Jennifer S. Taintor

Lymphoma

Lymphoma, also known as lymphosarcoma or malignant lymphoma, is a hematopoietic neoplasm arising from lymphoid tissue, including lymph nodes, spleen, and gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Terminology regarding this neoplasm is confusing. Historically, the term leukemia was used to denote a progressive neoplastic transformation within the bone marrow of either the lymphoid or myeloid cell lines. Although lymphoma is classified as a lymphoproliferative disease, it originates in lymphoid tissue and may progress to infiltrate bone marrow, at which point it is referred to as lymphoma with leukemia or leukemic lymphoma. Leukemia in the horse is rare, but the reports in the literature indicate that horses can develop neoplasia in either the lymphoid or myeloid cell lines.

In human medicine, lymphoma is classified as either Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma on the basis of cytologic evaluation of an aspirate or biopsy sample. Although both arise from lymphoid tissue, Hodgkin’s lymphoma is distinguished from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells, a giant cell usually derived from B lymphocytes. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is the most common form of lymphoma identified in domestic animals. Similar to the situation in human medicine, following identification of lymphoma, veterinary oncologists attempt to further categorize non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by immunophenotyping neoplastic lymphocytes as B cell, T cell, or natural killer (NK) cell. This classification allows for diagnosis, disease classification, prognosis prediction, therapeutic selection, and monitoring of disease progression.

Incidence and Epidemiology

Lymphoma was first reported in a horse in 1858, and now is the most commonly diagnosed hematopoietic neoplasm in horses worldwide. The overall incidence of lymphoma is 1.3% to 2.8% of all equine tumors, and its prevalence is 0.002% to 0.5% in the equine population. There is no breed or sex predilection, and any age of horse can be affected, but most cases are reported in horses 4 to 10 years old. No specific risk factors have been identified, and although there appears to be no genetic predisposition for development of lymphoma, the neoplasm has been reported in an aborted fetus and in two foals younger than 1 year. Previous reports speculating that malignant transformation of a retrovirus may be a cause of equine lymphoma are questionable because of failure of viral infection to fulfill Koch’s postulates for development of lymphoma.

Clinical Aspects

Equine lymphoma is classified into the following clinical syndromes: multicentric or generalized, alimentary, mediastinal, cutaneous, and solitary tumors of extranodal sites. Although clinical signs reflect the function of the organ involved and the degree and duration of involvement, common clinical signs for all forms of equine lymphoma include weight loss, depression, lethargy, edema of the ventral portion of the body wall or distal limb, recurrent fever, and lymphadenopathy if peripheral lymph nodes are involved. Clinical signs of lymphoma typically develop insidiously but can arise acutely, depending on organ involvement. Unfortunately, in most affected horses lymphoma is diagnosed late in the course of the disease because of the neoplasm’s insidious nature and the lack of pathognomonic clinical signs. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with equine lymphoma have been reported and include pruritus, pyrexia, cachexia, erythrocytosis, and hypercalcemia. Paraneoplastic syndromes likely are a result of tumor-derived circulating hormones or cytokines or are caused by an immunologic response to the tumor. Occasionally, the paraneoplastic syndrome may precede or mask clinical signs suggestive of lymphoma or can potentially interfere with treatment of primary disease.

Multicentric Lymphoma

Multicentric lymphoma, the most common form of lymphoma in horses, is characterized by widespread involvement of peripheral or internal lymph nodes and a variety of organs. This form of lymphoma is most likely spread through lymphatic circulation. Liver, spleen, intestine, kidney, and bone marrow (with leukemic lymphoma) are the organs most commonly affected, but lymphomas of the upper airway, central nervous system, heart, adrenal glands, reproductive organs, and eye have also been reported. Clinical signs of multicentric lymphoma reflect the function of organs involved, and multiple clinical signs may be present concurrently. Horses with the multicentric form of lymphoma commonly have weight loss, edema of the ventral body wall, enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), and high temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate. Additional signs of multicentric lymphoma that may be observed include abdominal distension, icterus, malabsorption syndrome, hematuria, and polydipsia and polyuria. Involvement of the central nervous system results in various neurologic signs, including ataxia, cranial nerve deficits, Horner’s syndrome, urinary or fecal incontinence, or seizures. In one report of horses with ataxia caused by epidural lymphoma of the cervical and thoracic region, masses in the eyelids, larynx, or intraarticular surface of multiple joints were also present. Ocular manifestations associated with multicentric lymphoma include intermittent eyelid swelling that may shift from one eye to the other, chronic ocular discharge, edematous third eyelid, unilateral exophthalmos, corneoscleral masses, and chronic uveitis that is unresponsive to treatment. Syndromes such as pseudohyperparathyroidism and paraneoplastic pruritus and alopecia also have been reported in horses with multicentric lymphoma.

Alimentary Lymphoma

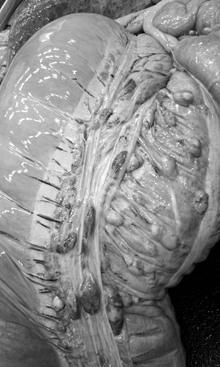

Approximately 10% to 20% of all horses with lymphoma have the alimentary form, and unlike the mean reported age for horses with lymphoma, alimentary lymphoma is seen in older horses (mean age, 16 years). The small intestine is more commonly involved than the large intestine, but multiple segments of both small and large intestine can be affected and lead to involvement of other organs or lymph nodes. This often makes alimentary lymphoma difficult to differentiate from the multicentric form (Figure 96-1). Alimentary lymphoma is likely to affect multiple segments of intestine in younger horses (<10 years), whereas focal intestinal lesions are more likely to occur in older horses. Weight loss, lethargy, and anorexia are the most common features of alimentary lymphoma, but some affected horses also have abdominal pain or diarrhea caused by malabsorption and protein-losing enteropathy.

Mediastinal Lymphoma

Mediastinal lymphoma, also known as thoracic or thymic lymphoma, is the most common neoplasm of the thorax and has been found in horses of all ages. Besides the common clinical signs encountered with all lymphomas, horses with mediastinal lymphoma may also have respiratory distress, coughing, and distension of the jugular vein. Auscultation of the chest may reveal muffled heart sounds, and evidence of pleural fluid can be detected during thoracic percussion and ultrasonography. Thoracoscopy is an effective method of identifying possible masses within the thoracic cavity and obtaining a diagnostic biopsy specimen.

Cutaneous Lymphoma

Cutaneous lymphoma is characterized by multifocal subcutaneous nodules that may exude a yellow-colored fluid and become alopecic and ulcerated (Figure 96-2). Common sites of cutaneous lymphoma are the head, limbs, trunk, and perineum. It has been anecdotally reported that in some mares, nodules regress during pregnancy but reappear after foaling.

Solitary Tumors of Extranodal Sites

Numerous case reports document solitary lymphoid tumors in horses. Reported sites of these tumors include the spleen, heart, palate, nasopharynx, nasal passage, sinus, tongue, mandible, eyes, meninges, mammary tissue, uterus, and pelvis. A retrospective study of extraocular lymphoma in horses found either single nodular or diffuse lesions associated with the eyelid, third eyelid, cornea, conjunctiva, and sclera. Of the 26 cases in that report, 14 had nodular lesions and 12 had diffuse lesions; among those horses, 1 had multicentric lymphoma and 3 had cutaneous lymphoma. The third eyelid was the most common extraocular structure involved, and both nodular and diffuse lesions were seen at that site. Extraocular lymphoma tumors were bilateral in 8 of the 26 horses.

Diagnosis

Initial investigation of a horse with suspected lymphoma should include physical examination, palpation of accessible abdominal organs per rectum, complete blood count, and serum biochemical tests. Ultrasonographic examination of the thorax and abdomen may aid in locating a mass and the extent of organ and localized lymph node involvement. Aspiration or biopsy of affected lymph nodes or masses is ideal for diagnosis but may be difficult if the suspected site lies within the thorax or abdomen. Although cells rarely exfoliate from lymphoma, cytologic examination of fluid collected by centesis of body cavities may provide a diagnosis. Biopsy or aspiration through laparoscopy or thoracoscopy, or aspiration under ultrasonographic guidance, may be necessary for cytologic or histologic diagnosis.

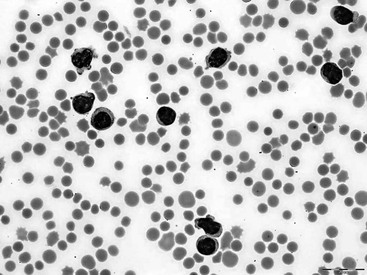

Horses with lymphoma are usually anemic as a result of premature destruction of antibody-coated erythrocytes, inadequate production of erythrocytes because of myelophthisis, anemia of chronic inflammation, or blood loss through intestinal ulceration. Erythrocytosis, however, was reported in one horse with lymphoma and was attributed to paraneoplastic production of erythropoietin. Although rare, erythrocytosis has also been reported in humans and dogs with lymphoma. Leukocytosis, if present, is a result of neutrophilia, which is likely caused by tumor necrosis. Rarely is the lymphocyte count increased, but when affected horses are leukemic, atypical or abnormal immature lymphocytes are seen during cytologic examination of the peripheral blood smear (Figure 96-3). The abnormal immature lymphocytes are larger than neutrophils, have an increased number of nuclei, and contain chromatin that is not densely packed. Other cytologic abnormalities reported in the peripheral blood smear of leukemic horses include Heinz bodies and Sézary cells, which are medium to large lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei that resemble monocytes and have scant cytoplasm. Other blood dyscrasias observed with malignant infiltration of bone marrow include thrombocytopenia and pancytopenia. Serum biochemical abnormalities commonly encountered include hyperfibrinogenemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperglobulinemia. Human lymphoma cells have increased production of the cytokine interleukin-6, and it is likely that increased concentration of fibrinogen in blood of horses with lymphoma is a result of a similar increase in cytokine production by neoplastic lymphocytes. Hypoalbuminemia is commonly observed and is most likely a result of protein-losing enteropathy, especially in horses with alimentary lymphoma. Horses with lymphoma of the liver may have decreased production of albumin. A decrease in serum albumin concentration may also be the result of a compensatory reaction to increased serum globulin concentrations, which is likely the result of the immune response to lymphoma antigen. Although hypercalcemia can occur with lymphoma, many horses with lymphoma are hypocalcemic because they are hypoalbuminemic.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree