Chapter 29 Histopathology

Stomach

The stomach is divided into several anatomic regions that differ in histologic character and function. Most proximal is the cardia, which surrounds the entry of the esophagus into the stomach, and most distal is the pyloric antrum leading to the sphincter that separates the stomach from the duodenum. In between, and occupying about two-thirds of the stomach, is the gastric body. The gastric fundus is an outpouching of the gastric body at its proximal end where it joins the cardia. This nomenclature is not absolutely standardized, and many authors refer to the combined fundus and body as the “fundic region” and habitually refer to biopsies from this region as being from “fundic mucosa.”1,2 Each of these regions has distinctive histologic appearance, but the transition from one portion to the other is not abrupt and in some biopsies the mucosa has an appearance intermediate between one region and the other.

Almost all gastric biopsies, whether endoscopic or full thickness, are taken from the fundic mucosa and from the pyloric antrum. In all regions, the mucosa is divided into three horizontal zones. In the fundic/body region, the deepest 60% to 80% of the mucosa is occupied by densely packed branched glands consisting of mucus-producing cells and a variety of secretory cells. The glands are connected to the luminal surface by a narrow neck known as the foveola. In contrast to the more distal portions of intestine, the germinal population for all of the gastric epithelium lies at the junction between the glands and the foveolae, a region known as the isthmus, rather than at the base of the glands (Fig. 29-1). These germinal cells migrate upward to replenish the mucus neck cells and surface epithelium, and downward to repopulate the glands as part of normal mucosal turnover and in the event of unexpected epithelial loss. The overall mucosal turnover time is 4 to 5 days—a time that dictates the speed of wound healing, and the rate at which shallow ulcers disappear. The risk of a false-negative biopsy result when investigating episodic gastric disease has not been sufficiently emphasized.

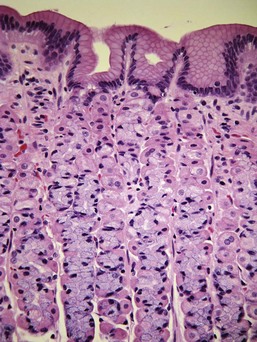

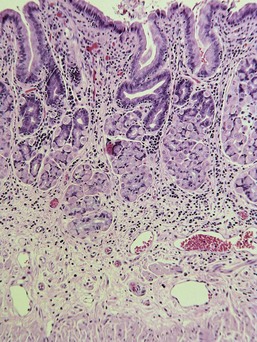

The glands are separated from the underlying muscularis mucosa by a layer of dense fibrous tissue that varies substantially in thickness. They are separated from one another by a very small amount of fibrovascular lamina propria containing a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, mast cells, and eosinophils. In the normal fundic stomach, the fibrous tissue and the leukocytes are most visible in the superficial 20% of the mucosa. The deeper glands are packed against each other with essentially no intervening lamina propria (Fig. 29-2). Defining the normal reference range for the fibrous tissue and for each cell population is essential to the proper identification and classification of gastric inflammatory disease—a goal that remains elusive.

Histologic Classification of Gastric Disease

Gastric Ulceration

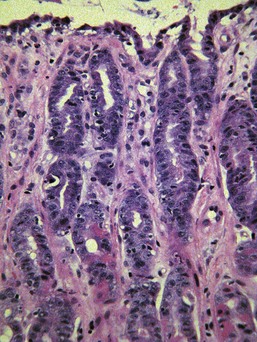

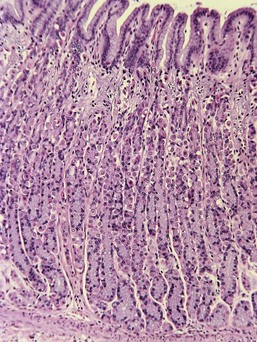

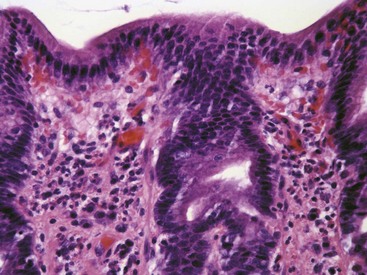

Ulceration caused by mechanical abrasion is usually shallow and transient. Like other portions of the alimentary system, shallow ulcers heal within hours by flattening and sliding of adjacent epithelium followed by replacement of mucus cells generated by a transient increase in mitotic activity within the isthmus zone at the base of the foveolae. The regenerating epithelium is flatter and more basophilic, with little mucus and slight irregularity in orientation of the nucleus (Fig. 29-3). Shallow ulcers heal completely within just a few hours. The adjacent superficial lamina propria will usually have at least some edema and perhaps even hemorrhage, but the leukocytic reaction is usually minimal. A few neutrophils may be found in the very superficial lamina propria or intermingled with some fibrin and mucus filling in the ulcer. The paucity of leukocytes is in part because the injured tissue is sloughed into the intestinal lumen so that there is little chemical stimulus for leukocyte recruitment, and partly because the stomach has almost no resident bacteria to contaminate the wounds. With deeper or more persistent ulceration, there will be more obvious hyperplasia and basophilia within the isthmus region reflecting a greater need for mitotic replacement of injured epithelium. Deeper ulcers that have destroyed the isthmus and portions of the lamina propria will take longer to heal and will require stromal proliferation to build a scaffold for effective epithelial healing, but remodeling is extremely effective and it is rare to see any permanent residual scarring. Regardless of the severity of the original lesion, the usual outcome is histologic normalization (Fig. 29-4).

Causes of ulceration other than mechanical abrasion are numerous and include histamine-induced ulceration in dogs with mast cell tumor,3,4 accidental chemical ingestion, ulcers caused by steroidal and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory (and occasionally other) drugs,5–7 and exercise-induced ulcers that are best documented in racing sled dogs.8 In general, the histologic character of the ulceration provides no clue as to the pathogenesis. Careful estimation of the age of the lesions (distance of epithelial sliding, restoration of the normal columnar epithelial shape and normal cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and the maturity of subepithelial fibrosis) will often allow the clinician to identify the causative drug or event. Progression to perforation is rare and usually requires continued application of the injurious stimulus (e.g., continued administration of ulcerogenic drugs or persistent histamine production by a mast cell tumor).

Gastric Necrosis Other Than Ulceration

Uremic gastropathy occurs almost exclusively in dogs and its exact pathogenesis remains unknown. The distinctive lesions include mineralization and necrosis of the parietal cells occupying the middle third of the gastric mucosa, mineralization of basement membranes of the glands and of the submucosal blood vessels, and mineralization of degenerate smooth muscle within the muscularis mucosa or even tunica muscularis (Fig. 29-5). Mineralization of submucosal blood vessels may become extensive, involving the full thickness of the vessel wall and accompanied by medial necrosis and endothelial destruction.9

Gastric Mucosal Fibrosis and Atrophy

Varying degrees of mucosal fibrosis and glandular atrophy are common in biopsy samples of the gastric mucosa. Such lesions have received almost no attention in the veterinary literature, but are common sources of confusion for pathologists attempting to interpret endoscopic biopsies. Some have referred to this as “atrophic gastritis,” with no proof that the pathogenesis of the fibrosis is linked to previous inflammatory disease. In the only study to specifically address this question, noninflammatory atrophy and/or fibrosis was seen in 128 of 482 vomiting dogs. Similar lesions were also seen in five of 19 clinically healthy dogs.10 It is not clear whether the fibrous tissue represents a true increase in the volume of collagen or simply a condensation of resident collagen subsequent to glandular atrophy. The two lesions (mucosal fibrosis and glandular atrophy) are almost always concurrent.

There remain numerous questions related to gastric atrophy and fibrosis, including these:

1. What is the normal amount of fibrous tissue within the lamina propria in different portions of the stomach?

3. How commonly is such fibrosis a marker of previous inflammatory disease?

5. Is it functionally significant, significant only as a diagnostic marker, or not significant at all?

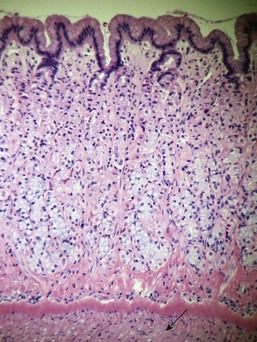

Normally, the glands within the fundic mucosa lie against each other with almost no intervening fibrous tissue. There is a small amount of loose connective tissue among the foveolae, and there can be substantial fibrous tissue separating the base of the glands from the muscularis mucosa. The amount of fibrous tissue in this deep location is greater in cats than in dogs. In cats there is also a distinct, very dense band of hyalinized fibrous tissue just superficial to the muscularis mucosa, known as the lamina densa (Fig. 29-6). Within the pyloric antrum there is substantially more fibrous tissue throughout the lamina propria, so any diagnosis of mucosal fibrosis in the pyloric stomach should be viewed with skepticism.

Dogs and cats with chronic gastritis often have persistent mucosal edema that matures into fibrosis. Concurrent inflammatory injury to the gastric glands is followed by regeneration that creates “nests” of hyperplastic glands embedded within the fibrous tissue (see “Atrophic Gastritis” section). It is also common to see the combination of fibrosis and glandular nesting with no evidence of active inflammation and no clinical history of gastric disease (Fig. 29-7). The glands within these nests usually have at least some degree of atrophy of the parietal cell mass with a relative increase in the prominence of the columnar mucus-producing epithelial cells. The combination of glandular atrophy, dysplastic repair, and mucus (intestinal) metaplasia represents a strong risk factor for progression to gastric carcinoma in people,11 an association that has not been proven in dogs.

Gastritis

Normal Gastric Mucosal Cellularity

Only three studies address the critical question of the reference range for leukocyte types in the normal canine gastric mucosa. The first reports findings from examination of endoscopic biopsies from 20 clinically normal young adult dogs (Table 29-1).12 These dogs had no history of vomiting or diarrhea for at least 2 months prior to entering the study, and were all fed a standardized diet and had the same husbandry conditions. Leukocytes were identified with light microscopy and immunohistochemistry, and were counted separately in both superficial and deep lamina propria in “mucosal units” of 250 µm2 (corresponding to approximately one-half of a ×40 microscopic field). Within the superficial lamina propria of the fundic mucosa, this corresponds to a rectangle of tissue incorporating three adjacent foveolae and the associated lamina propria, and extending vertically to the level of the first parietal cell. Within the pyloric antrum, the “mucosal unit” corresponds to an area of lamina propria bordered by two adjacent foveolae, with its deep border capturing the most superficial portion of the gastric glands.

Table 29-1 Leukocyte Numbers in the Superficial Gastric Mucosa of Healthy Dogs

| Cell Type | Superficial Fundic* | Superficial Pyloric† |

|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes (CD3 and CD79) | 8.4 (1.5-27.0)‡ | 22.9 (11.5-32.0)§ |

| Plasma cells | 1.6 (0-5.8)‡ | 6.8 (0.5-15.5)§ |

| Eosinophils | 0.5 (0-2.0)‡ | 2.7 (0-6.0)§ |

| Total leukocytes** | 10.4 (3.6-26.2)‡ | 32.6 (20.0-46.5)§ |

* Number of cells within a rectangle of lamina propria encompassed horizontally by three foveolae, and vertically to the level of the first parietal cell.

† Number of cells in a square of lamina propria encompassed by two adjacent foveolae with the deep border at the foveolar–glandular junction.

‡ Mean (range) of three cell counts in each of 20 dogs.

§ Mean (range) of two cell counts in each of 8 dogs.

** Sum of CD3+ and CD79+ lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils, but excluding mast cells and unidentified cells.

Source: Adapted with permission from Southorn EP. An improved approach to the histologic assessment of canine chronic gastritis. DVSc Thesis, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 2004.

The first of these studies was based on 18 client-owned dogs with GI disease and eight dogs euthanized for nonenteric disease. None of the dogs had been treated with antibiotics, corticosteroids, or antacids in the months prior to sampling. Lesions within the fundic mucosa alone were graded by two pathologists using pictorial templates adapted from the human Sydney system that depicts various severities of atrophy, fibrosis, and cellular infiltration. The results from the eight “normal” dogs were not separately identified when tabulating the results (presented as the mean grading results from all 26 dogs).13

The second and much larger study provided not only a series of pictorial templates, but also a brief text to guide the grading of GI biopsies, including those from stomach. It included pictorial templates for leukocyte accumulations, fibrosis, ulceration, and other parameters within the fundic and antral mucosa.14

In both of these latter studies in which the pictorial templates were specifically designed to reduce interobserver variation, the results showed poor correlation among grading scores assigned by different pathologists. Painful though it is, we must collectively confront the reality that it is essentially impossible to compare results from different studies claiming to evaluate causation or therapy of “gastritis.” In most published studies of gastritis in either dogs or cats, the descriptions of leukocyte numbers or the published photographs of lesions claimed to represent mild and even moderate gastritis would be considered “normal” using criteria in the three studies listed previously. This is particularly true of the many studies attempting to establish the pathogenicity of Helicobacter spp. for dogs and cats in which any histologic changes were described as mild increases in superficial mucosal cellularity.15–23

Histologic Classification of Gastritis

The previously mentioned problems notwithstanding, there is no doubt that genuine gastritis does exist and is quite common. Most cases are part of more generalized GI inflammatory disease,24 but some are purely or predominantly gastric. There is no evidence that histologic classification based on the distribution or type of leukocytes has relevance to pathogenesis, treatment, or prognosis, nor is there evidence to the contrary. Thus it is appropriate to use (at least for the moment) a classification system that reflects histologic changes, with the expectation that at least some of these differences will eventually prove to have etiologic, therapeutic, or prognostic significance.

Superficial Mucosal Gastritis

Most examples of gastritis in dogs and cats involve leukocyte infiltration of the superficial 20% of the mucosa. In almost all cases, the surface epithelium remains normal. In most cases, lymphocytes and plasma cells predominate, but there are almost always at least some eosinophils. Neutrophils are rarely present, but their presence almost always means nearby or recent ulceration. There may be a concurrent increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes, and in cats there can be an increase in intraepithelial large granular lymphocytes (formally known as globular leukocytes) that are of unknown significance. Edema accompanies the leukocytes and there is often activation of resident fibroblasts and blood vessels (Figs. 29-8 and 29-9).

It has been traditional to describe the predominant cell type (lymphocytic, plasmacytic, eosinophilic) as part of the classification system, but there is no evidence that this is useful.7,14,24 First, there is no uniformity between laboratories in how well eosinophils, mast cells, or even plasma cells are stained. Second, pathologists differ in defining what proportion of cells is required before that cell type is considered “predominant.” Some will diagnose a lesion as “eosinophilic” if they believe that the eosinophils are the most numerous cells entering the tissue on an hourly basis, even if they are outnumbered by lymphocytes or plasma cells that have accumulated over weeks and months. Others use a more traditional approach and name the lesion based on the cell type that is most numerous within the tissue at the time of assessment. That means that almost any chronic gastritis will be classified as “lymphoplasmacytic.” Until everyone uses the same convention for naming such lesions, subclassification based on the predominant cell type will remain unreliable. It makes more sense to simply list each identifiable cell type as a percentage of the total infiltrate, so that such information can later be analyzed to see if it influences therapeutic response or other clinical parameters.

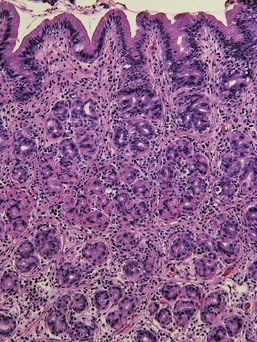

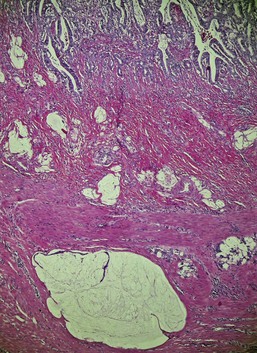

Transmucosal Gastritis

Approximately 30% of samples identified as having gastritis by conservative histologic criteria have an increase in leukocytes with variable degrees of edema and/or fibrosis throughout the full thickness of the lamina propria, causing separation of the gastric glands from each other and from the underlying muscularis mucosa (Figs. 29-10 and 29-11). There usually is no obvious necrosis within the glands or along the surface. Lymphocytes and plasma cells predominate, but eosinophils are often conspicuous and sometimes even predominant.

Atrophic Gastritis

Atrophic gastritis is a purely descriptive name for chronic gastritis that combines the elements of chronic inflammation, glandular atrophy, regenerative glandular nesting, and mucosal fibrosis. Lymphofollicular hyperplasia may accompany these changes. There is reduction in overall mucosal thickness and in most cases an obvious reduction in the number of parietal cells with a corresponding absolute or relative increase in the proportion of mucus-producing epithelial cells within the glands. If there are functional consequences to the reduction in glandular mass, they are rarely recognized clinically. Pathologists are not uniform in the criteria used to make this diagnosis, so it is difficult to assess the scattered literature related to pathogenesis and clinical significance. Atrophic gastritis may be just the residual lesion of transmucosal gastritis described previously. Atrophic gastritis has also been used as the name for the parietal cell atrophy and neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia that precedes the development of anaplastic and neuroendocrine gastric carcinomas in Norwegian Lundehund dogs with a distinctive, familial protein-losing enteropathy.25

Etiologic Classification of Gastritis

The majority of cases classified as gastritis by histologic criteria have no identified cause. The list of potential causes includes infectious agents, chemical irritants, toxic plants, and immune-mediated diseases.7 Most of the chemical and plant irritants cause transient gastric ulceration rather than true gastritis, and the inclusion of various allergic or other immune-mediated pathogeneses is based on assumptions rather than proof. Because the stomach is not a site of any significant protein absorption, assumptions of immune-mediated disease may be more appropriate for small intestine than stomach.

Parasitic Gastritis

Among the nematode parasites that may infect the stomach and cause histologic lesions, the only ones usually considered of potential significance are Physaloptera and Ollulanus. Gnathostoma and Cylicospirura may cause small submucosal suppurating granulomas, but they do not cause clinical signs. Infection with Physaloptera has been reported to cause persistent vomiting in dogs, and elimination of the worms following treatment resulted in reversal of clinical signs.26 Descriptions of histologic lesions are few and vague.

Ollulanus is sometimes listed as a cause of vomiting in cats. It has been described as a cause for fibrosis, lymphofollicular hyperplasia, and increased intraepithelial large granular lymphocytes in cats, but in the original report there was no clinical disease associated with the infection.27 In some cats the worms can be seen embedded within the foveolae, with no histologic changes. The association between Ollulanus infection and apparent increases in intraepithelial large granular lymphocytes remains unproven. The latter is a frequent observation in the stomach and small intestine of cats with GI disease and is of unknown significance.

Cryptosporidiosis has been reported in the stomach of cats and dogs, but with no proof of pathogenicity.28

Pythiosis

P. insidiosum is an aquatic oomycete fungus found primarily in tropical and warm temperate climates. Most reported cases in dogs have been from the southeast United States, but the disease is seen worldwide. Lesions in the stomach have the same histologic character as those seen elsewhere: destructive coalescing necrotizing granulomas found randomly within submucosa, tunica muscularis, or within the serosa.29,30 The diagnosis depends on identifying characteristic fungal hyphae. These are often difficult to see without special stains (e.g., periodic acid-Schiff [PAS] or silver stain), but the necrotizing lesions throughout the stomach wall are not easily mistaken for anything else.

Helicobacteriosis

Helicobacter spp. are normal inhabitants of the surface and foveolae of dogs and cats. In dogs, most infections are with Helicobacter bizzozeronii or Helicobacter heilmannii, while in cats H. heilmannii and Helicobacter felis predominate. These large spiral bacteria are easily seen in routine endoscopic biopsies, and their detection is enhanced by the use of silver stains. More elaborate and sensitive detection methods (e.g., polymerase chain reaction [PCR] or tissue urease activity) are research tools rarely if ever used in a diagnostic setting. In the past 15 years, there have been at least nine studies specifically examining the relationship between Helicobacter infection, development of histologic lesions, and clinical disease. None of these studies has proven any causal relationship between infection and disease.13,15–20 All but one, however, have claimed that infection is associated with an increase in gastric mucosal leukocytes, fibrosis, and lymphoid follicles. The problem is that the increased leukocytes claimed to represent “gastritis” invariably fall within the normal range for gastric mucosal cellularity as established by Southorn and as subsequently adopted by the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Gastrointestinal Standardization Group.12,14 Most of those studies had no uninfected control against which to measure the claims for increased cellularity. Even if one were to accept the hypothesis that colonization by Helicobacter causes a small increase in mucosal leukocytes (including lymphofollicular hyperplasia), the most plausible explanation is that the Helicobacter simply represent an increased antigenic challenge to the resident mucosal leukocytes that respond in an entirely appropriate fashion, analogous to what occurs when gnotobiotic animals are first introduced to a “normal” bacterial flora.31

Gastric Proliferative Disease

Focal Adenomatous Hyperplasia

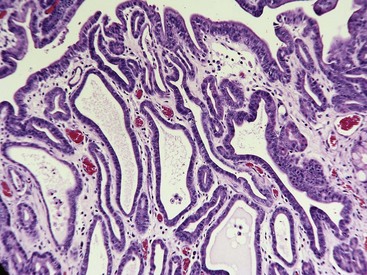

Focal adenomatous hyperplasia occurs in two forms. The more prevalent is focal pyloric mucosal hypertrophy in which the foveolae of the pyloric antrum become greatly exaggerated and form villus-like protrusions covered by mature and otherwise normal epithelium.32 The lamina propria sometimes contains an increase in eosinophils, but it is unknown whether those examples with eosinophils have a different pathogenesis than those without. It is unknown whether the eosinophils are involved in the development of the lesion, are the result of the lesion, or are unrelated.

The prevalence of these lesions is directly related to the frequency of endoscopy and many are clinically silent. They become significant only if they grow large enough and if they are located where they may cause pyloric obstruction. The diagnosis is difficult to confirm in endoscopic samples. If orientation and depth are both perfect, then the diagnosis is based on seeing the biopsy filled with superficial and foveolar epithelium with no glands because the increased thickness of the foveolar region occupies the entire capacity of the biopsy forceps (Fig. 29-12).

Gastric Neoplasia

Although a wide variety of neoplasms are reported within the stomach,35,36 the majority fall into one of three groups: gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, and smooth muscle tumors.

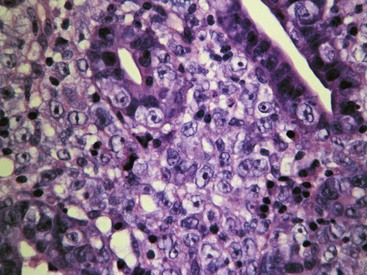

Gastric Carcinoma

It is traditional to subclassify gastric carcinomas based on histologic pattern (e.g. papillary, tubular, scirrhous),35 but most examples exhibit substantial regional variation that includes more than one subtype. In addition, there is no proven prognostic or therapeutic significance to these patterns so it is difficult to justify subclassification.

Lymphoma

Feline Gastric Lymphoma

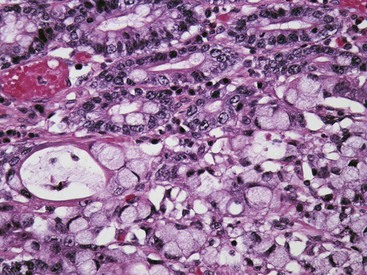

Large-cell (lymphoblastic) lymphoma is a more traditional lymphoma in the sense that it creates an unmistakable “mass” with early obliteration of mucosal architecture and invasion across the gastric wall. Perhaps because this disease is typically focal and limited to the stomach rather than being part of a more diffuse GI disease, the lesion is usually advanced at the time of initial diagnosis; consequently, histologic confirmation via endoscopic or ultrasound-guided core biopsies is not usually problematic. Most examples seem to arise from the diffuse lymphoid population in the superficial third of the gastric mucosa. The tumor spreads rapidly to destroy mucosal, submucosal, and muscular architecture, creating a diffuse sheet of monotypic large lymphocytes with nuclei at least twice the diameter of a red blood cell. Epitheliotropic behavior is rarely observed. In a series of 26 sequential examples studied in preparation for this chapter, all were confirmed as B-cell lymphomas. In a recent published study, nine lymphomas limited to the stomach were all immunoblastic B-cell lymphomas.37

Canine Gastric Lymphoma

Approximately 5% of all canine lymphomas arise within the alimentary tract, and only a small percentage of those arise within the stomach. Gastric lymphoma is substantially less prevalent than gastric carcinoma. It is perhaps for this reason that these tumors have received less attention than feline GI lymphomas. There have been no studies specifically of canine gastric lymphomas, and it is necessary to extrapolate from information derived from GI lymphomas in general. In four different published studies, 54 of 65 canine intestinal lymphomas subjected to immunohistochemical characterization were of the T-cell phenotype and the majority of the others were not classifiable.38–41 There are case reports of epitheliotropic lymphomas and of eosinophil-rich T-cell tumors, but it is not clear whether these are anything other than just variants of “ordinary” T-cell lymphomas.

Leiomyoma and Leiomyosarcoma

Any published estimates of the prevalence of smooth muscle tumors must be viewed with skepticism. In part this is because smooth muscle tumors are usually small and affect tunica muscularis only, so the majority do not cause clinical signs and cannot be detected endoscopically. Estimates of prevalence therefore differ in studies based on clinical signs as contrasted with postmortem studies.42,43 Further confusion arises from the fact that many of those tumors initially classified as leiomyosarcomas based on traditional histopathology have been reclassified as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) on the basis of immunohistochemistry (positive for CD117, negative for smooth muscle actin).44,45 Those papers addressed small intestinal, cecal, and colonic tumors rather than specifically looking at those in stomach, and in addition specifically addressed smooth muscle tumors initially diagnosed as poorly differentiated leiomyosarcomas rather than more common, mature leiomyomas. It is therefore a mistake to assume that all tumors previously diagnosed as well-differentiated smooth muscle tumors are at risk of having that diagnosis “overturned” by immunohistochemistry.

There is poor correlation between histologic appearance and biologic behavior. As a group, the smooth muscle tumors have a relatively good postoperative prognosis with prolonged postoperative tumor-free intervals and survival times regardless of histologic appearance.45 For those tumors that behave aggressively, the initial histologic appearance (i.e., leiomyoma vs. leiomyosarcoma) is not predictive.

Intestine

Small Intestinal Biopsies

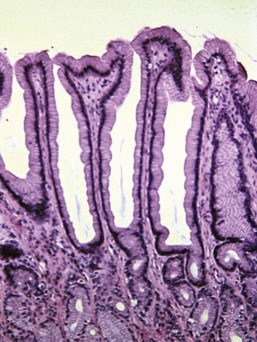

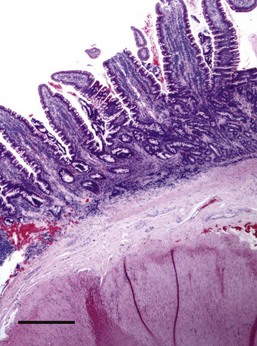

Assessment of tissue pathology has now become a routine component of the clinical evaluation of small intestinal disease. The traditional means of sampling the small intestine is by laparotomy and the collection of full-thickness surgical biopsies of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. This method of sample collection provides a greater chance of meaningful diagnostic outcome and it has been suggested that assessment of full-thickness biopsies increases the likelihood of successful diagnosis of alimentary lymphoma.13,35 Most clinicians are familiar with the benefits of fixing such samples while the tissue is stretched over a cardboard base to avoid artifactual “curling” of the specimen during fixation. The histology laboratory should then be able to prepare a longitudinal section of tissue with well-orientated mucosa through to serosa (Fig. 29-13). Laparoscopy may also permit collection of intestinal biopsies, but the diagnostic value of such samples has not been formally evaluated.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree