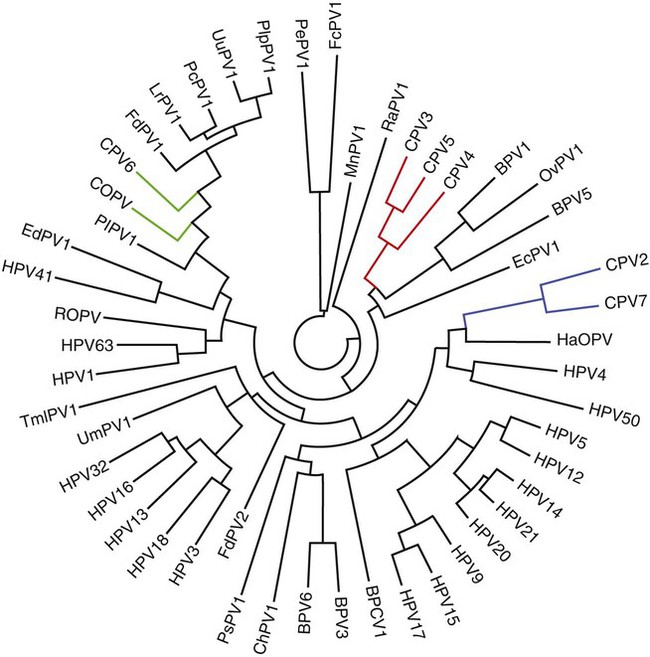

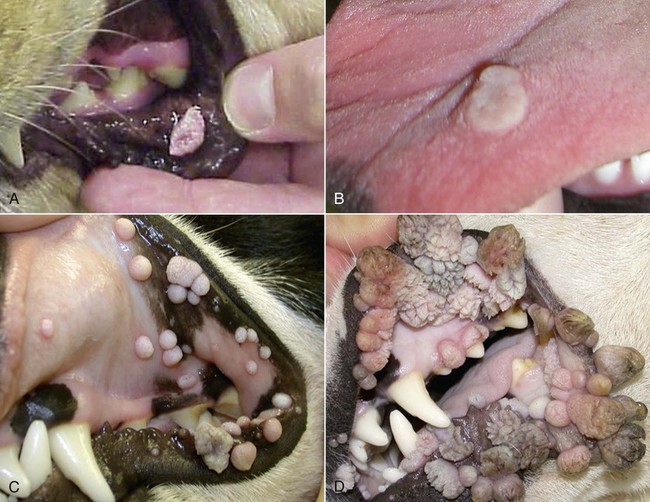

Members of the genus Papillomavirus (PV) are small (30 to 60 nm) nonenveloped viruses with icosahedral symmetry and double-stranded circular DNA genome. They are categorized, along with polyomaviruses, in the Papovaviridae family. They lack a lipid envelope, which may explain their resistance in the environment.42 PVs are widespread in nature and infect many species of mammals and birds.85 They are very strictly host-specific, and their replication is tightly associated to host-cell differentiation.28 For example, inoculation of canine oral papillomavirus (COPV) into kittens, mice, rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates has failed to produce papillomas. Cross-species infection of horses by bovine PVs type 1 and type 2 has, however, been reported.18 Animal PVs cause benign cutaneous and mucosal proliferations that are usually self-limiting and only rarely progress to malignant tumors.1,89 Human PVs (HPVs), on the other hand, induce a wide range of infection, some of them being commensal, whereas others cause neoplastic transformation, especially on the mucous membranes.2,3,108,109 More than 100 HPVs have been isolated, cloned, and sequenced completely and many more partially.27 They have been grouped into the genera α-, β-, γ-, δ- and µ-PV. Not only HPVs but also a growing number of animal PVs have been detected in lesional and in healthy skin of mammals, birds, and even reptiles. It can be anticipated that each animal species as well as humans may harbor carry a large set of PV types. Descriptions of seven virus genomes obtained from dogs and two obtained from cats have been published to date.* Additionally, smaller unique genetic sequences have been uncovered in other feline and canine samples, which suggest that other PVs exist in these species.63,67,67 Munday and co-workers detected two to three different PV sequences in the same feline sample, which mirrors the situation in humans, where multiple infecting PVs are often identified.61a,64 Classification of PV is usually based on L1 gene sequences, but this classification only partially correlates with clinical features such as oncogenic potential and localization of induced lesions.27 Data from the phylogenetic tree presented in Fig. 18-1 supports the contention that similarity in genetic makeup does not correlate with that of clinical findings. CdPV3 (host: Canis lupus familiaris PV) and CdPV7, for example, have been discovered in in situ carcinoma lesions but are phylogenetically distinct. FdPV1 and FdPV2 (host: Felis catus) do not belong to the same PV genus but have both been extracted from Bowenoid in situ carcinoma (BISC). Inverted papillomas have been described in association with COPV, CdPV6 but also CdPV2.48 Feline sarcoids from North America and New Zealand both contained a genetically identical papillomavirus, FeSarPV, that was not detected in nonsarcoid samples, including those from cats with other tumors and clinically healthy skin and oral mucosal specimens.62a,63a HPV entry within the squamous epithelium may induce a latent infection in which there is no clinical and microscopic evidence of disease, a subclinical infection that reveals microscopic lesions in the absence of grossly visible lesions, or an overt clinical disease.41 For successful initiation of productive infection, infectious particles must penetrate cells in the basal layer, which requires, in most cases, a break in the epithelium.28 In all cases, however, initial infection is followed by a viral latency period, during which viral genome undergoes replication as autonomous extrachromosomal elements.4 Typically, following differentiation of the basal cells into maturing epithelium, expression of capsid genes is induced to produce mature viral and corresponding grossly visible lesions. However, equine and feline sarcoids remain latent infections, that is, they are not associated with production of new viral particles. The prevalence of subclinical PV infections in dogs and cats is uncertain. However, in one single serologic study,49 7.4% to 50.2% of healthy dogs had antibodies against COPV and/or CdPV3. The range reflected the geographic region surveyed and the cutoff value employed in this determination. For overt clinical infection, the PV must overcome the host’s immune response to replicate, so the significance of PV infection may be greater in immunocompromised patients.18,45 Inherent immunity is implied by the apparent breed predisposition for the development of one specific PV-associated canine condition, namely pigmented plaques, which has been established for pugs.13,66,66 Similarly, adult cocker spaniels and Kerry blue terriers may be prone to skin papillomas.78,80 Improved detection techniques have permitted not only the characterization of novel carnivore PVs but also the detection of PV nucleic acids in a wide range of skin lesion such as in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). However, because the most sophisticated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are now able to detect as few as one PV genome copy among 100 keratinocytes, one must interpret very carefully any positive results obtained with such assays.73 In fact, the ability of so few viruses to have any influence on the development of neoplasia in the harboring tissue is very doubtful. For example, using PCR detection, FdPV2 was found in skin of 52% of clinically healthy cats, regardless of their age, sex or being infected with FIV.64a In contrast, positive results obtained with older techniques such as immunohistochemistry (IHC) are far more meaningful. Such assays are positive only if an appreciable amount of viral capsid proteins are present in the sample. Hence, the IHC test, when results are positive, demonstrates not only the presence of the virus but also its active replication, which is more likely to be clinically significant. Positive IHC results have been demonstrated only in canine warts, canine pigmented plaques, viral plaques, and feline BISC.105 Additionally, PV DNA has been shown to be present in most (17 of 20) feline skin invasive SCCs and rare (1 of 20) oral invasive SCCs.62,63 The life cycle of the PV is usually confined to the epidermis and epithelium and closely associated with the differentiating epithelial cell.78 Early HPV genes (E genes) are expressed at the basal and suprabasal level of the epidermis, whereas late genes (L1 and L2) are expressed in the spinous and granular cell layers.28 Virion assembly finally occurs in the upper stratum granulosum and stratum corneum. After infection, hyperplasia in the stratum spinosum occurs, and proliferation of the epithelium (acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, with wart formation) becomes clinically evident 4 to 6 weeks postinoculation.70 Intranuclear inclusions (aggregation of viral particles) are detected only in the upper epidermis, whereas other cytopathic effects (intracytoplasmic pseudoinclusions, koilocytosis, clumped keratohyalin granules) are usually present in the mid and upper epidermis.36 Spontaneous wart regression is the usual course and occurs after 6 to 8 weeks.70 Regressing warts are usually observed in younger dogs, whereas persistent PV infections have been reported mainly in adult dogs. As well, lesions in 6- to 7-month-old kittens have been reported, but most cases were in cats 6 to 13 years of age.30,93 Immunodeficiency is associated not only with increased chance of clinical manifestation but also with persistent infection and neoplastic transformation.19,29,30,32,70 The presence of neutralizing antibodies in dogs after wart regression has long been recognized.21,22 These antibodies prevent PV reinfection in most dogs but do not induce regression of established tumors. This suggests that tumors regression is associated with a cell-mediated response. This hypothesis is supported by the presence of lymphocytic infiltrates in most regressing warts in dogs and in many other species.70 The outcome of PV infection depends on the intrinsic pathogenicity of the PV strain and host immunity and genetic background. In fact, linking causal association between the mere presence of PV infection in carnivores and resulting neoplastic transformation is still problematic. Although epidemiologic evidence suggests such an association, at least in cats (see earlier discussion), direct causality has never been confirmed in vitro in cats or dogs. CdPV3, for example, has been recovered in a European Rhodesian ridgeback with multiple in situ and invasive skin SCCs, but antibodies against the same virus have been detected in up to one third of healthy dogs in South Africa.49 In addition, infections with closely related viruses seem to have different outcomes. Carnivore PV possess oncogenes (E6, E7, E5 for some of them), but eventual expression of these genes probably depends on interactions with the host immune response. Goldschmidt and co-workers, for example, have isolated CdPV2 from inverted papillomas and invasive SCC of immunocompromised beagles.32 This does not mean that the same virus induces skin cancer in an immunocompetent host. Typically warts occur in younger dogs (Fig. 18-2, Web Fig. 18-1). The oral mucosa is mainly affected by this COPV-associated condition. Eyelids, lips, esophagus, and haired skin may also be secondarily affected (Web Fig. 18-2). Regression usually occurs within a few weeks. Adult dogs’ skin may also be affected by other forms of papillomatosis, especially the footpads and the perigenital skin (Fig. 18-3, Web Figs. 18-3 and 18-4). Kerry blue terriers and cocker spaniels may be overrepresented in this group of patients. Multiple warts developed postoperatively on the skin of an adult dog at the site of preparation for a laparotomy.61b Outbreaks of oral papillomatosis in large groups of kenneled dogs have occurred.105b Wart-like lesions on the footpads of greyhounds do not appear to be associated with papillomavirus as do similar lesions of other dog breeds.4a The canine counterpart to the feline plaque (see Cats, later) is called canine pigmented plaques and consists of small to medium-size, dark plaque-like, and hyperkeratotic lesions occurring usually on the limbs or abdomen (Fig. 18-4). They were initially referred to as lentiginosis profusa, and pugs are considered to be predisposed to the formation of these plaques.13 The viral origin was subsequently demonstrated by Nagata.65 The same authors have suggested that these lesions in carnivores could be the counterpart of human epidermodysplasia verruciformis. However, some major differences between these conditions exist and any premature comparison should consequently avoided.36 Tobler and co-workers demonstrated that four affected pugs were infected by the same PV, namely CdPV4.101 Other canine PVs, namely CdPV3, CPV5, and CdPV7, have been associated with the same clinical presentation in other breeds.47,100 These lesions sometimes develop into in situ or invasive SCC (Fig. 18-5).35,47,47 Inverted papillomas are warts that develop downward into the skin. This development results in raised and smooth nodules, usually 1 to 2 cm in diameter, with a central pore filled with keratin (Fig. 18-6). They usually occur on the abdomen and may be solitary or multiple. Spontaneous regression is uncommon, and surgery is the treatment of choice. This classical type of inverted papillomas was first described by Campbell and co-workers.16 Three other types have been described, and each may be associated with one specific PV.32,48,52,80 The macroscopic appearance of classical feline PV-induced lesions, referred to as viral plaques, is not typical of papillomas seen in other domestic animals.19,29,30,93 Although the surface of the lesions is verrucous, they appear as slightly raised plaques rather than warts (Fig. 18-7, Web Figs 18-5 and 18-6). The plaques are several millimeters in diameter; elongated lesions can sometimes be noticed. Plaques can be white or pigmented and scaly and greasy to the touch. These lesions are located on the head, neck, dorsal part of the thorax, and abdomen. They do not seem to regress spontaneously. Viral plaques sometimes occur with lesions of BISC on the same feline patient (Fig. 18-8), which supports the hypothesis that BISC arises from viral plaques.105

Papillomavirus Infections

Etiology

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Clinical Findings

Dogs

Cats

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Papillomavirus Infections