Integumentary and Dental Surgery

General Skin Wound Healing

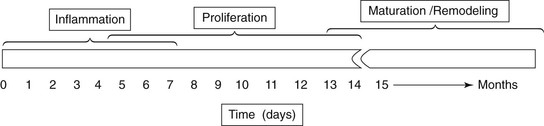

The skin provides a vital protective barrier to the body. Mechanisms to repair breeches of that barrier during wounding follow a predictable and efficient pattern in mammalian species. The process is often simplified to grasp the concept of the repair process, but in actuality, it involves a complex interaction of cells, fluid and protein constituents, and chemical mediators. The first general concept of wound healing is the phases of repair that include inflammation, followed by proliferation, and finally remodeling. It is important to first recognize that these phases involve significant time frame overlap during transition. In addition, each primary phase may be divided into subsets with unique mechanisms of repair. Primary surgical closure rapidly concentrates the healing process with more overlap between phases. Second-intention healing results in an exaggerated length of time to closure, depending on the size of the wound and the complications arising during the healing process.1

Managing Skin Wounds

After hemorrhage control, initial wound management should focus on controlling the inflammatory process, reducing edema, assisting with wound debridement, and treating infection. With regard to inflammation, the goal should be to modulate the inflammatory process and not block it entirely. The aim should be to control an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response while not suppressing neutrophil migration and function within the wound as a normal part of the healing process. Glucocorticoids have been shown to downregulate L-selectin binding necessary for migration of neutrophils from capillary endothelium, as well as delay necessary neutrophil apoptosis for macrophage phagocytosis and sequential functions in the healing process.2,3 Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may more effectively modulate inflammation without deleterious effects on cellular function.4 Edema within a wound may be treated with compression wraps, when possible, as well as with hydrotherapy to increase perfusion and debride the wound.

Physical debridement of the wound should be undertaken with initial assessment, noting clinical characteristics, severity, structures involved, and estimating the duration (Figure 63-1). Gentle scrubbing of the wound initially with antiseptics will remove large debris. If povidone iodine is used for scrub or lavage, it should be a very dilute solution (<0.5%), as “free” iodine in solution is the basis for antimicrobial activity. Wound lavage with dilute antiseptic solution may then be used. Lavaging fresh, moderately contaminated wounds with antiseptic solution pressed from a 35-mL syringe through an 18-gauge needle provides tissue-friendly, targeted, focal hydropressure and debridement.

Figure 63-1 Phases of wound healing and general time frame of each phase. Epithelialization, a division of proliferation, is seen histologically at wound edges within the first days of injury.

Infection should initially be treated empirically by utilizing broad-spectrum systemic antibiotics as well as topical antiseptic therapy. The wound should be reassessed frequently, and culture and sensitivity should guide antibiotic therapy when unresolved infection appears to be complicating the healing process (Figure 63-2 and 63-3). Intravenous (IV) regional antibiotic infusion is proposed by some in cases of distal limb wounds, in the belief that higher concentrations of drug could be achieved in the area of interest. However, the counter-argument would be that the antibiotics that are safe and legal to use in this manner, namely, β-lactams, have time above MIC dependent mechanisms of action, and are not concentration dependent.5 However, IV regional antibiotic perfusion should provide more rapid distribution of the dose within the area of concern.6 If this practice is followed, the tourniquet should remain in place for at least 30 minutes for effective distribution of antibiotic within tissue.

Figure 63-2 Degloving injury of the medial aspect of the antebrachium in a yearling male llama, approximately 21 days after injury.

Mastectomy

Diseases of the teat and udder in llamas and alpacas are not commonly recognized. Reports on these conditions are extremely limited compared with those in sheep, goats, and dairy cattle. However, these diseases are important and significant to llama and alpaca breeders because the consequences of poor mammary health may be perpetuated along family lines and complicate the successful rearing of thrifty crias. Mastitis may be a severe problem and is a cause of poor milk production and low weaning weights of crias. Problems of the teat and udder requiring surgery seem to be much less common. Udder amputation is perhaps the most common teat and udder surgery done in llamas and alpacas.7 Udder amputation is performed when the udder has been damaged beyond repair. The udder might be amputated after a long-term chronic mastitis that has left a nonsecretory fibrotic mass with or without abscesses within the udder. In these cases, the animal often suffers from chronic infection.

The two halves of the udder are distinctly separate from each other and are supplied by separate arteries, veins, and nerves.8 The main arterial blood supply to the udder is via the external pudendal artery, which courses through the inguinal ring after having originated from the pudendoepigastric trunk, which originates from the deep femoral artery, which originates from the external iliac artery, which originates from the abdominal aorta. The venous blood from the udder is drained by the external pudendal veins, the caudal superficial epigastric veins and the perineal veins. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves provide nerve supply to the cranial udder. The genitofemoral nerve provides nerve supply to the caudal udder.

Udder amputation must be done cautiously because of the risk of untoward effects of surgery in an animal in poor physical condition from chronic infection and because of the risk of profuse, uncontrolled hemorrhage during surgery.7,8 The patient may be anemic because of the chronic nature of the infectious process. Removing a mass of the udder may result in severe hemorrhage and the creation of a large soft tissue defect that may be difficult to close completely. The owner must, therefore, be made aware of these potentially serious consequences. Amputation of the udder should be performed with the llama or alpaca under general anesthesia and with the appropriate facility to perform cardiopulmonary monitoring and intervention. A blood donor animal should be available, or blood should be harvested prior to surgery in case of life-threatening hemorrhage. If possible, the animal should be positioned in dorsal recumbency. This facilitates working on both sides of the udder simultaneously during surgery. If dorsal recumbency is not possible, the animal will need to be rolled from one side to the other during surgery, and the appropriate preparations should be made.

Dental Surgery

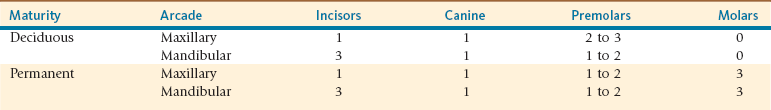

Dental disease is a common condition affecting llamas and alpacas. Problems affecting teeth are one of the most common presenting complaint of camelids presented to our practice. Camelids of all ages, both males and females, and those from different types of management conditions are represented. Dental problems include tooth root abscesses, mandibular osteomyelitis, malocclusion, tooth fractures, uneven teeth, tooth overgrowth, worn teeth, and retained deciduous teeth. Except for the fighting teeth in males, camelids have dentition designed for grinding of forages similar to other herbivores. They have incomplete rostral arcades with three lower incisors but only one upper incisor per side (Table 63-1). The premolars (PMs; PM1, PM2, etc.) and molars (Ms; M1, M2, etc.) are referred to as cheek teeth and are well established. Cheek teeth function to grind forages. The fourth premolar (PM4) is most always present but is smaller than the molars. The PM3 is frequently not seen in clinical and radiographic examinations. PM1 and PM2 are not present in llamas and alpacas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree