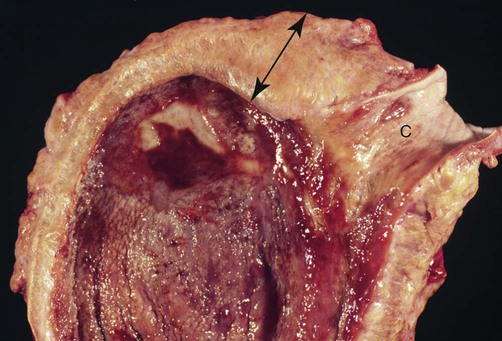

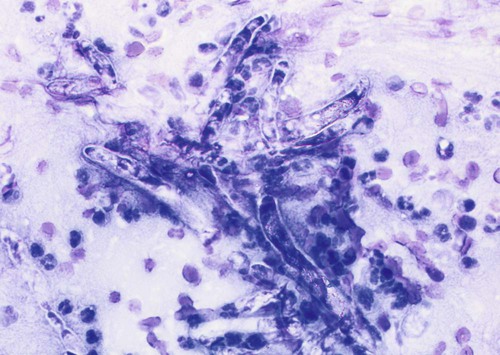

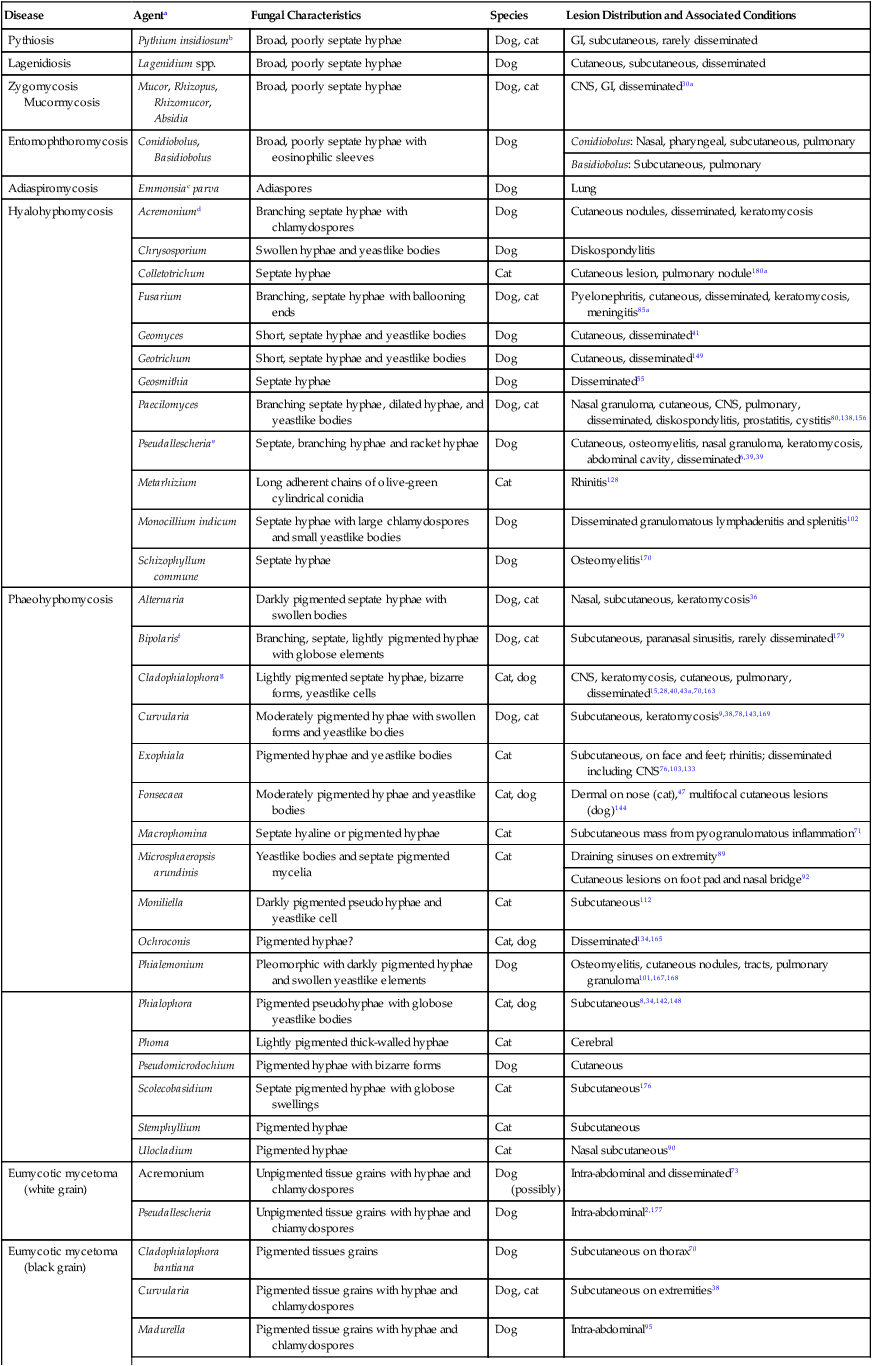

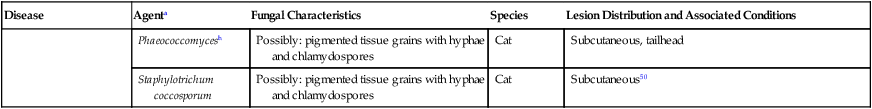

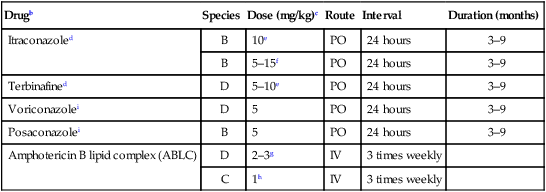

Infections caused by miscellaneous fungal and pseudofungal pathogens include pythiosis and lagenidiosis, which are caused by aquatic pathogens in the class Oomycetes, and many opportunistic fungal infections that affect dogs and cats sporadically. Although identification of specific fungal pathogens is usually impossible without culture, these infections can often be categorized to some degree on the basis of their morphologic features, such as pigmentation, hyphal diameter, and septation in tissue. Infections caused by opportunistic fungi are generally classified by the form of the fungal elements in tissue and whether they are pigmented; for example, phaeohyphomycosis is caused by pigmented hyphal forms, hyalohyphomycosis by unpigmented hyphal forms, and eumycotic mycetoma by fibrosing granuloma with tissue grains containing pigmented or unpigmented fungal elements. The diseases and agents are summarized in Table 65-1. TABLE 65-1 Miscellaneous Fungal Infections of Dogs and Cats CNS, Central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal. aAn excellent resource for taxonomic synonyms is www.doctorfungus.org. bSynonyms: Hyphomyces destruens, P. destrans, P. gracile. An oomycete in the kingdom Stramenopila. eSynonyms: Petriellidum; Allescheria; Scedosporium apiospermum (anamorph). fSynonyms: Cladosporium, Drechslera. gSynonyms: Cladosporium bantianum, Xylohypha bantiana, Torula bantiana, Cladosporium trichoides. Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomycosis are caused by a taxonomically diverse group of pathogens but share similar clinical and histologic characteristics; all cause lesions characterized by pyogranulomatous and eosinophilic inflammation associated with broad, sparsely septate hyphae (see Table 65-1). Because of these similarities, they were previously grouped together in the category of phycomycosis. Although phycomycosis is a convenient label for cases in which a definitive culture-based diagnosis has not been made, the term is no longer an appropriate taxonomic designation and should be replaced in current literature with the more specific terms pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomycosis. The obsolete term chromomycosis occasionally still appears in the veterinary literature as a synonym for either phaeohyphomycosis or chromoblastomycosis, the latter of which has not yet been described in animals.20 Another difficulty for clinicians is the confusion that arises from taxonomic revisions in medical mycology, which results in confusing synonymy in fungal nomenclature. Excellent resources for updated fungal nomenclature can be found in the literature33 and online.129 A much higher prevalence of cutaneous and systemic opportunistic mycotic infections has been associated with increased use of ciclosporin to treat disorders such as immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, and inflammatory central nervous system (CNS) disease.169 In the authors’ experience, mycotic infections are much more prevalent in animals being treated with multiple immunosuppressive medications (including ciclosporin), than in animals being treated with ciclosporin alone. The most common sign in such animals is the development of cutaneous phaeohyphomycosis or hyalohyphomycosis. However, disseminated infection has also been observed. Pythiosis is best known as a cause of gastrointestinal (GI) or cutaneous disease in dogs45,122 and of cutaneous granulomas in horses.25 It has also been described as an uncommon cause of cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions in cats13,35,58,174 and calves124 and of arteritis, keratitis, or periorbital cellulitis in people.5,84,160,175 A rare case of primary pulmonary pythiosis was described in a jaguar (Panthera onca).21 Pythium insidiosum31 is an aquatic pathogen belonging to the class Oomycetes in the kingdom Stramenopila (Chromista). Pythium species and other oomycetes differ from true fungi in producing motile, flagellate zoospores and having cell walls that contain cellulose and β-glucan but not chitin. In addition, ergosterol is not an important component of the oomycete cell membrane. Furthermore, members of the genera Pythium and Lagenidium are sterol auxotrophs—they incorporate sterols from their environment rather than producing them. Other members of the genus Pythium are plant pathogens of some economic importance. Based on molecular studies, the pathogens most closely related to oomycetes are the Prototheca spp.93 The infective stage of P. insidiosum is thought to be the biflagellate aquatic zoospore, which is released into warm water environments and likely causes infection by encysting in damaged skin or GI mucosa.58 Although the specific factors that favor sporulation of P. insidiosum in the environment are unknown, some evidence suggests that certain types of plant material may be involved in the life cycle as a natural host.121 In the United States, pythiosis is encountered most often in the Gulf Coast states but has been recognized with some frequency in animals living as far north as New Jersey, Virginia, Kentucky,113 southern Illinois, and southern Indiana and as far west as Oklahoma, Missouri, and Kansas. Surprisingly, GI pythiosis has also been confirmed in a number of dogs living in Arizona59 and California.12 Globally, pythiosis is most often encountered in Southeast Asia (especially Thailand and Indonesia), eastern coastal Australia, New Zealand, and South America but has also been recognized in Korea, Japan, and the Caribbean. Pythiosis is most often identified in young, large-breed male dogs and is especially common in outdoor working breeds such as Labrador retrievers.44 Affected dogs have been identified more often in the fall, winter, and early spring than in the late spring and summer months.122 In cats, specific breed and sex predilections have not been apparent in the few described infections. However, of 11 cats with cutaneous pythiosis diagnosed through the authors’ laboratory, six were younger than 10 months old, with an age range of 4 months to 9 years.60 Infected dogs often have a history of recurrent exposure to warm, freshwater habitats. However, some infections develop in suburban house dogs with no known access to a standing body of water. Because P. insidiosum zoospores have been shown to have an affinity for damaged skin,116 it is likely that animals with cutaneous wounds or injury to GI mucosa are more likely to become infected. However, solid epidemiologic evidence to support this assumption is lacking. Other risk factors for the development of pythiosis have not been identified. Affected animals are typically immunocompetent and otherwise clinically healthy. Clinical signs caused by P. insidiosum infection are the result of cutaneous or GI lesions, or of disease extension into adjacent tissues or regional lymph nodes. Cutaneous and GI lesions are rarely found together in the same patient. Systemic dissemination of pythiosis has only been described once.45 Cutaneous pythiosis in dogs and cats typically causes nonhealing wounds and invasive masses that contain ulcerated nodules and draining tracts (Figs. 65-1 and 65-2).45,174 Affected dogs are usually taken to the veterinarian because of solitary or multiple cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions involving the extremities, tailhead, ventral neck, perineum, or medial thigh. When present, regional lymphadenomegaly often reflects extension of infection rather than just reactive inflammation. Lesions in 11 cats with cutaneous pythiosis evaluated through the authors’ laboratory have included subcutaneous masses (some of which were highly invasive) in the inguinal, tailhead, or periorbital regions, and draining nodular lesions or ulcerated plaquelike lesions on the extremities (see Fig. 65-1), occasionally centered on the digits or footpad. Two cats with pythiosis had large subcutaneous masses affecting the extremities and cranioventral thorax but no cutaneous involvement.174 In a third case, P. insidiosum infection resulted in nasal cavity and nasopharyngeal lesions and bilateral retrobulbar masses.13 GI pythiosis in dogs is characterized by severe segmental transmural thickening of the stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, or (although rarely) the esophagus or pharyngeal region (Fig. 65-3).44,75,122,136 Mesenteric lymphadenomegaly is common and occasionally observed without accompanying GI tract lesions. The gastric outflow area, duodenum, and ileocolic junction are the most frequently affected portions of the GI tract, and it is not uncommon to find two or more segmental lesions in the same patient. Inflammation in affected regions is typically centered on the submucosa, with variable mucosal ulceration and occasional extension of disease through serosal surfaces, resulting in adhesion formation and peritonitis. Involvement of the mesenteric root may cause severe enlargement of mesenteric lymph nodes, which are often embedded in a single, large, firm granulomatous mass that is palpable in the midabdomen. Extension of disease into mesenteric vessels may result in bowel ischemia, infarction, perforation, or acute hemoabdomen.137 In addition, infection may extend from the GI tract into contiguous tissues such as the pancreas and uterus.44,122 In one report, a prostatic abscess caused by P. insidiosum was observed in a dog with an adjacent colonic lesion.85 Clinical signs associated with GI pythiosis include weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, hematochezia, or all of these symptoms. Physical examination abnormalities are a very thin body and a palpable abdominal mass. Signs of systemic illness such as lethargy or depression are not typically present unless intestinal obstruction, infarction, or perforation occurs. Similar to clinical signs observed in dogs, those of GI pythiosis in cats have been attributed to partial intestinal obstruction, palpable abdominal masses, and mesenteric lymphadenomegaly.145 Isolation of P. insidiosum from infected tissues is not difficult when appropriate sample handling and culture techniques are used. For best results, unrefrigerated tissue samples should be wrapped in a sterile saline-moistened gauze sponge, shipped at ambient temperature, and arrive at the laboratory within 24 hours of collection. However, when samples cannot be processed for more than 2 days after collection, they should be shipped with ice packs, stored in the refrigerator, or stored at ambient temperature in an antibacterial solution to decrease proliferation of bacterial contaminants.68 The use of selective media significantly increases the likelihood of isolating pathogenic oomycetes. The authors routinely use vegetable extract agar68 amended with streptomycin (200 µg/mL) and ampicillin (100 µg /mL) for the isolation of P. insidiosum. As a commercially available alternative, Campy blood agar (Remel, Inc., Lenexa, KS), which contains trimethoprim, vancomycin, polymyxin B, cephalothin, and amphotericin B (AMB), is also effective. Small pieces of fresh, nonmacerated tissue should be placed directly on the surface of the agar and incubated at 37° C (98.6° F); growth is typically observed within 12 to 24 hours. Although the identification of oomycetes is generally based on morphologic features of sexual reproductive structures such as oogonia and antheridia, isolates of P. insidiosum rarely produce these structures in vitro. Therefore, identification of P. insidiosum should be based on colonial and hyphal characteristics; growth at 37° C; production of motile, reniform, biflagellate zoospores; and if possible, specific PCR amplification or ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing. Colonies on vegetable extract, Sabouraud’s dextrose, or cornmeal agar are typically submerged, are white to colorless, and have an irregular radiate pattern.10,32 Microscopically, hyphae are broad (4 to 10 µm in diameter), hyaline, sparsely septate, and tend to branch at right angles. Zoospores can be readily produced by placing boiled grass blades on the surface of a 1- to 2-day-old colony growing on 2% water agar, incubating at 37° C for 18 to 24 hours, and then placing the infected grass blades in a dilute salt solution.26,51,51 After 2 to 4 hours of incubation at 37° C, terminal vesicles from which zoospores are released can be seen extending from the cut edges of the infected grass blades. Although the production of zoospores is an important supporting feature for the identification of pathogenic oomycetes, it is not specific for P. insidiosum. Immunoblot analysis has been used successfully to identify sera from Pythium-infected horses,118 dogs,91 and cats145 that react to antigens of P. insidiosum, and has the added advantage of high specificity and sensitivity. In addition, a soluble mycelial antigen-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of anti-P. insidiosum antibodies in dogs and cats has been found to be highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of pythiosis.65 As well as providing a means for early, noninvasive diagnosis, the ELISA also appears to be useful for monitoring response to therapy in affected patients. A dramatic decrease in antibody levels approaching the range of clinically healthy animals is typically observed 2 to 3 months after successful surgical resection of infected tissues. In contrast, antibody levels remain high in animals that have a clinical recurrence after surgical treatment. Therefore, the ELISA appears to be a promising tool for the early detection of postoperative recurrence and may also be used to guide the duration of postoperative medical therapy. To circumvent the difficulties associated with obtaining a culture-based diagnosis of pythiosis, a P. insidiosum–specific PCR assay has been developed.61 This assay can be applied to DNA extracted either from cultured isolates or from appropriately preserved infected tissue samples.182 In addition, this technique has been successfully used with DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues sections.85 The major advantage of this assay is its high specificity. Immunohistochemical techniques based on polyclonal antibodies17,136 have been used regularly during the past 15 years as confirmatory tests for pythiosis. An advantage of these techniques is that they can be used with paraffin-embedded tissues, permitting the evaluation of archival samples. However, at least one of these antibodies has demonstrated cross-reactive staining when used to evaluate tissues from dogs with conidiobolomycosis94 and lagenidiosis.64 Therefore, the specificity of this antibody for the immunohistochemical diagnosis of pythiosis may be questionable. A newer polyclonal anti–P. insidiosum antibody raised in chickens and adsorbed with sonicated Lagenidium and Conidiobolus hyphae appears to be highly specific for the immunohistochemical detection of P. insidiosum hyphae in tissues.67 A presumptive diagnosis of pythiosis, lagenidiosis, or zygomycosis can occasionally be established cytologically if lesions are accessible (Fig. 65-4). Cytologic examination of exudate from draining tracts, impression smears made from ulcerated skin lesions, and fine-needle aspirates of enlarged lymph nodes often reveal pyogranulomatous, suppurative, or eosinophilic inflammation (or all of these). In addition, macerated tissue fixed in 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) may be examined microscopically for the presence of typical wide, poorly septate, branching hyphal elements. Histologic findings associated with pythiosis are characterized by eosinophilic granulomatous to pyogranulomatous inflammation with fibrosis. Affected tissues typically contain multiple foci of necrosis surrounded and infiltrated by neutrophils, eosinophils, and macrophages. In addition, discrete granulomas composed of epithelioid macrophages, plasma cells, multinucleate giant cells, and fewer neutrophils and eosinophils may be observed.44,45,45 Vasculitis is occasionally present. Organisms are usually found within areas of necrosis or at the center of discrete granulomas.122 Although P. insidiosum hyphae are difficult to visualize on sections stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain, they may be identified as clear spaces (hyphal ghosts) surrounded by a narrow band of eosinophilic material.122 Hyphae are easily visualized in sections stained with Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS) but not with periodic acid–Schiff. They are broad (mean, 4 µm; range, 2 to 7 µm), rarely septate, and occasionally branching.45,122 Cutaneous pythiosis typically causes severe nodular to diffuse ulcerative dermatitis and panniculitis. Because areas of inflammation are most often found in the deep dermis and subcutis, wedge biopsies are preferred to punch biopsies when pythiosis is suspected. Similarly, because inflammation in GI pythiosis centers on the submucosal and muscular layers rather than mucosa and lamina propria,122 the diagnosis of pythiosis may be missed on endoscopic biopsies that fail to reach deeper tissues. Therefore, pythiosis should be considered as a diagnostic possibility when endoscopic biopsies reveal eosinophilic or pyogranulomatous inflammation without identification of an etiologic agent. Local postoperative recurrence of pythiosis is common and can occur either at the site of resection or in regional lymph nodes. For this reason, combination medical therapy with itraconazole (ITZ) and terbinafine is recommended for at least 2 to 3 months after surgery (Table 65-2). To monitor for recurrence, ELISA serology should be performed before and 2 to 3 months after surgery. In animals that have had a complete surgical resection and do not have a recurrence of disease, serum antibody levels drop significantly within 3 months of surgery.65 If this occurs, medical therapy can be discontinued. If antibody levels remain elevated 2 to 3 months after surgery, medical therapy should be continued, with periodic reevaluation of ELISA serology. TABLE 65-2 Drug Therapy for Miscellaneous Fungal Infectionsa B, Both dog and cat; C, cat; D, dog; PO, by mouth; IV, intravenous. aIncluding pythiosis, lagenidiosis, zygomycosis, hyalohyphomycosis, and phaeohyphomycosis. bSee the Drug Formulary in the Appendix for more information on these drugs. cDose per administration at specified interval. dCombination of itraconazole and terbinafine recommended for treatment of pythiosis and lagenidiosis. eRecommended dose when combined with itraconazole for pythiosis and lagenidiosis. fRecommended dose for zygomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, and hyalohyphomycosis. gFor a cumulative dose of 24 to 27 mg/kg. hFor a cumulative dose of 12 mg/kg. iDose based on anecdotal information; no pharmacokinetic data available for dogs or cats. Because of reported neurotoxicity reported for voriconazole, higher dosing is not recommended. Medical therapy for pythiosis has traditionally been unrewarding, likely because ergosterol (the target for most currently available antifungal drugs) is generally lacking in the oomycete cell membrane. Despite this fact, clinical and serologic cures have been obtained using medical therapy with ergosterol-targeting drugs in a small number of P. insidiosum–infected dogs, as well as with an infection in a 2-year-old child.160 In the authors’ experience, a small number of dogs with nonresectable or partially resected GI pythiosis have responded to ITZ, AMB lipid complex, or a combination of ITZ and terbinafine (see Table 65-2). Although the overall percentage of animals responding is low (less than 20%), based on our subjective observations, the combination protocol seems superior to ITZ or AMB alone. Caspofungin, the first antifungal in the newly developed echinocandin class of β-glucan synthase inhibitors to gain United States Food and Drug Administration approval, has the potential to be a more effective drug for the treatment of oomycosis because of the large amount of β-glucan present in the oomycete cell wall. However, the susceptibility of the form of β-glucan synthase present in P. insidiosum to inhibition by caspofungin is unknown. Results of two studies were moderate caspofungin-induced inhibition of in vitro growth of P. insidiosum, even at high concentrations.18,139 In rabbits, experimentally infected with P. insidiosum and treated with caspofungin intraperitoneally for 20 days, measurable disease progression slowed during treatment, but lesions quickly resumed growth when the drug was discontinued.139 Considered together with the extremely high cost of the drug itself, these results are not encouraging regarding the potential clinical usefulness of caspofungin for the treatment of pythiosis. See the Drug Formulary in the Appendix and Chapter 55 for more information on caspofungin. A vaccine derived from soluble mycelial antigens and secreted exoantigens of P. insidiosum has been used successfully to treat cutaneous granulomas in horses and vasculitis in people.82,173 Unfortunately, although controlled trials have not been completed, the efficacy of Pythium vaccines in dogs appears to be poor, and clinical improvement has not been observed in any of the authors’ patients. The limited published information available regarding the efficacy of Pythium vaccines in dogs is anecdotal.117 In one canine case report that suggested a vaccine-related therapeutic effect,77 tissues were submitted to Louisiana State University that were obtained after the initial diagnostic wedge biopsies but before vaccine administration. The tissue culture was negative for oomycetes and failed to show any hyphae in multiple GMS-stained sections, suggesting that the disease may have been resolving before the vaccine administration.57 Interestingly, the authors of this chapter are aware of one additional dog in which lesions associated with cutaneous pythiosis resolved completely without additional therapy after incomplete surgical resection.

Miscellaneous Fungal Infections

Disease

Agenta

Fungal Characteristics

Species

Lesion Distribution and Associated Conditions

Pythiosis

Pythium insidiosumb

Broad, poorly septate hyphae

Dog, cat

GI, subcutaneous, rarely disseminated

Lagenidiosis

Lagenidium spp.

Broad, poorly septate hyphae

Dog

Cutaneous, subcutaneous, disseminated

Zygomycosis Mucormycosis

Mucor, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, Absidia

Broad, poorly septate hyphae

Dog, cat

CNS, GI, disseminated30a

Entomophthoromycosis

Conidiobolus, Basidiobolus

Broad, poorly septate hyphae with eosinophilic sleeves

Dog

Conidiobolus: Nasal, pharyngeal, subcutaneous, pulmonary

Basidiobolus: Subcutaneous, pulmonary

Adiaspiromycosis

Emmonsiac parva

Adiaspores

Dog

Lung

Hyalohyphomycosis

Acremoniumd

Branching septate hyphae with chlamydospores

Dog

Cutaneous nodules, disseminated, keratomycosis

Chrysosporium

Swollen hyphae and yeastlike bodies

Dog

Diskospondylitis

Colletotrichum

Septate hyphae

Cat

Cutaneous lesion, pulmonary nodule180a

Fusarium

Branching, septate hyphae with ballooning ends

Dog, cat

Pyelonephritis, cutaneous, disseminated, keratomycosis, meningitis85a

Geomyces

Short, septate hyphae and yeastlike bodies

Dog

Cutaneous, disseminated41

Geotrichum

Short, septate hyphae and yeastlike bodies

Dog

Cutaneous, disseminated149

Geosmithia

Septate hyphae

Dog

Disseminated55

Paecilomyces

Branching septate hyphae, dilated hyphae, and yeastlike bodies

Dog, cat

Nasal granuloma, cutaneous, CNS, pulmonary, disseminated, diskospondylitis, prostatitis, cystitis80,138,156

Pseudallescheriae

Septate, branching hyphae and racket hyphae

Dog

Cutaneous, osteomyelitis, nasal granuloma, keratomycosis, abdominal cavity, disseminated6,39,39

Metarhizium

Long adherent chains of olive-green cylindrical conidia

Cat

Rhinitis128

Monocillium indicum

Septate hyphae with large chlamydospores and small yeastlike bodies

Dog

Disseminated granulomatous lymphadenitis and splenitis102

Schizophyllum commune

Septate hyphae

Dog

Osteomyelitis170

Phaeohyphomycosis

Alternaria

Darkly pigmented septate hyphae with swollen bodies

Dog, cat

Nasal, subcutaneous, keratomycosis36

Bipolarisf

Branching, septate, lightly pigmented hyphae with globose elements

Dog, cat

Subcutaneous, paranasal sinusitis, rarely disseminated179

Cladophialophorag

Lightly pigmented septate hyphae, bizarre forms, yeastlike cells

Cat, dog

CNS, keratomycosis, cutaneous, pulmonary, disseminated15,28,40,43a,70,163

Curvularia

Moderately pigmented hyphae with swollen forms and yeastlike bodies

Dog, cat

Subcutaneous, keratomycosis9,38,78,143,169

Exophiala

Pigmented hyphae and yeastlike bodies

Cat

Subcutaneous, on face and feet; rhinitis; disseminated including CNS76,103,133

Fonsecaea

Moderately pigmented hyphae and yeastlike bodies

Cat, dog

Dermal on nose (cat),47 multifocal cutaneous lesions (dog)144

Macrophomina

Septate hyaline or pigmented hyphae

Cat

Subcutaneous mass from pyogranulomatous inflammation71

Microsphaeropsis arundinis

Yeastlike bodies and septate pigmented mycelia

Cat

Draining sinuses on extremity89

Cutaneous lesions on foot pad and nasal bridge92

Moniliella

Darkly pigmented pseudohyphae and yeastlike cell

Cat

Subcutaneous112

Ochroconis

Pigmented hyphae?

Cat, dog

Disseminated134,165

Phialemonium

Pleomorphic with darkly pigmented hyphae and swollen yeastlike elements

Dog

Osteomyelitis, cutaneous nodules, tracts, pulmonary granuloma101,167,168

Phialophora

Pigmented pseudohyphae with globose yeastlike bodies

Cat, dog

Subcutaneous8,34,142,148

Phoma

Lightly pigmented thick-walled hyphae

Cat

Cerebral

Pseudomicrodochium

Pigmented hyphae with bizarre forms

Dog

Cutaneous

Scolecobasidium

Septate pigmented hyphae with globose swellings

Cat

Subcutaneous176

Stemphyllium

Pigmented hyphae

Cat

Subcutaneous

Ulocladium

Pigmented hyphae

Cat

Nasal subcutaneous90

Eumycotic mycetoma (white grain)

Acremonium

Unpigmented tissue grains with hyphae and chlamydospores

Dog (possibly)

Intra-abdominal and disseminated73

Pseudallescheria

Unpigmented tissue grains with hyphae and chiamydospores

Dog

Intra-abdominal2,177

Eumycotic mycetoma (black grain)

Cladophialophora bantiana

Pigmented tissues grains

Dog

Subcutaneous on thorax70

Curvularia

Pigmented tissue grains with hyphae and chlamydospores

Dog, cat

Subcutaneous on extremities38

Madurella

Pigmented tissue grains with hyphae and chlamydospores

Dog

Intra-abdominal95

Phaeococcomycesh

Possibly: pigmented tissue grains with hyphae and chlamydospores

Cat

Subcutaneous, tailhead

Staphylotrichum coccosporum

Possibly: pigmented tissue grains with hyphae and chlamydospores

Cat

Subcutaneous50

Pythiosis

Etiology

Epidemiology

Clinical Findings

Diagnosis

Culture

Serologic Testing

Molecular Assays

Immunohistochemistry

Pathologic Findings

Therapy

Drugb

Species

Dose (mg/kg)c

Route

Interval

Duration (months)

Itraconazoled

B

10e

PO

24 hours

3–9

B

5–15f

PO

24 hours

3–9

Terbinafined

D

5–10e

PO

24 hours

3–9

Voriconazolei

D

5

PO

24 hours

3–9

Posaconazolei

B

5

PO

24 hours

3–9

Amphotericin B lipid complex (ABLC)

D

2–3g

IV

3 times weekly

C

1h

IV

3 times weekly

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine