Chapter 19

A New Era of Amphibian Taxonomy

From activities ranging from teaching to veterinary practice, a taxonomy should accurately communicate the state of the art in knowledge related to both actual biodiversity and the phylogenetic relationships among species and groups (e.g., genera). A recent pulse of activity in amphibian systematics, spurred largely by technologic improvements in collecting and analyzing massive molecular data sets, has greatly increased the understanding of the relationships among and within the major groups; this new information has appropriately spurred efforts to revise the antiquated, misleading taxonomy of the last century or so. Given that novel taxonomic arrangements for long-familiar groups can be confusing and frustrating, this chapter endeavors to summarize in a user-friendly fashion the most recent taxonomic changes, especially as they relate to groups likely to be encountered by readers of this chapter. Ideally a taxonomy should reflect the phylogeny—the actual evolutionary history—of the creatures under consideration. Thus, this summary will hopefully be useful for keepers, curators, and veterinarians working with species that are poorly known or with which they are simply unfamiliar. Importantly, knowledge of the phylogenetic position of a species may allow one to extrapolate information relevant to other closely related species, genera, or from another family.

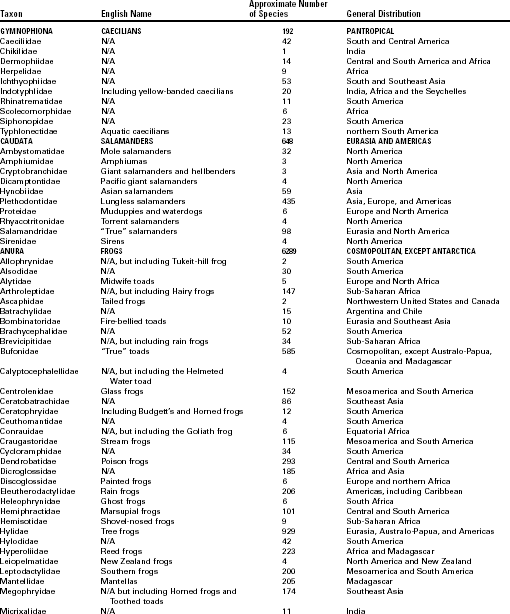

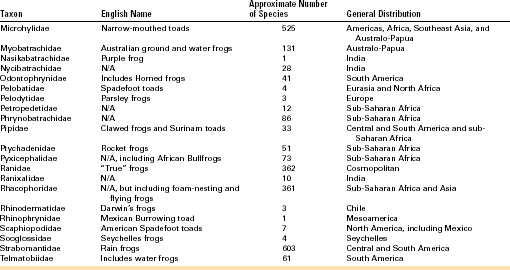

Because taxonomic monographs and treatments include exhaustive citations of all relevant literature and complete reviews of taxonomic changes and synonymies, those efforts will not be duplicated here and readers are referred to the original monographs. The current renaissance in amphibian taxonomy was spurred by a series of three monographs published by the American Museum of Natural History.1–3 The Amphibian Tree of Life3 was especially influential because it represented the first modern attempt to consider amphibian phylogeny in its entirety. Never claiming to be the last word on knowledge of amphibian phylogeny or taxonomy, it did proceed to frame and encourage a flood of subsequent articles that, considered together, have greatly increased knowledge of the history of Amphibia and represent major steps toward producing a taxonomy that is consistent with their history. Some important recent articles include treatments of the phyllomedusine frogs,4 hemiphractid frogs (formerly part of Hylidae),5 microhylid frogs,6 glass frogs,7 ranid frogs,8 bufonid frogs,9–12 and the terraranan frogs (the so-called eleutherodactylines, formerly included in Leptodactylidae).13 Additional recent efforts have informed the understanding of the broader groups such as caecilians14–16 and salamanders.17–19 Recently, Pyron and Wiens20 assembled virtually all of the molecular data produced by the mentioned series of articles (plus others not here listed) into a single massive analysis. Their study largely confirmed these previous more focused efforts and added some refinements to the ever-problematic assemblage of South American frogs formerly referred to “Leptodactylidae.” However, relationships within the large superfamily Hyloidea (including many families widely kept in captivity, such as the hylid tree frogs) were mostly poorly supported. Moreover, their phylogeny inexplicably retained an untenable nonmonophyletic taxonomy for Bufonidae and Ranidae. Table 19-1 lists a taxonomic summary of generally recognized families of amphibians, including approximate information on species-level diversity within each and geographic distribution.

TABLE 19-1

A Taxonomic Summary of Generally Recognized Families of Amphibians∗

∗Based on Frost DR, Grant T, Faivovich J, et al. The amphibian tree of life. Bull Am Museum Nat Hist 2006;297:1-370; Pyron RA, Wiens JJ. A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2011;61:543-583; and Frost DR. Amphibian species of the world: an online reference. Version 5.5. Electronic database available at http://research.amnh.org/vz/herpetology/amphibia/. Accessed January 31, 2011. Approximate numbers of species in each group and a very general description of geographic distribution are also presented (species counts are from Amphibiaweb.org).

Current generic-level taxonomy has not been emphasized nor summarized in this chapter because generic limits and species allocations are in constant flux, and, in the case of amphibians, considerable changes at this level can be anticipated in the upcoming years. For current information regarding generic allocations, the reader is referred to these frequently updated online references: The American Museum of Natural History’s Amphibian Species of the World at http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.php and The University of California’s Amphibiaweb at http://www.amphibiaweb.org/.

For species occurring in North America, the standard English and scientific names list cosponsored by all four of the major herpetological societies based in the United States is recommended.21 The most recent edition is available for free download by the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles at http://www.ssarherps.org/pages/comm_names/Index.php.

Readers working in institutions accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) should note that AZA follows the taxonomy of Amphibian Species of the World Web site22; however, this Web site is updated frequently, and it has not been standard for AZA institutions to update their records accordingly. The International Species Information System (ISIS) record-keeping system officially lists Frost23 plus the addendum by Duellman24 as their taxonomic standard. However, because both of those sources are quite outdated, it can be assumed that they now refer to the continuation of that same project, which now exists online in the form of Amphibian Species of the World.22 An additional useful Web site is the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List (http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/amphibians), which provides detailed information for every known species of amphibian regarding distribution, conservation status, and more, although this particular database is not intended to be a source of the most current taxonomic status of any species or group.

Phylogeny and Taxonomy of Amphibians

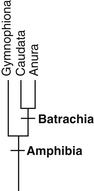

Amphibians are a distinct group of tetrapod vertebrates, and despite centuries of communications to the opposite, they are in no way “transitional” between fishes and other groups of tetrapods (e.g., reptiles). For the most part, referring a specimen in hand to one of the three major groups of amphibians (i.e., caecilians, frogs, and salamanders) has never been problematic. However, reconciling the relationships among these three groups has never been intuitive. This is because frogs and caecilians both have highly derived body forms while salamanders remain with what is frequently considered to be the generic tetrapod body plan. Some debate has occurred regarding the relationships among these three groups,25 but the arrangement shown in Figure 19-1 is now generally accepted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree