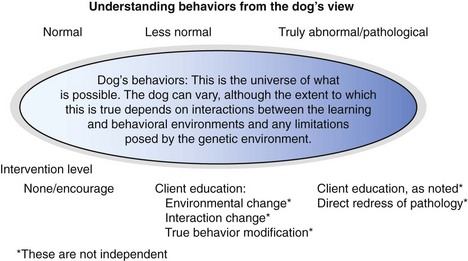

Chapter 5 Problematic behaviors can be loosely divided into two groups: (1) variants of normal behaviors that annoy clients but that respond well to understanding and management and (2) truly abnormal behaviors that are distressing to dogs and humans. Both of these sets of concerns can result in a dead, abandoned, relinquished, or euthanized dog. Where dogs fall on the continuum of “normal” to “abnormal” behaviors will determine the best types of interventions, as shown in Figure 5-1. Fig. 5-1 Conceptual diagram of the range of behaviors exhibited by dogs and which types of intervention will be needed or work best. The extent to which the dog’s behaviors are less normal and more abnormal is represented as darkening color of the oval from left to right. The intervention level required is matched to the level of pathology. • Behavioral concerns that don’t rise to the level of a diagnosis may be extreme variants of what could be normal canine behaviors or exhibition of normal canine behaviors but in contexts that may be undesirable or extreme. • Management-related behavior problems are normal behaviors in most circumstances, but some of them can progress to become part of a behavioral pathology. • jumping, scratching, bolting, and barking at the door, • grabbing people and/or other pets as they go through the door, • barking and patrolling when outside, • mouthing/grabbing/biting, and • the context in which the dog exhibits the behavior, • the intensity of the behavior, • the ability of the dog to be interrupted, and • the extent to which exhibition of the behavior affects other facets of the dog’s life in an undesirable way. • to aerosolize existing scent, • to leave a scent mark of their own, • because the objects they find are interesting or “play” back with them (e.g., tree roots), • to search for or find an animal that they hear or smell, • to extricate something to eat or on which to chew (e.g., truffles, old bones), • because they are curious and no one is paying attention to them, and • because they are hot and are trying to cool down, or because they are cold and trying to create shelter. • When dogs dig, they aerosolize scents that may have been hidden. • Most of the information dogs obtain about their physical and social environments is likely done through olfactory means. This may be why dogs sometimes scratch before they eliminate: in addition to learning about who was there before them, they contribute to the olfactory environment when they eliminate, and they wish to gauge how to spend their “olfactory currency.” • Scratching before and after elimination may convey considerable olfactory information itself about a dog’s seasonal behaviors, estrus states, social companions, and intruders. • Dogs tend to scratch more when they are not on their own property or in areas where other dogs pass frequently. • Scratching is another form of marking that has both visual and olfactory components. We know little about scents that are transferred from dogs’ paws, but we do know that this is one body region where dogs can “sweat” and that there are sebaceous glands between the dog’s foot pads. Sebaceous glands are the source of oily secretions that may be largely invisible but heavily informative to dogs because of the sensitive canine sense of smell. • Bury rawhides or other treats or toys in a bucket or tub of dirt/sand and let the dog find them. • Fill small, sturdy plastic pools with water and float food toys (at least one model of Kong floats) and/or “food-sicles” (treats frozen in broth in yogurt containers). “Food-sickles” are mentally stimulating and helpful in the hot weather and can use the same skills involved in digging. • For dogs who like to dig in really wet areas, fill a kiddie pool with water. Other objects that they find interesting can be added. • Some newer food toys have expanded on the idea of the original Buster Cube, providing both easier (Roll-A-Treat Ball) and harder puzzles. The premise for all of these items is that when the toy is batted or moved, the treats fall out. The dog is rewarded for getting the exercise of chasing the toys and for the intellectual part of figuring out how best to get the treats. • For dogs who dig to thermoregulate, provide other thermoregulation choices (e.g., pools, fans, digging pits created by filling kiddie pools with wet sand and placing them under shade trees, allow the dog in or provide a heated dog house in the winter, et cetera). Some vets have cooling/warming packs, if additional heating and cooling is needed. Many dogs dig because they are of a breed that we asked to dig. Jack Russell terriers, Glen of Imaal terriers, fox or rat terriers, et cetera, all were developed to track, chase, and kill earth-dwelling animals. For these dogs, clients may consider earthdog trials (see www.akc.org/events/earthdog for information) where the dog’s skill is directed to an appropriate venue for—digging. Following are common situations created by humans that turn into problems for the dogs. • Dogs have been selected to bark to alert humans to visitors. When people open a door, they do not ask the dog to sit and be quiet before they actually open the door to whomever is on the other side. The dog is now aroused and made more aroused by barking, and standing, at the door in way that the new person is right in front of them when the door opens. • Ask clients to acknowledge the bark, attend to what’s going on, and ask the dog to sit and be quiet, then tell the dog that he is brilliant when he sits quietly. Wait until this happens. No one must open a door immediately, and by doing so clients may further stimulate a dog who is already overwhelmed. • Quiet can be maintained for many dogs by quickly offering the dogs a toy and telling them they can get up when they “take it.” Dogs cannot bark annoyingly with their mouth full, they self-reward for being quiet, and dogs with toys are less likely to jump and instead greet everyone by carrying a toy around and wiggling. This solution is so simple that—of course—few people think of it. • When dogs start to lunge at or through doors or jump on people who are entering, their humans tend to pull the dog back by the collar. Dog push against pressure: this means that when you grab a collar, it tightens under the dog’s throat, and the dog lunges harder. Humans then tend to yell at the dog who, understandably, is now fairly confused. • Ask the dog to sit quietly, as noted, or use a physical cue to stop the dog. The client can place a hand gently against the dog’s chest so that the dog backs up. • Clients concerned about grabbing, biting, or fleeing have two other choices.

Problematic Canine Behaviors

Roles for Undesirable, Odd, and Management-Related Concerns

Management-Related Behavior Problems and Concerns That Do Not Rise to the Level of a Diagnosis

Digging

Why Do Dogs Dig?

Roles for Olfaction

How Can We Meet a Digger’s Needs?

Are Some Breeds Likely to Be Diggers?

Jumping, Scratching, Bolting, and Barking at the Door

Isolate the dog behind a baby gate elsewhere before they expect guests. The dog can be let out to join the people when the door is closed, the greetings are completed, and people are calm and sitting down.

Isolate the dog behind a baby gate elsewhere before they expect guests. The dog can be let out to join the people when the door is closed, the greetings are completed, and people are calm and sitting down.

Put a head collar on the dog when home to supervise him and allow him to drag a light lead that slips through furniture. When someone comes to the door, clients can do the aforementioned plus:

Put a head collar on the dog when home to supervise him and allow him to drag a light lead that slips through furniture. When someone comes to the door, clients can do the aforementioned plus:

Ask the dog to sit and ensure that he does so by gently pulling up on the lead.

Ask the dog to sit and ensure that he does so by gently pulling up on the lead.

Close the dog’s mouth by gently pulling forward on the head collar. The dog can then have a toy. If he doesn’t like toys, he can have a treat for being quiet. The dog must have a reward once he is calm and quiet; praise is not enough.

Close the dog’s mouth by gently pulling forward on the head collar. The dog can then have a toy. If he doesn’t like toys, he can have a treat for being quiet. The dog must have a reward once he is calm and quiet; praise is not enough.

If clients believe that the dog might snap at or bite the person at the door, they should not have the dog at the door. The dog should be behind a baby gate, in a crate out of the way, or locked behind another door. Visitors need to know that the dog might snap or bite and not be able to interact with the dog. Some dogs are too reactive to humanely introduce to visitors, even when on leads and head collars. These dogs are best protected from people, which, in turn, protects the people, too.

If clients believe that the dog might snap at or bite the person at the door, they should not have the dog at the door. The dog should be behind a baby gate, in a crate out of the way, or locked behind another door. Visitors need to know that the dog might snap or bite and not be able to interact with the dog. Some dogs are too reactive to humanely introduce to visitors, even when on leads and head collars. These dogs are best protected from people, which, in turn, protects the people, too.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree