CHAPTER 4 Lymphoid System

The lymphoid organs commonly examined by cytology include the peripheral and internal lymph nodes, spleen, and occasionally the thymus. As a result of their similar cell populations, the following cytodiagnostic categories are used. It should be noted that more than one presentation might occur in a specimen at a time.

LYMPH NODES

Indications for Lymph Node Biopsy

TABLE 4-1 Selected Peripheral Lymph Nodes in the Dog

| Lymph Node | Location | Drainage Features |

|---|---|---|

| Submandibular | Group of two to four nodes located ventral to the angle of the jaw | Includes most of the head, including the rostral oral cavity |

| Prescapular | Group of two or three nodes located in front of the supraspinatus muscle | Includes the caudal part of the head (pharynx, pinna), most of the thoracic limb, and part of the thoracic wall |

| Axillary | One or two nodes located caudal and medial to the shoulder joint | Includes most of the thoracic wall, deep structures of the thoracic limb and neck, and the thoracic and cranial abdominal mammary glands |

| Superficial inguinal | Two nodes located in the furrow between the abdominal wall and the medial thigh | Includes the caudal abdominal and inguinal mammary glands, ventral half of the abdominal wall, penis, prepuce, scrotal skin, tail, ventral pelvis, and medial part of the thigh and stifle |

| Popliteal | One node located behind the stifle | Includes areas distal to the stifle |

Aspirate and Impression Biopsy Considerations

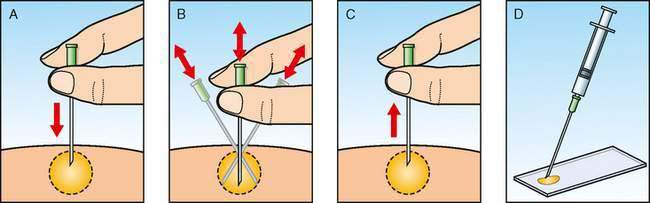

An alternative method of aspiration biopsy uses no suction but relies on capillary action to draw cells into the needle. This technique (Fig. 4-1) is preferred for lymphoid organs to prevent excess blood contamination.

When preparing impression smears from an excisional biopsy, it is important to blot excessive tissue fluids before touch preparations are made to increase the cellular yield. The cut surface of the excised lymph node is blotted on a paper towel, and then touched gently to a glass slide. To avoid the formalin artifact cytologic and histopathologic samples must be mailed separately when submitted to a referral laboratory.

Normal Histology and Cytology

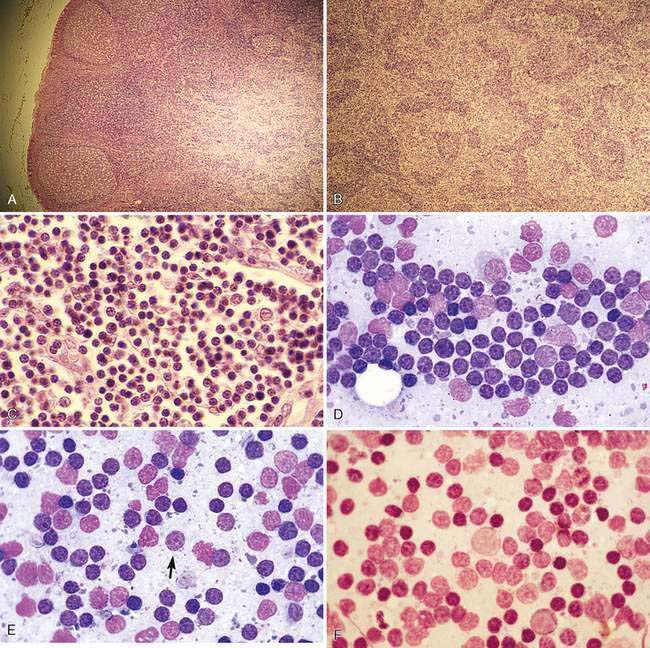

The canine or feline lymph node consists of a thin connective tissue capsule that surrounds cortical and medullary lymphoid tissue and extends inward as trabeculae. The outer cortex contains variably sized lymphatic nodules (Fig. 4-2A) composed primarily of B-lymphocytes surrounded by a thin rim of small T-lymphocytes. The diffuse lymphoid tissue between the nodules composed primarily of T-lymphocytes extends deep into the paracortex, where macrophages and dendritic reticular cells act as antigen-presenting cells. The diffuse lymphoid tissue extends inward to form medullary cords (Fig. 4-2B), which contain B-lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and other leukocytes. Between the cords are endothelial-lined sinuses in contact with dendritic reticular cells and reticular fibers. Lymph enters the afferent vessels that penetrate the capsule, through the subcapsular and cortical sinuses of the cortex, into the medullary sinuses and exits through efferent vessels at the hilus. Blood flow enters the hilus through arterioles that branch into the cortex to perfuse the lymphatic nodules. In this region, vessels enlarge to form postcapillary or high endothelial venules of the paracortex (Fig. 4-2C). These venules are important sites for the travel of lymphocytes from blood into the lymph node parenchyma that is related to the selective binding of the lymphocyte with receptors on the endothelial cells. The venules drain into larger veins that exit via the hilus region.

Cytologically, small, well-differentiated lymphocytes that measure 1 to 1.5 times the diameter of an erythrocyte in the dog and cat compose approximately 90% of the population (Fig. 4-2D). The chromatin of these cells is densely clumped with no visible nucleoli. Cytoplasm is scant. These cells are the darkest staining of all the lymphocytes. The medium and large lymphocytes whose nuclei measure two to three times erythrocyte diameter may be present in low numbers (<5% to 10%) (Fig. 4-2E&F). Their nuclei have a fine, diffuse, and light chromatin pattern. Nucleoli may be prominent. The cytoplasm is more abundant and often basophilic. Mature plasma cells represent a small portion of the cells found. Their chromatin is densely clumped and often the nucleus is eccentrically placed within the abundant, deeply basophilic cytoplasm. A pale area or halo is seen adjacent to the nucleus, which indicates the Golgi zone. Occasional macrophages (histiocytes) appear as large mononuclear cells with abundant light cytoplasm, often containing cellular debris. Nuclear chromatin is finely stippled and nucleoli may be found in activated macrophages. Mast cells and neutrophils also may be present in low numbers (Bookbinder et al., 1992).

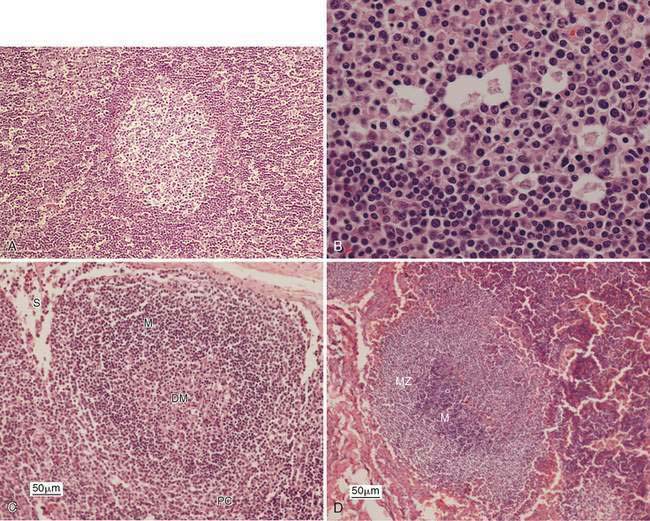

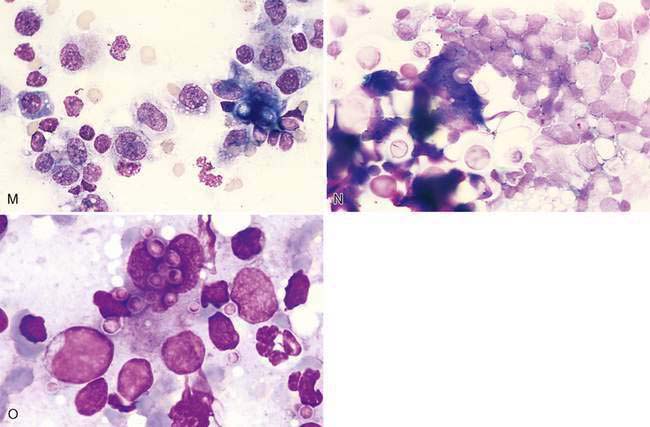

Reactive or Hyperplastic Lymph Node

Enlargement of a lymph node under this condition is due to any local or generalized antigenic response, which may include infection, inflammation, immune-mediated disease, or neoplasia from an area that drains into the lymph node. Histologically, lymphoid nodules within the cortex form prominent germinal centers that develop following antigen stimulation (Fig. 4-3A). A light and dark zone compose the germinal center. In addition to small lymphocytes, the center light zone contains reticular dendritic follicular cells, macrophages, and larger lymphoid cells (Fig. 4-3B). In benign hyperplasia, the dark zone or mantle cell cuff expands from proliferation of small B-lymphocytes that surround the pale portion of the germinal center with the thickest portion of the cuff at the apical end (see Fig. 4-3B). The hyperplastic germinal centers often demonstrate polarity (Fig. 4-3C) directed towards the antigen source, so that a dark mantle cell cuff is at one end (cortical) and a more pale group of large lymphocytes appears at the other end (medullary). The presence of follicular polarity helps distinguish follicular hyperplasia from follicular lymphoma (Valli, 2007). In contrast to the heterogeneity of the germinal centers, the nodules in follicular lymphoma contain a monomorphic population of neoplastic lymphocytes. The expanded follicles may press against the capsule, producing a thin mantle zone, but there is no destruction of the subcapsular sinus as occurs with lymphoma. With expanded hyperplasia, marginal zone cells that surround the mantle cell cuff may increase in number producing a heterogeneous population that expands into the paracortical region and mixes with resident T-lymphocytes (Fig. 4-3D). Sampling these areas cytologically displays cell size variability without a marked increase in plasma cells. The marginal zone cells are unique in their appearance with a medium cell size (nucleus about 1.5 times the erythrocyte diameter) and abundant cytoplasm contributing to the lighter color on histopathology. Marginal zone cells may be transformed to have marginated chromatin and contain a single large, centrally located nucleolus, but mitotic activity is low despite the immaturity of these cells (Fig. 4-3E). Specialized paracortical blood vessels termed high endothelial venules in view of their cuboidal or rounded nucleus increase in prominence and number. The T-lymphocytes from circulating blood enter the paracortex transmurally through these venules. Retention of these venules between follicles helps distinguish histologically paracortical hyperplasia from lymphoma in which they may be incorporated within the nodular or follicle-like neoplasia. In response to antigenic stimulation, plasma cells move from the paracortex and accumulate within the medullary cords (Fig. 4-3F&G), where they produce antibodies.

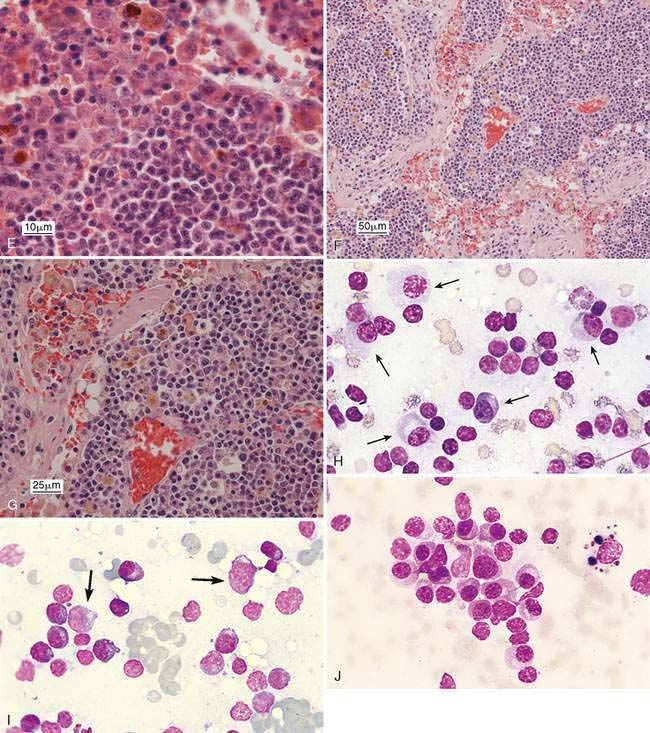

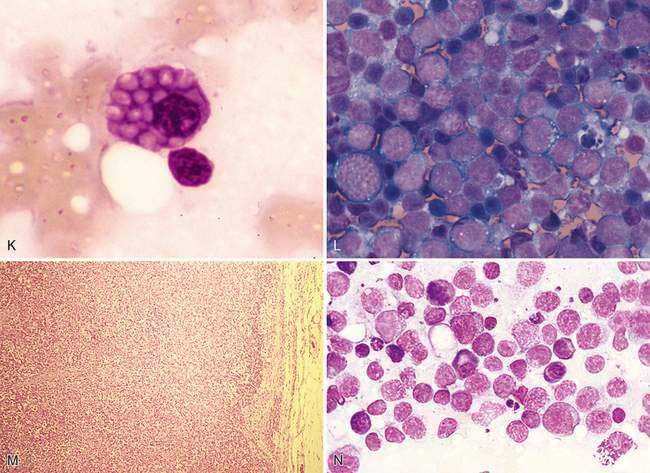

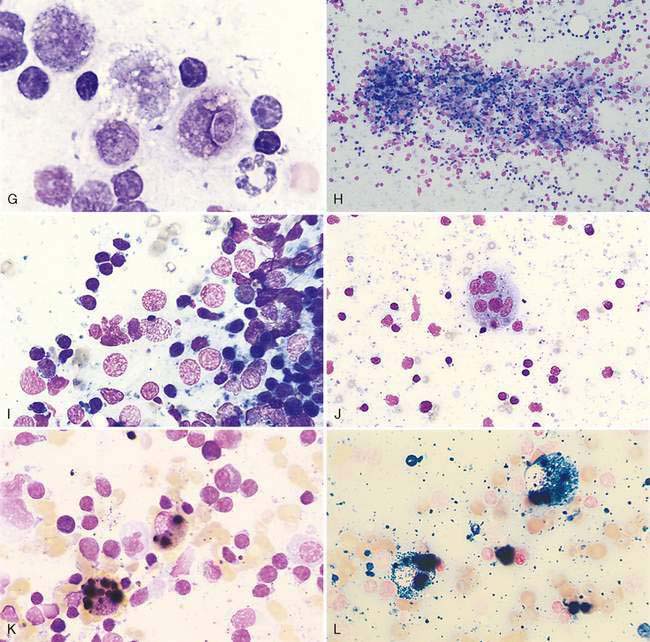

Cytologically, small lymphocytes predominate in reactive or hyperplastic lymph nodes, but there is an increase (>15%) in medium and/or large cell types of the total cell population (Fig. 4-3H). Plasma cells are mildly to markedly increased in number and may be shifted toward immaturity (Fig. 4-3I&J). Some highly activated plasma cells, termed Mott cells, are characterized by abundant cytoplasm filled with multiple large, spherical, pale vacuoles that represent immunoglobulin secretions known as Russell bodies (Fig. 4-3K). Macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells also may mildly increase in response to antigen stimulation; however, these cells occur in lower numbers than expected for lymphadenitis.

During early antigenic stimulation before germinal centers have developed, the paracortex responds with expansion and crowding of the cortex (Fig. 4-3L). Paracortical hyperplasia may precede plasma cell proliferation, and two weeks may pass before the appearance of prominent germinal centers. During this time, aspirate smears may contain a variably sized lymphoid population without significant numbers of plasma cells.

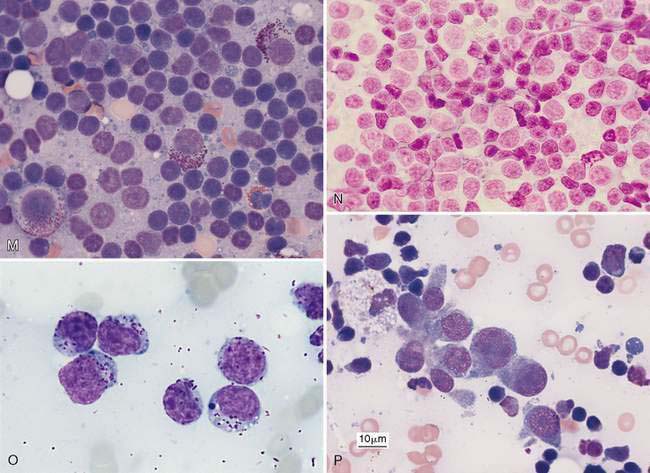

A benign condition in young cats has been reported (Moore et al., 1986; Mooney et al., 1987) in which peripheral lymph nodes show marked enlargement that histologically resembles lymphoma (Fig. 4-3M). Cells may be primarily medium and large lymphocytes with low numbers of small lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 4-3N). High endothelial venules are prominent in the paracortex in this condition (Valli, 2007). These cases generally regress spontaneously in 1 to 17 weeks (Mooney et al., 1987). In one study, the majority of cats were feline leukemia virus (FeLV) positive and 1 of 14 cats progressed to lymphoma (Moore et al., 1986). Generalized lymphadenopathy is known to occur in cats infected with feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and Bartonella sp. (Kordick et al., 1999).

Immunostaining of reactive lymph nodes demonstrates the paracortical expansion of T-lymphocytes (Fig. 4-3O) and the development of the germinal centers (Fig. 4-3P&Q).

Lymphadenitis

The predominant inflammatory cell population categorizes the type of inflammation in a lymph node.

Neutrophilic Lymphadenitis

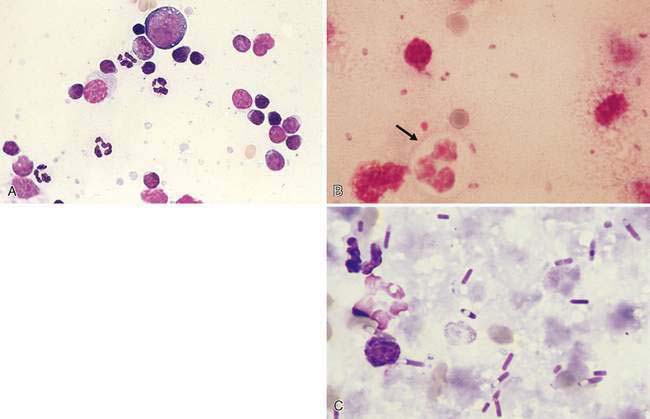

Purulent or suppurative (Fig. 4-4A) lymphadenitis involves greater than 5% neutrophils and may be associated with bacterial (Fig. 4-4B&C), neoplastic, or immune-mediated conditions.

Eosinophilic Lymphadenitis

Greater than 3% eosinophils of the nucleated cell population are often related to flea bite hypersensitivity, feline eosinophilic skin disease (Fig. 4-5A), hypereosinophilic syndrome, and paraneoplastic syndrome for mast cell tumor (Fig. 4-5B), as well as certain lymphomas (Thorn and Aubert, 1999) and carcinomas (Fig. 4-5C).

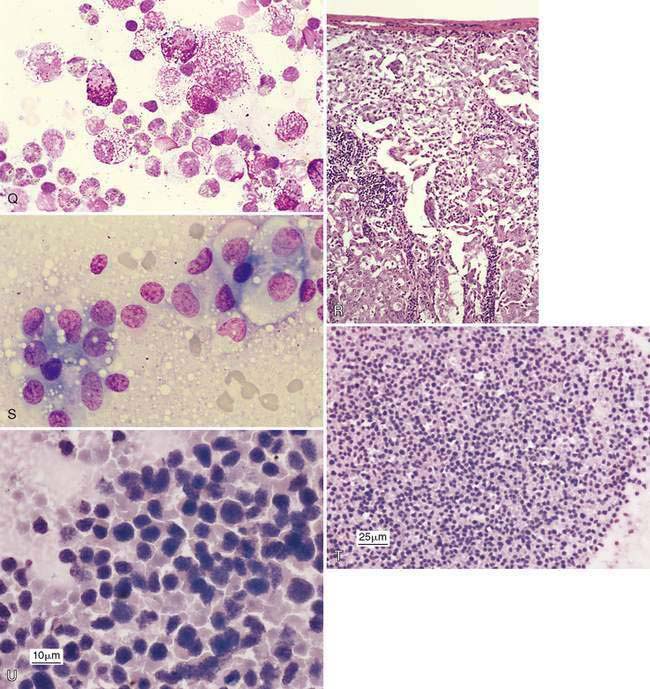

Histiocytic or Pyogranulomatous Lymphadenitis

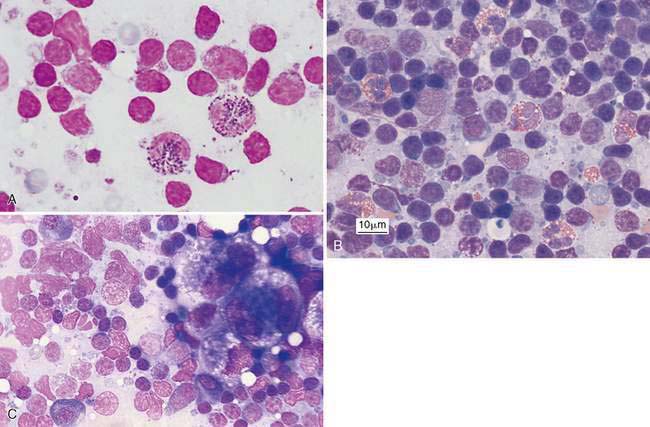

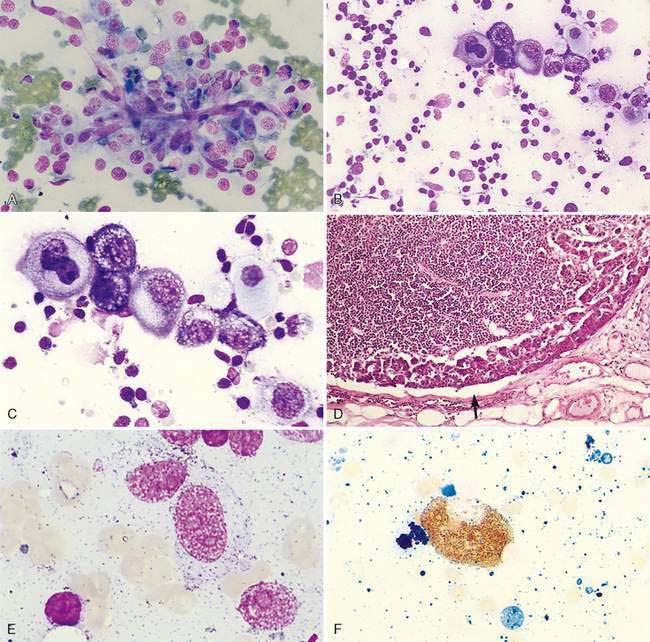

Inflammation of the lymph nodes may involve increased numbers of macrophages, which is termed histiocytic lymphadenitis (Fig. 4-6A), or involve a mixture of neutrophils and macrophages, referred to pyogranulomatous lymphadenitis (Fig. 4-6B), even though a granuloma is best appreciated on histologic sections. Conditions associated with these inflammatory responses include systemic fungal infections, other fungal infections (Walton et al., 1994) (Fig. 4-6C), mycobacteriosis (Grooters et al., 1995), leishmaniasis, salmon fluke poisoning disease (Fig. 4-6D&E), protothecosis (Fig. 4-6F&G), pythiosis, vasculitis (Fig. 4-6H-J), and hemosiderosis (Fig. 4-6K&L) (see Fig. 4-3G). The systemic fungal diseases include blastomycosis (Fig. 4-6M), cryptococcosis (Lichtensteiger and Hilf, 1994) (Fig. 4-6N), histoplasmosis (Fig. 4-6O), and coccidioidomycosis.

Metastasis to the Lymph Node

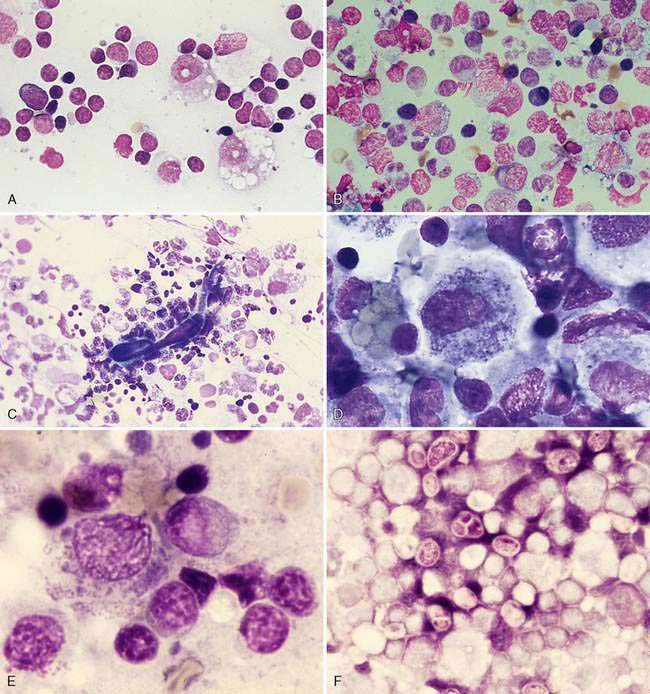

Metastasis is suggested by the presence of a cell population not normally expected in a lymph node, which for epithelial cells is relatively easier to detect because of their large cell size and clustered appearance (Fig. 4-7A&B). These foreign cells often appear larger than surrounding lymphocytes and abnormal, displaying several cytologic features of malignancy (Fig. 4-7C). Histologically, metastasis to the lymph node may occur at the peripheral sinus or medullary sinuses related to lymphatic spread (Fig. 4-7D).

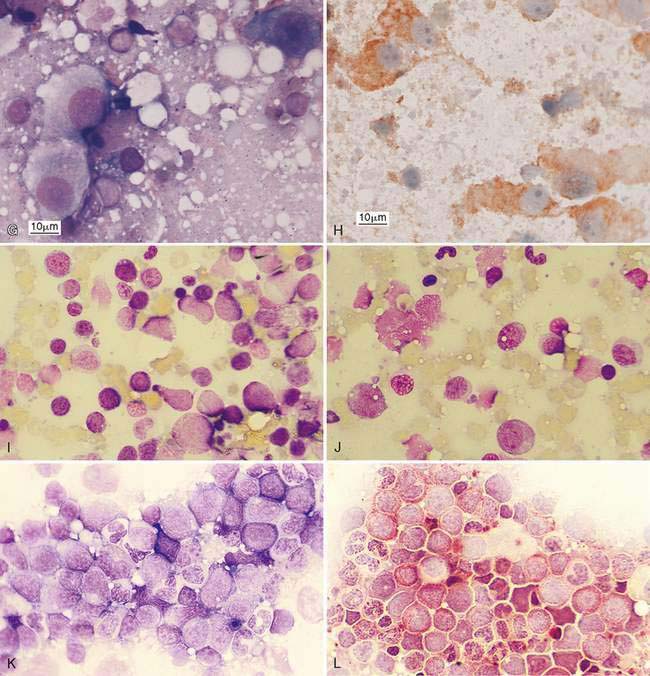

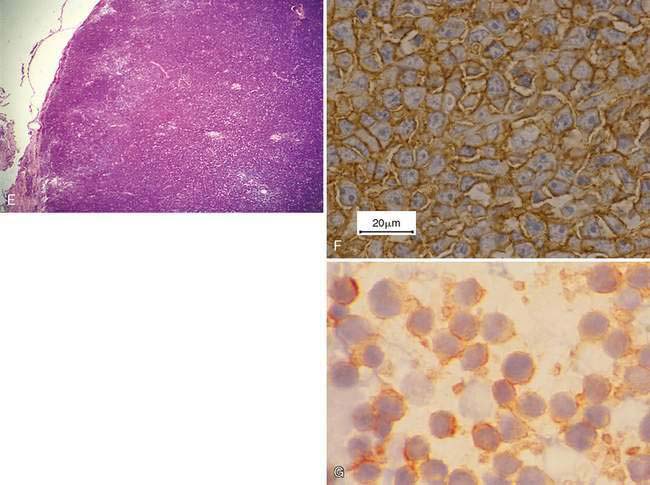

Mesenchymal-appearing neoplasms are most difficult to recognize because of their individualized cell presentation. The presence of anaplastic round to spindle-shaped cells in a lymph node aspirate can support a diagnosis of malignancy (Desnoyers and St-Germain, 1994). Tumors such as melanoma may be easily confused with hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Grindem, 1994) (see Fig. 4-6K) related to the dark blue-black granules. Hemosiderin granules tend to be variable in size, large, and coarse compared with melanin granules that are small and finely granular (Fig. 4-7E). Cytochemical staining may be necessary to distinguish the two, such as Fontana stain for melanin and Prussian blue for iron (Fig. 4-7F). Furthermore, immunochemistry may be helpful in amelanotic cases that lack visible granules (Fig. 4-7G) using markers such as S-100, Melan-A (Fig. 4-7H), and others (see Chapter 17).

Metastatic hematopoietic neoplasms such as granulocytic leukemia cause mild to moderate lymphadenomegaly. The cell population appears mixed (Fig. 4-7I) and dysplastic cells or granulated precursors may be present (Fig. 4-7J). In some cases myeloblasts may be indistinguishable from lymphoid precursors (Fig. 4-7K) and cytochemical staining for granulocytic origin may be indicated (Fig. 4-7L). Well-granulated mast cells may appear in low numbers, up to 6 per slide in clinically healthy dogs (Bookbinder et al., 1992), but increased cell numbers and the appearance of poorly granulated mast cells suggest metastasis (Fig. 4-7M&N). The presence of eosinophils, especially in the dog, suggests degranulation and release of histamine. Lymphoid malignancies originating from the bone marrow or solid tissue sites such as the spleen or gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 4-7O) may be easily recognized in lymph nodes when cells are granulated (Goldman and Grindem, 1997). The immunophenotypic features of feline large granular lymphocytes (LGL) are similar to the small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and hence may be the site of origin of this lymphoma in cats. In dogs, by contrast, the spleen is the site of origin (Roccabianca et al., 2006). The prognosis is poor for cats with LGL lymphoma, with median survival in treated animals of 57 days (Krick et al., 2008). Metastases from sarcomas are often difficult to discern among the normal fibrohistiocytic elements. However, angiosarcomas have distinctive, large, individualized cells that may be prominent against the small lymphocytes (Fig. 4-7P).

Inflammation may accompany metastasis to lymphoid tissue, with eosinophils most commonly present as a paraneoplastic syndrome in canine mast cell tumors (Fig. 4-7Q) or some carcinomas (see Fig. 4-5C). Neutrophils commonly occur with squamous cell carcinoma and may involve bacterial sepsis. The remaining lymphoid population often appears immune stimulated, with cell types present as described under Reactive or Hyperplastic Lymph Node. Early in the disease process, metastatic lesions will usually involve a small proportion of the entire cell population, usually less than 50%. In some cases, often late in the disease, the metastatic neoplasm may replace the lymph node parenchyma completely so as to interfere with the cytologic recognition of the tissue as lymph node (Fig. 4-7R-U).

Primary Neoplasia

These tumors originate from the lymph node and usually involve the lymphocyte population; rarely vascular tumors arising from the lymph node have been reported. Hogen-Esch and Hahn (1998) described eight hemangiomas and one lymphangioma, mostly in the popliteal lymph node of aged dogs from a research colony, which were found as incidental lesions at postmortem.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma is a very common spontaneous neoplasm in dogs and cats. One study found an incidence of 103 cases within a pet population of 130,684 insured dogs in the United Kingdom (Edwards et al., 2003). Within this population boxers had significantly higher relative risks compared with other breeds. The other breeds with increased relative risk included basset hound, St. Bernard, Scottish terrier, Airedale terrier, bulldog, Labrador retriever, Bouvier des Flandres, and Rottweiler (Edwards et al., 2003). Others with observed increased risk include Golden retrievers and bull mastiffs.

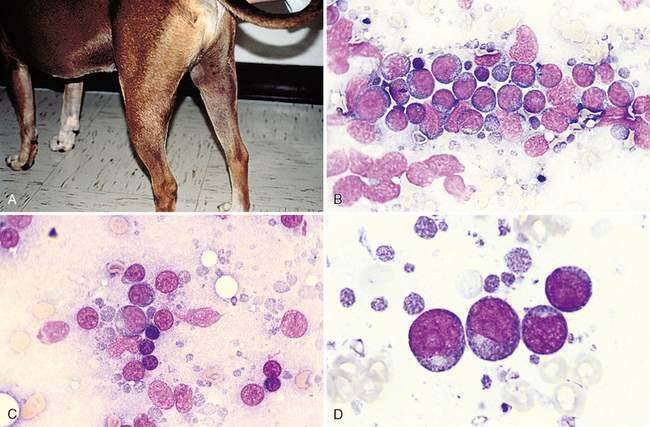

Primary neoplasia most often involves the lymphocytes of the lymph node and is termed lymphoma (formerly termed lymphosarcoma). It is generally recognized as lymphadenomegaly (Fig. 4-8A). The predominant neoplastic cell in dogs and cats is usually a medium or large immature lymphocyte; however, the cat may display a small cell lymphoma within the alimentary tract (Twomey and Alleman, 2005). Medium-sized or large lymphocytes often compose >50% of the total cells in lymphoma (Fig. 4-8B). An exception is the infrequent presentation of a T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma in which reactive T lymphocytes represent the majority of the cell population. A report by Steele et al. (1997) demonstrated by using immunohistochemistry that a parotid mass in a cat contained low numbers of large, atypical B-cells among many small reactive T-lymphocytes.

A micrometer such as an erythrocyte is used to determine the size of the lymphocytes present (Fig. 4-8C). The nucleus of a small, medium, and large canine lymphocyte is 1 to 1.5, 2 to 2.5, and > 3 times a red blood cell (RBC) diameter, respectively (Box 4-1).

BOX 4-1 Cytologic Protocol and Terms Used to Evaluate Lymphoma Cases

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree