CHAPTER 7 Nasal Exudates and Masses

INDICATIONS

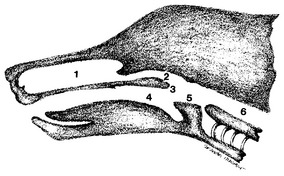

Detailed examination of the nasal cavity and most sample collections are optimally performed while the animal is under general anesthesia, with an endotracheal tube in place and the cuff inflated. Radiographs and rhinoscopy should be performed before biopsy or flushing techniques so that radiographic detail and visualization are not altered by resulting hemorrhage and manipulation of the nasal tissues.1 The major landmarks and communication of the airways and food passages are schematically indicated (Figure 7-1).

The nasal cavity may be examined with equipment that varies from simple to sophisticated. In some animals, an otoscope may be used to examine the rostral nares; however, a flexible 4-mm fiberoptic endoscope should be used to view the ventral nasal meatus or nasopharynx.2 The oronasal cavity can be examined by retracting the soft palate with forceps and using a dental mirror or flexible endoscope. These procedures can aid visualization of abnormal tissues but copious exudates or hemorrhage may preclude adequate examination.

SAMPLING TECHNIQUES

For the nasal flushing technique, the depth of the nasal cavity is estimated and a soft rubber catheter is passed caudad through the external nares or retrograde from caudal to the nasopharynx. A syringe containing about 10 ml of nonbacteriostatic sterile saline is attached to the catheter and multiple flushes are performed using intermittent positive and negative pressure.1,2 Dislodged particulate matter can be caught in a gauze sponge placed caudal to the soft palate or rostral to the nares, depending on the direction of the flushing procedure. Aqueous cytologic material can be collected within the syringe barrel by aspiration.

Aspiration, the second means of obtaining samples from the nasal cavity, is useful when a mass is localized radiographically or visually. This technique involves use of a large-gauge polypropylene urinary catheter, a Sovereign plastic needle guard (Monoject, Sherwood Medical, St. Louis), or a tomcat catheter cut at a 45-degree angle to form a sharp cutting edge.3 Proper catheter length is determined by measuring the distance from the external nares to the medial canthus of the eye. Catheter length is important to prevent penetration of the cribriform plate during the procedure. The catheter is attached to a syringe and advanced into the nasal cavity until moderate resistance is felt. Suction is applied while several advances are made into the mass. Gentle negative pressure is maintained as the catheter is removed from the mass and nasal cavity to retain solid tissue fragments.

Cytologic preparations are made from touch imprints or squash preparations of tissue fragments, smears of flush samples and swabs, and smears of centrifuged nasal flush sediments. These preparations are air-dried, stained, and examined by routine methods. (See Chapter 1 for further discussion concerning specimen preparation and staining.) A portion of the samples can be reserved for microbiologic culture and sensitivity testing if an infectious agent is suspected or found on stained cytologic preparations. If samples are used for microbiologic testing, a sterile swab or sterile tube should be submitted that does not contain an anticoagulant such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), because EDTA can be bacteriostatic. If the fluid is submitted for cytologic examination, EDTA is useful for preservation of cell morphology. After imprinting for cytologic evaluation, tissue fragments can be preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathologic evaluation.

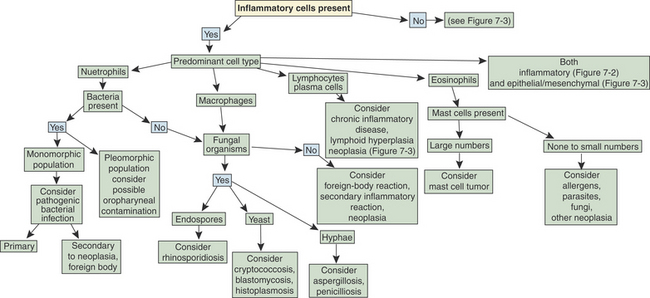

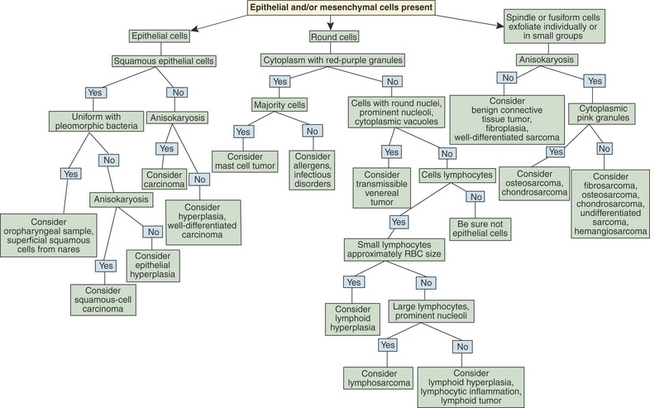

Flow charts are provided to aid in the evaluation of nasal cytologic smears containing primarily inflammatory cells (Figure 7-2) and those containing primarily epithelial and/or mesenchymal cells (Figure 7-3).

NORMAL CYTOLOGIC FINDINGS

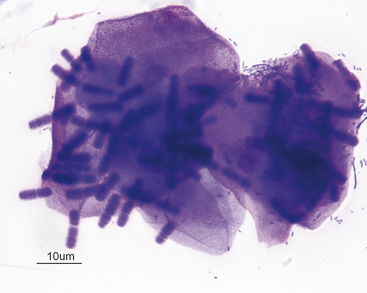

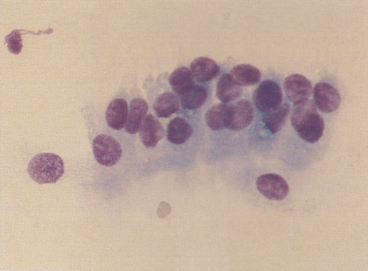

It is important to distinguish normal from pathologic cells and bacterial populations in cytologic preparations. In nasal flush specimens, oropharyngeal organisms of variable morphology and epithelial cells may be obtained from healthy animals. Simonsiella spp. are large, stacked, rod-shaped bacteria that are inhabitants of the oral cavity of dogs and cats and are seen commonly in smears contaminated by oral secretions (Figure 7-4).4 Epithelial cell morphology varies with the site and depth of the specimen. Nonkeratinized squamous epithelial cells, often with adherent bacteria, are obtained from the external nares and oropharynx. Ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells and associated mucus originate from the nasal turbinates (Figure 7-5). Basal epithelial cells are smaller and rounded and have darker blue cytoplasm (Figure 7-6). Hemorrhage during sampling results in the presence of red blood cells (RBCs) and white blood cells (WBCs) in similar proportions to peripheral blood (about 1 WBC for every 500 to 1000 RBC).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree