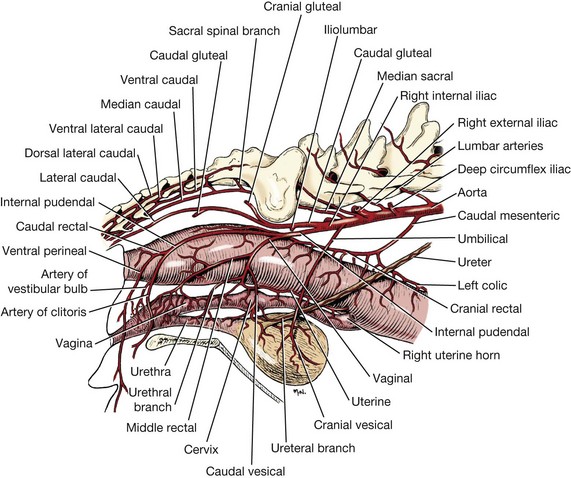

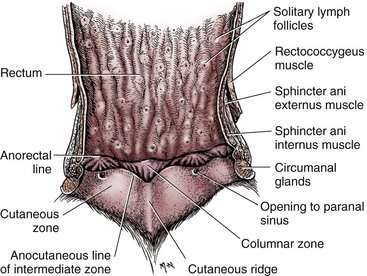

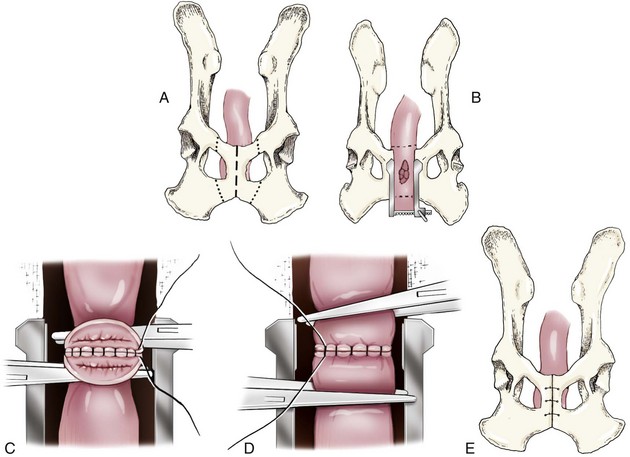

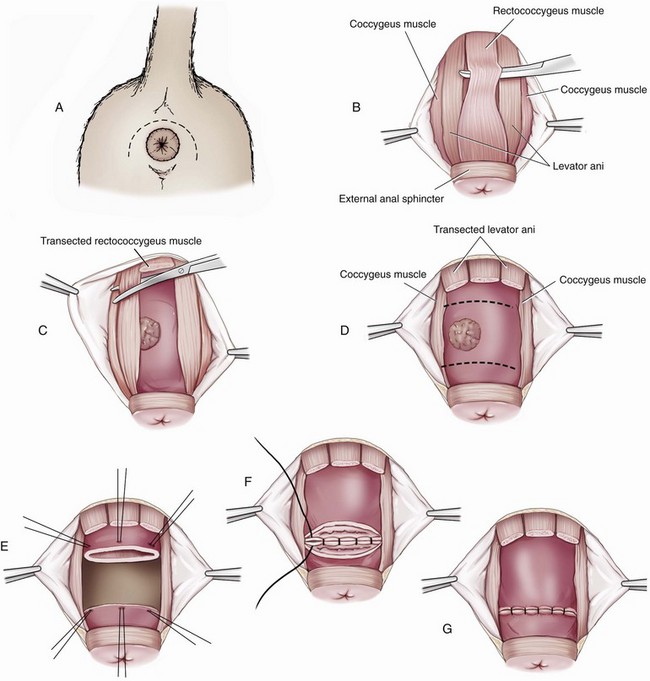

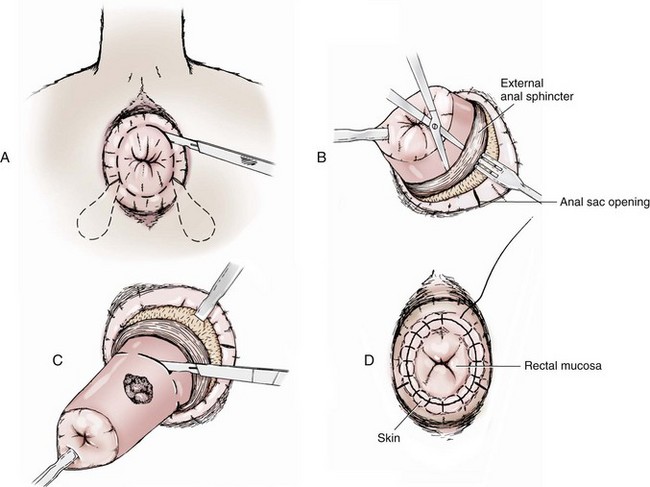

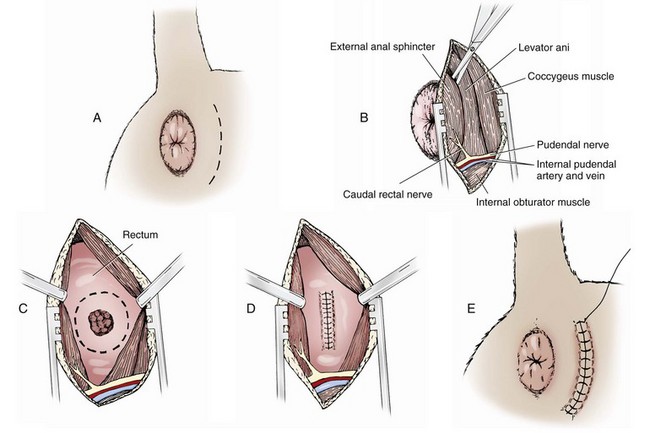

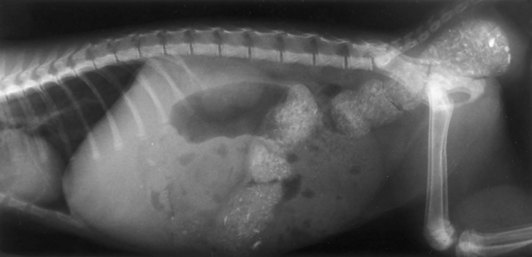

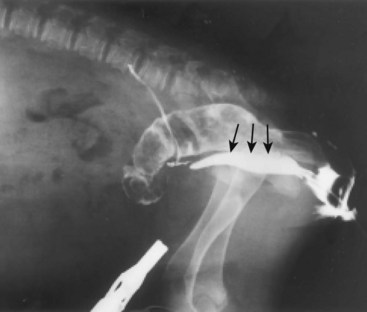

Chapter 94 The rectum begins at the pelvic inlet and ends ventral to the second or third caudal vertebrae at the beginning of the anal canal.192 The external anal sphincter muscle demarcates the caudal limits of the rectum. Most of the rectum is within the peritoneal cavity; however, a short segment continues retroperitoneally before it joins the anal canal. The cranial portion of the rectum is suspended from the sacrum by the mesorectum. The retroperitoneal portion of the rectum and anal canal are supported by the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm. The peritoneal reflection in dogs is located below the second coccygeal vertebrae and slightly more caudal in cats.91 The paired pararectal fossae are formed by the peritoneal reflection on either side of the rectum. The intraperitoneal portion of the rectum has four layers: mucosa, submucosa, a muscularis layer containing an inner circular and an outer longitudinal smooth muscle layer, and serosa.235,318 The retroperitoneal portion of the rectum lacks a serosal layer, which can have implications for surgical healing. In dogs, the cranial rectal artery appears to provide the majority of the blood supply to the terminal colon and rectum. The middle and caudal rectal arteries supply variable and relatively insignificant amounts87 (Figure 94-1). The intrapelvic rectum has a less adequate blood supply than the proximal rectum; therefore, the cranial rectal artery should be preserved during rectal surgery unless the intrapelvic rectum is resected. In cats, the intrapelvic rectum appears to be adequately supplied by the middle and caudal rectal arteries or other vessels.87 The anal canal is approximately 1 cm in length and is divided into columnar, intermediate, and cutaneous zones (Figure 94-2). The intermediate zone forms a distinct ridge called the anocutaneous line.79 Within the columnar and intermediate zones are tubular sweat glands known as anal glands.79 Anal glands in dogs consist of a secretory portion and an excretory duct system, which has saccular dilatations. The secretory epithelium and excretory duct system produce large amounts of neutral glycoproteins that have various terminal sugars, particularly The cutaneous zone of the anal canal is further subdivided into an internal zone, where the anal sacs are located, and an external zone. Both zones are rich in glandular tissue: true anal glands are present within the internal zone, and circumanal glands (perianal, hepatoid) glands are present in the external zone.11,135 The anal sacs are invaginations of the inner cutaneous zone. The internal anal sphincter muscle is the caudal thickening of the circular smooth muscle layer of the rectal muscularis.318 The external anal sphincter is a large, circumferential band of skeletal muscle that encourages maximum distention of the rectum for fecal storage while maintaining anal control and thus fecal continence. The anal sacs lie between these two muscles on either side of the anus. The anal canal is supplied from branches of the internal pudendal artery. The blood supply to the external anal sphincter is from the perineal arteries. The peritoneal reflection contains autonomic nerve fibers of the pelvic plexus that innervate the rectum and internal anal sphincter. The pelvic plexus is composed of parasympathetic fibers from the pelvic nerves and sympathetic fibers from the hypogastric nerves.91 Parasympathetic fibers of the pelvic plexus are excitatory to the rectum and inhibitory to the internal anal sphincter.318 Sympathetic fibers from the hypogastric nerves are inhibitory to the rectum and excitatory to the internal anal sphincter. The caudal rectal branch of the pudendal nerve supplies motor innervation to the external anal sphincter, and the perineal branch provides sensory innervation. Damage to the pudendal nerve may result in fecal incontinence. Control of rectal function, including storage and defecation, is through intrinsic and extrinsic systems. The intrinsic system, represented by the enteric nervous plexus, is located within the rectal wall. The extrinsic system is mediated through parasympathetic nerves. As the rectum distends, an inhibitory reflex is mediated through the enteric nervous plexus that effects rectal contraction and internal anal sphincter relaxation. Distension of the rectum eventually stimulates an extrinsic nervous mechanism, by way of parasympathetic fibers in the pelvic nerve, that initiates the defecation reflex.270 As the rectum contracts, tone in the internal anal sphincter is inhibited. Although these two reflexes complement each other, the intrinsic appears to be weaker than the extrinsic. As distension occurs, receptors within the anal mucosa send notice to the central nervous system, via the pudendal nerve, that defecation will be occurring. Conscious control is then evoked to facilitate or inhibit defecation. Relaxation of the external anal sphincter facilitates defecation, and voluntary constriction inhibits it. In cats, pelvic nerve stimulation can induce excitatory and inhibitory effects on the internal anal sphincter. Whereas low-intensity stimulation can elicit contraction of the sphincter, high-intensity stimulation relaxes it.31,38 Similar to dogs, the excitatory effects are thought to be a result of sympathetic nerve discharge from the hypogastric nerve to the internal anal sphincter.31 The excitability of smooth muscle is based on its resting membrane potential. Unlike other excitable tissues, resting membrane potential in gastrointestinal smooth muscle is not constant; instead, it oscillates over time in slow waves. These slow waves are generated by electrical pacemaker cells called the interstitial cells of Cajal. Processes from these cells form gap junctions between longitudinal and circular muscle cells that enable slow waves to be rapidly conducted to both muscle layers. In dogs, structural organization of the circular smooth muscle and distribution of the interstitial cells of Cajal change dramatically from the rectum to the internal anal sphincter.126 Differences in structural arrangement of smooth muscle and distribution of this specific cell type are thought to result in functional differences within this area. Patient Preparation and Antibiotic Therapy The goals of large bowel preparation include minimizing fecal flow during and immediately after the surgical procedure and significantly reducing bacterial content of the bowel. Because the majority of these procedures are elective, there is usually adequate time to prepare the bowel. Food is withheld or a low-residue, high-calorie diet is offered for approximately 24 to 48 hours before surgery. Some surgeons advocate administration of warm water enemas for up to 12 hours before surgery. Cleansing of the bowel may be necessary if endoscopy is going to be performed to determine the extent of the disease. Enemas should not be given the day of surgery to avoid leakage of liquefied fecal material into the surgical site. Enemas are contraindicated in patients with very large obstructive lesions because some enema fluid may be retained, increasing the chance of intraoperative contamination.317 Oral administration of GoLYTELY (polyethylene glycol and electrolytes) is very effective in cleansing the bowel. Two doses of GoLYTELY (40 mL/kg) are administered via nasogastric tube: one dose the night before colonoscopy and surgery and the second dose a few hours before colonoscopy and surgery.158 Some clinicians administer two doses, approximately 8 hours apart, via nasogastric tube the day before colonoscopy and surgery and a final dose a few hours before colonoscopy and surgery. In addition, a laxative such as magnesium sulfate may be administered 24 to 48 hours before surgery to enhance emptying. In addition to the GoLYTELY, an enema may be given a few hours before the procedure if only diagnostic colonoscopy is being performed. Alternatively, sodium phosphate tablets (Visicol or OsmoPrep) may be administered at a dosage of 0.25 to 0.3 tablets/kg followed by 25 mL/kg of appropriate fluids (orally, subcutaneously, or intravenously) with each dose. If vomiting occurs, the dose can be broken up into two or three smaller doses given 10 to 15 minutes apart. Because the patient may be systemically ill, administration of intravenous fluids may be beneficial to ensure that the patient remains well hydrated before surgery. In patients having surgery, cleansing of the bowel should be performed in conjunction with antibiotic therapy. Feces remaining after mechanical preparation contain a high concentration of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria that have the potential to cause a postoperative infection. Use of parenteral or enteral antibiotics has been advocated in dogs and cats to reduce the numbers of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria present during rectal and anal surgery.79,181,225,317 Prophylactic antibiotic therapy is particularly important in these cases because of the high risk of contamination and resultant infection. Infection in these cases may cause a significant amount of morbidity and mortality. It is important to acknowledge, however, that the use of antibiotics is not a replacement for strict aseptic surgical technique. Infection at the surgery site may increase collagenase activity in the rectal submucosa, resulting in decreased tensile strength and predisposing the patient to incisional dehiscence during the first 3 to 5 days after surgery.317 The ideal timing for prophylactic antibiotic therapy is still debated in human medicine. Additionally, although the chosen antibiotic(s) should have anaerobic and aerobic spectrum of action, no gold standard has been determined. In humans, oral antibiotic therapy is initiated within 24 hours before surgery to promote bowel sterilization, and parenteral antibiotics may be administered every 2 hours, beginning within 1 hour before surgery, so that peak concentrations are present in the wound when tissue contamination is most likely to occur. These concentrations should be maintained until closure. One study found that the greatest reduction in infection rate occurred when antibiotics were administered between 16 and 60 minutes before surgical incision.85 In another study evaluating prophylactic antibiotic use in biliary and gastrointestinal tract procedures, a single dose of a prophylactic antibiotic was sufficient if the operation was completed within 3 hours.260 For longer procedures, antibiotic coverage was extended for the duration of surgery. There was no value in continuing antibiotic administration beyond completion of the operation.260 In humans, cefoxitin and cefotetan have low toxicity; excellent activity against gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli; and good activity against some gram-positive cocci and a variety of anaerobic bacteria, including Bacteroides fragilis.45 Second-generation cephalosporins are more effective against some pathogens and are often preferred over first-generation cephalosporins for colorectal procedures.99 Because of their broad spectrum of activity and ability to achieve appropriate blood levels quickly, cephalosporins are also recommended in dogs and cats. Second-generation cephalosporins (cefoxitin, cefotetan, cefmetazole) or a combination of gentamicin and cefazolin may be administered intravenously 1 to 2 hours before possible surgical contamination so that peak concentrations are present at the surgery site.79,317 Parental antibiotics should be administered only during the perioperative period; use of parenteral antibiotics beyond the immediate postoperative period (24 hours) has not been shown to be beneficial unless infection is present.247,317 Enteral antibiotics can also be used to decrease the concentration of bacteria at the time of surgery. Oral antibiotics of choice include a combination of neomycin and metronidazole. Neomycin has a broad spectrum of activity against aerobic bacteria, and metronidazole is effective against anaerobic bacteria. Because most of the metronidazole is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, it also provides systemic protection against anaerobes. Other antibiotic combinations include neomycin and erythromycin or metronidazole and cefazolin. Oral antibiotics have little effect if mechanical cleansing of the bowel has not been performed before antibiotic therapy.162,317 Elimination of stool and decrease in gastrointestinal transit time occur with mechanical cleansing; it is hypothesized that this improves the concentration of intraluminal antibiotics.202 In patients with rectal neoplasia, the ventral approach can be combined with an abdominal exploratory for inspection and biopsy of all possible metastatic lesions (Figure 94-3). The ventral midline abdominal incision is extended caudally to the level of the pubis or, if removal of the pubis is necessary, to a point just cranial to the vulva or scrotum. After exploration of the abdominal cavity, the distal colon and rectum are carefully palpated to determine the extent of the lesion. If exposure to the pelvic canal is necessary, a pubic osteotomy, a pubic symphysiotomy, or a pubic and ischial osteotomy can be performed. To perform a pubic symphysiotomy, an incision is made in the aponeurotic attachment of the adductor muscles over the pubic symphysis. The pubis and ischium are divided on the midline with an oscillating saw or an osteotome and mallet, and the bone ends are distracted with self-retaining pediatric Finochietto retractors. For greater exposure, a pubic osteotomy or pubic and ischial osteotomy is performed.49,333 Through a caudal midline incision, the adductor muscles are exposed over the pubis and elevated to the lateral limits of the obturator foramina. Holes are predrilled in the pubis on both sides of the proposed osteotomy sites for later reattachment of the bone. The pubis is then cut on both sides, 2 to 3 mm medial to the lateral limit of the obturator foramina. A final cut is made caudally in the midline at the junction with the ischium or bilaterally through the ischia. Periosteum and soft tissues should be removed from one side of the pubis, allowing it to hinge on the remaining attachments. Complete detachment of the ischial–pubic segment may increase susceptibility of the avascular bone to infection and sequestration.212 Performing a pubic osteotomy alone without the bilateral ischial osteotomy provides restricted access to the pelvic canal and only allows exposure to more cranial intrapelvic lesions. The colon and rectum are aligned by placing simple interrupted sutures at the mesenteric and antimesenteric borders of the bowel. These sutures can be used as stay sutures to help with manipulation of the bowel ends while other sutures are being placed. A single layer of single interrupted approximating sutures through all layers of the bowel is recommended. This pattern provides good apposition, ensures adequate blood supply to healing edges, and does not significantly narrow the bowel lumen.181 The preferred suture materials for this anastomosis are synthetic absorbable materials such as polydioxanone or polyglyconate (Maxon). Because of its unpredictable rate of absorption, rapid loss of tensile strength, and potentiation of inflammation and infection, chromic gut should be avoided.317 Polypropylene is recommended when delayed healing is a concern. For dogs and cats, 3-0 or 4-0 monofilament suture is recommended. Sutures should be placed 3 mm apart and 2 to 4 mm from the incised rectal edge.181 If tension across the anastomosis is anticipated, a two-layer appositional closure can be used. The first layer incorporates the mucosa and the submucosa with the knots placed intraluminally; the second layer incorporates the serosa, muscularis, and submucosa. Alternatively, an end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) stapler can be used. After the anastomosis is complete, the Doyen forceps are removed, and the site is examined for any leakage. The abdomen and pelvic canal are lavaged with sterile saline solution, and clean instruments and gloves are used for closure. If a pubic symphysiotomy has been performed, the pubis is reattached with two or three orthopedic wires. If a pubic osteotomy has been performed, soft tissues are reattached by passing sutures through holes drilled through the pubis; the pubic osteotomies can then be realigned with orthopedic wire. Use of polydioxanone suture to appose the osteotomies has also been described.333 A dorsal approach (Figure 94-4) has been described for resection of tumors of the midrectum.122,186 The animal is placed in a padded perineal stand with the tail elevated, and a purse-string suture is placed around the anus. An inverted U-shaped incision is made between the anus and tail, extending from the tuber ischium on one side to the other. Subcutaneous fat is dissected, and perineal fascia incised. The rectococcygeus muscle, dorsal surface of the rectum, and external anal sphincter muscle are then visible. The paired rectococcygeus muscles are transected near their attachments at the ventral surface of the coccygeal vertebrae to improve exposure of the dorsal pelvic canal and rectum. Blunt dissection is continued between the external anal sphincter and levator ani muscles. To improve exposure, the levator ani muscles can also be transected. Care should be taken to prevent damage to the pelvic nerve plexus that fans along the lateral surface of the rectum in the peritoneal reflection.79 Damage or resection of this plexus can result in fecal incontinence. After exposure of the rectum, stay sutures are placed circumferentially cranial and caudal to the proposed resection site. The cranial sutures prevent retraction of the proximal rectal segment. The distal transection site is located 1 to 2 cm cranial to the anal sphincter. Resection and anastomosis is performed with suture or an EEA stapler.83 With a sutured anastomosis, the ventral rectum is sutured first with knots placed within the rectal lumen; knots are placed extraluminally when anastomosing the lateral and dorsal portions. After completion, the anastomosis is checked for leaks and excessive tension, and the area is lavaged with warm sterile saline. Muscles that have been transected are reapposed. Two small Penrose drains can be placed into the ischiorectal fossa with exit points ventrolateral to the anus or continuous suction drains can be inserted through dorsal skin incisions into the site. Drains should not be placed in direct contact with the anastomosis because rectal healing may be affected. Closure is completed with placement of subcutaneous and skin sutures and removal of the anal purse-string suture. Drains are removed after drainage is minimal and fluid is clear or serosanguineous. A rectal pull-through technique (Figure 94-5) can be used to remove abnormal tissue in the middle or caudal rectum. The patient is positioned in sternal recumbency on a padded perineal stand. If the tumor is present in the anal canal, the initial incision is made in the skin adjacent to the anal opening. Because the anal sac openings will be included in this incision, anal sacculectomies are performed. Removal of the anal sphincter will result in incontinence. If the external anal sphincter is not involved, the initial incision can be made just proximal to the anocutaneous junction, leaving a 1.5-cm cuff of rectum and avoiding the anal sac ducts. As the incision is extended 360 degrees, stay sutures are placed around the circumference of the rectum. To perform a transanal pull-through, the rectal wall is everted through the anus and stay sutures are placed. A full-thickness incision through the rectal wall is performed while preserving the distal rectal stump. Using blunt dissection and following transaction of the rectococcygeal muscle, the cranial rectum is mobilized and retracted caudally. Stay sutures are placed in the cranial rectal segment, and the affected segment of rectum is resected. Full-thickness colorectal amputation is performed. The normal cranial rectum is sutured to the distal rectal stump using an absorbable suture (2-0, 3-0 polydioxanone) in an appositional interrupted suture pattern.196 With the lateral approach, exposure is limited to one side of the rectum (Figure 94-6). Although rarely used, it may be appropriate for resection of a rectal diverticulum or rectocutaneous fistula or repair of a rectal laceration.79 A similar approach is used for perineal hernia repair. A curvilinear perianal incision, approximately 2 to 3 cm lateral to the anus, is extended from the tail base to the ischium. Dissection of the subcutaneous tissue exposes the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm. Fascia between the external anal sphincter and levator ani is dissected to expose the lateral surface of the rectum. Preservation of the caudal rectal nerve to the external anal sphincter is essential. After rectal resection or repair, the area is lavaged with sterile saline, and a drain is placed if contamination has occurred. Muscles are reapposed with absorbable suture to prevent herniation in the ischiorectal fossa, and the subcutaneous tissues and skin are closed routinely. After surgery, medical therapies are usually unnecessary in patients that have undergone minor resections with minimal contamination. A stool softener such as lactulose may decrease discomfort during defecation, and analgesics and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may reduce postoperative straining and pain. Patients that have undergone major rectal or anal resection may need more extensive therapy. Intravenous fluid therapy may be needed until the animal is eating and drinking and its electrolyte and acid–base abnormalities have been corrected. Analgesics are usually required for several days. Stool softeners can be continued for several weeks as needed. A bland, low-fat diet (rice, potatoes, pasta, chicken, and cottage cheese) is sometimes recommended after rectal surgery, with a gradual reintroduction of the animal’s normal diet.79 If the surgical procedure was considered clean, antibiotics are discontinued 2 to 4 hours after surgery. If considerable contamination occurred, a longer course of therapy is indicated. Patients with anal or rectal masses should be evaluated periodically for signs of recurrence, development of new lesions, or the presence of metastatic disease. Potential complications after anorectal surgery are numerous. The most significant complications include anastomotic dehiscence, infection, stricture formation, and incontinence. Disruption of the blood supply to the bowel ends, poor suture placement, or tension on the anastomosis may lead to anastomotic failure. Infection can occur secondary to dehiscence of the anastomotic site or with incomplete lavage and drainage of the area. Anastomotic failures and postoperative infections usually become apparent within 3 to 5 days after surgery. Strictures at the anastomotic site can occur because of excessive tension or with use of suture patterns that narrow the bowel diameter. Incontinence can occur if the pelvic plexus at the peritoneal reflection is disrupted during rectal resection or if the anal sphincter is removed. In one experimental study of healthy dogs, resection of 6 cm of the rectum, including the peritoneal reflection, through a dorsal approach resulted in incontinence.4 Animals that underwent transection alone or resection of 4 cm of the rectum defecated normally.1 Removal of the distal 1.5 cm of the rectum may also cause fecal incontinence even if the external anal sphincter is preserved.79 Interestingly, resection of more than 6 cm of the colorectum and peritoneal reflection, but preservation of 1.0 to 1.5 cm of the distal rectum, did not result in permanent fecal incontinence.196 The incidence of congenital abnormalities of the rectum and anus in dogs and cats is difficult to determine because many newborn animals with deformities are euthanized before ever being evaluated. In a recent study using the Veterinary Medical Database (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN), the incidence of congenital abnormalities of the rectum and anus in dogs was approximately 0.007%.313 Females were 1.79 times more likely to develop these conditions, and poodles and Boston terriers were predisposed.313 The cloaca is a common opening for the gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive tracts in developing embryos. Abnormal embryonic development of the cloacal region in puppies and kittens is thought to be responsible for congenital abnormalities of the rectum and anus. Veterinary patients presenting with anorectal abnormalities should be carefully evaluated for other anomalies because approximately one third of humans with anorectal abnormalities have anomalies of other body areas. Conditions that have been reported to accompany congenital anorectal abnormalities in dogs include vaginal abnormalities,147 tail malformations,164 a short colon,239 absence of anal sac ducts,185,239 and an incomplete or absent external anal sphincter.147,164 Atresia ani is the most frequently reported congenital rectal or anal anomaly in dogs. Most commonly, atresia ani is classified into four basic anatomic types.138,181 Animals with type I atresia ani have congenital stenosis of the anus. Animals with types II, III, and IV have varying degrees of rectal agenesis along with anal abnormalities. Animals with type II anomalies have persistence of the anal membrane, and their rectums end immediately cranial to the imperforate anus as a blind pouch (Figure 94-7). In type III, the anus is also closed; however, the blind end of the rectum is situated farther cranially. In type IV, the anus and terminal rectum can develop normally; however, the cranial rectum ends as a blind pouch within the pelvic canal. Accessory structures in the anus are usually developed normally; an anal sphincter is present, and the anal sacs open to the exterior. If surgery is planned, sphincter function can be evaluated preoperatively by applying an electrical stimulus to the perineum269 or by pinching the vulva.128 Newborn puppies and kittens with types II, III, or IV atresia ani are clinically normal for the first 2 to 4 weeks of life and then become unthrifty, anorexic, or restless and develop abdominal enlargement.138 Defecation is absent and, for types II and III, a dimple can be seen at the site of the closed anus. Vomiting and dehydration may eventually develop. Depending on the level of rectal atresia, perianal bulging may be present. Abdominal radiographs often determine the degree of colonic distension and position of the terminal rectum within the pelvic canal because gas may accumulate in the colon and rectum. Elevation of the animal’s hind end during a lateral abdominal radiograph or horizontal-beam radiography has been suggested to allow gas to migrate into this location.53,128,266 Congenital anorectal abnormalities are uncommon; as a result, limited information currently exists in the literature regarding clinical experience with these patients. Because many patients are typically small and in poor body condition, they are often at an increased anesthetic and surgical risk. Much of the literature suggests that the prognosis for these patients is poor and surgical mortality high. In a recent report evaluating congenital anorectal abnormalities in six dogs, follow-up during a period of 1 to 5 years revealed that four of six dogs were able to pass feces normally.233 Repeated procedures may be necessary after bougienage of type I atresia ani because of anal stricture formation with subsequent tenesmus, dyschezia, and constipation. Because the diagnosis is often delayed, chronic distension of the colon and rectum (i.e., megacolon) may result in irreversible damage to these organs. Young animals may have severe megacolon at the time of diagnosis; this complication may necessitate the need for a subtotal colectomy. Injury to the external anal sphincter or its innervation may result in temporary or permanent fecal incontinence. An additional anatomic abnormality that can be associated with atresia ani is a fistula between the urogenital tract and rectum. Development probably occurs because of failure of the urorectal septum to separate the cloaca completely into an anterior urethrovesical segment and a posterior rectal segment.290 The incidence of these conditions is unknown. Although no breed predisposition has been identified, in one report of five dogs with rectovaginal fistula and atresia ani, three were poodles.237 Although not proven, a heritable component of urethrorectal fistulas is presumed to exist in English Bulldogs.41,217 In females, the fistula connects the dorsal wall of the vagina or vestibule with the ventral portion of the terminal rectum, which often ends in a blind pouch.138,139 In males, fistulas develop between the rectum and urethra. Rectovaginal fistulas are commonly present in association with atresia ani type II abnormalities and occur more commonly in dogs than cats. Partial tail agenesis has also been reported in dogs in conjunction with rectovaginal fistula and atresia ani.237 The type of clinical signs in these patients depends on whether the rectal and anal canals are closed or stenosed and whether the fistula allows decompression of the colon and rectum. Typically, patients with rectovaginal fistula and atresia ani show few clinical signs while they are on a liquid diet.139 The mother cleans the common opening; thus, local irritation is initially minimal. If the fistula is wide enough to permit passage of solid feces from the vulva after weaning, the condition may remain undiagnosed for months. In patients with a urethrorectal fistula, the classic sign is leakage of urine from the rectum or urination from the urethra and anus simultaneously.41 Eventually, clinical signs in patients with either rectovaginal or urethrorectal fistula can include vulvar or perianal irritation, cystitis, dysuria, hematuria, pollakiuria, chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections, tenesmus, diarrhea, and megacolon.41,138,217 Struvite urolithiasis has also been diagnosed in conjunction with urethrorectal fistulas.217 The diagnosis and characterization of the fistulous tract are based on history, clinical signs, careful rectal examination, and positive-contrast radiography of the rectum or vagina (Figure 94-8).290,307 Positive-contrast retrograde urethrography is the best method for diagnosing a urethrorectal fistula.140 Contrast material can also be infused directly through the fistula or vagina; resulting studies may be helpful in determining the position of the tract. Voiding cystourethrography has also been described.90 These techniques can be used in conjunction with fluoroscopy. If atresia ani is also suspected, abdominal radiography is important to rule out the presence of megacolon. Because of communication between the urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts and the risk of ascending infection, a urinalysis and culture should be performed and appropriate antibiotics administered before surgery is undertaken.175 Affected animals should be evaluated for urinary tract infections and urolithiasis and treated appropriately.217 After a urine sample has been collected for culture, perioperative antibiotics should be administered. Before surgery, a catheter is inserted into the urethra. In patients with rectovaginal fistula, the fistula is carefully isolated through a transverse incision between the anus and vulva and transected. The anal and vaginal defects are closed with simple interrupted sutures, and the atresia ani is repaired as described previously. Alternatively, the rectum is transected cranial to the fistulous opening; the affected segment of the rectum is removed, and the cranial segment is sutured to the anus (“rectal pull-through”). In one report of two female puppies with atresia ani and rectovestibular fistula, the fistulous tract was preserved and used for the surgical reconstruction of the anal canal and anus.167 In patients diagnosed with a urethrorectal fistula, fistulectomy can be performed through a ventral pubic osteotomy, symphysiotomy, or perineal approach.215,217,300,327 Regardless of the technique used, preoperative placement of a catheter via the rectum through the fistula aids in localization and dissection.41 The fistulous tract can then be ligated and resected. Neutering is recommended because the condition may be hereditary.290 Urinary tract infections can develop secondary to rectovaginal and rectourethral fistulas. Urolithiasis has also been reported secondary to urinary tract infections and urethrorectal fistulas.192 Other postoperative complications include fecal incontinence, possibly from lack of a functional anal sphincter or direct damage to innervation of the external anal sphincter muscle during surgical dissection. Wound dehiscence secondary to tension and or fecal contamination of the surgery site has also been reported.290 Other possible complications include tenesmus, obstipation, rectal prolapse, anal stenosis, and perianal edema.35,167,239,313 Tailless breeds (e.g., Manx cats) diagnosed with rectovaginal fistula should be evaluated fully for additional neurologic abnormalities that may affect their prognosis.290 Because rectovaginal fistula is often reported in conjunction with atresia ani type II, which historically in the literature had a poor prognosis, the prognosis of patients with rectovaginal fistula is often poor. In a recent review of urethrorectal fistulas in 10 dogs and 2 cats, long-term prognosis was reported as excellent with successful excision of the fistulous tract.41 Anogenital clefts can occur in males or females. In animals with anogenital clefts, feces and urine enter a common cavity and body opening (cloaca). In females, the mucosa of the anus or rectum and vestibule are continuous along the perineal raphe. The ventral aspect of the anus is incomplete and forms the dorsal part of the cleft (Figure 94-9). Feces and urine pass easily in these patients; however, fecal incontinence, soiling of the perineum, and perineal irritation are common problems. Fecal contamination of the urinary tract can lead to ascending infections and, if not treated, pyelonephritis. Treatment of anogenital cleft in females is often satisfactory. The anus is reformed ventrally, and tissues between the anus and vulva are reconstructed. In a recent report, surgical correction of an anovulvar cleft in a dog was performed using an inverted V-shaped incision made along the mucocutaneous junction between the vulvar labia and anus. The vestibular wall was then closed with simple interrupted sutures, and subcutaneous tissues were closed with a Cushing pattern. The dog of this report was also diagnosed with a concomitant vaginal prolapse and hyperplasia.197 In males, the urethra is often incomplete ventrally, resulting in hypospadias. Because the ventral portion of the anus also fails to develop, the anal and urethral mucosa become continuous. There is usually good control of defecation and urination. Males with hypospadias can be treated by creating a urethrostomy ventrally and reconstructing the perineal tissue. A prolapse can be described as partial or complete. In a partial or anal prolapse, only anal mucosa protrudes through the anal orifice. In a complete or rectal prolapse, all layers of the rectum protrude through the anal orifice as an elongated, cylindrical mass. Prolapse usually occurs in patients secondary to tenesmus from urogenital or anorectal disease. Although no breed or sex predilections have been described, there may be an increased incidence in younger animals.32 There are many predisposing factors, including gastrointestinal parasitism; typhlitis; colitis; proctitis; tumors of the colon, rectum, or anus; rectal foreign bodies; perineal hernia; cystitis; prostatic disease; urolithiasis; and dystocia. Tenesmus and subsequent prolapse may also occur after perineal hernia repair, especially if hernias are bilateral and have large rectal sacculations or after urogenital surgery.73,127,180,181,318 Recurrent rectal prolapse in a dog secondary to colonic duplication has also been reported.156 Rectal prolapse occurred in one cat with tenesmus from extensive transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder and in another cat with intussusception secondary to an ileocecal neoplasm.13,52 It is unclear whether anatomic or functional abnormalities in some individual animals may predispose them to prolapse development.186,202 To help distinguish rectal prolapse from a prolapsed intussusception of the intestine or colon, a well-lubricated instrument or finger is passed between the prolapse and the anus (Figure 94-10). If an intussusception is present, a blunt, lubricated probe or finger can be passed easily (5 to 7 cm) between the rectal wall and prolapsed tissue.318 With a rectal prolapse, the probe cannot be passed because the prolapsed tissue converges with the mucocutaneous junction of the anus.

Rectum, Anus, and Perineum

Anatomy

. This hydrophobic sugar may control the viscoelastic properties of the anal gland mucus, resulting in a stable mucous coat for formed feces. Additionally, the excretory duct system, with its saccular dilatations, is involved with secretion maturation and production.301

. This hydrophobic sugar may control the viscoelastic properties of the anal gland mucus, resulting in a stable mucous coat for formed feces. Additionally, the excretory duct system, with its saccular dilatations, is involved with secretion maturation and production.301

Innervation

Surgical Approaches to the Rectum

Bowel Cleansing

Antimicrobials

Ventral Approach

Dorsal Approach

Rectal Pull-Through

Lateral Approach

Aftercare

Complications

Congenital Abnormalities of the Rectum and Anus

Atresia Ani

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Complications and Prognosis

Rectovaginal and Urethrorectal Fistula

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

Treatment

Complications

Anogenital Clefts

Anal and Rectal Prolapse

Diagnosis

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Rectum, Anus, and Perineum

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue