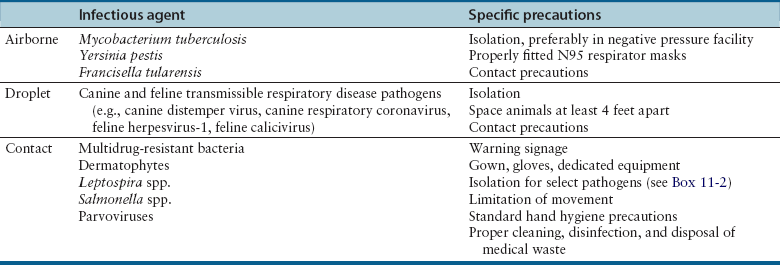

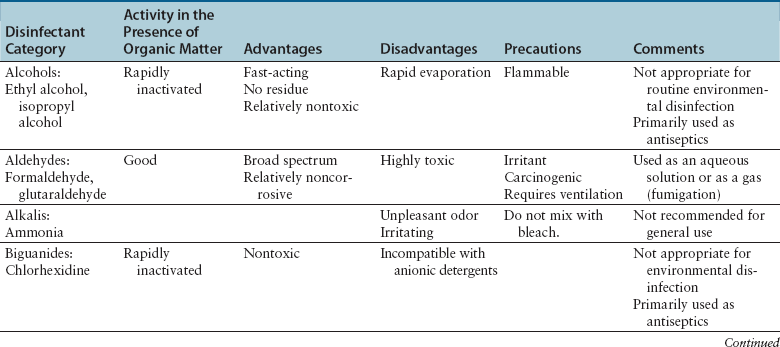

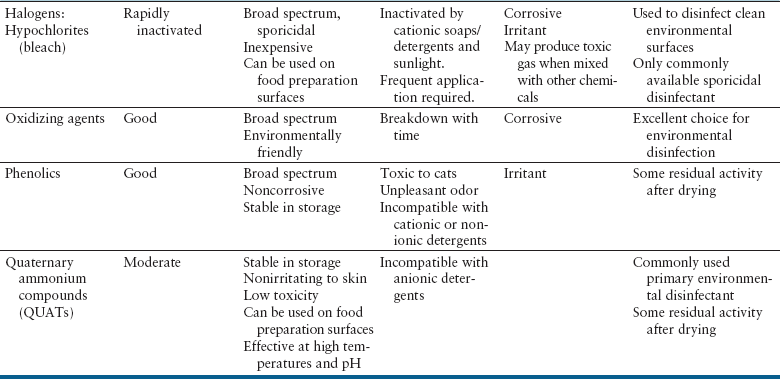

Chapter 11 • A hospital infection control program consists of infectious disease control personnel, a written protocol, training, and documentation. The aim of such a program is to reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired infections among patients, staff, and visitors to a small animal hospital. • The infection control program describes the requirement for practices that optimize hygiene such as hand washing, the use of protective clothing, cleaning and disinfection, and appropriate disposal of infectious agents. The protocol can also be used to educate staff about specific transmission precautions for infectious diseases seen within a practice. • This chapter describes the infection control program and important components of an infection control protocol, including the advantages and disadvantages of various methods of sterilization, disinfection, and antisepsis used in small animal hospitals. • Information in this chapter also has relevance to infection control in shelters and in breeding and boarding facilities. The objective of a hospital infection control protocol is to provide a standard procedure for the control of infectious diseases in the hospital, in order to minimize animal-to-animal, animal-to-human, and human-to-animal transmission of pathogens. Adherence to the infection control protocol can also reduce transmission of infectious agents between personnel through increased hand washing and reduction of fomite contamination. The infection control protocol is a legal document and should be regularly updated by a designated hospital infection control officer or committee. Each hospital should develop a protocol that is tailored to address specific practice requirements and the hospital design, purpose, and equipment used. Additional special precautions may need to be described for hospitals that see avian and exotic pet animal species, and in geographic locations where serious zoonotic diseases such as rabies and plague are endemic (see Chapters 13 and 55). The infection control protocol details practices that optimize hygiene such as hand washing, the use of protective clothing, cleaning and disinfection, and appropriate disposal of infectious agents. Specific infectious disease control procedures to be followed in different areas of the hospital (radiology, surgery, the intensive care unit, isolation, wards) can be included, as well as policies on antimicrobial use. The protocol can also be used to educate staff about routes of transmission, the potential for zoonotic transmission, specific transmission precautions for infectious diseases that are seen within the practice, and immunization requirements, such as those for rabies (see Chapter 13). Frequent and proper hand and wrist washing to remove transient flora on the hands has been proven as the most important component for prevention of the spread of infectious diseases in human hospitals.1 Signs that outline proper hand-washing technique, including the use of paper towels to turn off the faucet, posted adjacent to basins around the hospital can improve compliance among staff. Online videos that demonstrate proper hand-washing technique are available for educational purposes.2 Guidelines for hand washing are shown in Box 11-1. Antibacterial soap should be used, and all surfaces of the hands should be rubbed together, which should include the backs of the hands, between the fingers, and under the fingernails, for a total hand-washing time of at least 20 seconds. In order to prevent chapped skin, which can harbor bacteria, water used for hand washing should not be too hot, and hand lotion should be applied regularly. Behaviors such as keeping fingernails short, avoidance of artificial and/or polished fingernails or hand jewelry, or wearing jewelry on a chain around the neck instead of on the hand can be encouraged. Meticulous hand hygiene is particularly important for personnel who work frequently with immunocompromised animals, such as emergency and critical care personnel. The use of touch-free taps and paper towel dispensers can also reduce transmission of bacteria during hand washing. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are a more convenient form of sanitization. These can be provided in multiple locations around a hospital, or travel-sized bottles can be carried in a coat pocket. At least one to two full pumps or a 3-cm diameter pool of the product should be dispensed onto one palm. All surfaces of the hands and wrists should be rubbed with the product until it has dried. Use of soap and water, rather than hand sanitizer, is recommended when there is gross contamination with organic matter, or when exposure to alcohol-resistant pathogens such as Clostridium spp. spores or parvovirus might have occurred. However, the availability of hand sanitizers improves compliance in busy hospital situations, is associated with lower rates of dermatitis than medicated soaps, and is recommended for routine hand sanitation in human health care settings by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO).3,4 The use of gloves prevents contamination of the hands with microorganisms, prevents exposure to bloodborne pathogens, and reduces the risk of transmission of microorganisms from personnel to animals. However, gloves are not a substitute for proper hand hygiene. Guidelines for wearing disposable gloves are shown in Box 11-1. Gloves should be promptly removed after use, before other surfaces are touched, and hands should then be washed. If a glove is torn or punctured, it should be removed and replaced as soon as possible. Staff should be encouraged to wear dedicated hospital attire that is not worn elsewhere, so that hospital pathogens are not transported to and from locations outside the hospital. At the minimum, protective clothing such as clean laboratory coats or hospital scrubs and closed-toe shoes must be worn in nonsurgical areas. Sleeves must be short enough or rolled up to expose the wrists, and laboratory coats changed whenever gross soiling occurs. In the absence of gross soiling, coats should be changed daily. If neckties are worn, they must be secured in place by an outer layer of clothing or a tie pin so that they cannot be contaminated as a result of contact with patients or environmental surfaces and act as fomites, as has been shown to occur in human hospital environments.5 Long hair must be tied back so that it does not drape on animals and hospital surfaces. Face shields and a clean gown should be worn during procedures that are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood and body fluids. Gowns must be made of impervious material and tied on securely and correctly. Soiled gowns must be removed as soon as they are no longer required and face shields cleaned. Dedicated operating room attire should be worn in surgical areas and should be changed after gross soilage and when leaving the operating room for the day. Caps and masks should be worn and hands thoroughly washed on entry to the operating room. There is no evidence that dedicated footwear or foot protection should be worn for prevention of surgical site infections in human patients, and major human guidelines do not advocate that footwear be addressed.6 Protective wear should be removed whenever staff members leave the operating room. Traffic in and out of the operating room should be limited to the minimum required for patient care. All animals seen at a veterinary hospital should undergo a history and physical examination by a veterinarian to determine the likelihood and nature of any transmissible infections that might be present. Ideally, client beds, blankets, collars, and leashes should not be brought into the hospital, where they could become contaminated. Animals should always be placed in cages that have been cleaned and disinfected appropriately. Disposable thermometer sleeves should always be used on thermometers. Equipment should not be shared between animals unless it has been cleaned and disinfected. Diets that contain raw meat and bones should not be fed or stored in the hospital, because they commonly contain and can potentially transmit foodborne gastrointestinal pathogens.7 The handling of sick animals should be minimized, unless required for patient care. Transmission-based precautions are instituted for selected patients that are confirmed to be or suspected to be infected or colonized with important transmissible pathogens. Transmission-based precautions are used in combination with standard precautions. In the human hospital setting, three types of transmission-based precautions have been developed—airborne, droplet, and contact precautions (Table 11-1).8 Airborne precautions are used to prevent the transmission of diseases by droplet nuclei (particles <5 µm). Transmission by droplet nuclei occurs with diseases such as measles, varicella, and pulmonary tuberculosis. The precautions for human patients involve isolation in a single-bed, negative-pressure room and the wearing of high-density respirator (N95) masks. These resemble surgical masks but filter 1-µm particles with an efficiency of at least 95% and must be properly fitted. Airborne contact precautions are rarely necessary in hospitals that treat only dogs and cats, but could be considered when animals suspected to have pneumonic plague, tularemia, or Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Droplet precautions are used to prevent transmission by large-particle aerosols and do not require a negative-pressure room. Droplet precautions apply to dogs and cats with transmissible respiratory disease. Contact precautions are indicated for animals with infections that can be transmitted by direct contact with the patient or through fomite contact. In contrast to human hospitals where patients can be more readily isolated in single-bed rooms or cubicles, isolation of veterinary patients can be more difficult because of the close proximity of one animal to another. Floor contamination with secretions and excretions can also occur more readily. Isolation rooms are available in many veterinary hospitals, but they may be poorly visible and/or accessible and may not provide access to an oxygen source or be amenable to intensive monitoring and care. For some animals (especially puppies and kittens) suspected to have a transmissible disease, housing in a general ward or ICU area with as much physical and procedural separation as possible, and with strict infection control practices, may be acceptable (if perhaps not optimal). Once a diagnosis is confirmed, the animal should be moved immediately to isolation whenever possible. Patients chosen for strict isolation vary based on the specific situation and facilities available, but suggestions are provided in Box 11-2. Potentially contaminated waste should be disposed of in an approved plastic bag in a container labeled on all exposed sides with “biohazardous waste.” Blood-soaked materials, infected materials, and empty fluid bags should all be placed in biohazardous waste containers. Care should be taken not to contaminate the outside of the container during disposal. The lid of the biohazardous waste container must close properly. Blood and body fluids should be inactivated with an appropriate disinfectant (e.g., bleach or accelerated hydrogen peroxide) and allowed to stand for 10 minutes before disposal. Disposal regulations may vary depending on local laws, but liquid waste should not be disposed of into storm drains. Disinfection is the process that eliminates many or all microbes from inanimate objects, but not bacterial spores. Factors that influence the efficacy of disinfection include the type of microorganism present, their number, the amount and type of organic matter present, the presence of biofilms, and the porosity of the surface to be disinfected. Some disinfectants kill spores at high concentrations and with prolonged exposure times. These are known as chemical sterilants. At low concentrations and short contact times, chemical sterilants inactivate all microbes except large numbers of bacterial spores and are known as high-level disinfectants. Low-level disinfectants inactivate most vegetative bacteria, some fungi, and enveloped viruses, but not bacterial spores. Intermediate-level disinfectants inactivate mycobacteria, vegetative bacteria, most viruses, and most fungi (Tables 11-2 and 11-3). TABLE 11-2 Characteristics of Selected Disinfectants Source: Modified from the Canadian Committee on Antibiotic Resistance. Infection Prevention and Control Best Practices for Small Animal Veterinary Clinics, 2008; http://www.wormsandgermsblog.com/2008/04/promo/services/infection-prevention-and-control-best-practices-for-small-animal-veterinary-clinics/. Last accessed May 15, 2012.

Infection Control Programs for Dogs and Cats

The Hospital Infection Control Protocol

Standard Precautions

Hand Hygiene

Hospital Attire

Surgical Areas

General Animal Handling Precautions

Transmission-Based Precautions

Isolation

Handling of Potentially Infectious Materials and Waste

Hospital Cleaning, Disinfection, and Sterilization

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Infection Control Programs for Dogs and Cats

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue