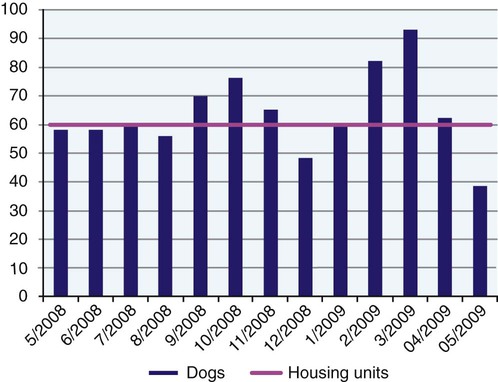

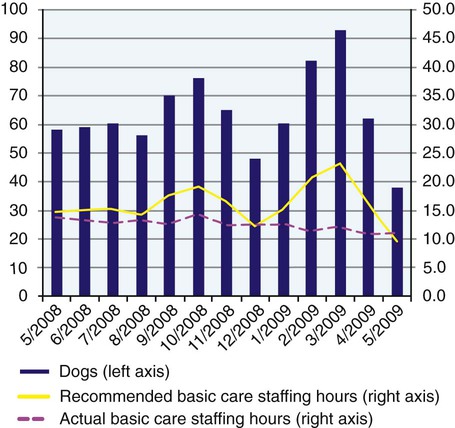

Regardless of their intended purpose, all canine populations share general features, including close proximity of residents, some means of confinement, systems for sanitation and husbandry, and some means to deliver preventative and individual animal health care. Each facility, however, possesses unique features that influence outbreaks of infectious diseases. Important factors include geographic distribution of disease and the characteristics of both the facility and the dog population. For example, canine parvovirus (CPV) can persist long-term in some environments if not effectively destroyed or removed. However, vaccinated adult dogs can show minimal evidence of exposure, whereas populations that include naïve puppies are likely to experience greater incidence of clinical CPV infection in such an environment. Clinical diseases caused by more labile agents are influenced by interactions between environmental stressors and the natural biology of the agents. One important example is canine infectious respiratory disease complex, which may be seasonal or endemic in crowded boarding kennels or shelters (see Chapter 6).3 Shelters offer unique challenges because transient dogs carry pathogens common to the larger community and can appear clinically healthy even while shedding pathogens. Regardless of the type of facility, strong preventative health care is necessary. A comprehensive population infection control program requires planning and can be a significant expenditure. Veterinary professionals are essential in the assessment of risk factors, in the development of policies and procedures, and in the assessment of effectiveness of these measures.22 Practicing veterinarians in the community are essential as well for assessment of infection control, because healthy animals, once released into the larger community (adopted, fostered, purchased), can develop disease. In all canine population environments, planned preventative care management is far more efficient and cost effective compared with purely therapeutic or reactive management to infection outbreaks. In addition, thorough educating of owners, managers, and staff is critical to successful implementation of a plan.32 Zoonoses are of concern in all dog populations, particularly those with a high level of public interaction such as dogs in shelters and pet stores. Specific strategies, including training and availability of personal protective equipment, should be in place to ensure that staff and public health risks are minimized.9 Periodic introduction of disease into canine populations is nearly inevitable, especially in transient populations. The likelihood that disease introduction will lead to transmission within a given population depends on the virulence of the organism, the method of spread, and environmental factors that influence level of exposure. In populations where dogs are singly housed, direct transmission is of minimal importance. If dogs have direct contact through open cage panels or are allowed to intermingle in play groups or common areas during cleaning, the direct route of transmission becomes more significant. The most common method of spread among singly housed dogs is likely to be transmission via contaminated fomites, such as hands, clothing and footwear, equipment, or surfaces. Aerosol transmission is a concern for canine respiratory pathogens such as canine distemper virus (CDV) and canine influenza virus, which can spread over distances up to 50 feet.2,18,18 Pathogens such as CPV that are not normally airborne can nonetheless be spread by power sprayers or via dust spread by high-power fans. Vector-borne transmission can be an issue in populations where external parasites or biting insects are not controlled.36,51 To avoid overcrowding, the appropriate capacity of the facility must first be determined. Maximum capacity should be calculated and not exceeded. Ideally, no more than 80% of capacity should be the norm, to allow flexibility in managing dogs with special needs and to prepare for unexpected influxes. Capacity depends on the number of appropriate housing units and available staff time and can vary by subpopulations. For example, capacity for puppies cannot be the same as that for adult dogs, because special housing is required to prevent exposure of puppies to infectious disease. Appropriate housing units are described later in General Considerations for Kennel Design and Layout as it Relates to Population Health. Required staff time per dog will vary depending on the daily care requirements of the dogs, the type of housing, and the method of cleaning used. According to the National Animal Control Association,38 15 minutes per dog is required for minimal daily care and cleaning. More time will be required to husband animals if the facility design prohibits efficient cleaning. It is more labor intensive if dogs must be removed from their kennels to a holding area that must be disinfected between uses. A better design would be to house dogs in a double-sided run where the dog can be moved to one side while the other side is being cleaned. Basic care activities should be performed and a minimum time requirement per dog calculated. Additional time must also be allocated for medical care, socialization, and other special needs depending on the type of facility. In order to calculate staff capacity of an organization, available total staff time for care is divided by the number of minutes required per dog. For example, a facility that has one staff member providing 8 hours of daily care, in which dogs require 30 minutes of care each, has a staff capacity of 16 dogs. Documenting facility and staff capacities compared to actual average daily animal census on a monthly basis can be helpful for organizations experiencing a great deal of variation in daily population over the course of a year, such as shelters and some boarding facilities (Figs. 96-1 and 96-2). The average daily population for the month is calculated by summing the daily population for each month and dividing by the number of days in that month, or can sometimes be estimated by determining the population for a typical day in each month. This will be accurate for facilities that do not experience significant fluctuations within a single month. The building layout and defined zones will vary based on the mission and function of each facility. Specific zones should be separated and designated by signage to minimize transmission of disease. Some units will have a public zone (e.g., veterinary hospitals, boarding and grooming facilities, shelters) that can include an entry area, housing areas, and activity areas. All units should have a restricted zone that includes rooms where animals are received, are held once entering the facility, and are examined for health assessment and treatment. Some facilities, such as breeding facilities and some shelters, need a physically isolated intake area to hold animals for observation and diagnostic testing before introducing them to the population. In addition, separate quarantine or isolation rooms are needed for dogs exhibiting signs of disease. Areas for pregnant bitches, nursing puppies, and weaned puppies should be located away from the general population. Additional detail on segregation is provided later in this chapter, and further information on facility design is available (Box 96-1).52 The minimum size of enclosures depends on size, breed, length of confinement, and individual circumstances, and minimum recommendations have been published by the Humane Society of the United States,19 the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Department of Agriculture of the United States,1 and the National Research Council.39 See Box 96-1 for Internet sources for these documents and organizations concerned with animal welfare.1 Barring medical conditions requiring close confinement, enclosures must be of sufficient size to allow dogs to assume all normal postures without touching the sides of the enclosure and to urinate and defecate away from feeding and sleeping areas; must accommodate bedding; and must allow for expression of a range of normal behaviors. Size and quality of housing will need to be greater for dogs staying in confinement for longer time periods (more than 2 weeks) and for whom no other avenue for exercise, play, and socialization is routinely provided. In production units or shelters, areas for pregnant bitches, nursing bitches, and litters are needed. Space should be adequate for the bitch to separate herself from the litter. Enclosures should have solid barriers between adjacent enclosures to minimize transmission of pathogens. Double-sided kennels separated by a guillotine door facilitate cleaning, provide separation of areas for feeding/resting versus elimination, facilitate cleaning of enclosures without exposing animals to water or disinfectants, and allow care of even aggressive dogs with minimal risk to staff (Fig. 96-3). This kennel design is generally preferred to single runs, particularly for newly admitted dogs, aggressive dogs, and dogs suffering from infectious disease. Puppies should always be housed in easily sanitized double-sided cages or runs that permit easy and efficient cleaning and care. Doors on kennels or runs should be secure.

Prevention and Management of Infection in Canine Populations

General Characteristics of Canine Populations

Disease Transmission

Defining Capacity/Managing Population Density

General Considerations for Kennel Design and Layout as It Relates to Population Health

Kennel Type and Size

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine