Philippa O’Brien

Retained Fetal Membranes

In the mare, the fetal membranes are comprised of the allantochorion, amnion, and umbilical cord. Passage of these membranes during the third stage of labor usually occurs within 90 minutes of foaling and can be accompanied by uterine contractions and transient signs of abdominal pain.

Retention of the fetal membranes (RFM) or “retained placenta” is defined as partial or complete failure of release of the chorioallantois and is the most common postpartum complication in the mare. Most clinicians consider the membranes to be retained if they have not been passed in their entirety within 3 hours of foaling. Prompt veterinary attention is required, because delay in treatment increases the risk for potentially fatal sequelae, including toxic metritis and laminitis.

The incidence of RFM is reported to be 2% to 10% across all equine breeds, but up to 54% in draft breeds; this frequency is high, compared with other species, with reported incidences of 4% to 8% in cattle and up to 3% in women. Although some mares may have RFM following a normal gestation and foaling, risk factors include dystocia, cesarean section, induced parturition, abortion, preterm delivery, hydrops allantois, advanced maternal age, fescue toxicosis, and placentitis. Mares that have had previous episodes of RFM are also predisposed.

The main objective in treating a mare with RFM is to achieve expulsion or removal of the fetal membranes in their entirety, preventing the onset of metritis and endotoxemia and avoiding trauma to the endometrium so that the future breeding potential of the mare can be preserved. Early intervention can prevent development of life-threatening complications and substantial financial cost to the owner.

Pathophysiology

Equine placentation is diffuse, microcotyledonary, and epitheliochorionic. Microvillous attachments, which develop into microcotyledons, first form at about 40 days of pregnancy. Highly vascular chorionic villi interdigitate with the endometrial crypts, maximizing the surface area for attachment and nutrient exchange.

Release of the allantochorion is thought to be initiated by rupture of the umbilical cord after delivery of the foal; this causes collapse of the placental blood vessels and subsequent shrinkage of the microvilli, allowing them to slide out of the endometrial crypts. Endogenous oxytocin release stimulates rhythmic contraction of the uterus, starting at the tips of the horns and progressing toward the cervical opening. The presence of membranes within the cervix stimulates abdominal straining, often accompanied or followed by transient signs of pain. Foaling attendants must be vigilant at this stage to ensure that the foal is not inadvertently injured by the mare if she rolls or kicks out in discomfort.

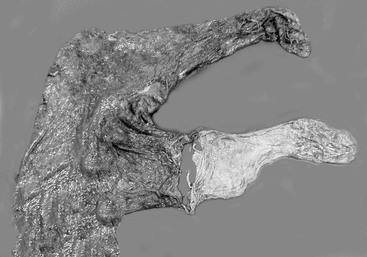

Separation of microvilli from the endometrial crypts begins at the gravid horn and is promoted by involution and contraction of the uterus and expulsive efforts from the mare. The horns of the allantochorion invaginate as they are released and pass through the ruptured cervical star. As the allantochorion passes through the vulval opening, increased weight of the membranes hanging down from the vulva encourages release of the nongravid horn. In normal circumstances, the allantochorion is passed intact, with the shiny gray allantoic surface outermost and remnants of the umbilical cord and amnion attached.

The causes of RFM have yet to be identified fully; investigators have suggested a combination of uterine inertia and hormonal imbalance, an assertion that is supported by the fact that administration of exogenous oxytocin resolves the condition in many mares.

Uterine inertia predisposes mares to RFM secondary to the absence of postpartum uterine contractions; affected mares often do not show the usual associated mild colic signs. Inertia may be a result of low calcium concentrations, overstretching of the myometrium (e.g., following twin pregnancy or hydrops allantois), or myometrial exhaustion associated with dystocia or advanced maternal age. In one study of draft mares, those with RFM had lower serum calcium concentrations than mares that did not have RFM, although the physiologically active ionized form of calcium was not measured in that report.

A recent publication describing 90 draft mares with RFM revealed that adhesion of the allantochorion to the endometrium was a much more common cause of RFM than uterine inertia. Adhesion occurred in 88% of cases of RFM, compared with 5.5% of cases caused by uterine atony, and was associated with histologic abnormalities of the allantochorion and endometrium. The most common histologic findings included fibrosis in the lamina propria of the chorionic villi and the stromal connective tissue. These results suggest that in draft mares, uterine inertia is a relatively minor cause of RFM, compared with placental adhesion; further investigation is warranted to compare findings in other breeds.

Periglandular fibrosis of the endometrium is thought to develop as a result of RFM per se or following excessive application of traction during attempts to remove the membranes; this may predispose a mare to repeated episodes of RFM and in some cases be detrimental to future fertility.

The most common clinical scenario involving RFM is that the tip of the nonpregnant horn of the allantochorion remains attached to the endometrium. This is probably related to differences in microvillar morphology: in the thicker, more edematous gravid horn, the villi are shorter, more blunt, and less interdigitated than they are in the nongravid horn, allowing them to detach more easily. Clinical observations indicate that the tip of the thin-walled nonpregnant horn of the chorioallantois is most likely to be torn off and retained when the remaining membranes are passed (Figure 171-1).

Mares that undergo dystocia and cesarean section are at high risk for developing RFM, partly because they are more likely to develop uterine inertia, but also because endometrial inflammation and hemorrhage caused by physical manipulations predisposes to chorionic adhesion. Mares in which foaling is induced and those that have preterm delivery or abortion are also at increased risk for RFM. This may be a result of abnormalities in the maturation processes of placental tissues and hormonal changes that usually occur in late gestation.

Toxic Metritis and Laminitis Syndrome

By far the most serious complication following RFM is development of toxic metritis. Acute metritis can develop secondary to autolysis of a retained portion of allantochorion or because sheared-off microvilli retained within endometrial crypts act as a nidus of infection. The autolytic material provides an ideal environment for rapid multiplication of bacteria introduced at foaling; bacterial invasion of the endometrium begins as early as 6 hours after foaling in susceptible mares. Organisms most commonly cultured are Streptococcus zooepidemicus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, with occasional anaerobes such as Bacteroides spp also isolated. Toxins from gram-negative bacteria cause inflammation of the endometrium, accumulation of uterine fluid, and delayed involution. The inflamed endometrium becomes friable, allowing systemic absorption of toxins and endotoxemia. Laminitis may then ensue, although the exact mechanisms remain unclear. It is thought that systemic absorption of endotoxin results in a procoagulative state and production of vasoactive mediators affecting the microcirculation in the hoof. Further research is underway investigating the effect of trigger factors acting at a cellular level in the digital lamellae. Laminitis in these cases is often severe and life threatening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree