Chapter 28 Laparoscopy

Instrumentation

Equipment

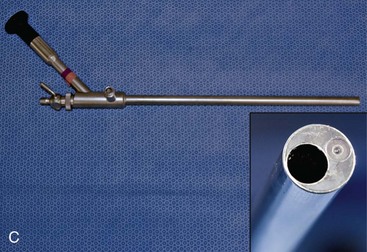

Size and viewing angles of laparoscopes vary, some of which are depicted in Figure 28-1. Small-diameter scopes (2.7 to 5.0 mm) have a smaller image with a narrower field of view. Light sources with greater intensity and video cameras with greater light sensitivity are needed with smaller scopes. Scopes up to 10-mm diameter can be used, and although these generate a bigger and brighter image than 5-mm–diameter scopes, this advantage applies only to very large dogs. Scopes are also available in various degrees of angulation of view, from 0° (direct forward viewing) to 70° angle viewing. The 0° angle view has the field of view centered on the long axis of the scope, and thus is easier to use and generally preferred for most procedures. A 30° angle scope can be used to view structures to the side of the tip, and through rotation can be used to expand the field of view. Angled scopes are more difficult for inexperienced operators with regard to spatial orientation, and they pose greater difficulty when using instruments through a second or accessory puncture site. The technique of triangulation to find the tip of the instrument is particularly more difficult with an angled field of view. Taking all these factors into account, a forward-viewing (0°), 5-mm outer diameter, 35-cm long scope is preferred for most dogs and cats. As most laparoscopic instruments are 5 mm in diameter, this provides more versatility by allowing the scope and instruments to be interchangeable with the same cannula. The operator must ensure the scope fits properly through the selected cannula, that the light cable has the appropriate connection to the telescope, and that the video camera fits properly onto the eyepiece.

Most scopes have no biopsy channel. Operating scopes have a 5- to 6-mm channel, with an eyepiece extending from the proximal end (see Fig. 28-1C). These scopes allow introduction of instruments through the same puncture site as the scope. This has the advantages of reducing the number of puncture sites and facilitating identification of the instrument tip for inexperienced operators. The major disadvantage of operating scopes is the limited ability to manipulate instruments passing through the channel. An accessory or secondary puncture technique is usually preferred by more experienced laparoscopists (see “Accessory Puncture Sites” section).

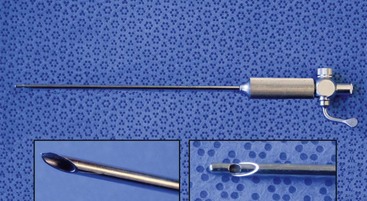

To visualize abdominal structures, a pneumoperitoneum must be created to lift the abdominal wall away from the viscera. This is accomplished by insufflating gas through tubing attached to a Veress needle (Fig. 28-2). The Veress needle has a spring-loaded blunt inner portion and an outer cannula with a sharp point. The sharp point is used to penetrate the abdominal wall. The inner blunt portion is then protruded past the sharp point and is maintained in that position to avoid traumatizing abdominal organs. Gas can be continually insufflated as needed throughout the procedure. Carbon dioxide gas (CO2) is recommended because it has the advantage of being rapidly absorbed, thereby minimizing the risk of air embolism. Air embolism is a complication that is more likely to take place if using room air. The disadvantage of CO2 is that it is slightly more irritating to the peritoneal surface and therefore requires a slightly greater depth of anesthesia. The pneumoperitoneum is maintained throughout the procedure with an automatic insufflator, which continuously administers gas to maintain pressure. Insufflators regulate both flow rate and intraabdominal pressure. Initial gas insufflation should be at a low flow rate (e.g., 1 L/min) to permit accommodation to the increasing intraabdominal pressure. If the pressure suddenly rises during insufflation, it is often a result of omental or mesenteric obstruction, or the incorrect placement of the needle. The position of the needle should be adjusted by gently moving it in and out of the abdomen; occasionally it must be replaced completely. Once optimal insufflation has been achieved, a higher flow rate can be used to maintain desired pressures. Ideally, intraabdominal pressure should not exceed 10 mm Hg (cats and small dogs) to 15 mm Hg (large dogs). Excessive pressure decreases central venous return and reduces diaphragm movement, causing decreased ability to ventilate. These effects are unlikely to occur at recommended abdominal pressures, but should be considered in patients with preexisting cardiopulmonary disease.

After the creation of the pneumoperitoneum, the laparoscope is introduced into the abdomen with the use of a trocar/cannula assembly (Fig. 28-3). The cannula is a metal or hard plastic sleeve with a one-way valve that permits passage of instruments (such as the trocar, laparoscope, and accessory instruments) and prevents the escape of gas. The trocar is a sharp-pointed stylet that is used to penetrate the abdominal wall. Once the trocar/cannula assembly penetrates the body wall, the trocar is then removed, leaving the cannula in place for introduction of the laparoscope.

Figure 28-3 A, Trocar/cannula assembly with threaded shaft. B, Telescope inserted through cannula with smooth shaft.

Accessory Puncture Sites

Accessory puncture sites are made for introduction of additional trocar/cannula assemblies. Accessory puncture sites permit the introduction of a variety of palpation, biopsy, and surgical instruments. These instruments are elongated, narrower versions of standard surgical instruments. A “basic” laparoscopic accessory pack should consist of a blunt metal probe, “spoon” or “clamshell” style (oval cup) biopsy forceps, grasping forceps, scissors, suction device, cautery instrument, and Babcock forceps (Fig. 28-4). An “advanced” laparoscopic accessory pack should also include retractors, reticulating instruments (which allow the tips to bend or be deflected), clip applicators, suturing devices, advanced hemostasis devices such as the Harmonic scalpel (Ethicon) and the LigaSure device (Covidien), and stapling equipment. The use of stapling equipment permits additional procedures such as vessel ligation and bowel resection.

Indications and Contraindications for Laparoscopy

Common indications for laparoscopy are for the evaluation of hepatobiliary disease. Laparoscopy allows procurement of large specimens (similar in size to surgical biopsies) using a 5-mm “spoon” or “clamshell” forceps (see Fig. 28-4). Samples obtained with these instruments have a superior diagnostic yield compared with needle biopsies, which have a reported 50% concordance with histologic findings from surgical biopsies.1 Furthermore, the ability to visualize the liver gives the clinician a better feel for the pathologic process present and its distribution. Laparoscopy can also be used to examine and biopsy the right limb of the pancreas, an organ that can be difficult to image with abdominal radiographs and ultrasound. Other organs that can be biopsied via laparoscopy include the kidney, spleen, prostate, intestine, mesentery, omentum, and parietal peritoneum. Laparoscopy can be used to diagnose and stage abdominal tumors through direct visual assessment and biopsy. Laparoscopy can detect lesions less than 1 mm in diameter on the surface of organs. It can guide the aspiration of gallbladder, loculated ascites, and abdominal cysts or abscesses. Laparoscopy can guide transabdominal intrauterine artificial insemination. Laparoscopy can also be used for the evaluation of abdominal trauma. Injuries such as hepatic or splenic laceration, diaphragmatic hernia, bladder rupture, renal rupture, and abdominal hernia can be readily identified. There are also a variety of surgical or interventional procedures that can be accomplished laparoscopically.

General Laparoscopic Technique

Several skills are required to perform a successful laparoscopic procedure.2 The operator must have a good grasp of abdominal anatomy, surgical principles, anesthetic induction and maintenance, and operative use of laparoscopic equipment. Compared with surgery, laparoscopy poses three additional challenges—two-dimensional imaging, lack of tactile sensation, and problems with depth perception—all of which pose significant challenges for the inexperienced laparoscopist. The operator must be familiar with the general feel of the instruments, and how slight movements of the camera head can result in wide excursions of the image. Tactile sensation can be developed with practice through the use of a blunt probe. Fluctuant structures can usually be distinguished from solid structures using the blunt probe. There is also a fulcrum sensation that occurs with instrument movement. Because the instruments and scope are entering the abdominal cavity through a cannula, movement of the tip is in a direction opposite to that of the handle. Thus, when the hand and handle are moved upward, the tip of the instrument moves downward. When the hand and handle are moved to the left, the tip of the instrument moves to the right. Another necessary skill necessary is triangulation, because the angle of the scope and the angle of the instrument form a triangle. Triangulation permits the operator to find an instrument placed through a secondary or accessory cannula in the field of the scope. The angle of entry of each component of the triangle must be recognized to avoid frustration when attempting to find the instrument tip. One technique that is helpful is to move the scope further away from the anticipated point of the instrument tip. This will increase the field of view. Once the tip of the instrument is located, the scope can be moved closer to the instrument to improve visualization. At this point the instrument and scope are moved in parallel so that the instrument tip never leaves the field of view. This technique will reduce unnecessary anesthesia time. The skill of triangulation becomes more challenging when using an angled scope (such as a 30° telescope). If the viewing angle is directed upward and an instrument is inserted from the side, it appears to come from below and to the side of the field of view.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree