Chapter 19 Flock and Herd Health

Definition of Flock Health

• Prevention of common disease conditions through the use of appropriate vaccination schedules (Table 19-1)

• Management strategies that minimize risk factors for disease occurrence

• Provision of appropriate levels of nutrition for the stage of production

TABLE 19-1 Basic Vaccination Program for Sheep

| Timing | Immunization/Scheduled Management Practice(s)/Intervention(s) |

| PREGNANT EWES | |

| In endemic areas, vaccinate ewe lambs or previously vaccinated animals against Campylobacter and Chlamydia (Chlamydophila) abortion. | |

| Vaccinate for Clostridium species (C. perfringens type C and D, C. novyi, C. sordelli, C. chauvoei, C. septicum, C. tetani) | |

| Repeat Chlamydophila and Campylobacter vaccinations for previously unvaccinated animals and give yearly booster to other ewes | |

| LAMBS | |

| Immunize lambs from immunized dams for Clostridium species (C. perfringens types C and D, C. novyi, C. sordelli, C. chauvoei, C. septicum, C. tetani) | |

| Immunize lambs from nonimmunized dams for Clostridium species (C. perfringens types C and D, C. novyi, C. sordelli, C. chauvoei, C. septicum, C. tetani) | |

| RAMS AND YEARLINGS | |

| Vaccinate at the same time as for ewes, with an emphasis on Clostridium species. Vaccines against rabies should be given in endemic areas. | |

Veterinary visits usually are scheduled in accordance with timing of major production events (e.g., before breeding; in midpregnancy; before, during, and after lambing; in midsummer). During the first visit, the veterinarian assigns a body condition score (BCS) to the ewe flock, which is imperative for making nutritional and feeding management recommendations. Evaluation of the rams should include both a general physical examination and fertility assessment (see Chapter 8). A written record should indicate the ram’s BCS and weight, problems identified on the physical examination, and an action plan to address any problems that are crucial to breeding. The midpregnancy visit focuses primarily on ultrasound pregnancy determination and fetal counting and aging. On the basis of these results, the veterinarian can develop a plan for feeding ewes appropriately and economically as appropriate for fetal numbers and stage of pregnancy (see Chapter 2). This visit can be crucial in preventing metabolic disease in late pregnancy. The visit, examination, and herd/flock recommendations for the ewe in late pregnancy entails a review of the nutrition of the late-gestation ewe so that she can perform up to her genetic potential at lambing.

Properly fed ewes produce maximal amounts of colostrum and milk, give birth to thrifty lambs with minimal difficulty, and demonstrate excellent mothering abilities. The final 2 months of pregnancy are crucial to successful lamb growth and survivability. During this visit, the veterinarian can review strategies to prevent disease such as vaccinating against clostridial infections 4 weeks before lambing and providing a clean environment. The management plan at lambing time, including the layout and use of facilities, also should be reviewed. This plan should include education of farm personnel to recognize the need for intervention for lambing problems (Tables 19-2 and 19-3).

TABLE 19-2 Generic Management Calendar for Spring Kidding and Lambing

| January | Evaluate range and forage conditions; monitor body condition of does and ewes and supplement if necessary; ensure adequate intake of minerals, salt, and water; vaccinate during the final month of gestation for clostridial disease and any other endemic diseases. |

| February | Begin supplemental feeding of pregnant females and consider prebirthing shearing; begin birthing; check teats for milk and identify lambs and kids; ensure ingestion of adequate colostrum by lambs and kids; institute pre- and postbirthing strategic deworming; maintain an ionophore in feed or mineral mixture before and after birthing to decrease coccidial contamination of pasture. |

| March | Separate singles from twins; confine and feed females with their lambs and kids as needed; feed does and ewes to maintain milk production; continue strategic deworming program. |

| April | Continue to feed a supplement to lactating does and ewes; monitor for parasites with FAMACHA scoring and “smart drenching.” |

| May | Wean small, stunted lambs and kids; discontinue supplemental feeding of does and ewes; monitor internal parasites (with FAMACHA and fecal egg counts using McMaster technique). |

| June | Continue parasite control program with FAMACHA monitoring. |

| July | Monitor internal parasites; watch for signs of heat stress; wean lambs and kids. |

| August | Continue parasite control program; continue weaning lambs and kids; supplement replacement does, ewes, bucks, and rams; select replacement males and females; identify and cull unsound and inferior animals; perform breeding soundness evaluation in males. Criteria for culling include the following: |

| September | Begin supplemental feeding of females and males on fresh green pasture with ½ lb feed/head/day for 2-3 weeks before and after males are placed with females; continue parasite control program. |

| October | Begin breeding; maintain good male-to-female ratio, depending on pasture size and conditions; continue supplemental feeding of females for 2-3 weeks after start of breeding season. |

| November | Evaluate range and forage conditions; determine females’ body condition and plan winter supplemental and feeding program; control internal and external parasites; remove some of males’ feed to regain body condition; determine pregnancy status and number of fetuses. |

| December | Evaluate body condition of does and supplement feed if needed; monitor internal and external parasites. |

TABLE 19-3 Seasonal Veterinary Management

| Period in Seasonal Cycle | Veterinary Visit Assessments |

|---|---|

| Prebreeding | |

| Midpregnancy | |

| Prelambing | |

| Midsummer |

BCS, Body condition score.

Minimum standards and target production parameters should be set for morbidity, mortality, culling, and growth rates (Table 19-4). A quality assurance program also should be designed for the flock. To date, the sheep-packing industry has not required producers to participate in flock quality assurance programs, but such programs exist and will become more common in the future as a result of consumer demand. Quality assurance programs educate producers in good production practices and encourage cooperation between practitioners and area producers. Table 19-2 presents a sample management calendar for spring lambing.

| Production Parameter | Target |

|---|---|

| PREGNANCY | |

| Ewes | More than 95% |

| Ewe lambs | More than 75% |

| Visible abortion | Less than 5% |

| LAMBING | |

| Ewes | More than 90% |

| Ewe lambs | More than 70% |

| Stillbirths | Less than 2% |

| Weaning | More than 95% |

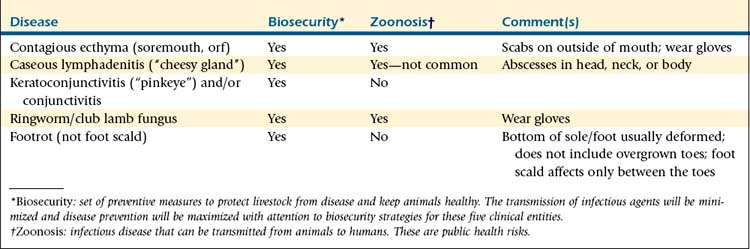

Barnyard Biosecurity

• Do not haul disease home or to the market. Table 19-5 lists some of the diseases that should “stay home” on the farm until the animal fully recovers.

• Isolate new animals for 2 to 4 weeks. Have no contact between new animals and the resident farm herd or flock animals during this time. Prevent introduction onto farm by keeping a closed herd or flock, and purchase animals from known sources (Table 19-6).

• Restrict access to the farm: post signs for vehicle and foot traffic control; keep a visitor log; don’t track disease in—wear different shoes, clothes, and hat to livestock auction market or public area and change before working with livestock.

• Provide good nutrition (water, feed, and minerals) and management plan (including vaccination, deworming, and the like) to maintain a healthy herd or flock.

• Report animals with unusual illness or those that are not responding to treatment to a local veterinarian, the state veterinarian, or the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Veterinary Services. Early detection may save animal lives.

Vaccination Programs

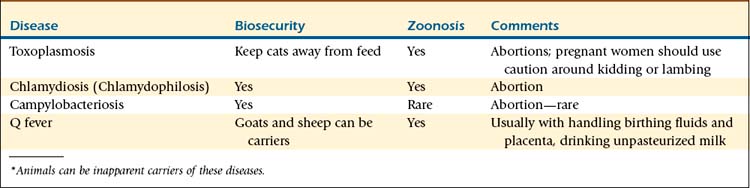

Other diseases that have an available vaccine labeled for use in sheep in the United States include some infections associated with abortion such as those caused by Campylobacter spp. and Chlamydia (Chlamydophila) psittaci; multisystem diseases such as caseous lymphadenitis, musculoskeletal diseases such as footrot, neurologic diseases such as rabies, and integumentary diseases such as contagious ecthyma (soremouth). If past history indicates that the flock is at risk for a disease, such vaccines can be included in an immunization program (see Table 19-1), which can be modified for the individual farm.

Internal Parasite Control Programs

The epidemiology of pathogenic sheep nematodes and protozoal species depends on the climate of the region; therefore internal parasite control must be tailored to the region of the country in which the flock resides. Parasite control programs also must take into account whether the flock is confined, pastured, or rotationally grazed. Successful programs implement regular monitoring of the efficacy of anthelmintics, sheep-friendly handling equipment for anthelmintic delivery such as well-designed pens and chutes, and use of automatic syringes or drench guns. Other components of a parasite control program include the use of multiple strategies to minimize the buildup of nematode eggs on pasture; this aim can be achieved by deworming ewes with larvicidal doses during winter housing, at 4 weeks after spring turnout, and at 3 weeks into lambing. Control also is enhanced by the use of management practices that reduce reliance on chemical anthelmintics, such as FAMACHA “Smart Drenching,” grazing clean ground with weaned lambs, “vacuuming” nematode eggs by grazing the previous year’s sheep pastures with cows or horses, and selecting for and breeding nematode-resistant sheep (see Chapter 6).

When the flock must graze close to the ground and nutritional input is marginal, nematode infestation may escalate, typically with development of clinical parasitism in stressed sheep. The veterinarian and the producer should create an annual calendar that details the entire flock health program. The producer should record details about any procedures performed in the production groups. Box 19-1 summarizes recommendations to improve parasite control. Table 6-1 shows some commonly used anthelmintics and coccidiostats useful in parasite control for sheep and goats.

BOX 19-1 Summary of Recommendations for Parasite Control*

1. Make certain that the anthelmintic or combination of anthelmintics used on the farm actually works (kills at least 90% of the viable worms). Check for resistance with fecal egg counts before and after deworming.

2. Utilize FAMACHA “smart drenching” in the spring and continue to assess every 2-4 weeks until the hazard of Haemonchus infestation no longer remains in cold weather.

3. Use strategic deworming. Deworm the flock while the parasites are in hypobiosis and are being transmitted at low levels (i.e., the winter). This strategy reduces the frequency of exposure to deworming products.

4. Employ pre- and postbirthing deworming starting 1 month before birthing at 2- to 4-week intervals and ending 2-4 weeks after the final lamb or kid is born.

5. Tactical dewormings (based on increased levels of parasite eggs or 10-14 days after rainfall) enhance the effectiveness of a parasite program.

6. Graze above 4 inches; use “clean” or safe pastures when possible (aftermath of crops, annual forage such as chicory); utilize rotational grazing or cograzing with cattle or horses. (Beware: Permanent pastures promote parasites.)

7. Deworm new animals and place them in a nonpasture environment such as a dry lot or barn after treatment for as long as 72 hours before moving them to a safe pasture. Check fecal egg count 10-14 days after treatment for fecal egg shedding

8. Rotate anthelmintics yearly if effective drugs are available.

9. Do not underdose. Determine dose for the heaviest animal in a production group.

10. Identify and select individual animals resistant to internal parasites for flock/herd retention and breeding.

External Parasite Control Programs

Keds and biting lice are the prevalent external parasites of sheep. Many sheep flocks have not introduced these parasites. In these flocks, all newly purchased sheep should be treated prophylactically while they are in isolation to prevent parasite introduction. In flocks in which either parasite is endemic, all sheep on the property should be treated at the same time, so that one group does not serve as a reservoir for reintroduction. Treated sheep should be kept out of any contaminated buildings for 2 weeks, because buildings also can serve as reservoirs during this time. Further treatments should not be necessary after the whole flock is properly treated. The flock should be monitored for ectoparasite infestation after reintroduction from carrier sheep or after improperly applied whole flock treatment. An external parasite control program is described in Chapter 6.

Flock Health Monitoring

• Ram-to-ewe ratios at breeding

• Ewe and ram mortality numbers and reasons

• Pre- and postweaning lamb mortality rates and reasons

• Ram morbidity and treatment outcomes (especially those that pertain to breeding use)

The average BCS of the ewe flock should be recorded at breeding, lambing, and weaning (see Chapter 2). If target scores are not achieved, the producer and the veterinarian need to determine why and make appropriate management changes. If the correct changes are implemented, future scores should improve, with consequently enhanced production.

Culling and Disposal Practices

Culling practices should be based on genetics, productivity, poor fertility, substandard growth, parasite and disease susceptibility, and disease (e.g., footrot, caseous lymphadenitis, scrapie, ovine progressive pneumonia). Not all sick or thin animals survive to the point of culling. Each operation must have a plan for carcass disposal. Carcass disposal procedures used should be legal in the area and state, environmentally friendly for the size of the animal and number of carcasses, and practical for the producer. Many states legally permit sheep composting (see Box 20-2). A sheep of any size will turn into compost if the procedure is done correctly. With some diseases (e.g., scrapie, foot-and-mouth disease), carcasses may by law require incineration.

Neonatal Care

Equipment and facilities should be prepared and organized before the start of lambing. Records to guide improvements in management should be kept and used. Regardless of whether animals are raised in confinement or on pasture, periparturient ewes should be grouped together according to expected lambing dates and fetal numbers, if available. These groupings enable tailored levels of feeding, which are economically justifiable, minimize the occurrence of metabolic disease, and prevent fetal under- or overfeeding. The result is the birth of viable lambs. When lamb losses occur, postmortem examination by the local veterinarian or veterinary diagnostic center in representative cases is recommended. Management changes should be based on the necropsy findings (see Chapter 20).

Foot Care

Part of the annual care of sheep should include assessment of the condition and length of their hooves. Depending on the terrain and rainfall in the area, some flocks do not require annual hoof trimming, but most flocks in the midwestern and eastern regions of the United States will need regular trimming. The timing of this procedure is not important so long as hoof overgrowth, which predisposes affected animals to other foot problems such as foot scald, toe abscesses, and footrot, is not allowed to occur. Many farm flocks trim the ewes’ feet around lambing time while they are in confinement and being handled regularly. Many range flocks only require foot trimming of a few individual animals. These sheep wear their feet down adequately on dry, rough terrain, and some breeds are predisposed to slower foot growth. Rams should have their feet trimmed 4 to 8 weeks before breeding. Trimming in the week before the start of breeding is contraindicated in case overzealous trimming causes temporary lameness. A generic footrot prevention program is presented in Box 11-2 (see also Chapter 11).

Water Availability and Design

Water is an essential nutrient for sheep of all ages. It should be of good quality and readily available. Cleanliness, taste, impurities, and temperature all affect consumption. Key times during which the quality of the water supply has a direct influence on the productivity or health of the animal are the lambing and finishing phases, late pregnancy, and lactation (see Chapter 2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree