Chapter 26

Reptiles and Amphibians in Laboratory Animal Medicine

Reptiles and amphibians are found in a wide variety of institutional settings, ranging from corporate biomedical research facilities to veterinary colleges and herpetology teaching collections. Some amphibian species, such as the African Clawed Frog (Xenopus laevis) have become so commonplace that entire books are devoted to their husbandry and care in laboratory animal settings.1 African Clawed Frogs were originally used for pregnancy assays and toxicology research; more recent biomedical uses include oocyte harvesting for molecular biology research and, along with Xenopus tropicalis, developmental biology studies. In addition to Xenopus, commonly used laboratory species of amphibians include Axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum), American Bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus), Leopard Frogs (Lithobates pipiens), Tiger Salamanders (Ambystoma tigrinum), and Marine Toads (Bufo marinus). Axolotls have long been popular as animal models for limb regeneration studies; these have expanded to include cardiac and central nervous system regeneration. Bullfrogs and Leopard Frogs are commonly used in physiology laboratory instruction and in endocrinology, nociception, and infectious disease research. Tiger Salamanders and Marine Toads are used as models for studies involving neurology and ophthalmology. Most recently, wild and captive populations of amphibians have been used in environmental toxicology, endocrine disrupter, and chytridiomycosis investigations.

Funding Agency Requirements

In the 1980s, several federal agencies formed the Interagency Research Animal Committee (IRAC). Members of this group developed and published the U.S. Government Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research, and Training (U.S. Government Principles). These nine principles address federal laws, research relevance, appropriateness of species and numbers, consideration of alternatives, minimization of pain and distress, appropriate anesthesia, analgesia, and euthanasia, proper housing and veterinary care, personnel qualifications and training, and involvement of an objective body such as an animal care and use committee. Agencies that committed to adhere to these principles when conducting and sponsoring research include the Department of Health and Human Services (including the National Institutes of Health [NIH], Centers for Disease Control [CDC], and Food and Drug Administration [FDA]), the Department of Defense (DoD), Department of Agriculture (USDA), Department of the Interior (DoI), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Science Foundation (NSF).2

Individuals applying for grant funding from NIH and NSF must be from an institution that has a Public Health Service (PHS) Assurance. An institutional PHS Assurance follows the U.S. Government Principles, the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy),3 and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Guide).4 DoD funding requires compliance with the U.S. Government Principles and the Guide; NASA follows NASA Policy, PHS Policy, and the Guide; and FDA and EPA require compliance with Good Laboratory Practice regulations for projects focused on drug and product approval. Nonfederal granting agencies may request information on Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval or adherence to animal care guidelines on grant applications.5,6

Many professional organizations have standards for ethical conduct of research and criteria for publication in scientific journals. The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles (SSAR) Ethics Statement requires compliance with rules, including obtaining appropriate permits and IACUC approval for publication in the Journal of Herpetology and Herpetological Review.7 The American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists requires that IACUC approval be cited in the manuscript when submitting to Copeia.8 The Herpetologists League similarly requires documentation of IACUC approval in the cover letter and manuscript when submitted to Herpetologica and Herpetological Monographs.9 All three organizations collaborated on and published guidelines, Guidelines for Use of Live Amphibians and Reptiles in Field and Laboratory Research.10 Veterinary journals such as the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, American Journal of Veterinary Research, Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, and Comparative Medicine require compliance with applicable federal regulations and guidelines and evidence of IACUC approval.11–13 The Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine requests a statement of IACUC approval in the cover letter,14 and the Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians expects that IACUC approval has been obtained for experimental studies when submitting manuscripts to the Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery (Mitchell M: Pers. com., Mar 28, 2012).

Regulatory Oversight and Accreditation Guidelines

The USDA requires registration as a research facility if USDA-covered species are used in research and teaching. Registered facilities are subject to at least annual unannounced inspections by veterinary medical officers of the USDA. Significant uncorrected deficiencies in animal care and use programs can ultimately lead to fines and facility closure. At this time, USDA regulations cover only a defined subset of mammals. They are not applicable to reptiles and amphibians and will not be further included in this discussion. The U.S. Government Principles, PHS Policy, and Guide are much broader in scope and cover all vertebrate species. A division of NIH, the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) is charged with overseeing institutional compliance with the U.S. Government Principles, the PHS Policy, and the Guide.15 This is accomplished through several mechanisms, including reviewing and approving an institution’s PHS Assurance and conducting visits to the institution, if warranted. Conducting NIH-funded research activities without approval by an IACUC can result in an investigator having to return grant money. In addition to required federal oversight, many universities and research facilities are voluntarily accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International (AAALAC). AAALAC requires adherence to all applicable national, regional, and local legislation and uses the Guide as one of its three primary resources.16 AAALAC conducts triennial site visits to accredited institutions to review animal care and use programs.

The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

The Guide is used by many institutions when developing and implementing internal policies and procedures for vertebrate animal care and use. Although the term laboratory animal appears somewhat misleading, the Guide is careful to clearly define laboratory animals as all vertebrates used in research, teaching, and testing.17 The most recent edition of the Guide specifically addresses husbandry and care of aquatic species in research settings. It further explains that while it does not specifically discuss wildlife and aquatic species in natural settings, it does provide ethical considerations and general principles that are equally relevant to these circumstances.17

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

The aforementioned regulations and guidelines all require animal care and use program oversight by a body such as an IACUC. For PHS-assured institutions, there must be at least five members on the IACUC. Membership must include a laboratory animal veterinarian, a practicing scientist, a nonscientist, and a community member with no institutional affiliation.18 Animal care programs with reptiles and amphibians often find it advantageous to appoint IACUC members with experience in these groups of vertebrates. An alternative approach is to utilize consultants with expertise in the species being reviewed; these individuals can often provide valuable information that will enable the IACUC to make sound decisions on proposed animal use.

The IACUC is charged with several important functions, including review of the animal care and use program at least every 6 months.19 Components of this review include evaluation of the institution’s training program for researchers and research staff, animal care personnel, and the IACUC itself; the occupational health and safety program; the veterinary care program; security and disaster plan; deviations from standards in the Guide; and mechanisms for reporting concerns about animal welfare.

Collaborations between researchers at institutions are becoming quite common and can create some challenges for IACUCs. Whenever collaborations across institutions occur, there should be a formal written agreement addressing the responsibilities for oversight and IACUC review.20 These agreements help eliminate ambiguity and reduce redundancy in oversight.

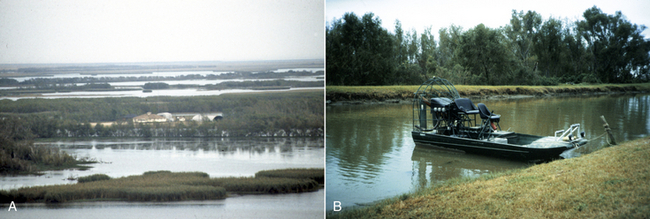

Another IACUC responsibility is inspecting animal facilities and use areas every 6 months. Although inspection of animal housing areas, surgery and procedure areas, and research laboratories is relatively straightforward, accessing remote field stations and research sites can be difficult (Figure 26-1). Accessibility is further complicated by the seasonality of field work. One solution for evaluating field research is for the IACUC to request videos or photographs of procedures conducted during the field season.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree