CHAPTER 7 Oral Cavity, Gastrointestinal Tract, and Associated Structures

Endoscopy has facilitated increased access to the mucosal surface of the gastrointestinal tract and enhanced the application of diagnostic cytology for its evaluation. It is an especially useful adjunct procedure when combined with the histologic examination of tissue for the complete assessment of gastrointestinal tract. The cytologic and histologic findings tend to be disparate when: (1) the specimens are obtained from different sites, (2) the lesion is deeply located in the lamina propria or submucosa precluding exfoliation, (3) surface-associated findings are lost during processing of the histologic sample, and (4) cell or tissue distortion (artifact) is present in either the cytologic or the histologic specimen.

In our experience, both touch imprint and brush cytologic preparations can provide useful information when concurrently examined with the histologic specimen (Jergens et al., 1998). Brush cytology tends to exfoliate more cells but also has the potential to induce hemorrhage and introduce leukocytes that may be mistaken for inflammation. Brush cytology often represents pathology of the deeper lamina propria compared to touch imprints, which reflect the surface and mucosal changes. The criteria that differentiate benignity and malignancy must be carefully evaluated when examining esophageal and gastrointestinal cytologic specimens since the cellular atypia associated with epithelial hyperplasia and regeneration as a consequence of inflammation can mimic epithelial neoplasia.

ORAL CAVITY

Normal Cytology

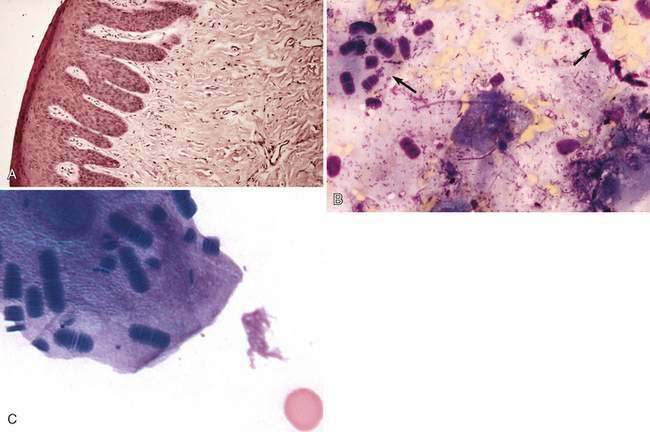

Superficial and intermediate squamous epithelial cells are the commonly exfoliated cell type for the buccal cavity and the surface of the tongue (Fig. 7-1A). A variety of oropharyngeal bacteria can be seen in samples from the oral cavity. Noteworthy is Simonsiella sp. (Fig. 7-1B&C). Neutrophils are normally lost via transmigration through the mucous membranes into the oral cavity and may be observed in low numbers.

Inflammation

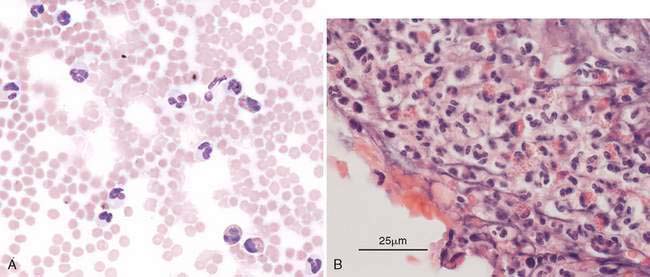

Inflammatory diseases that can affect the oral cavity include immune-mediated diseases such as bullous disease, foreign bodies, dental disease, systemic manifestation of uremia, and bacterial, viral, and fungal infections (Guilford, 1996a). The inflammatory exudate can be composed of leukocytes, necrotic debris, and bacterial flora. Some raised plaque-like oral lesions with ulcerated surface will contain a pure eosinophilic population or mixed with eosinophils and neutrophils. Reports of an ulcerative eosinophilic stomatitis in the Cavalier King Charles spaniels (Fig. 7-2A&B) suggest this eosinophilic inflammatory response may occur concurrent with other affected systems and represent a hypersensitivity response in this breed (Joffe and Allen, 1995; German et al., 2002). In another condition, the undersides of the tongue may occasionally display a raised white mass which cytologically in addition to normal epithelium contains variable amounts of fine to coarse crystalline material. Most often it is extracellular but many crystals can be found within macrophages (Fig. 7-3A&B). This macrophagic or granulomatous (if giant cells are observed) inflammation is typical of a lingual calcinosis circumscripta. While urates may be considered, calcium is typical and can be confirmed with Von Kossa stain (Fig. 7-3C) or Alizarin red S (Marcos et al., 2006).

Neoplasia

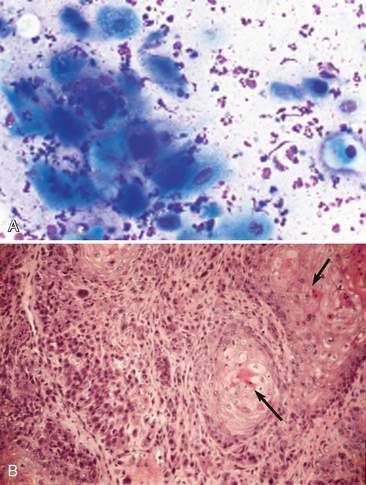

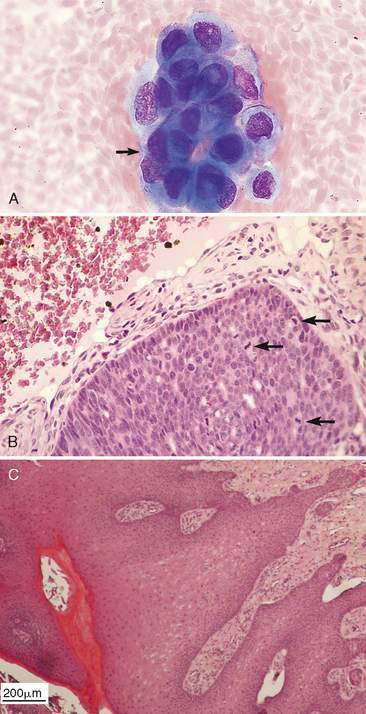

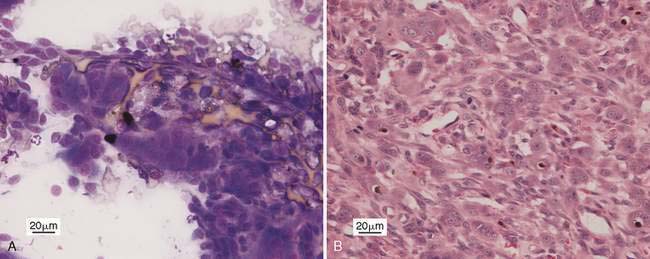

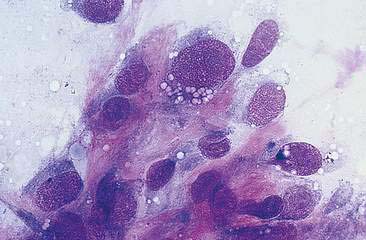

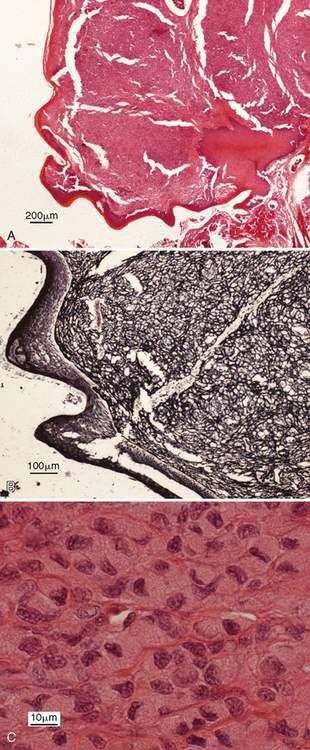

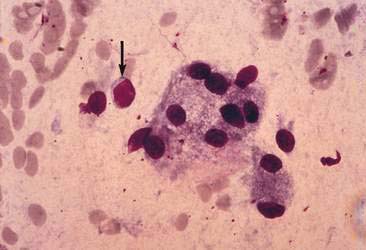

Epithelial, mesenchymal, and discrete (round) cell neoplasia can involve the oral cavity. As in other organ systems, the diagnostic sensitivity of cytology is highest for discrete cell neoplasia and lowest for mesenchymal tumors. This is due to reduced exfoliation and the difficulty differentiating neoplastic mesenchymal cells from reactive fibrocytes/fibroblasts that compose inflammatory/reparative lesions. Discrete cell neoplasia includes lymphoma, mast cell tumor, plasmacytoma, transmissible venereal tumor, and histiocytoma. The plasmacytoma can involve the oral mucous membranes, tongue, or mucosa of the digestive tract and be difficult to diagnose definitively without immunocytochemical or immunohistochemical characterization (Rakich et al., 1989). The most common epithelial neoplasm is squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 7-4A&B). Less common is epithelial odontogenic neoplasia (Poulet et al., 1992) (Fig. 7-5A–C). Squamous cell carcinoma can occur anywhere in the oral cavity but in cats it often occurs in the frenulum of the tongue with early metastasis to the regional lymph nodes. An epulis is a common gingival mass of dogs or cats that can be a developmental, hyperplastic, inflammatory (Fig. 7-6A&B), or neoplastic lesion. A study of feline epulides (de Bruijn et al., 2007) determined the multinucleate cells of the giant cell epulis likely reflect an inflammatory response through osteoclast formation from mononuclear macrophages. These can be confusing lesions to evaluate cytologically because they can be composed of dental epithelial nests enrobed in stromal fibrous tissue. When the diagnosis is in doubt cytologically, it is prudent to pursue an excisional biopsy. Oral melanomas often are malignant and infiltrative, may contain abundant or only minimal pigment (amelanotic melanomas), and rapidly metastasize to the regional lymph nodes (Head et al., 2002) (Fig. 7-7A–C). Fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma (Fig. 7-8) are the mesenchymal tumors that more commonly involve the oral cavity. Fibroma, hemangiosarcoma, and liposarcoma are less frequent (Bernreuter, 2008). Fibrosarcomas of the mandible and maxilla occasionally can have cytologic and histologic benign morphologic features but demonstrate aggressive biologic behavior (Ciekot et al., 1994). Neoplasia detected in the soft or hard palate may be extensions from the nasal cavity. In a study of lingual lesions (Dennis et al, 2006), about 4% of the cases in dogs involved the granular cell tumor, tumor of varied histogenesis (Head et al., 2002). Granular cell tumors (Fig. 7-9A–C) are mostly associated with the tongue than elsewhere in the oral cavity of older dogs and may occur in the cat as well. It is thought the majority of granular cell tumors arise from neuroectodermal origin and are set within reticulin fibers. Tumors appear as a sessile raised firm white mass which act benign. Cytologically, cells are individualized with eccentric nucleus with abundant eosinophilic or strongly periodic acid-Schiff-positive cytoplasmic phagolysosomal granules.

SALIVARY GLAND

Normal Cytology

Cytologic evaluation of salivary gland disease is diagnostically rewarding. The salivary gland also may be sampled accidentally when attempting to aspirate the submandibular lymph node. Cytologically, the salivary gland contains uniform secretory epithelial cells that are clustered and/or individual with eccentric, dark basophilic nuclei, and clear, vacuolated to foamy cytoplasm (Fig. 7-10). The cytoplasmic staining of the cells differs between serous cells (distinguishable) and mucous cells (may appear clear). Individual epithelial cells can be difficult to differentiate from macrophages, however, they have uniformly clear to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and do not contain phagocytic material. Eosinophilic-staining mucus is commonly observed and when present may cause erythrocytes to “stream” or line up in parallel rows (Fig. 7-11).

Inflammation

The most common inflammatory lesion is caused by a salivary mucocele (sialocele) or ranula. A ranula is a cystic distension of an epithelial lined duct in the floor of the mouth. A sialocele is an accumulation of salivary secretions in nonepithelial lined cavities adjacent to the duct. While the cause is not known, trauma plus a developmental predisposition is proposed. The accumulated saliva stimulates an inflammatory reaction that changes over time. The initial inflammatory influx is composed of neutrophils and macrophages along with secretory epithelial cells set in an eosinophilic to basophilic mucus background (see Fig. 7-11). Lymphocytes replace the neutrophilic component and can become a prominent feature. Although the foamy macrophages can appear morphologically similar to the plump secretory epithelial cells, differentiation is not necessary when formulating the cytologic impression.

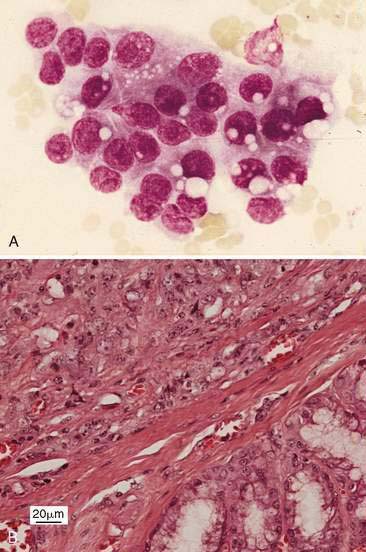

Neoplasia

The salivary adenocarcinoma is uncommon and demonstrates the general characteristics of epithelial malignancy that range from relatively well-differentiated to marked pleomorphism (Fig. 7-12A&B) (Spangler and Culbertson, 1991). The neoplastic epithelial cells can form acinar structures and some of the cells can have abundant retained cytoplasmic secretions that displace the nucleus to the periphery, forming a cell that appears similar to a signet ring. Mixed salivary neoplasms are rare and contain both neoplastic epithelial cell and mesenchymal cell components that can include bone and cartilage.

PANCREAS

Normal and Hyperplasia Cytology

The pancreas is not usually sampled unless a mass is detected. Cellular characteristics can rapidly deteriorate owing to extracellular pancreatic enzyme activity associated with pancreatitis. Hyperplastic nodules (see Fig. 2-4) can appear cytologically similar to normal epithelium. In these cases, the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is higher and nucleoli may be prominent.

Inflammation

Pancreatitis may cause focal abdominal fluid accumulations or effusions with the characteristics of either a modified transudate or a sterile purulent exudate (Fig. 7-13). If a proteinaceous background is present, it can have a “dirty,” moderately basophilic appearance that corresponds to saponified fat observed histologically. A hemorrhagic effusion is occasionally noted. Pancreatic cysts or abscesses can be detected as intra-abdominal masses and sampled by ultrasound-guided aspiration. The samples are often sterile and composed of neutrophils embedded in a proteinaceous background (Salisbury et al., 1988).

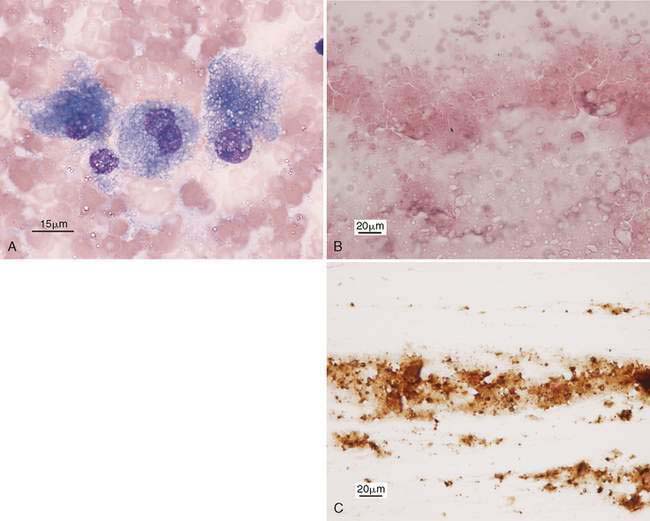

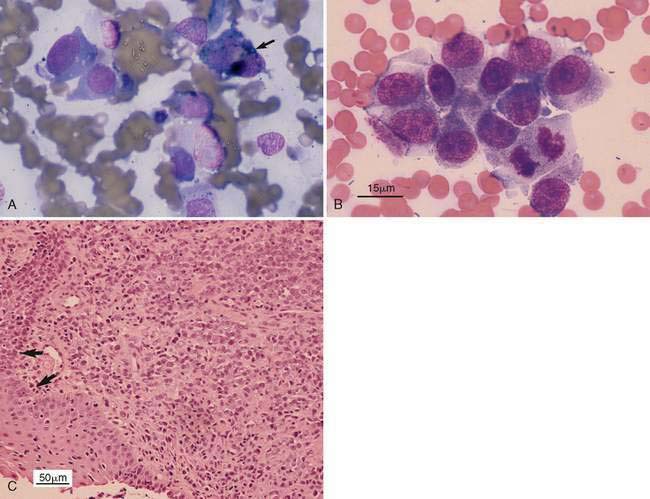

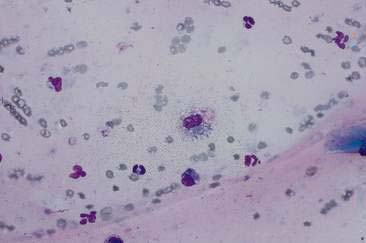

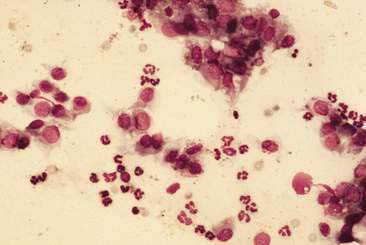

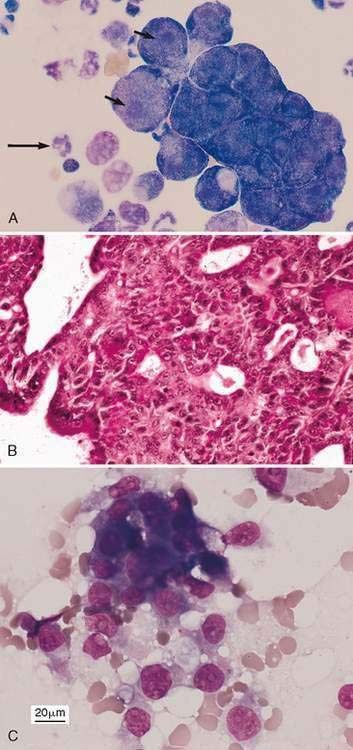

Neoplasia-Exocrine Pancreas

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma can be diagnosed directly via ultrasound-guided cytology/biopsy. It is a diagnostic consideration when carcinoma cells are observed in an abdominal effusion or in a thoracic effusion secondary to their metastasis via the diaphragmatic lymphatics. The pancreatic adenocarcinoma has characteristics similar to those of other adenocarcinomas, including a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleolus, fine cytoplasmic vacuolization, cytoplasmic hyperchromatic basophilia, and a tendency to form acinar structures (Fig. 7-14A–C).

ESOPHAGUS

Normal Cytology

The mucosal layer of the esophagus has a stratified squamous epithelium that contains openings for the ducts of the esophageal mucous glands. Exfoliated stratified squamous epithelial cells can either appear angular or have the rounded shape of intermediate epithelial cells and basal cells with eccentric nuclei. Large numbers of basal epithelial cells can indicate trauma, inflammation, or erosion (Green, 1992). The stromal cells and glandular cells usually do not exfoliate. Samples from the gastroesophageal region may contain squamous epithelium mixed with gastric columnar epithelium. Ingesta with oropharyngeal flora consisting of a mixed bacterial population of rods, cocci, and Simonsiella sp. may be noted in esophageal samples (see Fig. 7-1).

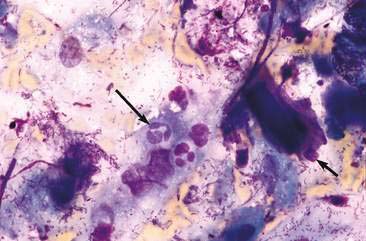

Inflammation

Reflux esophagitis most commonly involves the distal esophagus. It is caused by the action of regurgitated gastric (pepsin and acid) and possibly duodenal (bile acids and pancreatic enzymes) secretions that have a corrosive effect on the stratified squamous epithelium. Esophageal inflammation has a prominent neutrophilic component (Fig. 7-15) and the epithelial cells show reactive hyperchromasia, or nuclear and cytoplasmic degenerative changes. Esophageal inflammation is suggested if oropharyngeal contamination is not present and the site sampled appears inflamed endoscopically.

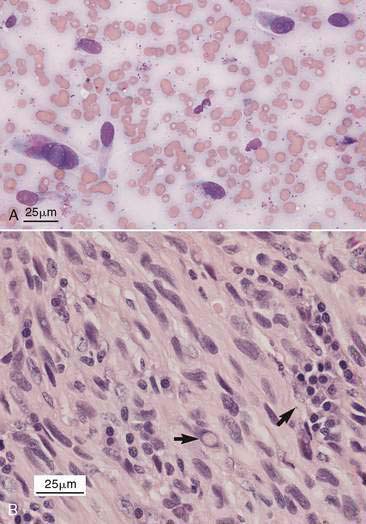

Neoplasia

The differential considerations for esophageal masses include the neoplasia and parasitic granuloma. Squamous cell carcinoma has neoplastic features that vary from relatively well differentiated to anaplastic. Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas can be difficult to differentiate from hyperplasia, but the presence of bizarre cell forms along with variable nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, variable cytoplasmic basophilia, and fine cytoplasmic vacuolization support a neoplastic cell population. An adenocarcinoma of the esophageal glands is a less common epithelial neoplasm. Its location and cytologic features can be similar to a thyroid carcinoma. Spirocerca lupi is a spirurid nematode that parasitizes the esophageal wall of dogs in warm climates where the dung beetle serves as the intermediate host. Endoscopically, the mass appears as a smooth, nonulcerated firm tumor. It can be diagnosed by finding embryonated eggs in a fecal flotation. Pleomorphic spindle-shaped cells exfoliated from the granuloma are easily mistaken for sarcoma. In fact, esophageal sarcomas are usually associated with the presence of the parasite (Fox et al., 1988). Another spindle-shape sarcoma is an esophageal leiomyosarcoma in which the cells may contain eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules as well as nuclear glycogen vacuoles and pleomorphism (Fig. 7-16A&B).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree