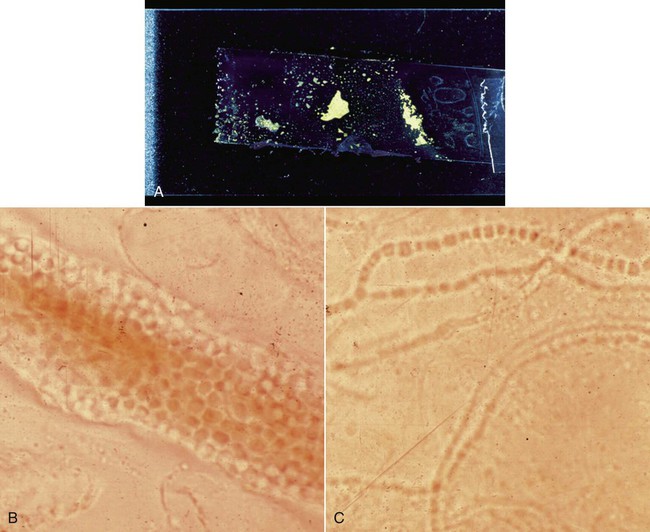

Specific diagnosis of fungal and algal infections in animals requires laboratory procedures that include direct microscopic examination and culture, frequently supported by serologic tests. Many such direct examinations and primary cultures and some serologic tests are now well within the scope of point-of-care diagnostic procedures for veterinary practice. The development of improved methods for mycologic diagnosis is directed at rapid procedures using prepackaged identification kits and reagents, serologic kits, automated systems, and molecular techniques.20 In a high proportion of such cases, confirmation by a specialty laboratory will still be necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. Refer to Web Appendix 5, Laboratory Testing for Infectious Diseases of Dogs and Cats. A satisfactory sample should be representative of the focus of infection and of adequate size to permit direct examination and culture. Except in systemic infections suggesting fungemia and requiring blood culture, samples should be obtained from an active site of infection as indicated by lesions, signs, or symptoms. Because systemic mycoses are usually acquired via the respiratory tract, lung tissue or airway exudates are preferred samples. In certain disseminated mycotic infections, urine and bone marrow may also be an appropriate specimen to culture. Cultures taken from the respiratory tract, draining tract, nasal sinus, abscess, corneal, biopsies, indwelling catheters, hair, and nails are examples of nonsystemic specimens.16 Swabs are of limited value in fungal isolation, and their use is discouraged. If no alternative collection method is available, specimens received on swabs in a suitable transport medium (see Chapter 29) should be cultured without delay. Swabs for direct smears preferably should not consist of cotton because recovery rates are poor, and inexperienced observers may mistake cotton fibers for hyphae. Blood for cultures is collected directly via syringe and needle into conventional and biphasic blood culture bottles, automated blood systems, and lysis-centrifugation systems (see Isolation).1,13,13 A fresh needle is used for transfer of blood, 1 mL per 9 mL of culture medium, from syringe to the culture bottle. Blood samples taken from indwelling intravenous catheters are not recommended.1,13 Urine is best taken by percutaneous cystocentesis, which ensures a sample uncontaminated by bacterial or fungal flora in the lower genitourinary tract (see Chapter 90). Stool specimen cultures for diagnosis of fungal infections of the gastrointestinal tract are generally misleading. Biopsy specimens for histologic examination are best. Fluids and contents of abscesses are collected through aspiration by needle and syringe. Large volumes, adequate for centrifugation, are best. Any granules should be included and characterized. Bone marrow is similarly sampled by needle and syringe or core needle biopsy. At least 3 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is desirable via lumbar or cisternal puncture. For lung sampling, a transtracheal or bronchial wash or bronchial brushing is done (see Chapter 87). Necrotic material or curettings and other surgically collected material should be handled aseptically pending examination and culture. Corneal lesions are sampled by scraping several times with a sterile Iris spatula sterling (Jarit, Hawthorne, NY), a surgical blade, or a nylon brush (see Fig. 92-14). Slide preparation and culture are done at the site and time of collection. Specimens should be transported at room temperature and processed as soon as possible or within 2 hours. Specimens that cannot be promptly processed can be held up to 24 hours in a suitable bacterial transport medium either at room temperature or at 4° C if bacterial contamination is likely (see Chapter 29.)15 Refrigeration may delay proliferation of slow-growing fungi for 1 to 2 days. Aspergillus and zygomycetes are sensitive to refrigeration. If a specimen suspected of harboring a zygomycete cannot be promptly cultured, overnight storage at room temperature in a bacteriologic transport medium is permissible. Some fungi have been recovered from specimens up to 2 weeks in transit, but this type of delay is not recommended because of the likelihood of bacterial contamination. Blood culture bottles or lysis-centrifugation tubes (see Isolation), if subject to delay in processing, can be held at room temperature for up to 16 hours. CSF and fluids from serous cavities and joints should be processed as soon as possible. The presence of proteins and carbohydrates in CSF contributes to its qualities as a maintenance medium. CSF should be held at room temperature if not cultured immediately. Sterile fluids should be held overnight under refrigeration. Nasal curettings and excised polyps may be divided between sterile containers for culturing and jars of 10% buffered formalin for histologic preparation aimed at diagnosing rhinosporidiosis (Fig. 54-1). Impression or scrape smears of nasal tissue should be made before fixation of specimens (see Fig. 68-3). Tissue and bone marrow may be moistened with a small amount of sterile saline if transport is delayed. The search for diagnostically significant fungal structures may involve preparation of stained or unstained wet mounts, fixed stained smears, and histologic sections. Some of these techniques are simple and rapid and may provide the clinician with a presumptive or even definitive diagnosis and a timesaving guide to therapy (Table 54-1). TABLE 54-1 Direct Examination of Fungi in Clinical Specimens The KOH digestion method is employed universally in preparation of cutaneous samples suspected of harboring dermatophytes (see Chapter 56). The hair or skin scraping to be examined is placed into a drop of 10% KOH on a clean slide (Fig. 54-2, A). Material may require soaking in KOH for a period before further processing. The crusty material is teased apart with forceps or dissecting needles, mounted on a clean glass slide, and covered with a coverslip. Gently press the coverslip down to expel any bubbles. This preparation is passed over an open flame several times, but care must be taken not to boil the mixture. This slide is examined immediately for the presence of arthroconidia or fungal chains embedded in the material (see Fig. 54-2, B and C). If no organisms are initially observed, the slide is reexamined in 30 minutes. A more sensitive modification of the KOH preparation contains chlorazol black E and DMSO (Delasco, Council Bluffs, IA) which stains the hyphae green against a gray background. A mixture of 20% KOH and 36% dimethyl sulfoxide or 25% KOH or sodium hydroxide (NaOH) with 5% glycerol increases penetration and clarity of specimens. Nails may require up to 2 hours for better clearing. India ink (Pelikan, Hannover, Germany) or nigrosin (1% aqueous), when mixed on a slide with fluids or exudates containing Cryptococcus spp., provides a dark background that outlines the large capsules surrounding the yeast cells (see Fig. 59-7, B). Placing a drop of test material and a drop of India ink separately on a slide and then adding a coverslip will allow for a proper mixture gradient to form. Less than 50% of culture-positive human CSF samples are proved to be detected by this method.1 Less generally available but useful methods of unstained wet mount study include phase microscopy, in which the visibility of fungal structures against a background of tissue debris is improved, and fluorescent microscopy, in which a specimen is prepared by mixing with an equal volume of 10% to 20% KOH and 0.5% calcofluor white (Difco, Detroit, MI) on a slide. The specimen is examined on a fluorescent microscope equipped with a 365-nm exciter filter and a barrier filter that will transmit light at 410 nm. The fungal wall will fluoresce brilliantly. This procedure would be available at commercial diagnostic laboratories. See Web Appendix 5.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Fungal and Algal Infections

Specimens for Laboratory Diagnosis

Sample Collection

Transportation and Preservation

Processing of Specimens

Direct Examination

Stain or Reagent

Usage

Text Figures/Disadvantages

Gram

Stains bacteria, yeasts, and other fungi

Cryptococcus neoformans (Fig. 54-3); Malassezia pachydermatis (Fig. 54-4); Sporothrix schenckii (Fig. 54-5); some fungi stain variably or not at all

Potassium hydroxide

Clearing tissue and cellular debris from variety of specimens to provide greater visibility of fungal elements

Dermatophytes (Fig. 54-2); artifacts develop after preparation time; experience required

India ink

Observation for presence or absence of capsules of fungal cells against a dark background

C. neoformans (Fig. 59-7, B); problems of artifacts can occur in the stain, poor sensitivity

Calcofluor white

A fluorescent brightener binding to polysaccharide such as cellulose and chitin

Detects variety of fungal elements; requires a fluorescent microscope

Wright

Stain for cytologic examination of peripheral blood, bone marrow, body fluids, and organ impressions

Histoplasma capsulatum (Fig. 58-8); Aspergillus (Fig. 62-4); Candida (Fig. 63-2, B); Prototheca (Fig. 67-3); limited use

Gomori’s methenamine silver

Detection of fungal elements in histologic section

Candida albicans (Fig. 63-3, B); not readily available to most clinical laboratories

Periodic acid–Schiff reaction

Detection of fungal elements in histologic section

C. albicans (Fig. 63-3, A); not readily available to most clinical laboratories

Hematoxylin and eosin

Routine histologic stain used for detection of some fungal elements

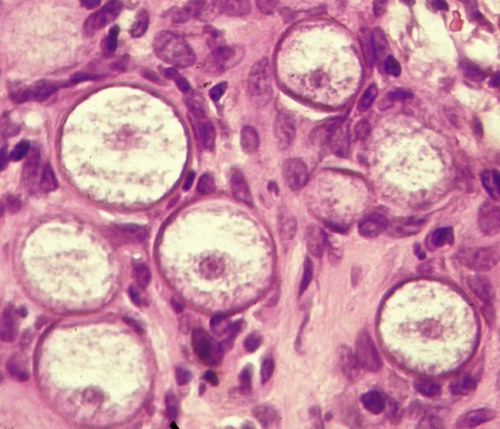

Rhinosporidium (Fig. 68-4); Coccidioides immitis (Fig. 60-8); Prototheca (Fig. 67-5); usually requires large numbers of fungi to be detected with this stain

Wet Mounts

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Laboratory Diagnosis of Fungal and Algal Infections