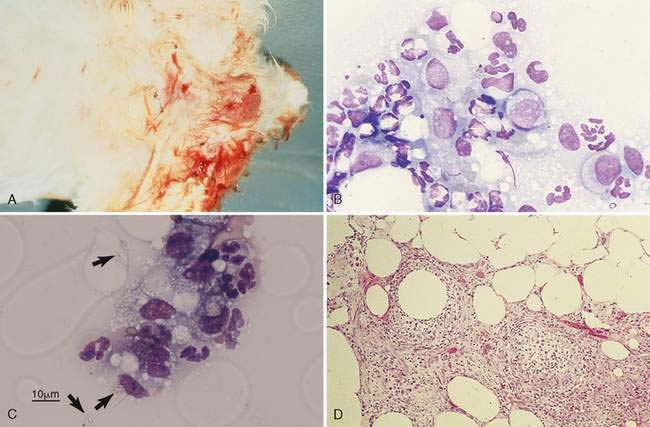

Nodular Panniculitis/Steatitis

Causes of noninfectious panniculitis include trauma, foreign bodies, vaccination reactions, immune-mediated conditions, drug reactions, pancreatic conditions, nutritional deficiencies, and idiopathy. The condition appears in the cat and dog as solitary or multiple, firm to fluctuant, raised, well-demarcated lesions. These may ooze an oily yellow-brown fluid (Fig. 3-6A). Sites of prevalence include the dorsal trunk, neck, and proximal limbs. Cytologically, nondegenerate neutrophils and macrophages predominate against a vacuolated background composed of adipose tissue (Fig. 3-6B&C). Small lymphocytes and plasma cells may be numerous, especially in lesions induced by vaccination reactions. Frequently macrophages present with abundant foamy cytoplasm or as giant multinucleated forms. When chronic, evidence of fibrosis is indicated by the presence of plump fusiform cells with nuclear immaturity. The fibrosis may be so extensive as to suggest a mesenchymal neoplasm. Prognosis is usually best for solitary lesions, which respond to surgical excision. Histologically, sterile panniculitis may demonstrate inflammatory cells within the subcutis (Fig. 3-6D) that extend into the dermis. Multiple lesions are often associated with systemic disease in young dogs, and treatment involves glucocorticoid administration. Dachshunds and poodles may be predisposed to this form of the disease. Culture and histopathologic examination are recommended to rule out infectious causes. Fungal stains should be applied to cytologic specimens.

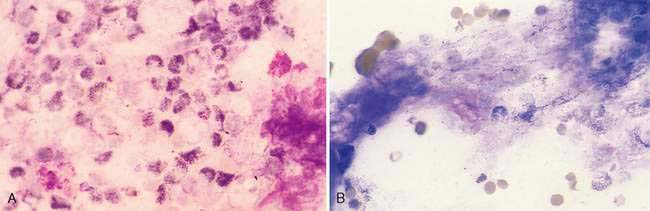

Eosinophilic Plaque/Granuloma

Eosinophilic granuloma occurs in dogs and young cats in response to a hypersensitivity reaction, similar to plaque formation. Grossly, lesions may appear as raised linear bands of yellow to erythematous tissue along the posterior legs or as papules and nodules on the nose, ears, and feet. Lesions have been seen in the oral cavity. Cytologically, a mixed inflammatory response is seen, with macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and increased numbers of eosinophils and mast cells (Fig. 3-7A). Rarely multinucleated giant cells may be present. Collagen necrosis may occur as a result of eosinophil granule release giving rise to the occasional appearance of amorphous basophilic material in the background (Fig. 3-7B). Eosinophil numbers are usually less than are seen in eosinophilic plaque. Surgical excision is recommended for solitary nodular lesions.

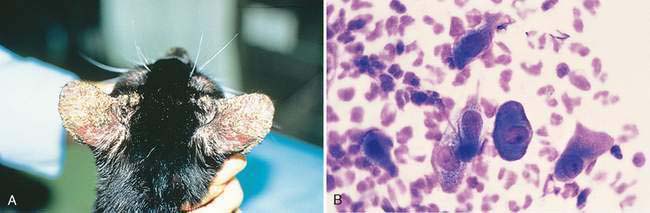

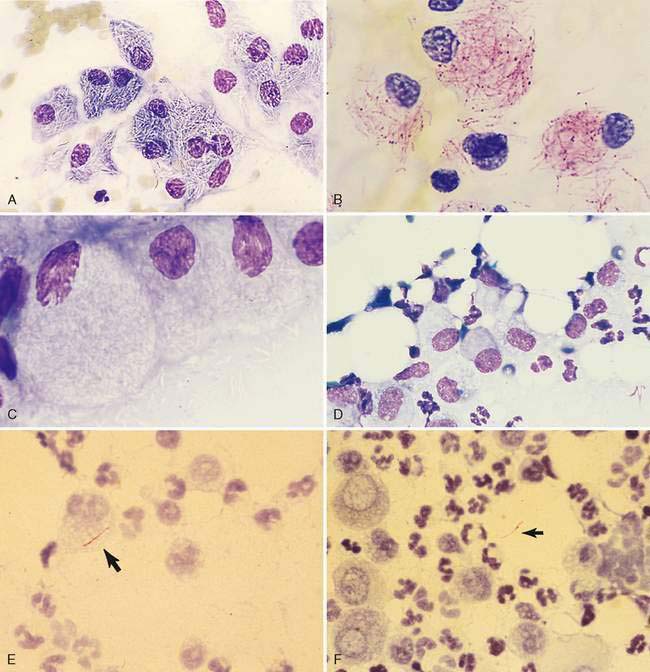

Pemphigus Foliaceus

This is the most common autoimmune skin disease in dogs and cats. Drugs, chronic disease, and spontaneous causes have been associated with their occurrence. Grossly, lesions appear as erythematous macules that progress to white or yellow pustules and finally to crusts (Fig. 3-8A). The head and feet are preferred sites although the ears, trunk, and neck are also commonly affected in the cat. Direct imprint of the underside of a crust or aspiration of a pustule reveals nondegenerate neutrophils and acantholytic cells appearing as intensely stained individualized oval keratinocytes (Fig. 3-8B). Eosinophils may be present as well, but bacterial infection is usually lacking. Treatment includes antibiotics and immunotherapy. Excisional biopsy of early lesions is recommended. Histologic examination along with direct immunofluorescent antibody tests or direct immunoperoxidase staining tests is necessary to distinguish the different pemphigus subtypes. Antinuclear antibody tests also may be helpful.

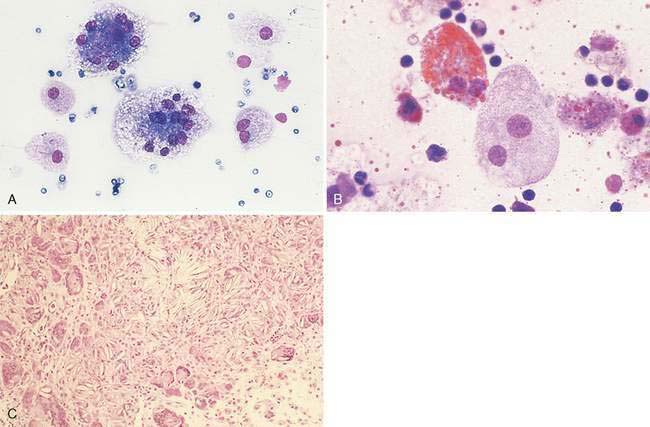

Cutaneous Xanthoma

Xanthomatosis is an uncommon granulomatous inflammation in cats, birds, and amphibians related to primary or secondary diabetes mellitus, high-fat diets, and hereditary hyperchylomicronemia (Gross et al., 2005). The deposition of cholesterol and triglycerides in tissues results in lipid-laden macrophages. Grossly, the lesions are single or multiple, white to yellow plaques or nodules that may ulcerate or drain caseous material. Sites preferred are the face, trunk, and foot pads. Cytologically, aspirates contain numerous foamy macrophages (Fig. 3-9A) that stain positive with lipid stains (Fig. 3-9B). Lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils or neutrophils are present as well. Histologically, cholesterol clefts and giant cells may be prominent (Fig. 3-9C). Treatment is aimed at identifying and controlling the underlying cause.

INFECTIOUS INFLAMMATION

Acute Bacterial Abscess and Pyoderma

The abscess is a common subcutaneous lesion in cats and dogs, often related to bites or other penetrating wounds. This may be localized to the skin or associated with systemic signs. The area is firm to fluctuant, swollen, erythematous, warm, and painful. A creamy white exudate may be aspirated that is characterized cytologically by numerous degenerate neutrophils displaying karyolysis, karyorrhexis, and pyknosis (see Chapter 2). Bacteria may be found in association with the swollen, round nuclei. Case management includes culture and sensitivity tests, with treatment aimed at surgical incision and antibiotics.

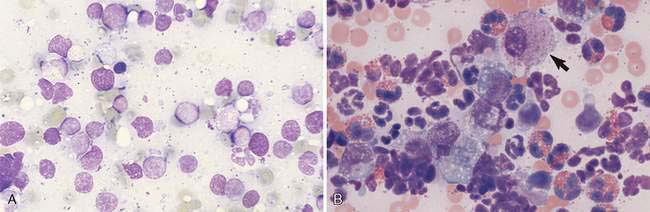

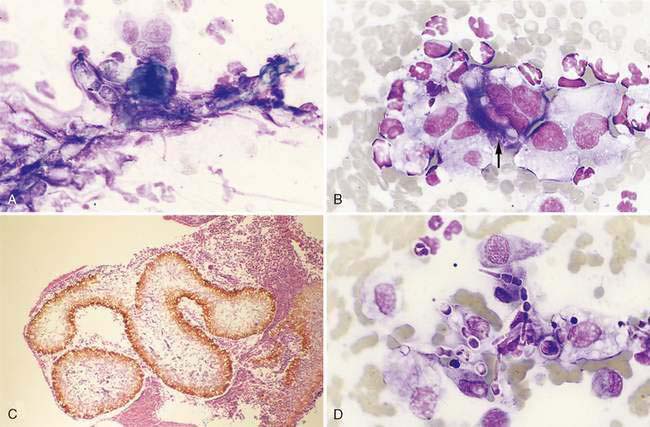

Deep pyoderma is manifest as a bacterial inflammation that extends into the dermis and hair follicles with subsequent damage to the follicle (furunculosis). The ruptured follicular wall releases fragments of the hair shaft as well as follicular keratins into the surrounding tissue that creates a foreign body reaction and pyogranulomatous inflammation with formation of a dermal nodule (Gross et al., 2005; Raskin, 2006a). Staphylococcus intermedius is typically the primary pathogen but other bacteria and underlying conditions may be occurring to initiate the inflammation. Ulceration is common. Mixed inflammatory cells including neutrophils and macrophages are present (Fig. 3-10A&B).

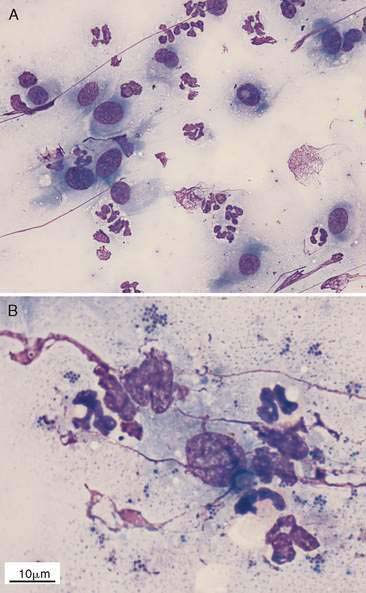

Clostridial Cellulitis

The infection is usually associated with penetrating wounds. The swollen skin may be crepitant with a serosanguineous wound exudate. Cytologically, tissue aspirates may reveal large rods measuring 1 × 4 μm, some with a clear, oval, subterminal endospore, occurring singly or in short chains (Fig. 3-11A). This anaerobic organism is gram positive (Fig. 3-11B), but may stain variably as a result of a chronic infection or antibiotic therapy. The specimen background often contains cellular debris and lipid with few, if any, inflammatory cells. Neutrophils, when present, are often degenerate. Anaerobic culture is necessary for diagnosis. Treatment includes surgical management and appropriate antibiotic administration.

Rhodococcus equi Cellulitis

The presence of numerous neutrophils and macrophages with the latter containing small rod to coccoid bacteria should suggest infection from Rhodococcus sp. Case reports describe ulcerative swellings that often occur on extremities and involve adjacent lymph nodes (Patel, 2002). These are opportunistic bacteria for which immunosuppressed animals are at higher risk.

Actinomycosis/Nocardiosis

The infection presents as subcutaneous swellings that progress to ulceration with exudation of red-brown fluid. The cause is often related to penetrating wounds. The infections may be associated with systemic signs that often include pyothorax. Cytologically, degenerate neutrophils predominate, with macrophages and small lymphocytes also present. Bacteria may be intracellular or extracellular, the latter often found as dense clusters of organisms (Fig. 3-12A-C). These bacteria are slender, filamentous, branching, lightly basophilic rods with red spotted or beaded areas. They may be highlighted with a silver stain (Fig. 3-12D). Histologically, inflammatory cells group around dense mats of organisms (Fig. 3-12E). Actinomyces sp. are gram positive and acid-fast negative, whereas Nocardia sp. are gram positive but variably positive for acid-fast stain. Culture is necessary for diagnosis of the specific type and samples should be obtained anaerobically. Treatment includes surgical drainage and appropriate antibiotics.

Dermatophilosis

This is a rare infection that has been reported in cats and dogs, usually as the result of penetrating wounds contaminated with infected soil or water. The lesion presents as a firm, alopecic, subcutaneous draining mass. The thick gray exudate below the crusted surface is purulent, with numerous degenerate neutrophils but few eosinophils and macrophages. The organism appears as gram-positive branching filaments that segment horizontally and longitudinally into coccoid forms (Fig. 3-13). Diagnosis is made by morphologic identification of the organism on biopsy or through culture. Treatment involves appropriate antibiotics and appropriate wound management (Carakostas et al., 1984; Kaya et al., 2000).

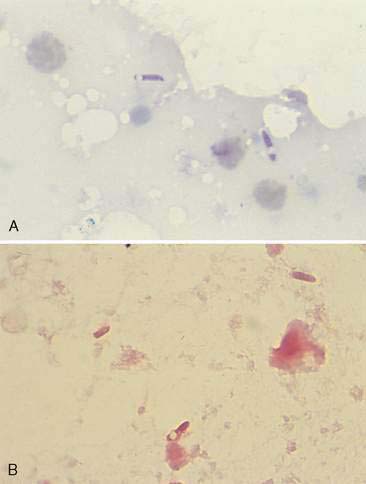

Mycobacteriosis

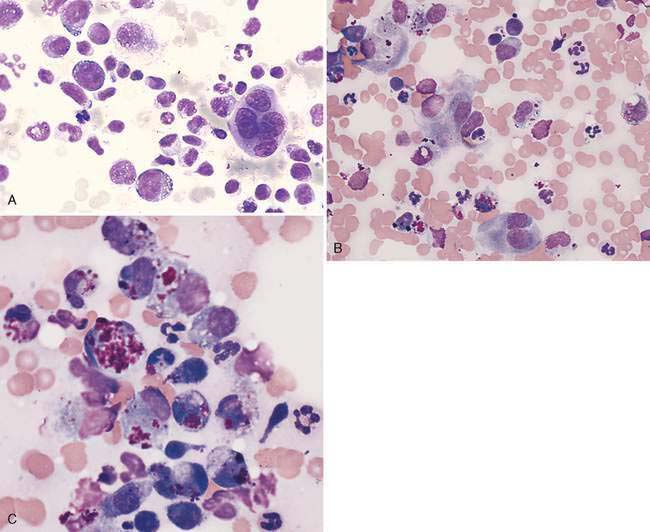

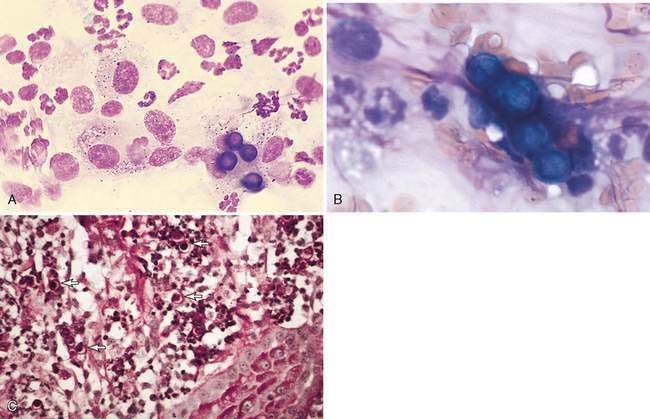

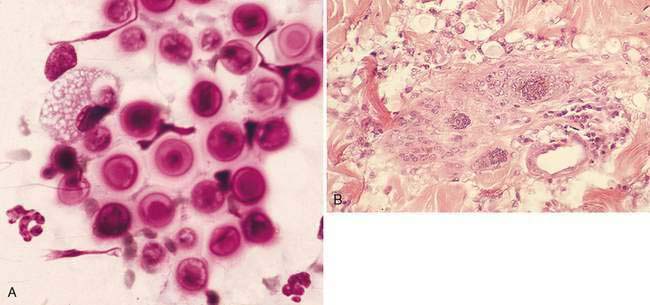

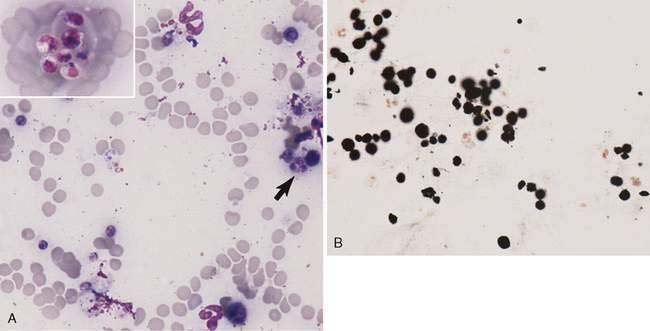

Three clinical forms of mycobacteriosis in dogs and cats are recognized, which include internal tuberculous, localized cutaneous nodules (lepromatous), and spreading subcutaneous forms (Greene and Gunn-Moore, 2006). Diagnosis is best performed by tissue culture and histopathology. Definitive identification may be made by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of tissue specimens. Treatment may include surgical excision and appropriate antibiotics. The tuberculous form is related to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, or the opportunistic Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. Contact with infected people, cattle, birds, or soil may be documented. The disease may be also associated with immunosuppressed animals. This form is characterized by a systemic disease with weight loss, fever, and lymphadenopathy. While internal organs are most affected, skin nodules can appear on the head, neck, and legs of dogs and cats (Miller et al., 1995). These are slow-growing organisms normally requiring 4 to 6 weeks to culture. Detection may be hastened to 2 weeks and may require PCR and other molecular techniques for identification. Cytologically, macrophages contain few to many beaded bacilli, and some organisms may be extracellular (Fig. 3-14A). Acid-fast staining is helpful in the recognition of the organisms (Fig. 3-14B). Lymphocytes and neutrophils are more abundant than in lepromatous forms.

The lepromatous form in cats is caused by Mycobacterium lepraemurium and is common in wet, cooler climates with exposure to infected rodents. A novel, unnamed Mycobacterium species has been documented for dogs in Australia, New Zealand, and recently in the United States (Foley et al., 2002). Nonpainful raised nodules are found on the head and distal limbs without systemic signs in cats. These nodules are soft to firm, fleshy, and often localized, with occasional ulceration and little exudation. Spontaneous remission has been reported in a cat (Roccabianca et al., 1996). Nodules in dogs are smooth to ulcerated, occurring frequently on the head, particularly the ears and muzzle. Cultivation of the organism is difficult. Cytologically, macrophages containing numerous intracellular organisms predominate (Twomey et al., 2005) (Fig. 3-14C). Other cells seen include lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and occasional multinucleated giant cells.

The more common presentation of cutaneous mycobacteriosis in dogs and cats involves those fast-growing species having an atypical growth pattern or culture characteristic, such as Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonei, and Mycobacterium smegmatis. These are the result of inoculation with contaminated soil or standing water. Lesions are characterized by a spreading subcutaneous pyogranulomatous inflammation having frequent draining tracts. This form also lacks systemic signs. Bacterial culture of deep tissue sites is required and growth may occur within 3 to 5 days. Cytologically, a mixed population of neutrophils and macrophages predominates, with occasional lymphocytes, plasma cells, multinucleated giant cells, or reactive fibroblasts (Fig. 3-14D). Organisms are occasionally found on cytology with the aid of acid-fast staining (Fig. 3-14E&F). On histopathology, lesions appear diffuse and organisms may be found within lipocysts surrounded by inflammatory cells. Prognosis for this form is guarded, as response to antibiotics is often unrewarding.

Localized Opportunistic Fungal Infections

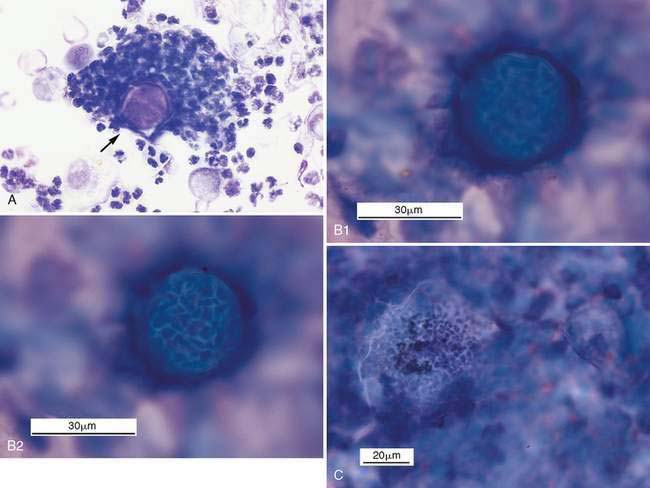

Cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions occur as the result of penetrating wounds contaminated with infected soil or water, commonly in tropical or subtropical climates. One common type is phaeohyphomycosis, caused by a group of dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi such as Alternaria, Curvularia, or Bipolaris spp. (Fig. 3-15A-C). A rare type is hyalohypomycosis, produced by nonpigmented fungi such as Paecilomyces spp. (Fig. 3-15D) (Elliott et al., 1984). Nodules develop slowly, usually on extremities, later becoming ulcerated with draining tracts. Cytologically, these produce a pyogranulomatous inflammation with degenerate neutrophils, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and mature fibroblasts. Hyphal structures are septate and periodic constrictions may be seen producing globose dilations. Yeast forms rarely occur. Diagnosis involves histopathologic biopsy and tissue culture. Treatment involves surgical excision but prognosis is often poor to guarded.

Cutaneous Lesions from Systemic Fungal Infections

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is a pyogranulomatous or granulomatous inflammation of dogs and, rarely, cats that is related to yeast and rare hyphal forms of Blastomyces dermatitidis. The disease is endemic in areas around the Mississippi and Ohio River basins and into Canada. Lesions appear often on the extremities and nose. Cytologically, degenerate neutrophils, macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes are present. Yeast forms measure 7 to 15 μm in diameter and have a refractile, deeply basophilic, thick cell wall (Fig. 3-16A&B). Organisms may be phagocytized by macrophages or found extracellularly. Cell division occurs by budding that is broad based compared with the narrow-based budding of Cryptococcus sp. Structures stain positive with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) (Fig. 3-16C) and methenamine silver. Definitive diagnosis involves immunostaining of tissue sections and tissue culture. Serum tests involve agar gel immunodiffusion and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods but they have low sensitivity. Confirmation of organisms found on biopsy may be performed by PCR assays.

Coccidioidomycosis

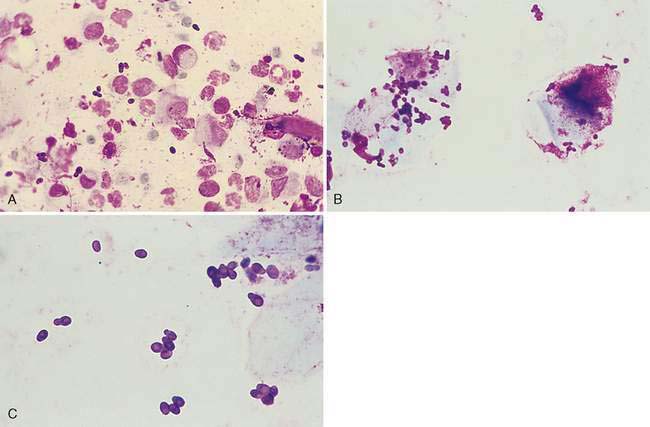

This disease, caused by Coccidioides immitis, produces a pyogranulomatous response similar to that of blastomycosis in dogs and occasionally cats. It is endemic in the southwestern United States. Cytologically, the organism appears as thick-walled spherules measuring 20 to 200 μm diameter (Fig. 3-17A). Within the basophilic spherule (Fig. 3-17B) are uninucleate round endospores measuring 2 to 5 μm in diameter. The free endospores (Fig. 3-17C) may be confused with yeast forms of Histoplasma. Empty small spherules resemble Blastomyces. Both cell wall and endospores stain positive with methenamine silver, while PAS stains the cell wall purple and the endospores red. Intact spherules are poorly chemotactic for neutrophils compared with free endospores, which attract many neutrophils (see Fig. 3-17A). Serologic tests used include tube precipitin (IgM), complement fixation (IgG), latex agglutination, agar gel immunodiffusion, and ELISA. Fluorescent antibody methods may be used for tissue biopsy. Tissue culture is not recommended because of the public health risk. When results are equivocal, commercial testing using a DNA probe with a chemiluminescent label may be used (Beaudin et al., 2005).

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis is found in several geographic areas, but frequently in tropical or subtropical climates or with soil infected by pigeon droppings. Lesions in dogs and cats may present as crusts or erosions on the nose in addition to nodules. The cellular response is often granulomatous with macrophages predominating (Fig. 3-18A&B). Other cells present include lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There is minimal inflammation in immunocompromised patients and when organisms retain their thick outer capsule. The causative agent, Cryptococcus neoformans, is found in cytologic specimens as a round to oval yeast form measuring 4 to 10 μm in diameter. Cell sizes may be variable, ranging from 2 to 20 μm. When present, the thick lipid capsule remains unstained with Romanowsky-type stains (see Figure 5-11B). As a result, the biopsy background appears vacuolated, often with many dense, round cell bodies. Stains such as new methylene blue and India ink are used to enhance visibility of the capsule on unstained specimens (see Figure 5-11C). The internal cell body stains positive with methenamine silver and PAS, while the cell wall requires mucicarmine stain. Cell division involves narrow-based budding compared with the broad-based budding of Blastomyces. Definitive diagnosis involves immunostaining in tissue biopsies, latex agglutination test, ELISA, or fungal culture. Confirmation in difficult cases may involve PCR and detection of the CAP59 gene.

Histoplasmosis

This disease produces a pyogranulomatous response by the agent Histoplasma capsulatum, and is similar in geographic distribution to blastomycosis. Bird and bat droppings provide an ideal growth medium for the organisms. Cutaneous lesions (Fig. 3-19) are uncommon compared with those in gastrointestinal and hematopoietic organs. Cytologically, macrophages predominate, but lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional multinucleated giant cells may be present. Numerous intracellular and extracellular oval yeast forms measuring 2 to 4 μm are frequently found in specimens. They stain positive with PAS and methenamine silver. The yeast structures resemble the protozoan Leishmania except Histoplasma has a clear halo due to cell shrinkage and the cell body lacks a kinetoplast. Definitive diagnosis of histoplasmosis requires identification by cytology, immunostaining in tissue biopsy, or fungal culture. There are no reliable serologic tests. Molecular tests have been used on a limited basis.

FIGURE 3-19 Histoplasmosis. Cat. Skin lesions as well as ocular lesions were present around the eyes in this cat.

(Courtesy of Heidi Ward, Gainesville, FL.)

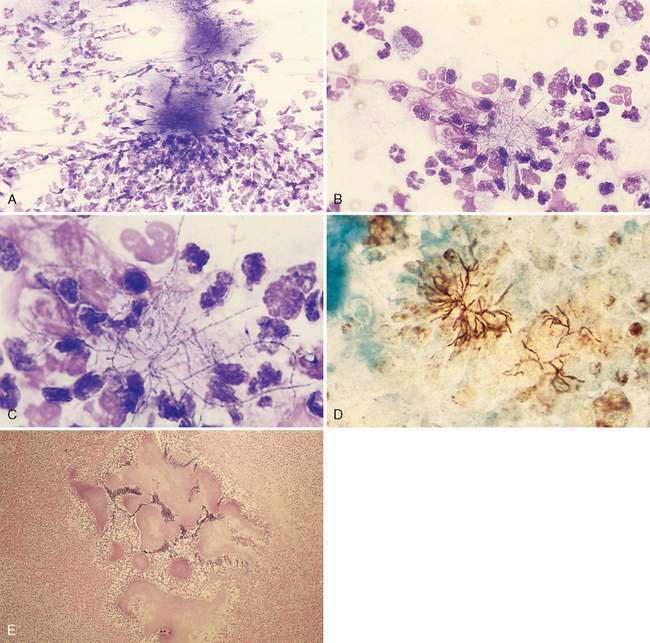

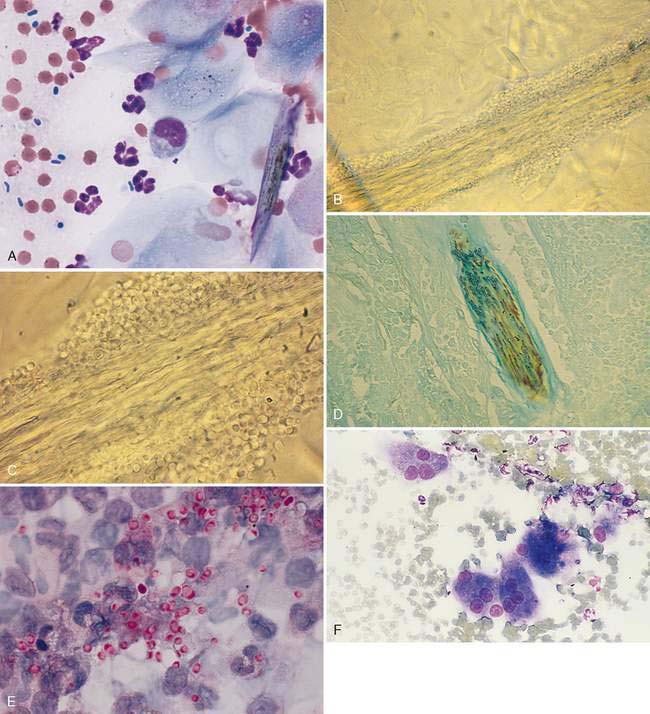

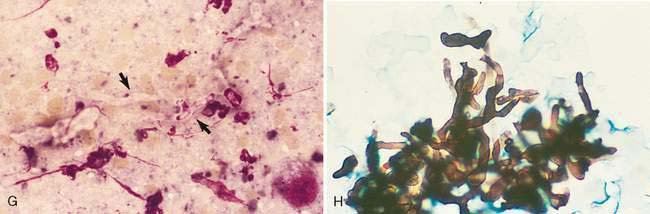

Dermatophytosis

This is a common infectious and often contagious disease to humans that frequently involves the superficial layers of the skin, hairs, and nails. Microsporum and Trichophyton sp. are the most common genera of dermatophytes associated with dogs and cats. The lesions typically present with focal alopecia, broken hair shafts, crusts, scales, and erythema on the head, feet, and tail of dogs and cats (Caruso et al., 2002). Less commonly seen are raised or dermal nodules called kerions (Logan et al., 2006). A kerion forms when the infected hair follicle ruptures and both the fungus and keratin spill into the dermis, eliciting an intense inflammatory response. Cytologic specimens reveal a pyogranulomatous inflammation with degenerate neutrophils and large epithelioid macrophages. Arthrospores that measure 2 to 4 μm possess a thin, clear capsule (Fig. 3-20A). The arthrospores and nonstaining hyphae are associated with hair shafts, which are best visualized using clearing agents with plucked hairs (Fig. 3-20B&C) or methenamine silver staining (Fig. 3-20D) or PAS (Fig. 3-20E). Fungal culture is necessary for identification.

An uncommon presentation is a dermatophytic pseudomycetoma, usually seen in Persian cats, that is most often caused by Microsporum canis (Zimmerman et al., 2003). It presents as a nodular granuloma with fistulous tracts deep into subcutaneous tissues. Cytologically, this involves macrophages with abundant foamy cytoplasm and numerous multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 3-20F). Arthrospores may be present along with fungal hyphae that have an irregular shape and size and may stain variably with Romanowsky-type stains (Fig. 3-20G). Positive staining occurs with PAS and methenamine silver (Fig. 3-20H). Treatment of the nodules involves surgical excision and antifungal drugs.

Malassezia

The causative agent, Malassezia pachydermatis, is an opportunistic invader of the skin and ear canal. It is associated with widespread seborrheic dermatitis as well as otitis externa in dogs. Organisms are found in surface scabs or crusts of exudative lesions. Sites of predilection include the face, ventral neck, dorsum of paws, ventral abdomen, and caudal thighs. Cytologically, the skin infection involves primarily a mononuclear inflammation, with lymphocytes and macrophages, but secondary pyoderma may occur with the presence of focal neutrophils (Fig. 3-21A). Typically, the ear infection is minimally inflamed with organisms adhered to squamous epithelium (Fig. 3-21B). Romanowsky stains reveal purple, broad-based budding organisms characterized by a bottle or shoe shape (Fig. 3-21C). Treatment includes surface cleaning and appropriate antifungal agents.

Oomycosis

Two agents, Pythium insidiosum and Lagenidium sp., are water molds of the oomycete class in the Stromenopila kingdom (Grooters et al., 2003). They differ from true fungi in producing motile, flagellate zoospores, having cell walls without chitin, and having differences in nuclear division and cytoplasmic organelles. This disease is common in dogs and occasional in cats from tropical or subtropical climates, such as the southeastern United States. Animals are infected by standing in or drinking contaminated water. Systemic signs result from gastrointestinal involvement, and are more common than the cutaneous presentation. Dermal ulcerative nodules develop into draining tracts and serosanguineous exudation from sites that include the extremities, tail head, and perineum (Fig. 3-22A). Cytologically, specimens consist of a pyogranulomatous inflammation with increased eosinophils and the presence of broad, poorly septate, and branching hyphal elements. While Pythium hyphae are uniform, Lagenidium hyphae tend to have larger diameters and more bulbous shapes than Pythium. Methenamine silver stain is preferred over PAS stain to demonstrate the organisms (Fig. 3-22B). Serum testing for antibodies to oomycete antigens is helpful as a screening test. Culture of infected tissues followed by both morphologic and molecular identification of the pathogen is highly recommended. Immunohistochemistry uses a polyclonal antibody specific for Pythium insidiosum, not Lagenidium. However, distinction between the two oomycetes is best performed by rRNA gene sequencing or specific PCR amplification. Possible treatment involves wide surgical excision or amputation of affected limbs. Prognosis is guarded to poor.

Organisms stain poorly with Romanowsky stains and are best seen within dense clumps of inflammatory cells at low magnification. The presence of clear, uniformly sized, linear strands suggest hyphal elements (Fig. 3-22C), but these must be distinguished from collagen debris, which may also appear as unstained strands.

Protothecosis

This is a rare disease in dogs and cats related to achloric algae, Prototheca wickerhamii, that is found in sewage-contaminated food and water. It is frequently associated with immunosuppression or concurrent disease. Cats usually develop a cutaneous disease, while dogs may develop both cutaneous and systemic forms. Systemic involvement primarily includes the gastrointestinal tract, eye, and nervous system. Cutaneous lesions in dogs are chronic, nodular, exudative, and ulcerative, occurring on the trunk and extremities. Large, firm nodules on limbs, feet, head, and tail base have been reported in cats. Cytologically, the inflammation is granulomatous or pyogranulomatous. Epithelioid macrophages predominate, but lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional multinucleated giant cells may also be found. Organisms, present outside or within macrophages, measure 5 to 20 μm in diameter (Fig. 3-23A). They are round to oval with internal septation producing 2 to 20 endospores within the cell wall. The endospores are basophilic and granular with a single nucleus, and have a clear halo around them. Both PAS and methenamine silver stains demonstrate the cell wall (Fig. 3-23B). Definitive diagnosis requires culture or tissue biopsy using immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase techniques. Treatment involves surgical excision for cutaneous lesions. Antimicrobial drugs have been used with limited success in systemic forms. Prognosis is guarded to poor.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree