Preprocedure Considerations

Preprocedure Considerations

Site Selection and Facility Requirements

A small animal surgery table may be used for alpacas and smaller llamas. A foal or small ruminant surgery table or a heavy-duty gurney will be required for larger llamas. A foam pad should be used to cushion the table surface. A shallow trough shaped pad (4-inch base thickness) makes dorsal recumbency easier to maintain and, in many cases, may be used for patients in lateral recumbency. A large animal surgery table is required for larger camels. Llamas and alpacas are typically transferred from the floor to the surgery surface and back manually. It is important to ensure that adequate personnel are available for intended transfers. A 1- to 2-ton overhead hoist may be used to move larger camelid patients into a better working position on the floor (preferably on a foam pad) or onto a surgery table. If the ceiling will not support an overhead mounted hoist without extensive modification, a lateral pull using a wall-mounted winch system may be used to reposition larger patients. Multiple mounting points and a portable winch allow patients to be moved to various areas of the operating theater. Two sets of hobbles connected by rings to the hook of the hoist or winch are used to move the patient. Hobbles are traditionally placed on the pastern but may be positioned above the fetlock, if required, to ensure a secure grip on the legs. Hobbles may be fashioned by splicing loops at each end of short segments of 1-inch cotton rope. The body of the rope segment is then fed through each loop to create the sliding component of the hobble. The distance between the loops needs to be sufficient to make placing and removing the hobbles easy, but excessive length reduces the height to which the patient can be lifted using an overhead hoist. Canvas strap hobbles (Shanks Veterinary Equipment, Inc., Milledgeville, IL) are available commercially. The wider, stiffer, canvas strap hobbles require more attention to attain a snug and secure fit. Good facility design makes managing larger patients safer and requires fewer personnel.1

Patient Positioning

Camelids continue to salivate when sedated or anesthetized. The degree of protective laryngeal and eye reflexes retained will depend on the chemical restraint or anesthesia technique used and the drug doses selected. Camelids tend to lie down with heavier levels of sedation. Camelid patients that remain standing or are able to maintain sternal recumbency when chemically restrained typically clear saliva effectively. Patients in lateral or dorsal recumbency should be positioned such that saliva runs out of the mouth rather than pooling back near the larynx. In patients in lateral recumbency, this may be accomplished simply by placing a pad under the head–neck junction such that the opening of the mouth is below the level of the larynx (Figure 44-1). A mild downward tilt is generally all that is needed, as use of an overly large pad may impair venous return from the head, resulting in edema formation.

Protecting the airway becomes much more challenging when the patient is placed in dorsal recumbency. Camelid patients placed in dorsal recumbency will typically be under the influence of a potent chemical restraint protocol or anesthetized. The body should be elevated to produce a slightly dependent head position. The neck should be gently twisted so that the head rests laterally on the surgery table or floor (Figure 44-2). A shallow trough shaped pad (4-inch base thickness) provides the proper height and makes dorsal recumbency easier to maintain. This positioning places the mouth opening below the level of the larynx to facilitate saliva egress. The long neck of camelids makes this fairly easy to accomplish. A small pad placed under the head–neck junction may be needed to achieve the proper degree of head tilt. The head must be supported, rather the left hanging, to prevent excessive tension on vital neck structures and reduce the extent of edema formation. Placing the head in a dependent position increases hydrostatic pressures within the blood vessels of the head, which, over time, results in edema formation of the nasal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal tissues, as well as the eyelids. Minimizing the degree of dependence of the head relative to the body to only what is necessary to provide saliva egress may help to reduce the degree of edema formation.

Endotracheal Intubation

The camelid patient should be intubated when the head cannot be positioned to facilitate salvia egress or the procedure could result in blood or other material entering the airway. Intubation is also required to deliver inhalant anesthetics (saliva production precludes safe mask delivery of oxygen or inhalants).

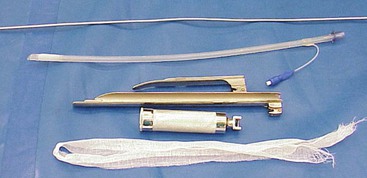

Alpacas and llamas are intubated by direct visualization, as in dogs and cats. Because of the small mouth opening and deep oral cavity in camelids, proper alignment is important to visualize the larynx (Figure 44-3). This is similar to looking through a long, narrow tube. A laryngoscope with an extra-long blade aids visualization of the larynx by allowing greater control of the base of the tongue (Wisconsin 11-inch, 14-inch, and 18-inch laryngoscope blades; Anesthesia Medical Specialties, Beaumont, CA) (Figure 44-4). The ET tube must be long enough to place its inflatable cuff below the level of the larynx in the trachea. Oral cavity depth of larger alpacas and llamas typically requires the use of longer 5- to 14-mm silicone “foal” ET tubes (Bivona Aire-Cuf Standard Silicone Endotracheal Tubes with Murphy Eye and Connector, Smiths Medicals). A selection of ET tube diameters should be available to ensure proper fit.

Figure 44-4 One eighth of an inch aluminum stylet, Bivona Aire-Cuf silicone endotracheal tube, Miller 4 laryngoscope blade, Wisconsin 11-ich laryngoscope blade, laryngoscope handle, and gauze tie.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree