CHAPTER 2 General Categories of Cytologic Interpretation

One use of cytology is to classify lesions so as to assist with the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of a case. Cytologic interpretations are generally classified into one of five cytodiagnostic groups (Box 2-1). A sixth category can be used for nondiagnostic interpretations. Nondiagnostic samples usually result from insufficient cellular material or excessive blood contamination.

NORMAL OR HYPERPLASTIC TISSUE

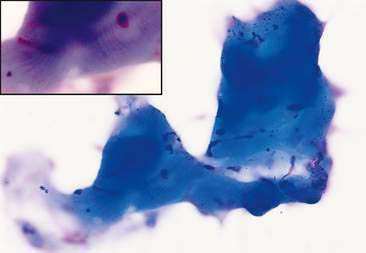

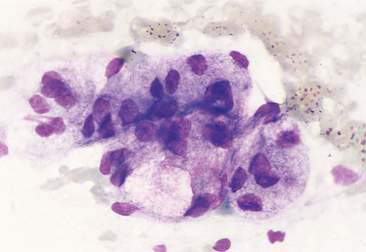

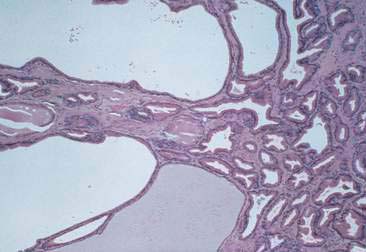

Normal and hyperplastic tissues are both composed primarily of mature cell types. Normal cells display uniformity in cellular, nuclear, and nucleolar size and shape. Cytoplasmic volume is usually high relative to the nucleus (Figs. 2-1 and 2-2). Hyperplasia is a nonneoplastic enlargement of tissue that can occur in response to hormonal disturbances or tissue injury. Hyperplastic tissue has a tendency to enlarge symmetrically in comparison to neoplasia. Cytologically, hyperplastic cells have a higher nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio than normal cells. Examples of hyperplastic responses include nodular proliferations within the parenchyma of the prostate (Fig. 2-3), liver, and pancreas (Fig. 2-4).

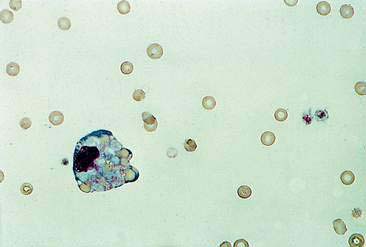

CYSTIC MASS

Cystic lesions contain liquid or semisolid material. The low-protein liquid usually contains a small number of cells. These benign lesions may result from proliferation of lining cells or tissue injury. Examples include seroma (Fig. 2-5), salivary mucocele, apocrine sweat gland cyst, epidermal/follicular cyst, and cysts associated with noncutaneous glands such as the mammary gland or prostate (Fig. 2-6).

INFLAMMATION OR CELLULAR INFILTRATE

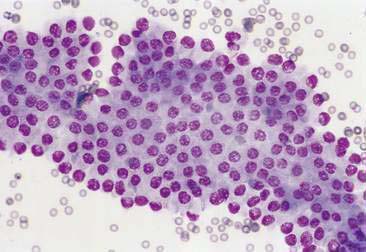

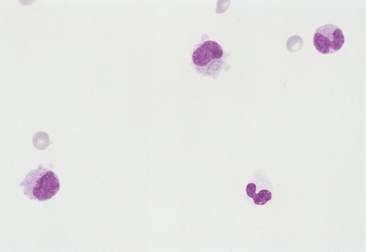

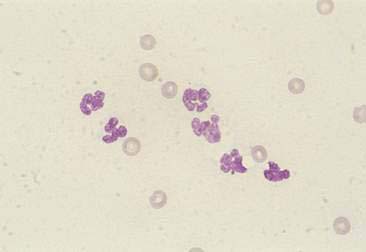

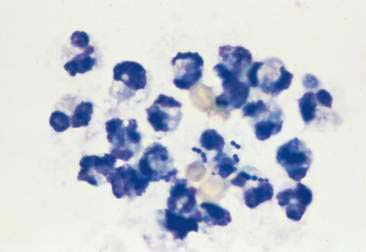

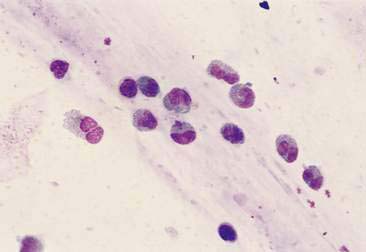

Purulent or suppurative lesions contain greater than 85% neutrophils; they are then classified by the presence or absence of degeneration affecting the neutrophil. Nondegenerate neutrophils are morphologically normal and predominate in relatively nontoxic environments such as immune-mediated conditions, neoplastic lesions (Fig. 2-7), and sterile lesions caused by irritants such as urine and bile. Degenerate neutrophils display nuclear swelling and decreased stain intensity termed karyolysis (Fig. 2-8), indicating rapid cell death in a toxic environment (Perman et al., 1979). Increased nuclear staining with coalescence of the nucleus into a single round mass and an intact cellular membrane characterizes pyknosis (Fig. 2-9), a slow, progressive change often within a relatively nontoxic environment. An end stage of cell death, termed karyorrhexis, may be seen cytologically as the result of pyknosis of hypersegmented nuclei (Fig. 2-10). Degenerate neutrophils predominate in bacterial infections, particularly gram-negative types. Under septic conditions, bacteria may be found intracellularly (Fig. 2-11).

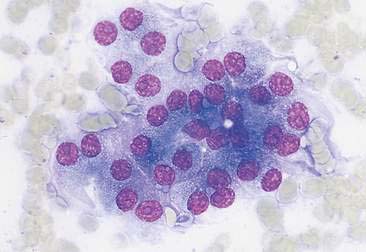

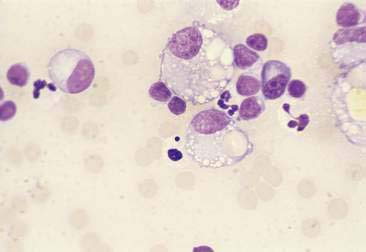

Histiocytic or macrophagic lesions contain a predominance of macrophages, suggesting chronic inflammation (Fig. 2-12). In granulomas, activated macrophages that morphologically resemble epithelial cells are termed epithelioid macrophages. These cells may merge to form giant multinucleated forms (Fig. 2-13). The granulomatous lesions are often associated with foreign body reactions and mycobacterial infection.

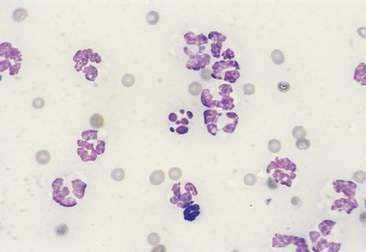

Pyogranulomatous or mixed cell inflammatory lesions contain a mixture of neutrophils and macrophages (Fig. 2-14) that may include increased numbers of lymphocytes or plasma cells. This type of inflammation is often associated with foreign body reactions, fungal infections, mycobacterial infections, panniculitis, lick granulomas, and other chronic tissue injuries.

Eosinophilic lesions contain greater than 10% eosinophils in addition to other inflammatory cell types (Fig. 2-15). They are seen with or without mast cell involvement. This inflammatory response is associated with eosinophilic granuloma, hypersensitivity or allergic conditions, parasitic migrations, fungal infections, mast cell tumors, and other neoplastic conditions that induce eosinophilopoiesis.

Lymphocytic or plasmacytic infiltration is often associated with allergic or immune reactions, early viral infections, and chronic inflammation. The lymphoid population is heterogeneous, with small or intermediate-sized lymphocytes and plasma cells mixed with other inflammatory cells (see Fig. 2-14). A monomorphic population of lymphoid cells without other inflammatory cells present suggests lymphoid neoplasia.

RESPONSE TO TISSUE INJURY

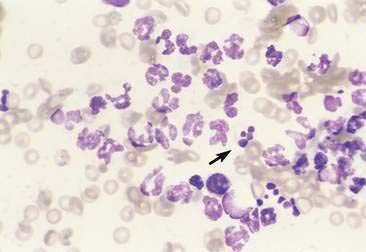

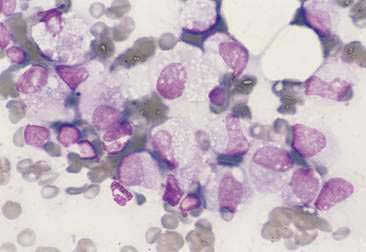

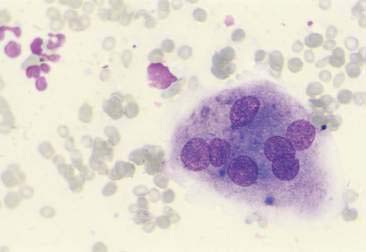

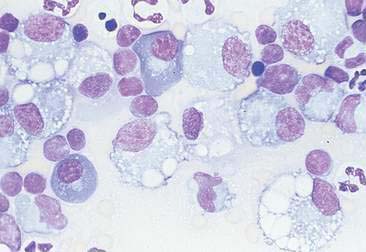

Hemorrhage that is pathologic can be distinguished from blood contamination encountered during the cytologic collection. Blood contamination is associated with the presence of numerous erythrocytes and platelets. Acute hemorrhage is associated with engulfment of erythrocytes by macrophages termed erythrophagocytosis (Fig. 2-16). Chronic hemorrhage is associated with active macrophages containing degraded blood pigment within their cytoplasm—for example, blue-green to black hemosiderin granules (Figs. 2-17 and 2-18) or yellow rhomboid hematoidin crystals (Fig. 2-18). Hemosiderin represents an excess aggregation of ferritin molecules or micelles. This form of iron storage becomes visible by light microscopy and stains blue with the Prussian blue reaction. Hematoidin crystals do not contain iron although they are formed during anaerobic breakdown of hemoglobin such as may occur within tissues or cavities. Hematomas often contain phagocytized erythrocytes if the lesion is acute, or hemosiderin-laden macrophages if the lesion is chronic.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree