9 Gastrointestinal, Pancreatic, and Hepatic Disorders

Differentiation of Expectoration, Regurgitation, and Vomiting

Regurgitation

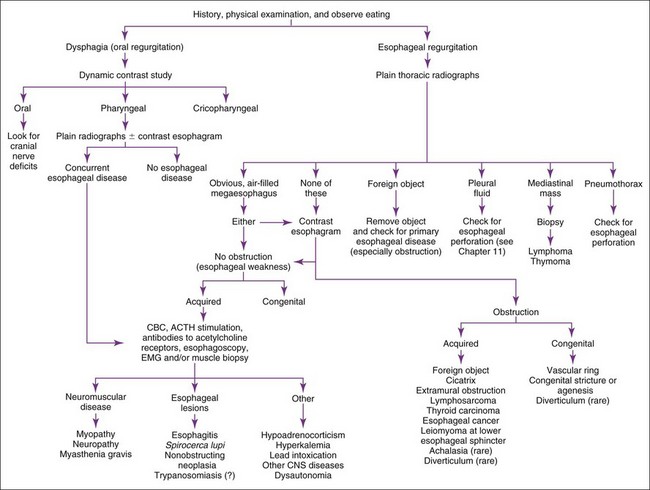

Regurgitation is usually best evaluated by history, physical examination, plain and contrast radiographs, and/or esophagoscopy (Figure 9-1). Contrast radiographs should use barium instead of iodide contrast agents unless esophageal rupture is suspected (e.g., finding air or fluid in the mediastinum on plain radiographs). The main purpose of a contrast esophagram is to distinguish esophageal motility abnormalities from anatomic lesions (e.g., obstruction, mass, inflammation, fistula). Some drugs (e.g., xylazine, ketamine) can cause esophageal hypomotility, making the radiographs potentially misleading. Esophagoscopy is insensitive for diagnosing esophageal muscular weakness but sensitive for finding anatomic lesions, differentiating intramural from extramural obstruction, identifying esophagitis, and removing foreign objects. Patients with acquired esophageal weakness should be evaluated for myopathies, neuropathies, and myasthenia gravis (generalized or localized to the esophagus). Occasionally, hypoadrenocorticism, hyperkalemia, lead poisoning, Spirocerca lupi, and selected central nervous system (CNS) disorders (e.g., distemper, hydrocephalus) may be responsible. Generalized or localized myopathies and neuropathies have several causes (e.g., trauma, dermatomyositis, thymoma, botulism, tick paralysis, systemic lupus erythematosus, nutritional factors, toxoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis). Dysautonomia occurs in dogs and cats, causing generalized dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system producing esophageal hypomotility. It is important to detect underlying disorders so that one may treat the cause rather than just the symptoms. It is also wise to evaluate patients with unexpected esophageal foreign objects (e.g., a relatively small bolus of food) for partial obstructions (e.g., subclinical vascular ring anomaly, stricture).

Vomiting

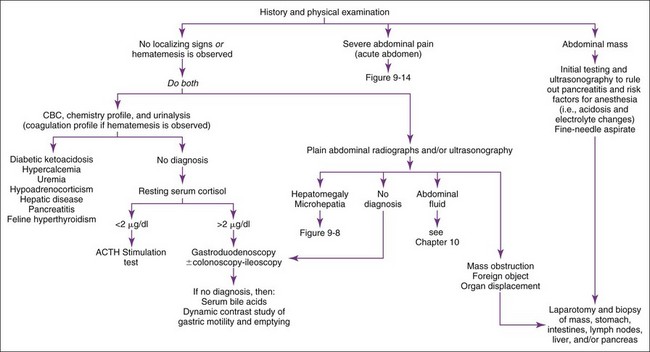

Vomiting patients are best divided into those with acute (<2 weeks) versus those with chronic (>2 weeks) vomiting. The most common categories of causes for each are listed in Boxes 9-1 and 9-2. Patients with acute vomiting often spontaneously resolve if they are supported by fluid therapy. A thorough history and physical examination are indicated first. Laboratory evaluation and/or imaging should be considered if the disease is severe or a serious disease (e.g., obstruction) is suspected. If vomiting persists, is progressive, or is attended by other clinical signs (e.g., polyuria-polydipsia [pu-pd], weight loss, icterus, painful abdomen, ascites, weakness, hematemesis), additional testing is indicated (Figure 9-2).

Box 9-1 Major Causes of Acute Vomiting in Dogs and Cats

Acute Gastritis-Enteritis (various viral or bacterial agents or toxins)

Parvoviral enteritis (dogs and cats)

Gastrointestinal (GI) Obstruction

Foreign body (obstructing or linear)

Food to which patient is allergic or intolerant

Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid

Chemotherapeutics (e.g., cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin)

Tetracyclines (including doxycycline)

Box 9-2 Major Causes of Chronic Vomiting in Dogs and Cats

Gastrointestinal Obstruction

Neoplasia (gastric or intestinal)

Gastric antral mucosal hyperplasia

Inflammatory infiltrates of the stomach or intestines (e.g., pythiosis, eosinophilic masses)

Chronic partial gastric volvulus (uncommon)

Hypomotility of stomach/intestines (physiologic obstruction) (uncommon)

Abdominal Inflammation

Chronic enteritis (dietary-responsive or antibiotic-responsive) (common)

Gastrointestinal ulceration/erosion

Peritonitis (sterile or septic)

Chronic gastritis (infrequent)

Pharyngitis (caused by upper respiratory virus in cats) (rare)

Obstruction

Abdominal radiographs and ultrasound are the best initial tests. In otherwise occult cases, contrast radiographs may be necessary, in which case barium is preferred over iodide compounds unless intestinal rupture is suspected. Barium leakage into the abdomen causes peritonitis and requires vigorous abdominal lavage at the time of surgery (see Chapter 10).

Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is an important but difficult-to-diagnose disease in cats. Chronic pancreatitis in older cats sometimes occurs in conjunction with cholangiohepatitis and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (often referred to as a triaditis syndrome involving all three organs). Vomiting is not as prominent in feline pancreatitis as it is in canine pancreatitis. Feline trypsin-like immunoreactivity (fTLI) concentrations are increased in some patients. Abdominal ultrasonography is specific, but the sensitivity is uncertain. A pancreatic biopsy may be required for a definitive diagnosis. The feline immunoreactive pancreatic lipase (spec fPL) test appears to be useful in diagnosing pancreatitis. Feline pancreatitis occasionally is due to toxoplasmosis or to feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) (see Chapter 15).

Abdominal Inflammation

Septic or nonseptic peritonitis (or inflammation of any abdominal organ) may cause vomiting. Abdominocentesis or abdominal lavage (see Chapter 10) may be needed, especially if physical examination or abdominal imaging suggests abdominal fluid. Occult cases may require laparoscopy or exploratory surgery for diagnosis.

Amylase

Drug Therapy That May Cause Hyperamylasemia

Some drugs occasionally cause pancreatitis (Box 9-3) and may cause hyperamylasemia. Corticosteroids sometimes increase serum amylase concentrations.

Lipase

Drug Therapy That May Cause Hyperlipasemia

Drugs causing pancreatitis and hyperlipasemia are the same as for amylase (see Box 9-3) plus heparin. Corticosteroids (dexamethasone) may increase serum lipase activity without histologic evidence of acute pancreatitis.

Canine Immunoreactive Pancreatic Lipase (Spec cPL)

Feline Immunoreactive Pancreatic Lipase (Spec fPL)

Gastrin

Acute Diarrhea

Patients with diarrhea are best classified into those with acute (<2 to 3 weeks) versus those with chronic (>2 to 3 weeks) diarrhea. Acute diarrhea (Box 9-4) is usually self-limiting, although some conditions may be severe and cause mortality (e.g., acute hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, parvoviral disease, hookworms, intoxication). History should explore the possibility of recent dietary change and exposure to infectious agents. Diet, bacteria, viruses, and parasites are the major identifiable causes of acute diarrhea in dogs and cats. Because intestinal parasites may contribute to any diarrheic state, fecal examinations (direct and flotation) are typically warranted in diarrheic patients. Giardiasis may require special diagnostic techniques (see Fecal Giardia Detection later in this chapter). The need for diagnostics depends upon (1) the severity of the problem (i.e., more severely ill patients require more diagnostics), and (2) the likelihood that the patient has an infectious agent that has potential to be nosocomial or zoonotic.

Box 9-4 Major Categories of Causes of Acute Diarrhea in Dogs and Cats

Giardia (sometimes difficult to diagnose)

Tritrichomonas (primarily cats)

Poor-quality food/food poisoning

Sudden dietary change (especially young animals)

Acute Viral or Bacterial Enteritis

Parvovirus (canine and feline) (common)

Coronavirus (canine and feline)

Clostridium perfringens (common)

Escherichia coli (suspected, but not proven)

Chronic Diarrhea

Chronic diarrhea should first be defined as either small intestinal or large intestinal in origin (Table 9-1). Occasionally, large and small intestines are concurrently involved. Patients with chronic diarrhea in which clinical disease is not severe are often treated with therapeutic trials before aggressive diagnostics are instituted. The specifics of the therapeutic trials are influenced by whether the patient has large or small bowel disease. Patients should usually have at least three fecal examinations at 48-hour intervals. If these tests are negative, it is still acceptable (depending upon the risk of parasites in the geographic location) to treat empirically for Giardia infection and whipworms before aggressive diagnostics are begun. Giardiasis may be particularly difficult to diagnose (see Fecal Giardia Detection later in this chapter). Adverse food reactions (i.e., allergy, intolerance, fiber deficiency) commonly cause chronic diarrhea. Dietary intolerances are a reaction to a particular substance in the diet, whereas true food allergies are immunologic reactions to specific antigens. Dietary food trials are indicated in suspected cases. There are antibiotic-responsive intestinal diseases that are also treated empirically; however, the specific therapy varies with whether the patient has large or small bowel disease (see next section). Failing to respond to empirical anthelmintic, dietary, and antibacterial therapy indicates the need for further diagnostics.

TABLE 9-1 DIFFERENTIATION OF CHRONIC SMALL INTESTINAL DIARRHEA FROM CHRONIC LARGE INTESTINAL DIARRHEA

| SMALL INTESTINAL DIARRHEA | LARGE INTESTINAL DIARRHEA | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (very important criterion) | Expected | Uncommon except with severe disease (e.g., histoplasmosis, pythiosis, or cancer) |

| Polyphagia | Often present | Uncommon |

| Vomiting | May occur | Occurs in 10%–20% of patients |

| Volume of feces | May be normal or larger than normal | May be normal or smaller than normal |

| Frequency of defecation | Normal to slightly increased | Normal to markedly increased, may have many small defecations per bowel movement |

| Slate-gray feces (steatorrhea) | Rare | No |

| Hematochezia | No | Sometimes |

| Melena | Rare | No |

| Mucoid stools | Rare (unless ileum is diseased) | Often present |

| Tenesmus/dyschezia | Rare | Sometimes |

Large Intestinal Disease

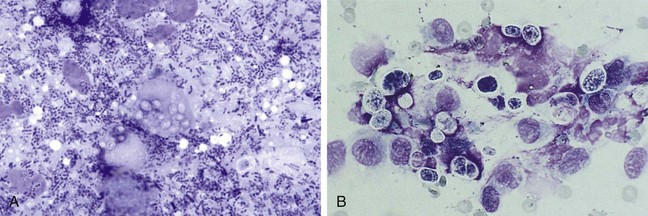

Large intestinal disease has different parasites (i.e., Trichuris vulpis, Tritrichomonas fetus), dietary problems (i.e., fiber-responsive diarrhea), and bacterial problems (i.e., so-called clostridial colitis that responds best to tylosin or amoxicillin) than small bowel disease. Once parasitic, dietary, and “clostridial colitis” are eliminated by diagnostics and therapeutic trials, additional diagnostic steps, such as rectal mucosal scrapings (not swabs) with cytologic examination (Figure 9-3) might be appropriate. Persistent large intestinal disease that fails to respond to these therapeutic trials or that is associated with hypoalbuminemia or obvious weight loss is usually an indication for abdominal ultrasound followed by fine-needle aspiration and/or colonoscopy-ileoscopy plus biopsy. Rigid colonoscopy of the descending colon is adequate for diagnosis in most cases. Flexible endoscopy allows access to the descending, transverse, and ascending colon; ileocolic valve; cecum; and ileum. If flexible endoscopy is unavailable, abdominal ultrasonography may reveal lesions in areas not accessible with rigid endoscopy.

Small Intestinal Disease

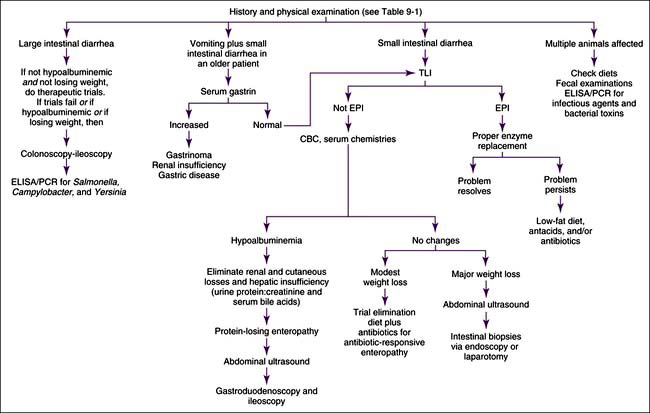

Small intestinal disease has different parasites (e.g., Giardia), dietary problems (e.g., lymphangiectasia), and bacterial problems (i.e., so-called antibiotic-responsive enteropathy [ARE] or dysbiosis that may respond to a variety of antibacterials) than large bowel disease. Chronic and severe small intestinal diarrhea necessitates differentiation of maldigestion, protein-losing enteropathy (PLE), and malabsorptive disease without protein loss (Figure 9-4). Weight loss and diarrhea are usually present, but some patients only have weight loss.

Protein-Losing Enteropathy

PLE is uncommon in cats but seen with some regularity in dogs. PLEs are classically described as causing panhypoproteinemia. However dogs with diseases causing hyperglobulinemia (e.g., chronic skin disease, rickettsial disease, heartworm disease) and some breeds (e.g., basenji dogs) may have only hypoalbuminemia because the serum globulin concentration is initially increased, and even though much of this fraction is lost into the intestines, the amount remaining in the blood keeps concentrations in the normal range. If red blood cells (RBCs) are also being lost, iron deficiency anemia may occur (see Chapter 3).