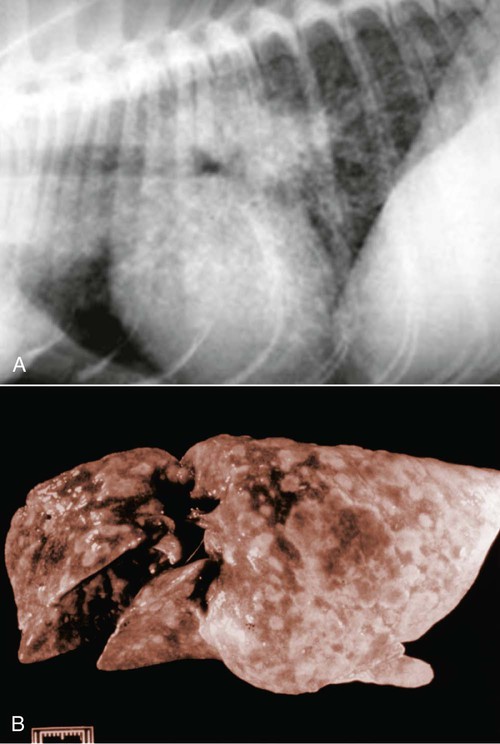

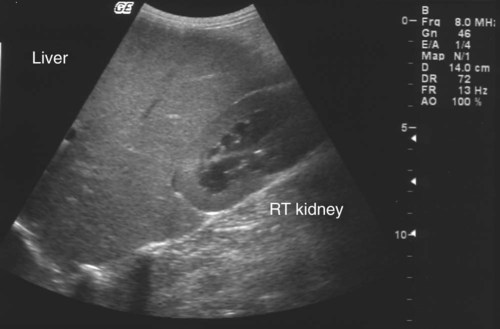

The etiologic agent of American histoplasmosis is the soilborne, dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. This organism can survive wide fluctuations in environmental temperature and prefers areas with warm (mean ambient temperatures of 22° C to 29° C [71° F to 84.2° F]), moist (annual precipitation 35 to 50 inches), and humid (67% to 87%) conditions. These conditions are generally between latitudes 45 degrees north and 30 degrees south. H. capsulatum grows best and accelerates its sporulation in soil containing nitrogen-rich organic matter such as bird and bat excrements. Although most affected animals have exposure to outdoor environments, some affected cats have been housed exclusively indoors and have not traveled to endemic regions. This finding suggests that even accumulations of household dust or the potting soil of houseplants may be potential sources of infection.51 H. capsulatum is endemic throughout large areas of the temperate and subtropical regions of the world (Fig. 58-1). Although infections have been documented from every continent except Antarctica, they are most prevalent in the Americas, India, and southeastern Asia. In addition to dog and cat infections in the endemic areas, infection has been documented in dogs and cats in both Europe22,42 and Japan.32,34,34 The organisms in infections in Japan may include H. capsulatum var. farciminosum and H. capsulatum var. capsulatum.48 The organism H. capsulatum var. duboisii, the cause of African histoplasmosis, is confined to that continent, whereas H. capsulatum var. capsulatum (H. capsulatum) has been isolated from soil in 31 of the continental United States. Most clinical cases occur in the midwestern and southern United States and regions along the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers. Histoplasmosis can appear in traditionally nonendemic regions (e.g., California)31 if local environmental conditions are altered to favor fungal growth. Soil rich in bird or bat feces, such as where poultry is raised or in caves, respectively, is most likely to harbor the fungus. Obtaining a detailed travel history is important to identify patients that may have acquired infection while in endemic regions.23,31 The life cycle of H. capsulatum is similar to that of other dimorphic fungi. The free-living, environmentally resistant mycelial stage in soil at 25° C (77° F) produces macroconidia (5 to 18 µm) (see Fig. 54-15) and microconidia (2 to 5 µm) that are the source of infection for mammals. Histoplasmosis is probably acquired by inhalation of microconidia that are small enough to reach the lower respiratory tract. The incubation period after exposure in susceptible hosts is approximately 12 to 16 days.19 In the body at 37° C, the microconidia convert to the yeast phase in the lung and reproduce by budding. The yeast organisms are phagocytized by cells of the host’s mononuclear phagocyte system and undergo further intracellular replication. Infection may be grossly limited to the pulmonary tree; however, lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination of H. capsulatum can occur early in the course of the disease because of the intracellular location of the fungus. Severe clinical disease can result if the dose of infective spores is large or if the immune system of the host is compromised. The cellular immune system, predominantly involving cytokine-mediated macrophage killing, will rapidly bring the infection under control in most patients. T-cell immunity is critical for clearance of the organism. In immunocompetent hosts, H. capsulatum may establish a dormant phase and may not be totally eliminated from the mononuclear phagocyte system.20 With subsequent immunosuppression, reactivation of infection can occur. Co-infection with Ehrlichia canis was observed in a dog that was subsequently diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma.8 Dissemination involves primarily organs that are rich in mononuclear phagocytes. In addition to phagocyte impairment, the fungus induces nonspecific anergy, as demonstrated in humans and mice with disseminated infections. The yeast cells overproduce interleukin-4, which at high levels can interfere with the cellular immune response. The yeast also synthesizes melanin or melanin-like compounds, as do other pathogenic yeasts, and this may be an important virulence factor.50 The occurrences of gastrointestinal (GI) histoplasmosis without respiratory tract involvement and of cutaneous histoplasmosis as the sole manifestation49 suggest that the GI tract or the skin may also be primary sites of infection. However, experimental studies have failed to produce GI disease reliably after oral administration of H. capsulatum spores. Histoplasmosis is the second most commonly reported systemic fungal disease in cats.18 Cats are very susceptible hosts and are at least as likely as dogs are to develop clinical histoplasmosis. The age range of cats affected with histoplasmosis is less than 2 months to over 15 years with a mean age of 3.9 years.18 Persian cats may be predisposed; no apparent sex predilection is present.18 Most infected cats have disseminated disease and exhibit a wide range of nonspecific clinical signs, including mental depression, weight loss, fever, anorexia, and pale mucous membranes.13 Coughing is uncommon, but dyspnea, tachypnea, and abnormal lung sounds are found in more than one-half of affected cats. Other frequent findings include peripheral or visceral lymphadenomegaly, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly that may be associated with icterus. One cat in Japan had granulomatous lesions in the colon.34 Ocular involvement was identified in as many as 24% of cats in a large case series18 and may include granulomatous blepharitis, conjunctivitis, chorioretinitis, panuveitis,52 or panophthalmitis, retinal detachment, and optic neuritis.29,31,31 Some cats have had osseous lesions with associated soft tissue swelling or joint effusion and lameness. The skin is infrequently affected with nodular or ulcerated lesions.54 Localizing signs, such as oral ulcers,37 ocular involvement,52 or spinal cord lesions,65 may be the predominant finding; however, necropsy reveals disseminated infection in almost all cases.18 Rare clinical findings include nasal polyps, vomiting, diarrhea, or signs of central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Histoplasmosis has been reported in dogs ranging in age from 2 months to 14 years. Most affected dogs are young (under 5 years), and no apparent sex predilection is present. Pointers, Weimaraners, and Brittany spaniels as well as terriers and sporting and working dogs are at increased risk for contracting histoplasmosis.60 Inappetence, weight loss, and fever unresponsive to antibacterial therapy occur in most dogs with histoplasmosis (Fig. 58-2). In some dogs, the clinical signs may be limited to the respiratory tree and include dyspnea, coughing, and abnormal lung sounds. However, in most dogs, clinical signs result from disseminated histoplasmosis with GI involvement.14,38 Signs of large-bowel diarrhea with tenesmus, mucus, and fresh blood in the stool are the most common clinical findings. Pale mucous membranes often are found in patients with bone marrow involvement or GI blood loss. Extensive Histoplasma infiltration of the small bowel can cause a voluminous, watery stool with an accompanying protein-losing enteropathy (Fig. 58-3). Hepatomegaly, visceral lymphadenomegaly, splenomegaly, icterus, and ascites are frequent associated findings. Unusual signs include vomiting, peripheral lymphadenomegaly, and lameness or joint swelling as a result of osseous or joint infection. Ocular lesions or skin lesions as described for cats have also been reported in the dog. These clinical signs may be the only obvious clinical findings and often are characterized by a chronic course of disease.41 Neurologic involvement, recognized with dissemination of infection in dogs, is rare.45 With the exception of one dog with disseminated histoplasmosis,48 lesions in infected dogs from Japan have been confined to the skin or gingiva, and pulmonary or GI lesions have not been grossly apparent.32 The most common hematologic abnormality in both dogs and cats with disseminated histoplasmosis is normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia. The anemia probably results from chronic inflammatory disease, Histoplasma infection of the bone marrow, and intestinal blood loss in GI disease. Thrombocytopenia may be observed in as many as one-half of dogs and one third of cats with histoplasmosis.61 Leukocyte counts are variable. Neutrophilic leukocytosis with monocytosis and eosinopenia is found most frequently. Leukopenia has also been reported. In a survey of neutropenic dogs, histoplasmosis was associated as a risk factor.7 Severe pancytopenia has been observed in some cats; no hematologic abnormalities were identified in others. Histoplasma organisms may be found during routine blood film examination in circulating monocytes, neutrophils, and, rarely, eosinophils. Performing 1000-cell differential counts or examining buffy coat smears will enhance detection of infected cells. Biochemical profiles are usually unremarkable in dogs with pulmonary histoplasmosis. Hypoalbuminemia is a fairly consistent finding in cats with disseminated histoplasmosis. Some cats have had hyperproteinemia, hyperglobulinemia, mild hyperglycemia or hyperbilirubinemia, and elevations of alanine aminotransferase activities. Dogs with disseminated disease may have hypoproteinemia with severe hypoalbuminemia as a result of intestinal blood loss or protein-losing enteropathy. Involvement of the liver in affected dogs may cause hypoalbuminemia; hyperbilirubinemia; elevated serum alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or alkaline phosphatase activities; and abnormal results on liver function tests.10,61 Hypercalcemia (probably associated with granulomatous disease) has been reported in several cats.29 Thoracic radiographs of dogs and cats with active pulmonary histoplasmosis usually exhibit a linear or diffuse pulmonary interstitial pattern associated with granulomatous fungal pneumonia (Fig. 58-4, A). The infiltrates often are coalescing and may appear miliary or grossly nodular. True alveolar involvement in pulmonary histoplasmosis is rare. Hilar lymphadenomegaly is common in dogs but rare in cats (see Fig. 58-4, B). Pleural effusion occurs infrequently in the dog. Pulmonary calcification, indicative of inactive pulmonary histoplasmosis, is occasionally seen in dogs. The interpretation of abdominal radiographs in dogs with GI histoplasmosis may be difficult because of the emaciated condition of the patient or the presence of abdominal fluid. Noncontrast studies may demonstrate hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or ascites (Fig. 58-5). Barium contrast examination may reveal irregularities of the intestinal mucosa and thickening of the intestinal walls. Ultrasonographic examination of dogs with liver involvement may reveal hyperechoic liver parenchyma (Fig. 58-6).10 Hepatomegaly, nodular and infarctive lesions, splenomegaly, and mesenteric lymphadenomegaly have also been observed.6 Osseous involvement with histoplasmosis is rare in the cat and even less common in the dog. The typical radiographic appearance of bony lesions is a mixed pattern of osteolysis, subperiosteal bone proliferation, and periosteal new bone formation (Fig. 58-7). Intra-articular infection has been observed in both dogs and cats but is rare.30 In the cat, Histoplasma most frequently infects the metaphyses of long bones with a predilection for the bones of and adjacent to the carpal and tarsal joints. Endoscopic examination of dogs with colonic histoplasmosis reveals mucosal thickening, granularity, friability, and ulceration.38 Cytologic or histologic examination of rectal scrapings and biopsy samples usually reveals large numbers of Histoplasma organisms. Histoplasma organisms may also be observed in small intestinal biopsy samples from cats.37 Transtracheal wash (TTW), endotracheal wash (ETW), and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) have been used as methods to evaluate patients with suspected pulmonary mycotic infections in which organisms were not recovered by other noninvasive methods.23,27,27 Generally, BAL is superior to TTW or ETW because the collected cells are more representative of the interstitial and deeper portions of the airway. BAL and ETW require anesthesia, and BAL causes more respiratory compromise than do TTW or ETW. Patients must be evaluated carefully before undergoing anesthesia. Fungal organisms may not be numerous in specimens recovered by airway washing procedures and are less likely to be seen with chronic than with acute infections.59 The sensitivity of these tests has not been thoroughly evaluated.

Histoplasmosis

Etiology

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Clinical Findings

Cats

Dogs

Diagnosis

Clinical Laboratory Findings

Medical Imaging Findings

Endoscopic Findings

Transtracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine