11 Respiratory and Cardiac Disorders

Respiratory Problems

Dyspnea

Common causes of dyspnea are listed in Box 11-1.

Box 11-1 Causes of Dyspnea (Respiratory Distress)

Respiratory Disorders

Obstructive Disease

Nasal (only if patient does not breathe through mouth)

Chondromesenchymal hamartoma (cats)

Elongated/edematous soft palate

Extraluminal compression (tumor or granuloma)

Extraluminal compression (tumor, granuloma, hilar lymphadenopathy, left atrial enlargement)

Lower airways and pulmonary parenchyma

Pneumonia (viral, bacterial, fungal)

Hypersensitivity (allergic) lung disease

Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy

Useful Tests

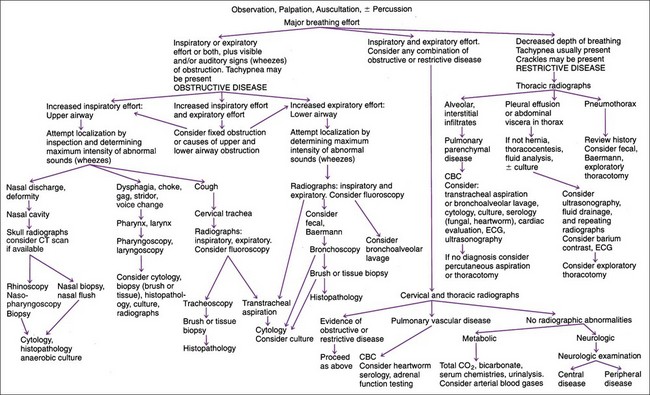

After the site of an abnormal breathing pattern has been localized by physical examination, tracheal and thoracic radiographs are typically the most useful next diagnostic step (Figure 11-1).

Transtracheal aspiration (TTA), bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), or transthoracic fine-needle aspiration (see subsequent sections) may follow if radiography suggests the need for cytologic analysis or culture of the lower airway, especially if coughing is present. Pharyngoscopy, nasopharyngoscopy, and laryngoscopy are useful in patients with upper airway obstruction. Tracheobronchoscopy is useful in tracheal and bronchial disorders, especially for diagnosing obstructive disease such as collapsed trachea, and it is mandatory in most pharyngeal and laryngeal abnormalities (see Figure 11-1). Pleural effusion is always an indication for fluid analysis (see Chapter 10). If dirofilariasis is suspected, a Knott’s test, filter test, or Dirofilaria immitis antigen (or antibody in cats) test is indicated (see Chapter 15). Although they rarely provide a diagnosis, fecal flotation and Baermann’s fecal analysis are inexpensive and noninvasive and can definitively diagnose respiratory parasites. Serologic testing for systemic mycoses (except histoplasmosis) may be useful in dogs (see Chapter 15). Tests for detecting Histoplasma and Blastomyces antigens in the urine are now available (http://www.miravistalabs.com) and might be better than serology.

Coughing, Including Hemoptysis

Common causes of coughing in dogs and cats are listed in Box 11-2. History is used first to eliminate self-limiting, contagious, infectious diseases. The owner should be carefully questioned to differentiate cough from gagging, because many owners confuse gagging with coughing. Gagging (not that after a coughing stint) would suggest nasopharyngeal or nonrespiratory disorders (i.e., oropharyngeal, esophageal, or gastrointestinal disease). Differentiation of a productive cough (e.g., bronchopneumonia) from a nonproductive cough (e.g., viral tracheobronchitis) and identification of abnormal breathing patterns (see Box 11-1 and Figure 11-1) are also helpful. Tracheal and thoracic radiographs are essential in patients with chronic cough, hemoptysis, or cardiovascular disease but are less useful in acute infectious tracheobronchial diseases unless secondary pneumonia is suspected. Radiographs can be used to diagnose but not reliably rule out a collapsed trachea. Fluoroscopy may be required to rule in or out tracheal collapse and is often needed for evaluation of extent of tracheal collapse if present. TTA or BAL (especially if combined with bronchoscopy) is often diagnostic of allergic disease, parasitic infections, or bacterial infections and supports a clinical diagnosis of certain chronic bronchial diseases (e.g., chronic bronchitis). Bronchoscopy is often needed to diagnose foreign body or obstructive disease. A CBC is seldom helpful unless marked eosinophilia (e.g., allergic or parasitic disease) is present. Fecal flotation and Baermann’s fecal analysis are rarely revealing but are indicated because they are easy and cost-effective. Arterial blood gas analysis is rarely diagnostic or cost-effective in coughing patients without dyspnea.

Box 11-2 Causes of Coughing in Dogs and Cats

Pharynx/Larynx

Infection (bacterial or viral)

Laryngeal paralysis (congenital or acquired)

Eversion of laryngeal saccules

Trachea/Lower Airway

Allergy (allergic bronchitis/asthma)

Bacterial (Bordetella bronchiseptica)

Parasitic (Filaroides spp., Oslerus osleri, Capillaria aerophilia)

Neoplasia (osteochondral dysplasia [osteochondroma])

Pulmonary Parenchymal Disease

Allergy (pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia)

Protozoal (Toxoplasma gondii, Pneumocystis carinii)

Degenerative disease (emphysema)

Neoplasia (primary or metastatic)

Nasal Discharge, Sneezing, and Epistaxis

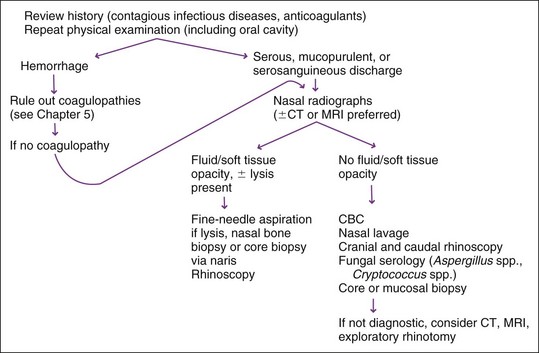

Nasal discharge and sneezing may be the result of primary nasal cavity disease or secondary to bronchopulmonary disease (e.g., pneumonia). Epistaxis may be the result of a primary nasal problem (e.g., neoplasia) or a systemic problem (e.g., coagulopathy). Common causes of these problems are listed in Box 11-3.

Box 11-3 Causes of Nasal Discharge, Sneezing, and Epistaxis in Dogs and Cats

Bleeding Disorders

Factor deficiency (congenital and acquired)

Thrombocytopenia (infectious and immune mediated)

Vessel wall (trauma and vasculitis)

Infections

Viral: distemper, parainfluenza, adenovirus type 2 (dogs); herpesvirus, calicivirus (cats)

Bacterial: including dental disease, chronic feline rhinosinusitis, Bordetella bronchiseptica (dog)

Rickettsial: Ehrlichia canis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever

When epistaxis occurs, evaluation for coagulopathy should be the initial diagnostic step (see Chapter 5). Radiography, but preferably computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the nasal cavity, is usually performed next (Figure 11-2); however, these studies may not be diagnostic in acute disease. If a mass lesion or bone lysis is identified, biopsy via the naris is indicated. Rhinoscopy to look for foreign objects is done following diagnostic imaging studies and can be performed while a patient is anesthetized for imaging. Direct examination may reveal adult Pneumonyssoides caninum. Serologic testing for nasal aspergillosis can be falsely negative and should not be relied on for a diagnosis (see Chapter 15). Direct examination of the nasal cavity (dorsal and ventral meatus) can be performed with rigid or flexible scopes (see under Rhinoscopy). The nasopharynx and posterior portion of the nasal cavity can be visualized with a dental mirror and penlight or more efficiently with a flexible endoscope. Endoscopy of the anterior portion of the nasal cavity in small dogs and cats is limited by the endoscope’s diameter. Nasal lavage is rarely diagnostic. Bacterial culture is not routinely recommended; interpretation is difficult because of the large normal bacterial population of the nasal cavity (see Chapter 15). Fungal culture for aspergillosis can have both false-positive and false-negative results (see Chapter 15). Cultures for fungi are generally more reliable if performed on nasal biopsy specimens rather than nasal cavity swabs. Nasal biopsy samples can be obtained with alligator-type clamshell instruments, with uterine or colonic biopsy forceps, or bone curettes (described later). If these procedures are not diagnostic and the condition persists, exploratory rhinotomy should be considered providing nasal CT or MRI has also been performed.

Nasal Radiography

Common Indications

Nasal radiography is indicated for chronic nasal discharge, epistaxis, severe acute undiagnosed sneezing, facial deformity, nasal obstruction, or pawing at the face or nose (see Box 11-3).

Computed Tomography

Advantages

CT requires less anesthetic time and provides much more detail than even well-positioned nasal radiographs.13,15 CT is excellent at determining extent of disease, finding “caverns” where aspergillosis has caused destruction and loss of turbinate structures, and it is far superior at finding tumors. CT readily detects involvement of the orbital region, frontal sinuses, calvarium, and cribriform plate in both aspergillosis and tumors.

Rhinoscopy

Nasal Biopsy

Advantage

Tissue can be obtained for histopathologic evaluation (and culture if indicated). Diseases other than neoplasia or fungal rhinitis that may be diagnosed by this method are (1) various idiopathic inflammatory diseases,8,14 and (2) primary ciliary dyskinesia (i.e., immotile cilia syndrome), although the latter requires electron microscopy to be definitive.

Procedure

If the animal’s coagulation status is questionable, a platelet count, mucosal bleeding time, activated clotting time, or prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) should be performed (see Chapter 5). Nasal biopsy is performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. The head should be positioned so that the nose points downward. The nasopharynx can be packed off as for nasal lavage. The biopsy instrument can be either small clamshell forceps for smaller patients or uterine or colonic biopsy forceps, or bone curettes, for larger patients. Direct biopsy of lesions may also be accomplished during rhinoscopy using biopsy forceps suitable for the scope. The distance from the naris to the medial canthus of the eye is marked on the biopsy forceps because this approximates the distance to the cribriform plate. The biopsy instrument is advanced with the jaws open slightly in advance of reaching the affected tissue; the jaws are then closed once the area of interest is penetrated, and the biopsy instrument with tissue is withdrawn. Caution: The biopsy instrument must not be advanced beyond the level of the medial canthus because of potential cribriform plate perforation.

Specimens are fixed in formalin (or other appropriate fixative if electron microscopy is desired) and submitted. A portion of the biopsy specimen can be submitted for fungal or bacterial culture if indicated (see Chapter 15). Impression smears can be made for cytologic examination, and the remaining tissue can be submitted for histopathologic evaluation. Bleeding from the naris after biopsy is expected but usually subsides within 30 minutes. Occasionally, bleeding is profuse, prolonged, or both, in which case the affected area can be packed with cotton-tipped applicator sticks dipped in dilute (1 : 10,000) epinephrine solution while the animal is maintained under anesthesia until bleeding stops. Alternatively, nasal tampons (Merocel Standard Nasal Dressing with drawstring; Medtronic Xomed, Jacksonville, FL) may be used. In extreme cases, ligation of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery can be life saving.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree