36 Hyphaema

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

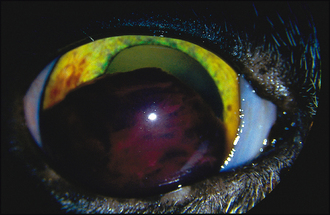

Ophthalmic examination will include careful assessment of the globe for evidence of trauma – blunt or penetrating. Subconjunctival haemorrhage is frequently present following blunt trauma, while a corneal injury might be noted following sharp trauma. Fluorescein testing should be performed. Vision should be assessed. The amount of blood present in the anterior chamber will determine the appearance – a small bleed will settle to the ventral anterior chamber and a fluid line will be noted, while a more severe bleed can present with the anterior chamber full of blood such that no intraocular structures can be evaluated (Figure 36.1).

If the pupil can be seen, reflexes should be checked. If it cannot be seen, then the indirect response in the fellow pupil is important since this can indicate whether the fundus and optic nerve in the affected eye are responsive to light. If there is no constriction of the fellow pupil when light is shone into the affected pupil, this might suggest severe posterior segment damage and the prognosis for any return of vision is guarded. The dazzle reflex should be similarly checked and carries comparable prognostic information.

The colour of the blood can give an indication regarding chronicity – in acute bleeds it will be bright red, while if present for several days it becomes much darker in colour. If clotted there might be ‘clumps’ seen in the pupil, mixed with fibrin and other inflammatory mediators (Figure 36.2), while unclotted blood will sink to the ventral anterior chamber.

The fellow eye should be evaluated. If trauma is not the cause for the hyphaema, then a systemic disease could be present. In many such cases there will be bilateral ocular abnormalities, although these are not necessarily symmetrical. Small petechiae might be visible on the iris providing it is not very darkly coloured when appreciation of such haemorrhages is much more difficult. Fundus examination might reveal retinal haemorrhages or vessel abnormalities suggestive of a vasculitis or hypertension. Retinal detachment might be present. If vitreal haemorrhage is present, this will be seen as strands or clumps of blood obscuring the view of the fundus (see Case 33.2 and Figure 33.4).

Intraocular pressure should be measured, if possible, and can be normal, reduced or elevated in cases of hyphaema. Treatment choices will vary according to intraocular pressure and hence measurement is important.

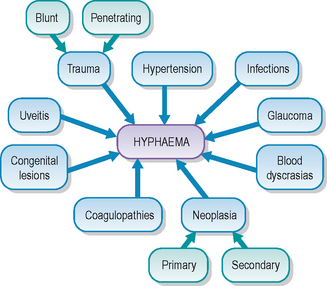

There are many potential causes for hyphaema (see Figure 36.3):