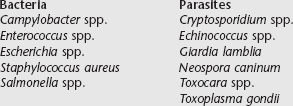

Chapter 264 In the United States there are approximately 78.2 million pet dogs and 39% of households own at least one dogs; there are approximately 86.4 million pet cats and 33% of households have at least one cat. In general it is estimated that at least 50% of households in the United States have at least one companion animal. In addition, it has been estimated that at least 10 million people, or 3.6% of the United States population, can be considered immunocompromised, defined as being positive for human immunodeficiency virus or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, being an organ transplant recipient, or being a cancer patient (Kahn, 2008). The number of immunocompromised people is even higher if those taking immunosuppressive drugs or those with suboptimal immune systems such as the elderly, pregnant women, infants, and children are included. It is estimated that 30% to 40% of immunocompromised people in the United States have at least one companion animal. It is highly recommended that immunocompromised people and households in which an immunocompromised person lives not feed raw diets to their companion animals (Kaplan et al, 2009). Many zoonotic bacteria and parasites potentially are associated with raw protein diets (Box 264-1). The purpose of this chapter is to provide the general practitioner with information concerning the most common agents associated with raw meat diets to use as a resource in helping educate clients who either are feeding or are considering feeding raw protein diets to their pets. It is important to note that there are many factors that affect microbial contamination of raw meat, including factors associated with the specific microbial contaminant, species of animal used to produce the product, degree of processing, number of times the product has been handled, facility where the product is produced, and sampling methods. Campylobacter spp. are gram-negative flagellated spirochetes that have been linked to numerous food-borne illnesses in humans. Although there are many serovars of Campylobacter, Campylobacter jejuni is most commonly implicated in food-borne illness. The internal body temperature of avians is ideal for this bacterium to live and proliferate, and so consumption of raw or undercooked poultry products appears to be the most common path of transmission. The CDC reports that in 2005 Campylobacter spp. was present on 47% of raw chicken breasts tested through the FDA-NARMS (National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System) Retail Food program. Some serovars of Campylobacter are pathogenic, and a small number of bacteria can be responsible for causing significant illness in humans. Animals consuming raw poultry are at risk of Campylobacter infection. One serotyping study showed that Campylobacter spp. isolated from dogs with diarrhea also were isolated from poultry carcasses the dogs had been fed (Remillard, 2005). Although some dogs and cats exposed to Campylobacter spp. develop gastrointestinal disease, others remain healthy but become colonized and shed the organism in their feces, thus serving as a source of potential human exposure. A common gram-positive commensal bacterium inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract of many animals is Enterococcus faecalis. It is a common contaminant of raw meat. A 2001-2002 study in Iowa of retail meat found 29% of samples to be contaminated with E. faecalis (Hayes et al, 2003). Although this bacterium seems to cause mostly incidental disease in companion animals, it is a bacterium that can exhibit extreme antibiotic resistance and is a growing concern for nosocomial infections in the humans. After ingesting the organism, animals can shed the resistant organism in their feces, contaminating the environment with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Escherichia spp. are facultative anaerobic gram-negative rod bacteria that populate the gastrointestinal tract of most species. These organisms are spread fecally and orally and can result in subclinical infection or significant gastrointestinal or systemic disease, including death, depending on both host and bacteria characteristics. Escherichia coli contamination is common in raw meat. In the 2010 Retail Meat Report presented by NARMS, of meat considered fit for human consumption, E. coli contamination rates were 67.6%, 83.1%, 43.2%, and 82.1% for ground beef, chicken breast, pork chop, and ground turkey samples, respectively (on average from 2002 to 2010). One veterinary study found 53% of commercially available raw meat diets consisting of beef, lamb, chicken, or turkey to be contaminated with non–type specific E. coli (Strohmeyer et al, 2006). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has emerged as a great concern for human medical doctors, and this “superbug” is beginning to become more of a problem in veterinary medicine. Although most people associate this organism with hospitals and shopping cart handles, a common source is raw meat. MRSA has been cultured from numerous raw meat samples that were sold for human consumption. For example, a study published in June 2011 found that 65 (22.5%) of 289 beef, chicken, and turkey samples from grocery stores in Detroit, Michigan, were positive for S. aureus on culture (Bhargava et al, 2011). Of these 65 positive samples, six were positive for MRSA. A similar study in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, that tested 120 raw pork and beef products from grocery stores found 45.6% of pork and 20% of beef samples to be contaminated with S. aureus. Of these samples, five pork and one beef sample were positive for MRSA (Shuaihua et al, 2009). Other studies worldwide show similar results. In these other studies, raw pork samples have shown the highest numbers of MRSA isolates on culture. S. aureus is different from other potential food-borne pathogens because it colonizes the skin, not the intestinal tract. Pyoderma and skin allergies are common illnesses of companion animals. The question has been raised, If a companion animal has an underlying skin disorder and is fed a raw diet contaminated with MRSA, is this animal more susceptible to developing a MRSA infection (from the environment or from licking or chewing itself)? More research needs to be done, but this could prove to be a significant human and animal issue. Salmonella spp. are gram-negative rod bacteria that are one of the most common pathogens associated with food-borne illness in humans and animals. Infected hosts with subclinical disease can be carriers and shed the bacteria in normal feces. Salmonella spp. enter through the digestive tract and can survive for weeks outside of the living body. It is estimated that at least 1% of human Salmonella infections in the United States are associated with contact with companion animals, and because the diagnosis of salmonellosis commonly is missed, this percentage may be much higher (Finley et al, 2006). As recently as the fourth quarter of 2011, the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service reported that 1.7% to 49.9% of poultry carcasses and ground poultry products intended for human consumption tested positive for Salmonella spp. According to the CDC approximately 0.05% of eggs (1 in 20,000) sold in the shell are contaminated with Salmonella spp. Although the percentage of Salmonella-infected eggs is small, it still amounts to approximately 2.3 million contaminated eggs per year. It also is estimated that approximately 2% of the beef sold in the United States for human consumption is contaminated with Salmonella spp. According to the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service fourth quarter report in 2011, 7.5% of ground beef samples tested positive for Salmonella spp. Information on food-borne disease in companion animals for the most part is lacking, but because Salmonella spp. are such common and potentially serious pathogens, there is considerable information pertaining to raw pet food contamination with this bacterium. For example, one study of commercially available raw meats for canines in the United States showed 5.9% to be contaminated with Salmonella enterica (Strohmeyer et al, 2006). In two studies of dogs fed raw meat diets in Canada, 3 of 10 dogs consuming a homemade diet and 5 of 7 dogs consuming a commercially available diet shed Salmonella spp. (Finley et al, 2006). Salmonella spp. have been implicated in disease and death in racing greyhounds, and one study found that 75% of 4D meat samples at one greyhound breeding facility and 93% of fecal samples from dogs at the same facility tested positive for Salmonella spp. (Morley et al, 2006). Finally, two cats in a single household died of salmonellosis that was linked to the raw meat diet being fed (Stiver et al, 2003).

Infectious Diseases Associated with Raw Meat Diets

Why Not Raw?

Infectious Organisms in Raw Meat

Bacteria

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree