Chapter 19 Rhinoscopy

Rhinoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Nasal Diseases, Transnares Curettage for Palliation of Malignant Nasal Obstruction

Rhinoscopy is an invaluable component of the nasal workup. Rhinoscopy is used in conjunction with diagnostics such as blood work, thoracic radiographs, skull radiographs, and skull computed tomographic (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It provides visualization of the nasal cavity, choanae, nasopharynx, and in some patients, the frontal sinuses. Chronic, unrelenting nasal disease is a frustrating problem in dogs and cats, and the primary disease can often be difficult to diagnose.1,2 Rhinoscopy is useful for both diagnostic and therapeutic case management and reduces or eliminates the need for rhinotomy in most instances. Rhinoscopy is the final component of the nasal workup. A sequential diagnostic approach is imperative, and history taking, signalment, and a physical examination are the building blocks. Nasal disease causes a variety of symptoms.

Equipment

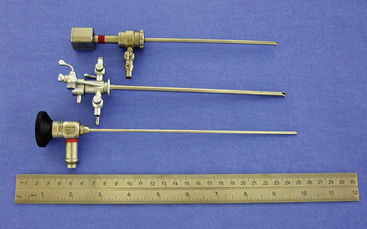

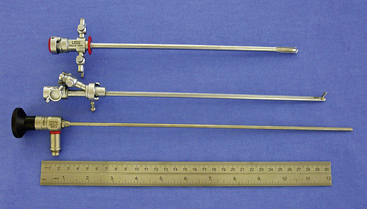

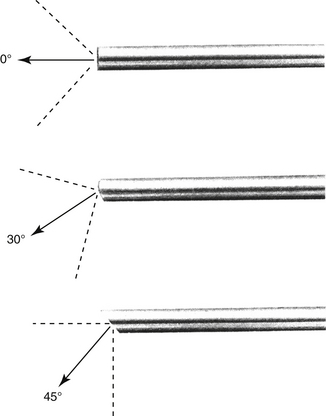

There are many equipment options available for direct visualization of the nasal cavity. The most effective tools are rigid telescopes with operating sheaths capable of irrigation and instrument passage within all nasal cavity regions. Otoscopes are only useful in nasal disease evaluation within the most rostral nasal compartment. Although preferred by some clinicians, flexible endoscopes are rarely needed and provide no additional diagnostic or therapeutic benefit to the clinician. Rigid endoscopes are the main tools used in rhinoscopy. Two rigid endoscope sizes are commonly used in small animal rhinoscopy. The 1.9- and 2.7-mm 30-degree visual field endoscopes can be used to adequately evaluate most cats and dogs the clinician will encounter in clinical practice. In cats and small dogs less than 10 kg, the 1.9-mm 30-degree integrated endoscope is preferred (Figure 19-1). In patients more than 10 kg, a 2.7-mm diameter multipurpose endoscope with a triport cystoscopy operating sheath is preferred (Figure 19-2). Some clinicians prefer using the arthroscopy sheath with the 2.7-mm scope as it has a slightly smaller working diameter but a greater flow rate when high irrigation is needed (Figure 19-3). The integrated scopes and operating sheaths generally have a parallel biopsy channel and two additional 90-degree channels with stopcocks for irrigation and suction. The arthroscopy sheath has only a single 90-degree channel for irrigation and is more than adequate in most instances because the biopsy and suction ports are seldom needed for their stated uses. The working length of these two scopes enables adequate visualization of the choanae and the nasopharynx in all but the largest of dogs. In giant breeds, a 4.0-mm diameter 30-degree visual field endoscope with a modular cystoscopy operating sheath is recommended for complete rhinoscopic examination (Figure 19-4). Angled visual field endoscopes require some clinician adaptation but when used properly allow for a much greater rotated hemispheric view with reduced traumatic leverage compared with 0-degree visual field scopes (Figure 19-5). This is a clinician preference, and either scope can be used on a daily basis to perform complete rhinoscopy safely. The chief advantages of rigid endoscopes are in their ability to provide reliable spatial orientation, high-flow irrigation, and the physical leverage used in different rhinoscopic techniques and to facilitate diagnostic biopsy.

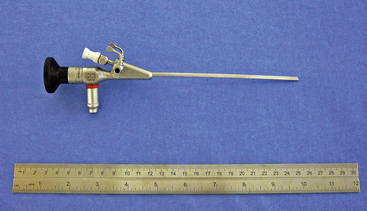

Figure 19-1 Karl Storz model No. 27030BA 1.9-mm 30-degree visual field integrated rigid endoscope.

(Photo courtesy of Karl Storz GmbH & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany.)

Evaluation of the Patient with Nasal Disease

History and Signalment

Nasal discharge characteristics are often nonspecific because serous, mucopurulent, and overt epistaxis can be seen with any type of nasal disease depending on the stage and duration of the problem. Primary epistaxis should suggest potential hypertension, tick-borne vasculitis, or coagulopathy. These should be investigated by the clinician before rhinoscopy. Bilateral signs occur most often with inflammatory conditions. Anatomic defects such as cleft palates can cause recurring rhinitis but should be easily identifiable without specialized diagnostics. Although rare, ciliary dyskinesia should be considered in the very young dog with recurrent bilateral mucopurulent rhinitis. Unilateral signs are often associated with foreign bodies, fungal infections, and tumors. Prior responses to an antibiotic, antiinflammatory, or antihistamine are nonspecific observations because most significant nasal cavity disease is complicated by a secondary bacterial infection, local inflammation, and reflexive mucus production. Inflammatory rhinitis, nasopharyngeal polyps, foreign bodies, and fungal infections tend to occur more in younger to middle-aged patients. Tumors tend to be more prevalent in the middle-aged to geriatric populations. Seasonal or geography-associated symptoms tend to predict allergic or inflammatory conditions (Box 19-1).

Physical Examination

External evaluation of the nose and nasopharynx begins with examination of the nostrils and face. The external nares should be checked for the character of discharge and ulceration of the epithelium. There is a distinct appearance of the nostril in animals with fungal rhinitis that includes ulceration and hypopigmentation. Hold the mouth closed with one hand, and close off one nostril with the other. Unilateral or bilateral obstruction can be determined with this maneuver. Animals with obstruction become frantic until they can open their mouths and breathe. If air movement is normal, suspect a generalized rhinitis or possibly a systemic disorder causing nasal symptoms. Epistaxis with normal movement of air through both nostrils should raise a red flag. Epistaxis can be unilateral or bilateral and can occur without primary nasal disease. In animals without obvious obstructive nasal disease, a coagulopathy, tick-borne vasculitis, or hypertension must be ruled out before general anesthesia and rhinoscopy are pursued. Fundic examinations are recommended in all patients with epistaxis. Palpate the face to check for asymmetry or bony defects in the skull. Destruction of bone indicates a neoplastic process. Pain can be seen with erosive neoplasms but is also seen with fungal rhinitis and peracute sinusitis. If the patient allows, examine the oral cavity, teeth, gums, and hard and soft palates both visually and through palpation. Erosion of the hard palate or ventral deflection of the soft palate by a lesion is sometimes visible or palpable during oral examination. Severe dental disease can cause rhinitis or overt oronasal fistulae typically in geriatric small to miniature dog breeds. Significant gingival recession, overt cavities, and loose teeth should prompt consideration of nasal disease of dental origin. Retropulsion of both eyes should be similar. A decrease in caudal movement of one eye indicates a periorbital, orbital, or retrobulbar swelling. Evaluate the movement of air through both nostrils.

Prerhinoscopic Clinical Pathology

A complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, urinalysis, prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and chest radiographs are recommended before rhinoscopy in all patients. In at-risk breeds, either a Von Willebrand’s factor analysis or buccal mucosal bleeding time is recommended. If epistaxis without obstruction is present, tick serologic analysis and a blood pressure measurement is indicated. Fungal serologic analysis is indicated in specific cases that are determined by geographic location and clinical suspicion. Negative fungal serologic results do not always rule out a particular fungal infection. Specific fungal serologic and polymerase chain reaction tests will have variable specificity and sensitivity with respect to the detection of specific fungal infections and should be assessed at the interpretation of results.3,4 Further steps in the diagnostic workup require general anesthesia.

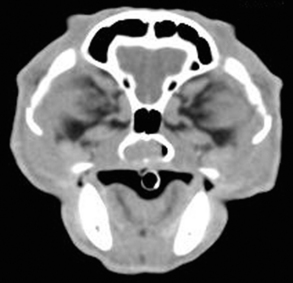

Radiography

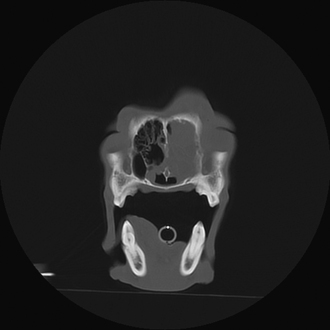

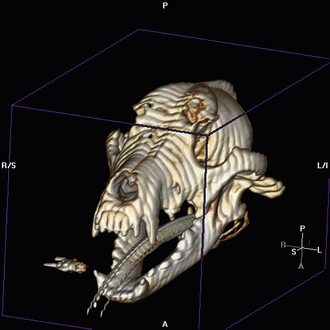

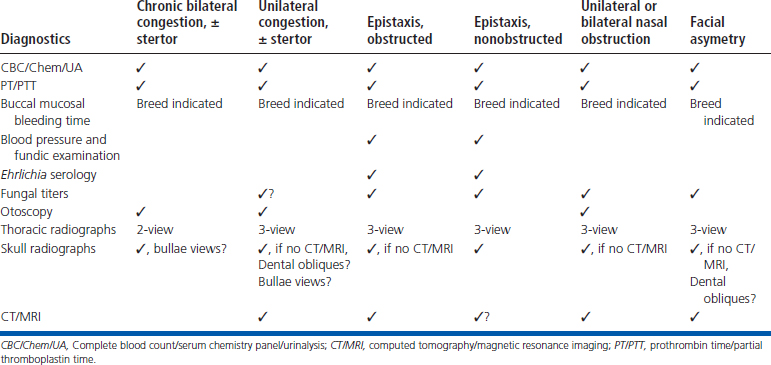

Radiographic imaging or CT is always performed before rhinoscopy. Rhinoscopic iatrogenic hemorrhaging and irrigation fluid used during the procedure will distort tissue and create fluid densities that can influence the findings in any radiographic study. Nasal radiographs can be performed in most hospitals and, with practice, can be very useful in the localization and characterization of nasal and nasopharyngeal disease.5 Nasal radiographs require general anesthesia and special patient positioning. Most commonly performed are 30-degree beam-angled open-mouth ventrodorsal and straight lateral views. The open-mouth view provides a complete, symmetrical image of the nasal cavity without superimposition of the mandible. Tumors typically show asymmetrical opacities and turbinate destruction (Figure 19-6). Turbinate destruction is also seen with fungal rhinitis. The straight lateral view allows evaluation of the nasopharynx and frontal sinuses (Figure 19-7). Further study of the frontal sinuses is achieved with a rostrocaudal tangential view (Figure 19-8). This allows comparison of the left and right frontal sinuses as the cavities are superimposed on the lateral view. Dental films of the maxillary arcade are sometimes needed to rule out tooth root abscesses and oronasal fistulae. MRI and CT scans are becoming more commonly available and provide better detail of the nasal, nasopharyngeal, and sinus cavities and cranial vault anatomy compared with standard radiography.6,7 Advanced imaging via MRI and CT, although considered state of the art, assist in description and localization of diseased tissue but have not yet produced results specific enough to eliminate the need for rhinoscopy8,9 (Figures 19-9 through 19-11) (Table 19-1).

Figure 19-6 Canine open-mouth ventrodorsal view with right-sided destructive soft tissue mass; nasal osteosarcoma.

Figure 19-7 Canine tangential sinus view with right-sided frontal sinus soft tissue opacity; nasal osteosarcoma.

Anesthesia for Rhinoscopy

Although rhinoscopy is less invasive compared with rhinotomy, adequate preoperative neuroleptanalgesia, intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, and antiinflammatory treatments are recommended based on the patient’s preoperative evaluation. Preanesthetic nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be used with caution and forethought because of potential inhibitory effects of some agents on platelet aggregation, as well as other adverse primary and drug interactive secondary reactions.10 Alpha-2 agonists can cause significant hypertension11 and should be considered potentially disadvantageous when used in a procedure likely to induce significant epistaxis. Anesthetic induction and intubation should be performed promptly because patients with nasal obstruction cannot breathe when their mouths are closed following heavy sedation. Immediate airway protection via appropriate endotracheal intubation will also help to prevent aspiration of infected postnasal secretions. Anesthesia maintenance is often provided via gas inhalation because all patients are intubated. During rhinoscopy abrupt and forceful sneezing and nasopharyngeal reflexive movements can be observed even in the adequately anesthetized patient. These forceful movements can greatly affect procedural ease, as well as induce patient trauma and cause equipment damage. Bilateral nerve blockade at the level of the infraorbital foramen can greatly reduce the sneeze reflex, and a combination of lidocaine and bupivacaine is recommended in dogs and at reduced doses in cats. Intraoperative and perioperative, culture-guided antibiotic therapy is recommended because of the high incidence of secondary bacterial rhinitis in the patient with nasal disease. Endotracheal tube cuff evaluation should be rechecked before any flushing because of the potential for iatrogenic flushing or aspiration of infected nasal secretions into the lungs.

Technique: Rigid Antegrade Rhinoscopy

Patients are placed in a sternal recumbent position. The cuffed endotracheal tube is secured to the mandible. A rolled towel is placed beneath the animal’s neck to point the muzzle in a ventral direction, and an oral speculum is placed to hold the mouth open (Figure 19-12). Fluid and tissue will then tend to run out of the nostrils and mouth rather than collect around the larynx. No gauze is stuffed in the oropharnx. This impedes the movement of fluid from the nasopharynx into the mouth. The animal’s front legs are pulled laterally or covered with plastic to prevent soiling. Again, endotracheal tube cuff evaluation should be rechecked before any flushing because of the potential for iatrogenic flushing or aspiration of infected nasal secretions into the lungs.

The scope is inserted at a slightly dorsal angle through the dorsal medial aspect of the nostril. Some prefer entering the ventral medial aspect of the nostril. Once past the nostril and the alar cartilage, the scope is straightened and advanced in a caudal direction. The nasal septum provides a source of anatomic reference. The three primary meatus should be examined. Mucosal changes, turbinate structure, and the nature of discharge are evaluated. Advance the scope slowly and passively to diminish bleeding. Allow the scope to follow the meatus with gentle pressure. When resistance is met or the field is obscured, pull the scope back gradually until visibility is restored. The goal is to examine as much of the nasal cavity as possible. Ease of examination is influenced by the size of the animal, breed, skull conformation, and the underlying disease.

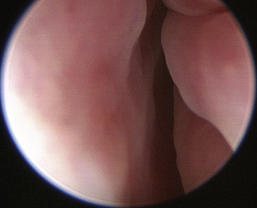

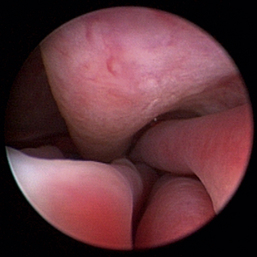

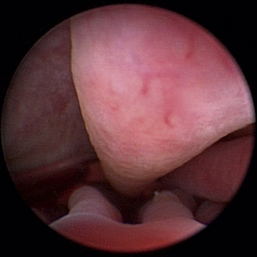

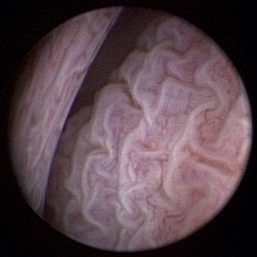

Normal turbinates have a smooth, pink-to-white surface and a spatial alignment that provides channels for the passage of air. The color varies and appears tan in the caudal nasal cavity. Turbinates come in different shapes and sizes, but the surface should be smooth. Ethmoid turbinates in the caudal nasal cavity will have a characteristic stippled or corrugated appearance (Figures 19-13 through 19-16). Ulcerations or various proliferations of the mucosa are indicative of disease. These changes are typically diffuse and accompanied by a lot of mucus. Mucus can be thin to purulent. Copious amounts can be flushed out of the nasal cavity to allow better visibility. The specific disease is determined by biopsy. After full examination of the nasal cavity, run the scope along the floor of the nasal sinus to the level of the choanae. Keeping the scope pointed in a ventral medial direction prevents inadvertent trauma or penetration of the cribriform plate. The index finger of the free hand can be used to follow the scope as it moves caudally over the hard palate; the surgeon can then palpate the scope through the soft palate when it moves into the nasopharynx. Some force is needed to complete this procedure and may result in increased bleeding.

Flexible fiberoptic endoscopes are preferred and utilized effectively by some clinicians, but we do not routinely use them for primary evaluations. Retrograde placement of these scopes behind the soft palate allows visualization of the nasopharynx, choanae, and caudal segments of the nasal passages. Flexible endoscopes can also be used in an antegrade fashion through the nostrils in some patients but are limited by the scope and patient size. Irrigation is limited with small fiberoptic scopes; biopsy instruments are diminutive at best, and the reliability of representative tissue collection should be questioned when this technique is used. The 2.5-mm fiberscope has a single channel used for both irrigation and instrument passage. When an instrument is passed, the irrigation flow is markedly reduced, drastically affecting visualization during biopsy collection. The spatial orientation estimation and direct visualization provided by flexible endoscopes is inferior when compared with rigid telescopes. In most cases, rigid telescopes can be passed through the nasal cavity, choanae, and into the nasopharynx, eliminating the need for flexible retrograde rhinoscopy.

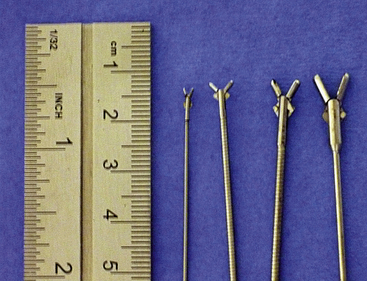

After the visual examination is completed, tissue samples are collected for culture and biopsy evaluation. Specialized endoscopic instruments are available for collecting samples through the biopsy channel of all scopes. Depending on the scope size and instrument channel, tissue samples may be very small, and the reliability of such minuscule samples should be questioned by the clinician (Figure 19-17). If endoscopic instruments are utilized, multiple (>12) samples should be collected to increase the accuracy of diagnosis. We recommend an alternate technique in which tissue samples are collected for biopsy evaluation by passing larger instruments parallel to the scope or retrieving samples without direct visualization based on lesion spatial approximation. With practice, the clinician should be able to spatially localize the diseased tissue (on the basis of the depth of penetration of the rigid scope, the angle of insertion, and sometimes visible transnasal illumination) and insert an instrument to the site large enough to attain grossly substantial tissues. The sample site is then reexamined with the scope after biopsy, and the process is repeated to the clinicians’ satisfaction. Even foreign bodies can be removed in this fashion. Focal, discrete lesions are uncommon in the patient with grossly symptomatic nasal disease. Direct visualization is recommended when these sites are sampled. Pass an alligator forceps or a cup biopsy forceps outside the scope until the instrument can be seen. This affords visualization of the biopsy site. It can be a tedious process, but the samples are adequate. Blind biopsy techniques do not diminish the value of rhinoscopy, and adequate tissue submission should be the ultimate diagnostic goal. Tissue samples are submitted for histopathologic analysis and aerobic bacterial culture in most cases. Mild-to-moderate, spontaneously resolving hemorrhaging is expected after the collection of samples for culture and biopsy evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree