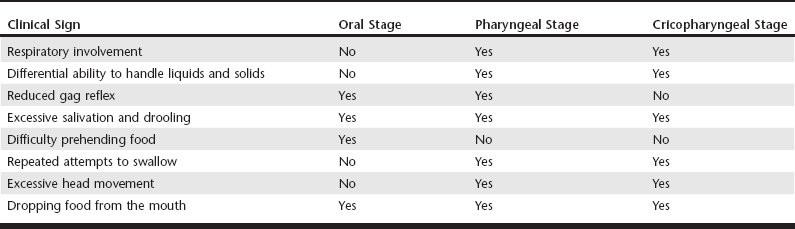

Web Chapter 54 Dysphagia, defined as an abnormality in swallowing, can be one of the most difficult diagnostic challenges encountered in clinical veterinary practice. Normal swallowing is a well-coordinated process involving the tongue, hard and soft palate, pharyngeal muscles, esophagus, and gastroesophageal junction. In addition to normally functioning striated muscle and neuromuscular transmission, the following are critical to the swallowing process: the integrity of several cranial nerves, including sensory and motor fibers of the trigeminal and facial nerves; the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and hypoglossal nerves; their nuclei in the brainstem; and the swallowing center in the brain reticular formation. Difficulties in swallowing may be found in very young animals associated with congenital abnormalities or as an acquired condition in mature animals. Swallowing is a complex process, and abnormalities of this process have been classified functionally based on cineradiographic analysis as the oropharyngeal, esophageal, and gastroesophageal dysphagias (Suter and Watrous, 1980; Watrous and Suter, 1983). Because of the complexity, the diagnosis of swallowing disorders should be approached in a systematic manner (see Chapter 121). As a clinical sign of oropharyngeal dysfunction, dysphagia is relatively common in dogs and less common in cats and can result from either morphologic or functional abnormalities. Structural changes that interfere with swallowing may include traumatic injury, strictures, foreign bodies, or neoplastic processes. Most functional abnormalities are caused by neurologic, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction, or primary muscle diseases. Dysphagia may be the sole presenting clinical sign or associated with multiple clinical abnormalities. A common misconception is that dysphagia is a specific disease. The term cricopharyngeal achalasia refers to a rare form of dysphagia characterized by inadequate relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle occurring in very young animals and surgically treated with a myotomy. Dysphagia also may be part of a generalized inherited myopathy in young dogs, such as a muscular dystrophy. It is most commonly an acquired condition in adult dogs with weakness of the pharyngeal muscles, resulting in inadequate propulsion of the bolus from the mouth into the proximal esophagus. In this context dysphagia is a clinical sign of disease and not a specific disease. Oropharyngeal dysphagia can be divided into three stages based on the site of dysfunction: the oral, pharyngeal, and cricopharyngeal stages. The oral stage is characterized by bolus accumulation at the base of the tongue. In oral dysphagia there is difficulty in prehending and transporting food to the oropharynx. Rostral-to-caudal pharyngeal constrictors act in concert with the plungerlike action of the tongue to propel the bolus from the base of the tongue to the cricopharyngeal passage in the second or pharyngeal stage. The inability to propel a bolus from the base of the tongue to the cricopharyngeal region is characteristic of pharyngeal dysphagia. The cricopharyngeal or third stage consists of relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscles (also referred to as the upper esophageal sphincter) and passage of the bolus into the cranial esophagus. Synchrony between constriction of the pharyngeal muscles and relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle allows the passage of a bolus into the esophagus. Failure of a normally propelled bolus to pass through the cricopharyngeal region is termed cricopharyngeal dysphagia. Clinical signs of the three stages of oropharyngeal dysphagia are described in Web Table 54-1. An accurate identification of a swallowing disorder is critical to reaching a specific diagnosis and devising a therapeutic plan. Visual examination of the oropharynx under tranquilization or general anesthesia may allow the identification of many of the morphologic abnormalities that cause oral dysphagia, including oral foreign bodies, dental disease, and neoplasia. Evaluation of cranial nerves should be performed, including assessment of tongue and jaw tone and abduction of the arytenoid cartilages with inspiration. Complete physical and neurologic examinations may identify clinical signs of a generalized neuromuscular disorder, including muscle atrophy, stiffness, or depressed or absent spinal reflexes (Glass and Kent, 2002). Acquired MG is the most commonly diagnosed neuromuscular disorder in the author’s laboratory and should be high on the list of differential diagnoses in dogs with a recent onset of dysphagia, whether alone or as part of a generalized neuromuscular disorder (Shelton, 2002). In a study of a large group of dogs with acquired MG (Shelton, Schule, and Kass, 1997), focal signs, including pharyngeal, esophageal, and laryngeal weakness without clinically detectable limb muscle weakness, were described in 43% of dogs. Pharyngeal weakness, as the only clinical sign of MG, was described in 1% of the myasthenic dogs. Similarly focal signs, including megaesophagus and dysphagia, were described in 14% of cats in a similar study (Shelton, Ho, and Kass, 2000).

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Functional Anatomy

Physical and Neurologic Examination

Diagnostic Testing

Neuromuscular Minimum Database

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree