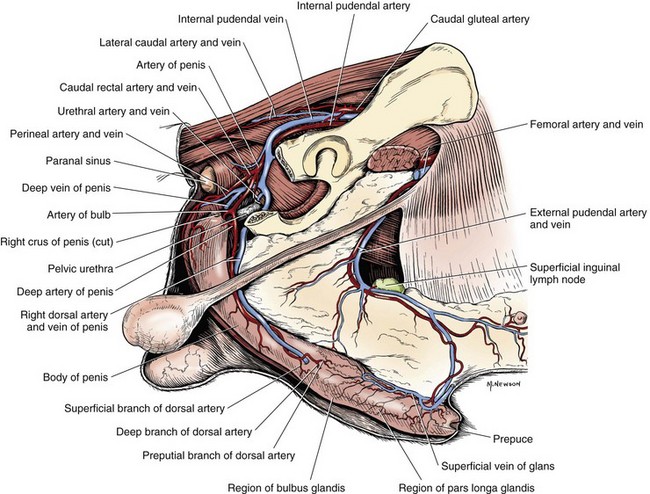

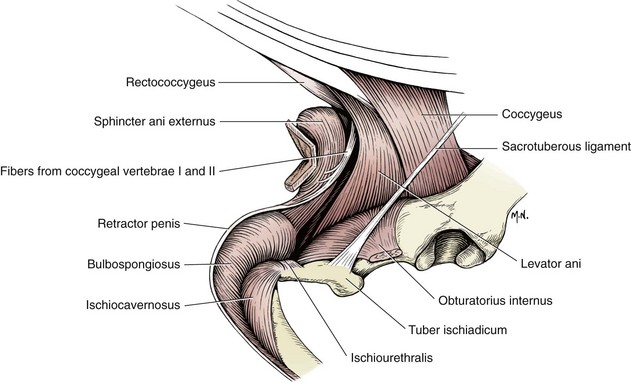

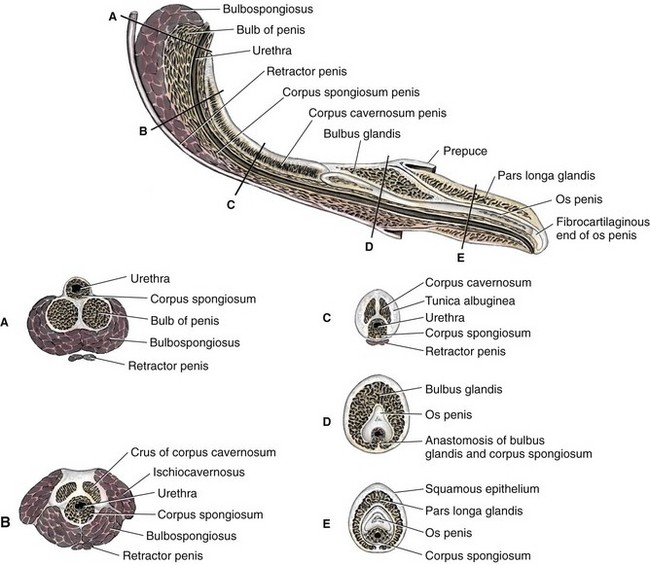

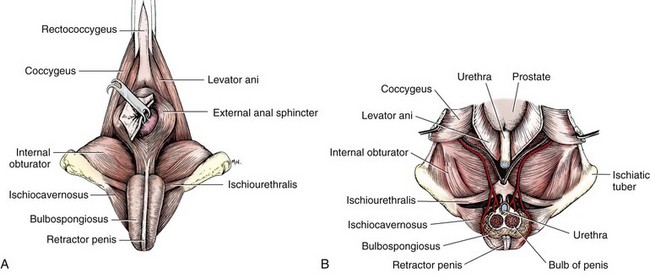

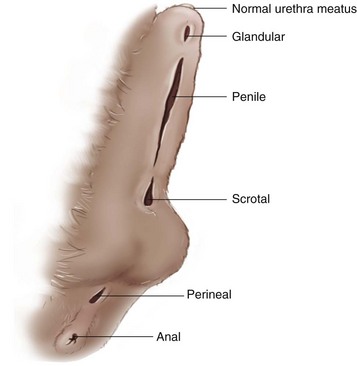

Chapter 112 The penis is composed of three principal divisions: the root, body, and distal portion (Figure 112-1). The root (Figure 112-2) is attached to the tuber ischii by the left and right crura. Each crus is composed of the proximal part of the corpus cavernosum and the ischiocavernosus muscle covering it (Figures 112-3 and 112-4).13 The corpus spongiosum contains the penile urethra and is situated ventrally within the penile root. The bulb of the penis is a bilobed expansion of the corpus spongiosum located between the crura at the ischial arch. The body of the penis begins at the blending of the crura, extends just beyond the proximal end of the os penis, and is directly continuous with the root. The corpora cavernosum and spongiosum constitute the main substance of the penile body. The distal portion, or glans, in dogs is subdivided into a smaller proximal portion, the bulbus glandis, and a larger distal portion, the pars longa glandis. The distal half of the bulbus glandis is overlapped by the caudal third of the pars longa glandis. There are four paired extrinsic penile muscles in dogs: the retractor penis, ischiocavernosus, bulbospongiosus, and ischiourethralis muscles (see Figures 112-2 and 112-4). The retractor penis muscles are composed principally of smooth muscle fibers. They arise from the first two caudal vertebrae, blend with the external anal sphincter, run along the ventral surface of the penis, and insert on the penis at the level of the preputial fornix. The ischiocavernosus muscles originate from the ischial tuberosity and insert on the corpus cavernosum. The bulbospongiosus muscles arise from the external anal sphincter, cover the superficial surface of the bulb of the penis, and fuse with the retractor penis muscles at the proximal third of the penile body. The ischiourethralis muscles originate from the dorsal aspect of the ischial tuberosity and insert into a fibrous ring at the urethral bulb. The primary blood supply to the penis is from three branches of the artery of the penis, the continuation of the internal pudendal artery (see Figure 112-1).13 All three branches—the artery of the bulb, deep artery of the penis, and dorsal artery of the penis—anastomose with one another. The paired arteries of the bulb supply the corpus spongiosum, penile urethra, and pars longa glandis. The deep artery of the penis passes through the tunica albuginea to enter the corpus cavernosum. The dorsal artery of the penis, the continuation of the main trunk, is located on the dorsolateral surface of the os penis beneath the erectile tissue. This branch supplies the corpus spongiosum, bulbus glandis, and pars longa glandis. The feline penis is shorter and directed caudally. Its urethral surface faces caudodorsally, and its dorsum faces cranioventrally.25 Similar to that of dogs, the penis in cats consists of a proximal cavernous and a distal osseous part. The free part of the penis of a sexually mature cat is studded with small cornified papillae, called penile spines.25 Penile spines appear in kittens as early as 12 weeks of age and are usually obvious by 6 or 7 months of age. They regress within 6 weeks after castration; persistence is an indication of increased serum testosterone level, usually because of the presence of a testicle. In dogs, the prepuce is a complete tubular sheath that covers the pars longa glandis and part of the bulbus glandis in the nonerect penis. It is firmly attached and continuous with the skin of the ventral abdominal wall.13 The prepuce is composed of two layers of integument dorsally and three layers ventrally, laterally, and on the cranial aspects of its dorsal surface. The outer layer is skin, and the inner layers, parietal and visceral, are made up of thin, stratified squamous epithelium. The parietal layer is a continuation of the outer skin layer onto the wall of the preputial cavity. It extends to the fornix, which is located at the level of the middle of the bulbus glandis. The parietal layer is stippled with many lymph nodules and nodes, particularly along the fornix. The visceral, or inner, layer extends from the preputial fornix to the external urethral orifice. It is continuous with the cavernous urethra. Paired preputial muscles, which extend from the xiphoid cartilage to the dorsal wall of the prepuce, are derived from the cutaneous trunci muscle.13 Erection is essential for the penis to function during copulation in all species except dogs.30 The canine os penis facilitates vaginal entry without full erection and influences the urethral orifice orientation during intromission.30 The basis for penile erection is a profound increase in blood supply via the internal pudendal artery secondary to parasympathetic stimulation.10 Erection is accomplished by synergy of two mechanisms. First, engorgement of the cavernous bodies of the penis occurs through expansion of the arteries and contraction of the veins.9 Second, the dorsal penile vein is compressed against the ischial arch by contraction of the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles.30 The extent to which cavernous spaces expand during erection depends on the development and composition of the connective tissue tunics of the penis. Erection involves primarily the glans penis in dogs and cats.30 Enlargement of the bulbus glandis in dogs is an important part of the “tie” that occurs during copulation. The cornified spines of the penis in cats are proposed to stimulate ovulation. At birth, preputial and penile epithelial surfaces adhere. Separation of the prepuce from the penis is under androgenic influence and usually occurs at puberty. The preputial muscles keep the prepuce over the penis. They are classified as “slow” muscles and are similar to the cremaster muscle in their contraction properties.35 Hypospadias is the most common developmental anomaly of the male external genitalia (Figure 112-5) and is encountered most frequently in Boston terriers.19 Clinical signs may be absent if the prepuce is normal and the external urethral orifice is near the end of the penis. Occasionally, the skin and hair around the urethral orifice are urine soaked and irritated.16 Hypospadias results from failure of fusion of the urogenital folds and incomplete formation of the penile urethra.1 The external urethral orifice can occur anywhere on the ventral aspect of the penis from the normal opening to the perineal region, with glandular, penile, scrotal, and perineal hypospadias described (Figure 112-6).1 Hypospadias is usually associated with failure of fusion of the prepuce and underdevelopment of the penis (see Preputial Hypoplasia). The diagnosis of hypospadias is made by close inspection of the penis. Surgical reconstruction of the penile defect is not usually attempted in dogs because the urethra cranial to the abnormal orifice is deficient.19 Excision of preputial and penile remnants, bilateral orchidectomy, and enlargement or maintenance of the urethral orifice in the scrotal or perineal region (see Urethrostomy in Chapter 117) may be indicated in severe cases.16 The os penis may rarely develop with a pronounced curvature.19 Because of the curvature, the dog may not be able to retract the distal penis into the prepuce. The exposed part becomes dry and fissured, resulting in infection and necrosis.4,19 Treatment depends on condition of the penis. Local treatment of the exposed penis is usually not effective without treatment of the bony curvature. Straightening the os penis by fracture may be possible if infection and necrosis are not present.4 Partial penile amputation may be necessary in severe cases (see Penile Strangulation). Fracture of the os penis occurs rarely. Clinical signs depend on the extent of soft tissue damage and fracture displacement, with dysuria and hematuria being common. Crepitus is apparent, and urethral obstruction may occur. Urethral obstruction may also be observed in association with callus formation.36 Fractures are usually transverse with limited soft tissue damage, although they may be comminuted.19 Radiography reveals the extent of damage to the os penis. Conservative management of this fracture is often successful.19,24,36 Minimally displaced simple fractures do not require immobilization.19 More severe fractures can be adequately immobilized with a urethral catheter. The catheter end should be positioned beyond the fracture site and attached to a closed collection system for 7 days. If a catheter cannot be passed because of urethral damage or if the fracture is unstable with urethral catheterization, open reduction and fixation with a finger plate has been successful.36 Fractures accompanied by severe penile trauma may necessitate partial penile amputation (see Penile Strangulation). If urethral obstruction occurs because of callus formation, a prescrotal or scrotal urethrostomy can be performed (see Chapter 117). Hemorrhage, frequently intermittent but often profuse, is the most common clinical sign of penile wounds. Hemorrhage is associated with penile erection, which in turn is caused by irritation from the injury. Rupture of the penile urethra is usually accompanied by fluctuant subcutaneous swelling associated with urine extravasation. Because of its exposed location, the penis is relatively accessible to injury. Penile wounds may occur during mating, dog fights, and fence jumping or from automobile accidents or gunshot.14,19,24 Penile lacerations and gunshot wounds may involve the urethra. Severe penile trauma may produce a fracture of the os penis (see Os Penis Fracture). Minor injuries to the penis can be cleaned and treated with a topical antimicrobial ointment. These wounds are usually allowed to heal by second intention. If significant hemorrhage occurs, the wound should be debrided as needed and sutured. Arterial bleeding is controlled by ligation and cavernous bleeding by suturing the tunica albuginea with fine absorbable material. Penile mucosa is closed with fine absorbable material. Parenteral and local antimicrobials are administered postoperatively, and penile erection is prevented by sedating the animal.19 Wounds of the penile urethra are usually treated by catheterization, provided the urethra has not been transected. A transected urethra should be sutured with fine absorbable material and then catheterized (see Chapter 117). Catheters should remain in place, using a closed collection system, for 5 to 7 days with minor penile urethral tears and up to 10 days after urethral anastomosis. Severe wounds may require partial penile amputation (see “Penile Strangulation”) and a scrotal urethrostomy (see Chapter 117). The prognosis for penile wounds is generally good, provided that the urethra has not been transected. Urethral stricture is possible, especially after transection and anastomosis.

Penis and Prepuce

Anatomy

Prepuce

Physiology

Prepuce

Specific Disorders

Os Penis Deformity

Os Penis Fracture

Penile Wounds

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Penis and Prepuce

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue