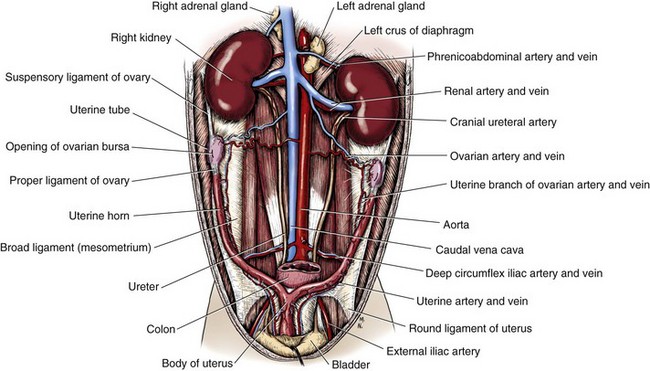

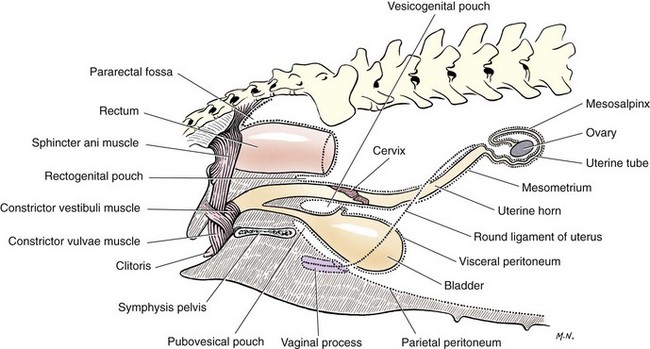

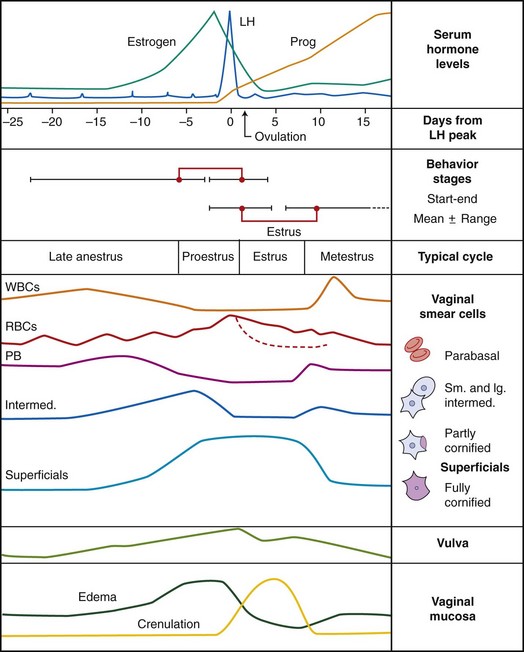

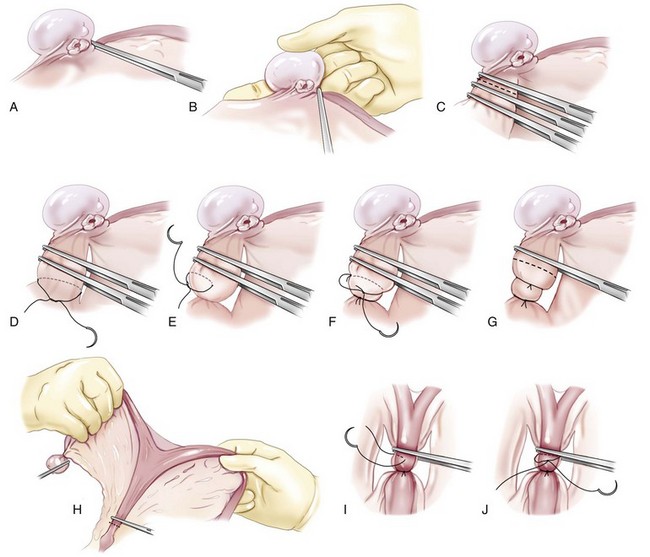

Chapter 109 In dogs and cats, the ovaries are located caudal to the kidneys (Figure 109-1). The average size of an ovary in an 11-kg dog is 15 mm long, 7 mm wide, and 5 mm thick.99 Cat ovaries are mobile, oval, and 8 to 9 mm long.232 Ovaries are smooth in appearance before estrus; in multiparous bitches, they are rough and nodular. Occasionally, the left ovary is larger than the right. The central ovarian medulla contains blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves, smooth muscle fibers, and connective tissue. In the hilar region are vestigial structures known as rete ovarii, which are small masses of blind tubules or solid cords of the same embryologic origin as rete testis in males. The cortex, located peripherally in the ovary, consists of a connective tissue stroma containing a larger number of follicles. Along the outer ovarian surface, connective tissue condenses to form a capsule, or tunica albuginea, that is covered by peritoneum. A double fold of peritoneum forms the ovarian bursa, a pouch that encloses the ovary and has a slitlike opening medially.99,129 This bursal opening is bordered by fimbriae of the infundibulum, which swell and block the opening during ovulation.99 In dogs, fat is deposited within the bursa, often obscuring the ovary. In cats, there is little fat in the bursa, which covers only the lateral aspect of the ovary.90,232 The cranial portion of the broad ligament, or mesovarium, attaches the ovary to the body wall dorsolaterally and contains the utero-ovarian vessels. The mesovarium is formed by a double fold of peritoneum. Cranially, it encloses the suspensory ligament, which attaches to the last rib. Caudally, the suspensory ligament is continued by the proper ligament, which attaches to the cranial end of each uterine horn. The proper ligament, in turn, is continuous with the round ligament of the uterus. Mesovarium is continuous with mesometrium; together, they comprise the broad ligaments and attach the uterus and ovaries to the dorsolateral body and pelvic walls. From the lateral surface of the broad ligament arises a peritoneal fold that encloses the round ligament as it passes through the inguinal canal into the subcutaneous region of the vulva. This peritoneal outpouching is known as the vaginal process (Figure 109-2).99 Paired ovarian arteries arise from the aorta caudal to the renal arteries and cranial to the deep circumflex iliac arteries. The artery supplies the ovary as well as branches to the fibrous capsule of the kidney. Caudally, it anastomoses with the uterine artery. The right ovarian vein drains into the caudal vena cava, and the left enters the left renal vein. The ovarian vein anastomoses with the uterine vein. The lymphatics drain into the lumbar lymph nodes. The nerve supply to the ovarian blood vessels is from the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system, and the nerve fibers accompany the ovarian artery to the ovary. The ovarian follicles and interstitial tissue are devoid of sympathetic innervation.10 The uterine tube, or oviduct, connects the peritoneal and uterine cavities (see Figure 109-2). It is covered by peritoneum (tunica serosa) and consists of a circular muscular layer, interspersed with longitudinal fibers, and a partially ciliated epithelium (tunica mucosa).275 The tube is 40 to 70 mm long in dogs and cats and 1 to 3 mm in diameter in dogs and is enclosed within the peritoneal fold that forms the ovarian bursa.99,232 At its ovarian end, the tube’s wide, funnel-shaped infundibulum is located near the edge of the abdominal opening into the bursa. Infundibular edges are fringed with fimbriae, which are vascular, fingerlike projections that mark the junction of peritoneum (mesosalpinx) with the mucous membrane lining of the uterine tube. In cats, the tortuous uterine tube is visible within the mesosalpinx. The uterine tube runs first in a cranial direction to the free edge of the suspensory ligament before it sharply turns caudal and continues to the apex of the uterine horn, where it terminates. The opening of the uterine tube at the horn is called the uterine ostium; at this site, the tubouterine junction acts as a regulating sphincter for sperm and blastocyst passage.166 The Y-shaped uterus consists of a neck, body, and two horns. The nonpregnant uterine size varies considerably among species but, more importantly, with previous pregnancies, stage of estrus cycle, and age.99,232 In nulliparous 11-kg dogs, the uterine horns and body average 5 to 10 mm in diameter.99 Cat uteri are usually 3 to 4 mm wide.232 The body of the uterus is located in the pelvic and abdominal cavities; in multiparous bitches, however, the uterus may be located entirely intraabdominally. The uterus is composed of three tunics, or layers: serosa, muscularis (myometrium), and mucosa (endometrium). Endometrium is the thickest of the three and consists of epithelial cells, which periodically are ciliated, and simple branched tubular glands. Myometrium consists of a thin, outer, longitudinal layer and a thick, inner, circular smooth muscle layer. A highly vascular and well-innervated zone is located in the outer portion of the circular muscle layer.99 The canine cervix lies diagonally across the uterovaginal junction, with its internal orifice facing almost entirely dorsally and external orifice directed toward the vaginal floor.99 In cats, the cervical position is relatively horizontal.111,327 The uterus receives vascular supply from anastomosing ovarian and uterine arteries. The uterine artery is a branch of the vaginal artery and enters the mesometrium at the level of the cervix close to the body of the uterus. Uterine veins follow the course of arteries. Pressure in the uterine vein is higher than in the femoral vein.42 Lymphatics of the uterus drain to hypogastric and lumbar lymph nodes. Innervation of the uterus is supplied by the pelvic plexus. Sympathetic innervation of the uterus is paired through left and right hypogastric nerves, and parasympathetic through pelvic nerves. Sectioning of hypogastric and pelvic nerves, however, does not alter the frequency or amplitude of canine uterine contractions.316 Despite similar anatomy, reproductive physiology in cats and dogs differs significantly. Similar to most domestic animals, both species go through four phases of the estrus cycle: proestrus, estrus, diestrus, and anestrus. However, the feline ovarian cycle is seasonally polyestrus, with a fifth phase “nonestrus” period during noncycling periods. The ovarian cycle of female dogs is not considered seasonal, although winter matings were most common in a Swedish study.107,125 Proestrus in cats has a much shorter duration than in dogs and, unlike in dogs, it is usually not externally visible because the feline vulva is not responsive to estrogen. The diestral phase also has distinct differences in the two species. In the cat, formation of corpora lutea requires induction of ovulation, and in nonpregnant cats, the corpus luteum remains functional for approximately 37 days.111 In contrast, dogs ovulate spontaneously; progesterone dominance is seen for 60 to 100 days in nonpregnant bitches (Figure 109-3).54,106 Unlike in other species, estrus onset or mating dates are not sufficiently accurate for parturition determination in dogs. Gestational length in bitches may range from 57 to 72 days when calculated from the first mating.57 Vaginal cytology to determine first day of diestrus likewise gave a wide range (51 to 60 days) of gestational length because diestrus shift on cytology can occur anywhere from 6 to 11 days after ovulation.161 When calculated from ovulation, however, canine gestational length was consistently 64 days.311 Ovulation is preceded by a luteinizing hormone peak, after which parturition occurs 64 to 66 days later in dogs.53 Bitches show a unique preovulatory rise in progesterone (see Figure 109-3), coinciding with the luteinizing hormone surge, that may also be used to predict gestational length. Calculated from the day serum progesterone reached 1.5 ng/mL, gestational lengths in one study were 65 ± 3 days, with no bitch giving birth outside this range.189 If the hormone status before mating is unknown, the gestational length may be predicted by ultrasonographic examination of fetal or extrafetal structures.177,190,193,194,202 Ultrasonography before or on day 39 of pregnancy gave the most accurate estimation of gestational age: 100% accuracy for 65 ± 3 days and 71% to 75% for 65 ± 1 day.190,203 Parturition was also accurately estimated during examination at late gestation in two studies using dimensions of specific fetal or placental structures.19,20 Dogs ovulate primary oocytes that must undergo two meiotic divisions, requiring 48 to 72 hours before fertilization, which usually occurs in the uterine tube around day 7 after onset of estrus.253 Fertilization takes place over a brief time period of 24 to 96 hours; thus, age differences of fetuses are not significant.43,56 Blastocysts are free floating in the ipsi- and contralateral uterine horn until day 21 to 22 after the luteinizing hormone surge and attach only 1 or 2 days before heartbeats can be detected with ultrasonography.55,56 Radiographically, canine fetal skeletons are detectable by day 42 (~20 to 21 days prepartum) and fetal pelvises by day 57; caudal vertebrae, fibula, calcaneus, and paws are visible later.50,57 During canine pregnancy, several changes are seen in common biochemical parameters of the dam. A normocytic, normochromic anemia is present because of hemodilution by increased plasma volume. Hematocrit is usually less than 40% at day 35 and less than 35% at term. Mild leukocytosis (17,000 to 26,000 white blood cells/mL), hypercholesterolemia, and hyperproteinemia have been noted.107 An acute phase response, with increased serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen concentrations, peaks around midgestation, decreases before term, and rises again after parturition.91,128 Some bitches may become hyperglycemic because of insulin resistance that becomes more pronounced during pregnancy.51 In a normal pregnant bitch, plasma progesterone decreases significantly (to below 2 to 3 ng/mL) 18 to 30 hours before parturition.47,317 Ten to 14 hours after the progesterone decrease, the body temperature of the bitch falls below 99° to 100° F.51 The rectal temperature can therefore be used as an indicator of impending parturition; however, large individual variations in temperature decrease somewhat diminish its clinical value.200,317 Parturition is divided into three stages. During stage 1, externally nonvisible uterine contractions are present; this stage lasts up to 24 hours in dogs.107 During this time, the bitch appears restless, anxious, and anorectic; shivers, pants, vomits, or paces; and may seek seclusion or exhibit nesting behavior.107 Stages 2 and 3 alternate in dogs as expulsion of each fetus (stage 2) usually is followed by expulsion of its placenta (stage 3). During these stages, visible abdominal contractions are noted. A combined duration of stages 2 and 3 may vary from a few hours up to 36 hours. Active straining, however, normally does not exceed 30 minutes before birth of a puppy, and the time lag between puppies should not exceed 4 hours.107 Twelve hours after parturition, body temperature begins to increase.317 A return to normal temperature or a marked increase in body temperature at pregnancy term without expulsion of fetuses could thus indicate abnormal parturition.107,317 After whelping is completed, the uterus involutes, returning to normal size and morphology. During involution, an odorless green, dark red-brown, or hemorrhagic vaginal discharge called lochia is normal for 4 to 6 weeks or longer. Within 4 to 6 weeks of uterine involution, discharge should gradually become more serosanguineous and the volume significantly decreased or ceased. During the entire involution, the bitch should remain healthy; if systemic signs of disease are present or an odorous discharge is noted, metritis may be present.107 Reproduction in cats has been less studied than in dogs. Although spontaneous ovulation sometimes occurs, in general, the queen must have coital stimulation to induce ovulation before corpora lutea develop and secrete progesterone. Gestation length, defined from mating to parturition, averages 66 days but may vary from 56 to 69 days.193 Breed-associated variation in gestational length has been observed.288 Variation may also be the result of ovulation induction by coitus.111 When the onset of pregnancy is defined as the first day plasma progesterone exceeds 2.5 ng/mL, the duration of pregnancy is 63 to 66 days.111 Ultrasonographic measurements of the fetus predicted correct parturition date ±2 days in seven of eight cats.21 Parturition date was also accurately predicted within 3 days in 75% of cats based on identification of fetal structures by radiography in one study.153 Interestingly, bone mineralization was detected 25 to 29 days before parturition in cats, which was approximately 1 week earlier than previously described in dogs.57,153 Similar to the case in dogs, feline oocytes are fertilized in the oviduct. Trophoblastic attachment occurs around day 15 after coitus. In contrast to dogs, in which the ovary is the sole source of progesterone secretion, placental secretion of progesterone independent of the ovaries occurs in cats after day 40.111 Information on biochemical alterations in pregnant cats is sparse; however, an anemia similar to that seen in dogs is noted after week 3 of pregnancy, with a 20% reduction in hematocrit.111 Cats undergo the same stages of parturition as dogs. A study of more than 1000 litters from pedigree cats found that time between the first and last kitten was less than 6 hours in nearly 86% of parturitions.287 In less than 1% of litters, however, parturition may be interrupted for up to 48 hours, while the queen acts as if parturition is complete.288 This phenomenon must be differentiated from dystocia. In cats, hypothermia associated with progesterone decrease occurs but is a notoriously unreliable indicator of labor onset.111 Indication and Benefits of Ovariectomy or Ovariohysterectomy A spay is defined as removal of the gonads which, in female dogs, are the ovaries. In the United States, the term spay is often used synonymously with ovariohysterectomy but can also indicate ovariectomy. In most instances of ovarian or uterine disease, surgical removal of the diseased organ by ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy is the recommended treatment. However, elective sterilization is the most common indication for ovariectomy or ovariohysterectomy in many countries. In the United States, ovariohysterectomy and castration are the most common surgical procedures performed in small animal practice.138 Overpopulation of pets is a vast problem in the United States. A survey study was conducted among more than 5000 shelters, each housing more than 100 dogs and cats, with approximately 1000 responding.228 Data from responding shelters indicated that more than 2 million dogs and cats were euthanized annually from 1994 through 1997. Because the response rate was less than 20% and did not constitute a random sample of shelters, a countrywide estimation of number of animals entering shelters or being euthanized is not possible; clearly, however, the numbers are large. Elective sterilization of dogs and cats is of dual benefit because it counteracts overpopulation by preventing reproduction and decreases the likelihood that an individual animal will be relinquished to a humane organization.187,201 It may also correct sexually dimorphic aggression, a negative behavioral interaction that occurs between females or between males housed with females.187 Nonsexual dimorphic behaviors are not usually resolved by gonadectomy. Elective sterilization reduces the risk of mammary neoplasia in dogs and cats.246,277 The risk in dogs is almost nullified if open virtual hosting or ovariectomy is performed before the first estrus.278 However, even older dogs may experience a reduced risk for mammary neoplasia.187 Older female dogs spayed within 2 years of developing mammary carcinoma experienced longer survival than intact females that developed mammary cancer.285 Also, a positive effect on survival was noted when ovariohysterectomy was performed as an adjunctive treatment for canine mammary gland carcinoma.285 Pyometra is a common disease in intact female dogs and is occasionally reported in cats.93,174 It is estimated that 23% to 24% of intact bitches require treatment for pyometra by 10 years of age.93 Elective open virtual hosting or ovariectomy, in effect, eliminates the risk of pyometra in dogs and cats unless ovarian tissue remains inadvertently.170,240,312 When ovariohysterectomy is used as treatment of pyometra, the outcome is in general excellent in dogs and cats, with survival rates exceeding 90%.93,120,151,175 The benefits and detriments of gonadectomy have been studied more thoroughly in dogs than in cats. The societal benefits of spaying pets cannot be overemphasized; however, there are some conditions that have been observed with increased frequency in gonadectomized dogs and cats compared with sexually intact animals.187 Certain tumor types, such as transitional cell carcinoma, osteosarcoma, and hemangiosarcoma, have been overrepresented in gonadectomized animals.* An exact cause-and-effect relationship has not been defined for any of these tumor types.186 Gonadectomy also increased the risk for development of diabetes mellitus in cats211,256 and hypothyroidism in female dogs.218,248 The most commonly reported factor for increasing risk of obesity is gonadectomy.† The metabolic rate has been shown to decrease after ovariohysterectomy in cats.271 Spayed female dogs have increased food intake and appetite after ovariohysterectomy, possibly from the loss of estrogen, which may act as a satiety factor.63 More than 20% of female dogs were overweight in one study, and spayed dogs were more than twice as likely to be obese than intact dogs.92 However, with an appropriate diet and exercise regimen, normal body weight can be maintained in gonadectomized animals.268 Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence is another common problem of spayed female dogs that is considered to be related to decreased estrogen concentrations.6,163,292 Urinary incontinence occurs in up to 20% of spayed bitches compared with 0.2% to 0.3% of intact bitches.164,312 However, other factors, such as breed, increasing body weight, short urethral length, and caudal bladder position, have also been suggested as risk factors for development of this disorder.* Spayed female dogs may also have an increased risk of developing urinary tract infections.278,287 Traditionally, elective Ovariohysterectomy (OHE) has been performed in the United States when the animals are 6 to 9 months of age.187,202 Efforts to reduce mass euthanasia of unwanted animals led to formation of a spay-neuter task force composed of members from the Association of Shelter Veterinarians.202 After review of the literature, the task force recommended gonadectomy of owned pets at 4 months or older after immunity to infectious agents had been developed through vaccination.202 In animals placed for adoption, however, ovariohysterectomy before adoption was recommended.187,202,242,286 The American Veterinary Medical Association has also endorsed neutering of pediatric animals (6 to 16 weeks of age).3 Because sexual maturity varies among species and breeds, a specific age that defines prepubertal surgery cannot be determined. Compared with adults, pediatric animals have an increased risk for perioperative hypothermia and hypoglycemia, immature hepatic and renal function, and greater reliance on heart rate for variability of cardiac output.100,118 Hypothermia occurs more readily in pediatric animals because of a greater body surface area : volume ratio, less subcutaneous fat, and immature shivering and vasoconstrictive reflexes.100,172 When performing ovariohysterectomy in a pediatric animal, hypothermia-induced bradycardia, deep anesthetic depth, and prolonged recovery must be avoided.100 Risk of hypothermia is reduced by warming any intravenous fluid; preventing contact with cold surfaces after premedication; using warmed, nonalcohol scrub solutions; limiting body cavity exposure; and providing heat through circulating warm water or forced-air systems.7,156,188,204,205 Pediatric animals have small reserves of glycogen in the liver and skeletal muscle and slow glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, predisposing them to hypoglycemia.100 Healthy pediatric animals should not be fasted longer than 4 hours preoperatively, and dextrose-containing fluids should be provided during surgery.100 The hepatic microsomal cytochrome P450 enzyme activity does not mature until 4.5 months of age in dogs.252,300 Also, plasma protein concentrations are lower in pediatric dogs and cats than in adult animals,172 resulting in higher unbound fractions of anesthetic agents. Therefore, drugs must be used judiciously and usually at lower doses in pediatric patients, especially when the drugs undergo hepatic metabolism or excretion.101,143 For example, the risk of renal injury attributed to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) administration may be greatly increased in neonates.143 Dogs are born with morphologically and functionally immature kidneys,98 and urine concentration in puppies up to 8 weeks of age may be lower than in adult dogs.34,113 The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system does not become functional until approximately 6 weeks of age in dogs and, until then, renal blood flow is directly correlated with arterial pressure.173,182 Therefore, fluid therapy has to be administered with care to avoid overhydration or oncotic loading.143 Anticholinergics are not recommended for routine use in pediatric animals.202 In neonates younger than 3 weeks of age, anticholinergics may be of benefit because the heart rate is positively correlated to the cardiac output.249 However, neonates also show a lack of affect with atropine administration, indicating a lack of vagal tone,117,204 and bradycardia may be mainly indicative of hypoxemia. Therefore, it may be more important to supplement oxygen than to administer parasympatholytics in neonates.143 Guidelines from the Association of Shelter Veterinarians recognize the acceptability of many variations of the spay procedure* with the requirement that both ovaries are completely removed.202 The surgical technique for prepubertal ovariohysterectomy or ovariectomy is similar to that performed in older animals. The length of the celiotomy is approximately one third of the distance between the umbilicus and pubis and centered in the middle of this distance. Normally, pediatric patients have a greater amount of serous peritoneal fluid in the abdomen. The pedicles and uterine body are ligated with encircling ligatures of fine (3-0 or 4-0), rapidly absorbable monofilament suture. If no subcutaneous fat is present, the abdominal incision is closed in two layers. With appropriate surgical technique and reasonable anesthetic duration, prepubertal ovariohysterectomy does not carry an increased risk for morbidity or mortality compared with ovariohysterectomy at the traditional age.168 In fact, an increased risk for short-term complications after ovariohysterectomy has been associated with dogs older than 2 years of age and with increasing surgery time and body weight.47,255 Long-term effects of prepubertal gonadectomy are the same as those seen after traditional gonadectomy. A study comparing the effects of ovariohysterectomy on skeletal, physical, and behavioral development found no differences after 15 months in dogs spayed at 7 weeks and those spayed at 7 months age.272 A comparison of 188 cats undergoing prepubertal gonadectomy (median age, 9 weeks) and 75 cats spayed and neutered at traditional age found no increase in long-term (median, 37 months) complications among groups.169 A study of 175 dogs (age <24 weeks; median age, 10 weeks) undergoing prepubertal gonadectomy and 153 dogs spayed or castrated at traditional age likewise found no differences in the incidence of complications 41 to 64 months after surgery.293 However, dogs gonadectomized at a prepubertal age had a greater frequency of infectious disease, most notably parvoviral enteritis. Indications for ovariohysterectomy include elective sterilization; uterine disease; and adjunctive treatment for disorders negatively affected by an intact status, including mammary neoplasia, diabetes mellitus, and epilepsy.212,257 The vast majority of procedures are performed for elective sterilization (>80% of 1712 dogs in one study).336 Several ovariohysterectomy techniques have been reported, with small differences in surgical technique.† The technique described herein44 is similar to a previously described technique159 and has been used for teaching at our institution for the past 7 years. During that time, no postoperative hemorrhage or surgery-related deaths have been recorded by the instructional animal health veterinarian at our institution.103 Technique (Figure 109-4).: The abdomen is surgically prepared from 4 cm cranial to xiphoid to 4 cm caudal to the cranial pubic brim to allow the spay incision to be extended readily as needed. Whereas subdraping by operating towels exposes the midline from xiphoid to pubis, the overlying surgical drape exposes the midline from umbilicus to pubis. A celiotomy is performed on the ventral midline, encompassing the cranial third of the distance between umbilicus to pubis in dogs older than 5 months of age. In cats older than 5 months of age and prepubertal dogs, the middle third of this distance is incised, and in prepubertal cats, the caudal third of the distance is incised. The incision is extended if visualization of ovaries or cervix is suboptimal. The uterus is located by means of an ovariohysterectomy hook or index finger. A hemostatic forceps is applied to the proper ligament and used to mark and manipulate the ovary. The ovary is grasped with fingers and mild, caudomedial traction is applied to the suspensory ligament. Primary traction is not applied to the hemostatic forceps because the proper ligament may tear. The suspensory ligament is digitally strummed as far craniodorsally as possible (near the kidney) until the ovary can be exteriorized from the abdominal cavity. The suspensory ligament does not need to be broken in all animals. Complications.: The incidences of perioperative complications from OHE in 1016 dogs and 1459 cats were 19% and 12%, respectively.255 Most were minor complications, such as inflammation of incision site and gastrointestinal upset. Of 142 bitches spayed by senior veterinary students, the total postoperative complication rate was 14%, of which wound inflammation (8.5%) and hemorrhage (2.8%) were most common.47 Complications that required intervention or treatment included inflammation or infection (8 of 142 dogs; 5.6%), hemorrhage (4 of 142 dogs; 2.8%), and pancreatitis (1 dog; 0.7%).41 The surgery time correlated significantly with occurrence of complications.47 In dogs weighing more than 25 kg, intraoperative and postoperative hemorrhage was the most common complication noted. Hemorrhage was the most common cause of death after ovariohysterectomy in large-breed dogs.25,251 Less common complications include ureteral damage, granuloma formation, and intestinal or urethral obstruction from adhesions or inappropriate ligature placement, respectively. Inadvertent ligation of a ureter may occur with inadequate visualization of the caudal pole of the kidney or the uterine body.241 Incisions should be extended as needed to ensure proper visualization. Granuloma formation at uterine or ovarian pedicle remnants has been reported in up to 28% of dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy.241,251 The use of braided nonabsorbable suture330 and nylon cable ties has been implicated; the author has also seen stump granulomas and sublumbar fistulous tracts with surgical gut ligatures. The risk for this complication may be minimized by avoiding these suture materials and reducing the amount of devitalized tissue distal to uterine stump ligatures. Adhesions rarely cause clinical problems in dogs and cats but may cause partial colonic obstruction. Postoperative inflammatory reaction can be limited with gentle tissue handling, aseptic technique, appropriate transection of the uterine body distal to the ligatures, and use of absorbable suture materials. In dogs, videoendoscopic surgery results in less postoperative pain and has a faster recovery than open procedures.69,78,152 Additional advantages of laparoscopic surgery include minimal wound inflammation,152 fewer wound infections,211 and superior visualization. Several techniques for laparoscopic or laparoscopy-assisted ovariohysterectomy have been described.64,78,333 The three-median port laparoscopy-assisted technique described below is similar to one previously described.137 Surgical Technique.: Diaphragmatic hernia must be ruled out in patients with a history of predisposing trauma, such as vehicular accidents, before creation of pneumoperitoneum. The animal is placed in a 15-degree Trendelenburg position by elevating its caudal end. A pneumoperitoneum of 10 to 12 mm Hg is established by a closed or open (Hasson) technique. Bupivacaine (0.1 to 1 mL) is infiltrated in the abdominal wall at proposed portal sites, with the lower dose used in cats. A working cannula is inserted on the midline 30 mm caudal to the umbilicus in a medium- to large-breed dog, to introduce the laparoscope. Two additional midline cannulas are placed under direct (laparoscopic) visualization at 30 to 50 mm cranial to the umbilicus and 30 to 50 mm cranial to the pubis in large-breed dogs (Figure 109-5). If a prophylactic gastropexy is performed in conjunction with ovariohysterectomy, the cranial portal may be placed 30 to 50 mm to the right of midline and 30 to 50 mm caudal to the last rib and subsequently used for the gastropexy after completion of the ovariohysterectomy. To begin laparoscopic ovariohysterectomy, a blunt probe is inserted in the most caudal portal, and the spleen and colon are retracted away from the left ovary. Visualization is aided by tilting the patient 15 degrees to the right. The ovary can often be recognized readily by very pale-colored fat deposits in the mesosalpinx. After the ovary has been identified, the blunt probe is replaced with a grasping forceps, which is used to elevate the ovary. A transabdominal suspension suture may be placed to maintain elevation of the ovary and mesovarium.78 A bipolar or ultrasonic vessel-sealing device is introduced in the most cranial portal and used to seal and transect the suspensory ligament, mesovarium, and subsequently the mesometrium with the round ligament in a cranial to caudal direction. Alternatively, hemostasis of the ovarian vessels can be achieved with pretied ligature loop, extracorporeal suture, hemoclips, or electrocautery; however, use of a sealing device has been associated with less hemorrhage and a shorter surgery time than other methods.210 Immediately after transection, the ovarian pedicle is observed for hemorrhage for 20 to 60 seconds because the site will become more difficult to visualize when the surgery is progressing. The procedure is repeated on the right side, ideally with the patient tilted 15 degrees to the left. Instead of ligation, the uterine body and associated vessels can be sealed and transected using a bipolar vessel-sealing device (Ligasure, Valleylab, Covidien, Mansfield, MA); uterine stumps sealed in this manner are able to withstand pressure greater than 300 mm Hg.17 In juvenile dogs, the uterus and ovaries may then be removed through a 12-mm cannula, negating the need for extension of the caudal portal and making the procedure entirely laparoscopic rather than laparoscope assisted. Procedure-Related Complications.: Reported complications of laparoscopic ovariohysterectomy include subcutaneous accumulation of CO2, omental herniation, seroma formation, and minor splenic or pedicle hemorrhage.14,69,152,210 Studies involving large numbers of dogs are not available; however, the complication rate seems low and has been approximated at 2%.137,186,221 Elective conversion to open laparotomy is not considered a complication; however, if performed emergently, it may be an indication of complications. The conversion rate for laparoscopic surgery in veterinary medicine is unknown.186 The most common indication for ovariectomy in veterinary medicine is elective sterilization in animals with normal uteri. Traditionally, ovariohysterectomy has been performed for this purpose in the United States, but long-term studies have failed to show significant advantage of the ovariohysterectomy compared with ovariectomy alone unless the uterus has pathologic changes.170,240,312 Because the endogenous source of progesterone has been removed, pyometra should not occur; in one study of 141 dogs ovariectomized and subsequently followed for 6 to 11 years, none developed pyometra.170,240 Exogenous administration of progestins should be avoided in ovariectomized and ovariohysterectomized dogs because hormonal influence on the uterus could lead to development of cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra or stump pyometra, respectively. Other long-term complications such as urinary incontinence and obesity are not significantly different for ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy; therefore, ovariectomy is an acceptable procedure for elective sterilization of dogs and cats with healthy uteri.312 During ovariectomy, a midline incision, localization of the ovary, and ligation of the ovarian vessels proceed as described above for ovariohysterectomy. In addition, the uterine artery and vein are ligated and transected at the level of the proper ligament, immediately cranial to the uterine horn. If the uterus appears abnormal, the procedure should be converted to ovariohysterectomy. Complications of ovariectomy are the same as described under ovariohysterectomy. Vaginal bleeding was observed in a case in which the ovariectomy inadvertently resulted in a transected uterine horn.312 Care should be taken to transect through the mesosalpinx cranial to the uterine horn. Laparoscopic-assisted ovariectomy may be performed with a three-portal technique, as described above for ovariohysterectomy, or through a two-portal approach.137 A scope portal is established 30 to 50 mm caudal to the umbilicus, and an instrument portal is placed midway between the scope portal and the pubis. If a 12-mm cannula (with a reducer if combined with 5-mm instruments) is used caudally, small ovaries can be removed through the cannula. After grasping the ovary, a transabdominal suspension suture is placed to maintain the ovary in a suspended position. A bipolar or ultrasonic vessel-sealing device is introduced through the caudal portal, and the proper ligament, uterine tube, mesosalpinx, mesovarium, and suspensory ligament are transected in a caudal to cranial direction. The ovary may be removed through the caudal cannula, if size allows. Alternatively, it is removed together with the cannula through the caudal portal incision; the cannula is reinserted and the abdomen reinsufflated for retrieval of the second ovary. Complications of laparoscopic ovariectomy are similar to those discussed for laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy. The rate of complications with this technique is currently unknown. Unless they are grossly enlarged, the ovaries are not palpable in dogs or cats, and imaging is often necessary to assess their size and structure. Normal ovaries are not visible on radiographic examination; however, a mass effect may be seen caudal to the kidney with ovarian enlargement, and calcification in that region may be consistent with a teratoma.181 The ultrasonographic appearances of the canine reproductive tract and ovarian tumors are well described.36,82,94,135,254 Cystic masses with regular contours are more often found in benign conditions.82 Intravenous pyelography can help differentiate ovarian from renal masses.181 The value of advanced imaging for diagnosing ovarian disease has not been determined. No consistent laboratory findings are noted with ovarian disease. Persistently high estrogen concentration or a single, low serum luteinizing hormone concentration in a bitch indicates an intact status or ovarian remnants if the animal was spayed more than 10 days earlier.199 Estrogen-induced cell cornification detected on vaginal smear cytology may be indicative of functional neoplasia, cysts, or ovarian remnants.110,181 Chronically increased plasma estrogen concentrations (>20 pg/mL) may be indicative of follicular cysts or estrogen-producing tumors.254 Animals with luteinized follicular cysts will have increases in progesterone with normal estrogen concentrations and no signs of proestrus or estrus.181 Transabdominal needle biopsy of the ovaries is not recommended because of the propensity of many ovarian tumors to implant and grow on the peritoneal surface.181 The ovaries are explored through a standard ventral midline celiotomy (see Ovariectomy above) or laparoscopic technique. The feline ovary is usually readily visible; in dogs, fat deposits in the mesovarium commonly obscure the ovary. The ovarian bursa is incised to expose a normal-sized ovary. The bursal incision is closed with synthetic absorbable suture.295 Ovarian neoplasms account for approximately 1% of all neoplasms.59 Ovarian tumors are uncommon, partly because of the high rate of ovariectomy and ovariohysterectomy in many countries.5,49 The tumors may be germ cell, epithelial, or sex cord stromal in origin. Metastasis is uncommon; however, ovarian tumors are prone to transcoelomic seeding. Small ovarian tumors are located close to the caudal pole of the kidney and are difficult to discern on radiographic examination. Larger tumors are pendulous and mimic any midabdominal mass in location.181 Evidence of calcification may indicate a teratoma.145 Metastases are rarely noted on thoracic radiographs.181 Abdominal ultrasonography is highly sensitive for the detection of ovarian masses.82,135,254 Abdominal fluid, if present, can be aspirated for cytologic evaluation to confirm malignant effusion; however, transabdominal ovarian aspiration is not recommended because of the risk for seeding the peritoneal surfaces.181 Canine ovarian tumors usually occur in middle-aged to older animals and are almost exclusively primary, with only a couple of reports of metastatic lesions.* Epithelial and sex cord stromal neoplasia account for the vast majority of canine ovarian tumors.† Epithelial cell tumors include papillary adenoma and adenocarcinoma, cystadenoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma. These tumors comprise 40% to 50% of reported canine ovarian neoplasms.59,233,234,236,250 Papillary tumors are the only canine ovarian tumors that are occasionally bilateral.233,234,250 Papillary adenocarcinoma may be associated with widespread peritoneal implantation and malignant abdominal effusion or thoracic effusion if metatasized.181 Metastasis of papillary adenocarcinoma has been noted in renal and paraaortic lymph nodes, omentum, liver, and lungs.59 Cystadenomas originate from rete ovarii, are unilateral, and consist of multiple thin-walled cysts with a watery content.161,241 Undifferentiated carcinomas are nonfunctional and of embryonic morphology; their origin cannot be determined. The most common sex cord stromal tumor is the granulosa cell tumor, which accounts for approximately 50% of ovarian tumors in several reviews.181 These tumors may produce estrogen, progesterone, or both. They are usually unilateral, firm, and lobulated with cysts and can grow quite large.59,250 Up to 20% of granulosa cell tumors metastasize.181 Thecomas, which are granulosa cell tumors in which stroma predominates, are generally benign. Granulosa cell tumors can be histogenetically marked by α-inhibin.208 Bitches with granulosa cell tumors may present with clinical signs of persistent proestrus or estrus, cystic endometrial hyperplasia, or pyometra. Dysgerminomas, teratomas, and teratocarcinomas are germ cell tumors. They are the least common of the canine ovarian tumors, representing 6% to 12% of ovarian tumors in this species.59,251 Dysgerminomas have been associated with a metastatic rate of 10% to 30%, including mainly abdominal lymph nodes but also liver, kidney, omentum, pancreas, and adrenal glands.59,76,139,188,234 The prognosis of all types of ovarian tumors is very similar. When single, nonmestastasized tumors are completely excised, the prognosis is good. Chemotherapy may lengthen survival times in canine patients with metastatic disease.181 Dogs with estrogen-secreting granulosa cell tumors may develop bone marrow aplasia and, possibly, irreversible pancytopenia. As with dogs, feline ovarian tumors are of epithelial, germ cell, or sex cord stromal origin. Sex cord stromal tumors are most commonly reported, and more than 50% of granulosa cell tumors are malignant in cats.181,238,291 As in dogs, feline granulosa cell tumors are often large and unilateral and produce hormones. They metastasize to peritoneum, lumbar lymph nodes, omentum, diaphragm, kidney, spleen, liver, and lungs.8,127,238 Dysgerminomas constitute approximately 15% of feline ovarian tumors. They are not hormone producing and are slow to metastasize but do so in up to 33% of cases.127 Epithelial tumors are rare in cats.127,238 The prognosis in cats with ovarian tumors is unknown but is likely similar to other species.181 Nonfunctional periovarian cysts are incidental findings. Rudimentary embryonic remnants of the male epididymidis and deferent duct (epoophoron) and tubules of the testis (paroophoron) are associated with the uterine tube in the mesosalpinx. In females, these structures represent the embryonic mesonephros and mesonephric (Wolffian) duct. Whereas the epoophoron may give rise to pedunculated cysts on the fimbriae, paroophoron may give rise to cysts in the mesosalpinx.99 These cysts must be differentiated from ovarian cysts. Ovarian follicular cysts are lined with granulosa cells. Follicular cysts that secrete significant amounts of estrogen produce prolonged proestrus; if small amounts of progesterone are also secreted, they produce signs of prolonged estrus. Luteinized cysts secrete only progesterone, resulting in prolonged diestrus. Functional ovarian cysts are more commonly seen in dogs younger than 3 years of age and cats younger than 5 years of age. In dogs, follicular cysts are associated with vaginal bleeding and attractiveness to males beyond the normal 21 to 28 days of an ovarian cycle.68,110 If the cyst is also progesterone producing, persistent standing heat is evident. Cats often show persistent estrus when follicular cysts are present.111 Physical examination findings are consistent with persistent proestrus or estrus and include an enlarged vulva and vaginal bleeding of uterine origin. Follicular cysts are diagnosed by vaginal cytology in dogs and hormone concentrations in dogs and cats. The presence of more than 80% superficial cells on a vaginal smear is indicative of increased serum estrogen concentration. Dogs with follicular cysts have progesterone concentrations greater than 2 ng/mL, and affected cats and dogs have plasma estrogen concentrations chronically greater than 20 pg/mL. Abdominal ultrasonography is usually diagnostic and helps to rule out differential diagnoses such as pyometra. Normal preovulatory follicles measure 4 to 9 mm in diameter.215 Functional cysts are 10 to 50 mm in diameter and usually solitary, although they can be bilateral. Bilateral estrogen-producing cysts may be indicative of a disturbance of the hypothalamic pituitary–ovarian axis.110 Luteinized cysts can be single or multiple and unilateral or bilateral.110 Cysts may spontaneously resolve; therefore, treatment is not always required.110 Bitches with high breeding value and estrogen-producing tumors have been treated with gonadotropins (i.e., gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] or human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG]). However, failure of medical management may be common, but ovariectomy is curative.110 Failure of medical management may also indicate a functional ovarian neoplasia.215,243 Early surgical treatment minimizes risks associated with prolonged endogenous estrogen, such as bone marrow suppression. In valuable breeding animals, cyst resection can be attempted. Separation of the cyst from the ovary is commonly not possible, however; in that case, ipsilateral ovariectomy is performed, and fertility is maintained by the contralateral, normal ovary.110 Aspiration of bilateral follicular cysts by open laparotomy approach was successful in one bitch.105 Luteinized cysts are usually only partially responsive to prostaglandin F2α, and surgical removal of the cysts, ovary, or both is recommended. Ovarian remnant syndrome in women is related to chronic or repeated pelvic inflammatory conditions that produce dense fibrotic adhesions between the ovary and peritoneum, making ovariectomy technically more challenging.206,280 This is seldom the case in dogs and cats, nor has ectopic or accessory ovarian tissue been diagnosed in these species.117,323 In small animals, the syndrome most often results from improper surgical technique; decreased visualization by an inappropriately limited incision increases the risk.323 Ovarian tissue could also revascularize if dropped into the abdomen. Cats may be overrepresented with this condition and constituted 63% in a review of 46 cases.217,324 Clinical signs of ovarian remnants are primarily those of recurrent estrus (e.g., vulvar enlargement in dogs, attraction of males, and willingness to breed in both species).110,240,251 Vaginal discharge is not commonly seen and is associated with remnant uterine tissue if present.110,324 The diagnosis in dogs is based on a history of ovariohysterectomy and vaginal cytology, if performed during standing heat, indicative of estrogen dominance.110 Other diagnostic tests in dogs include hormone assays: remnant ovarian tissue is likely present if serum estradiol and progesterone concentrations exceed 15 pg/mL and 2 ng/mL, respectively.110 A single low luteinizing hormone hormone concentration indicates functioning ovarian tissue in dogs.199 A high luteinizing hormone concentration is usually consistent with gonadectomy; however, false-positive results may occur.199 Cats show more subtle vaginal cytology changes than dogs.217 In cats, an increased plasma estrogen concentration is suggestive of ovarian remnants or adrenocortical problems.111 Progesterone analysis for confirmation of ovarian remnants in cats requires previous luteinization by administration of human chorionic gonadotropin (250 IU IM) or GnRH (25 µg IM).111 Ovarian remnants are confirmed if progesterone concentration exceeds 2.5 ng/mL 5 to 7 days after luteinization. Treatment includes surgical removal of tissue located at both ovarian pedicles. Care should be taken to avoid damage to the ureters. Visualization of ovarian remnants may be improved during estrus or diestrus because of the presence of follicles or corpora lutea. Referral to a surgical specialist has been recommended because experience is imperative in finding the remnants.110

Ovaries and Uterus

Anatomy and Physiology

Ovaries and Ligaments

Uterine Tube

Uterus

Reproductive Physiology

Pregnancy and Parturition in Dogs

Pregnancy and Parturition in Cats

Surgery

Consequences of Ovariohysterectomy

Prepubertal Ovariohysterectomy

Pediatric Physiology Relevant to Surgery

Surgery and Outcome

Ovariohysterectomy

Open Surgical Approach

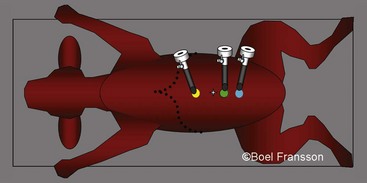

Laparoscopic Ovariohysterectomy

Ovariectomy

Open Technique

Laparoscopic Technique

Disorders of the Ovary

Imaging

Clinical Pathologic Parameters in Ovarian Disease

Surgical Exploration

Ovarian Neoplasia

Diagnosis and Staging

Canine Ovarian Tumors

Feline Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian Cysts

Functional Cysts

Ovarian Remnant Syndrome

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree