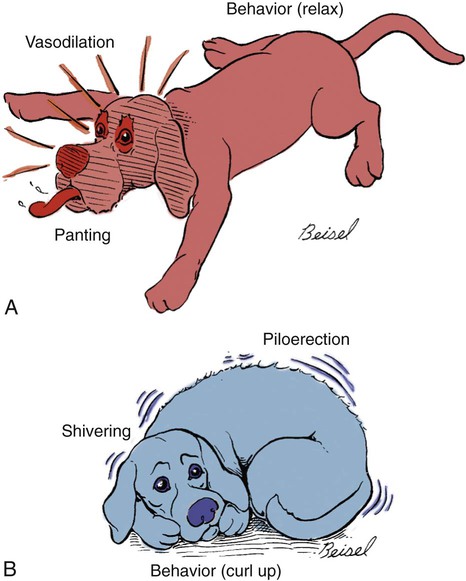

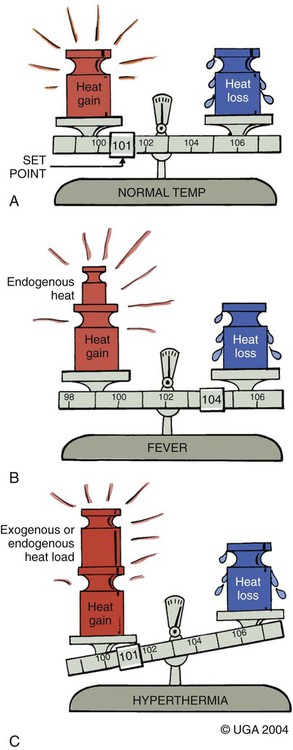

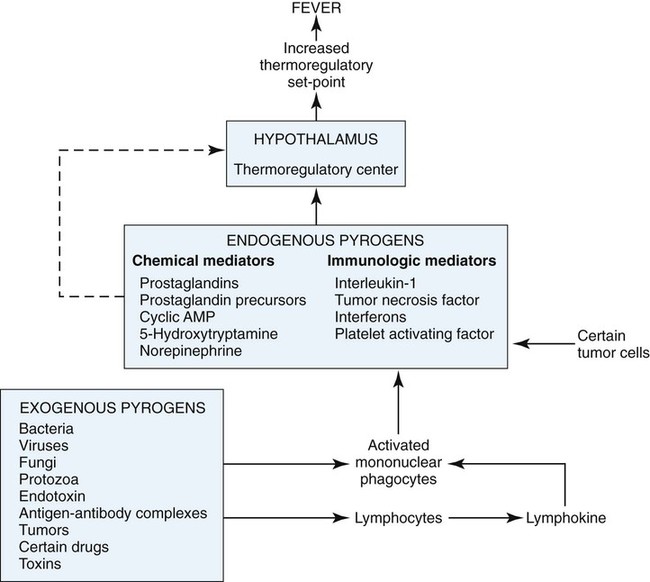

Fever is a common clinical finding in patients with infectious, parasitic, inflammatory, immune-mediated, or neoplastic disease. In many of these patients, fever is accompanied by other more specific or localizing clinical signs, and the cause of the fever is determined with simple diagnostic tests. In some cases, the cause of the fever is not readily apparent, but it resolves spontaneously or in response to empiric therapy, often with antibacterials. In a small subset of patients, the cause of fever is not easily determined and not therapeutically responsive, and the problem becomes persistent or recurrent. Such cases of fever of unknown origin (FUO) present a particular diagnostic challenge in both human and veterinary medicine.3,24,34,35,57 This chapter outlines the pathophysiology of fever and presents an approach to the small animal patient with FUO. Body temperature is determined by the set-point of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center. Thermoregulation depends on sensory information from external and internal thermoreceptors and on physiologic and behavioral effector mechanisms that control heat production and heat loss. Body heat is lost through the skin and the respiratory tract and can be gained by transfer from the environment or generated by muscle activity or body fat catabolism. Body temperature is decreased by panting, cutaneous vasodilation, seeking shelter, and remaining inactive (Fig. 95-1, A). In a cold environment, body temperature is maintained by shivering, postural changes, piloerection, and cutaneous vasoconstriction (see Fig. 95-1, B). In a normal animal, these mechanisms balance heat loss and heat gain and keep the body temperature as close as possible to the normal hypothalamic set-point (Fig. 95-2, A). Hyperthermia refers to any increase in body temperature above normal. In true fever, the hypothalamic set-point is elevated, and body temperature is increased by enhanced heat production and conservation. Heat gain and heat loss mechanisms now act to maintain body temperature at the new set-point (see Fig. 95-2, B). In nonfebrile hyperthermic conditions, the hypothalamic set-point is not altered, and elevated body temperature is the result of increased and unregulated heat gain or heat production or impaired heat loss (see Fig. 95-2, C). Examples of nonfebrile causes of hyperthermia include heat stroke, exercise-induced hyperthermia, malignant hyperthermia, seizure activity, and hypermetabolic disorders. Hyperthermia of this type can progress to multiorgan-dysfunction syndrome caused by an interplay among circulatory disturbances, hypoxia, increased metabolic demand, cytotoxicity of high temperature, and activation of inflammatory and coagulation cascades.11 Fever is mediated by the action of pyrogens. Exogenous pyrogens (infectious agents and their products, tumors, drugs, and toxins) stimulate inflammatory cells to release endogenous pyrogens (cytokines such as interferons, interleukin [IL]-1β and -6, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α), and this leads to induction of cyclooxygenase 2 activation of the arachidonic acid cascade, with enhanced synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 is synthesized by hypothalamic vascular endothelial cells and acts on thermoregulatory neurons to raise the hypothalamic set-point. The thermoregulatory set-point is located in a rich vascular network called the organum vasculosum laminae terminalis in the preoptic rostral hypothalamus that possesses little if any blood-brain barrier. Endothelial cells within this area are thought to release arachidonic metabolites themselves, and then metabolites of cyclooxygenase such as PGE2 are thought to diffuse the short distance to the hypothalamic neurons and induce fever. PGE2, which itself is not neurally active, can induce production of cAMP or other neurotransmitters, which, in turn, raises the temperature set-point of the body. Additional evidence suggests that the thermoregulatory center may also be stimulated via vagal fibers that respond to release of cytokines locally released in tissues.71 The pathogenesis of fever is summarized in Fig. 95-3. FUO in both human and veterinary medicine can be most usefully defined as fever that does not resolve spontaneously in the period expected for self-limited infection and the cause of which cannot be ascertained despite considerable diagnostic effort.3 In veterinary medicine, this diagnostic effort typically includes a complete history and physical examination, complete blood (cell) count (CBC), chemistry, urinalysis, and radiography. It is also common for veterinary patients to receive antibacterial therapy to address possible bacterial infection before it is determined that the origin of the fever is unknown. Although fever is frequently associated with infectious diseases, the same response can be elicited by many inflammatory, immune, or neoplastic disorders. Because the list of differential causes for FUO is extensive, grouping these causes into broad categories based on the underlying disease process is useful. Table 95-1 shows the causes of FUO divided into infectious and parasitic diseases, Table 95-2 summarizes inflammatory and immune-mediated causes of FUO, and neoplastic and miscellaneous causes are listed in Table 95-3. In the human medical literature, the causes of FUO are typically distributed as follows: 30% to 40% are infectious, 20% to 30% are neoplastic, 10% to 20% are rheumatologic, 15% to 20% are miscellaneous, and 5% to 15% are undiagnosed. Broadly similar distributions have been reported in veterinary patients, but variation can be found among reported case series.57 This variation may be caused by both the particular clinical interests of the authors and their geographic locations. Published case series are also exclusively or predominantly canine.31,57 Infection, immune-mediated disease, and neoplasia are the most common causes of FUO in the dog, whereas FUO in cats appears most likely to be infectious in origin.34,51 TABLE 95-1 Infectious and Parasitic Diseases Associated with Fever of Unknown Origin B, Both dog and cat; C, predominantly cat; D, predominantly dog. TABLE 95-2 Inflammatory and Immune-Mediated Diseases Associated with Fever of Unknown Origin B, Both dog and cat; C, predominantly cat; D, predominantly dog. TABLE 95-3 Neoplastic and Miscellaneous Diseases Associated with Fever of Unknown Origin B, Both dog and cat; C, predominantly cat; D, predominantly dog. Fever is rarely an isolated finding in these cases, given that IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 induce a large number of complex immunopathologic events. These events contribute to the acute-phase response, which is a vital part of the innate immune system. Important acute-phase proteins include C-reactive protein, serum amyloid-A, haptoglobin, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, ceruloplasmin, and fibrinogen. The former proteins are synthesized by the liver and are increased in the acute-phase response, whereas synthesis of other proteins such as albumin and transferrin is decreased. See pathophysiology of sepsis (Chapter 36) for a thorough review of many of these immunopathologic mechanisms. Although some patients with FUO may have uncommon infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic diseases, many patients are ultimately found to have an unusual or early manifestation of a common disorder.3 Therefore, the clinician must approach these cases in a systematic fashion that allows for the detection of any potential cause of fever while avoiding unnecessary testing and minimizing patient discomfort. A diagnostic plan for FUO may be based on consideration of the disease process, as outlined in Tables 95-1, 95-2, and 95-3. A complementary approach is summarized in Table 95-4, in which the causes of FUO are grouped according to anatomic or body system location. This approach is helpful in selecting diagnostic tests, particularly when localizing clinical signs are absent or subtle. By combining a disease process and anatomic approach, the clinician can develop a comprehensive diagnostic plan for any FUO patient. TABLE 95-4 Causes of Fevers of Unknown Origin Grouped by Body System or Region ANA, Antinuclear antibody; CBC, complete blood cell count; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; FeLV, feline leukemia virus; FIP, feline infectious peritonitis; FIV, feline immunodeficiency virus; GI, gastrointestinal; IV, intravenous; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RF, rheumatoid factor. Table adapted, with permission, from Ref. 57. In addition to including appropriate diagnostic tests, the diagnostic plan should follow a sequence that is both logical and flexible. The typical diagnostic plan will begin with tests that are safe, simple, inexpensive, and easy to interpret. A staged approach can be used to guide the selection of diagnostic tests, and examples are outlined in Box 95-1.

Fever

Pathophysiology of Fever

Fever of Unknown Origin

Etiology of Fever of Unknown Origin

Type of Infection

Examples

Systemic bacterial

Infective endocarditis (D), bacteremia from inapparent focus (B)

Localized bacterial

Infective endocarditis (D), pyelonephritis (B), prostatitis (D), stump pyometra (B), pyothorax and lung infections (B), pancreatitis (D), hepatic abscess or cholangiohepatitis (B), peritonitis (B), septic meningitis (B), septic arthritis (B), osteomyelitis (B), diskospondylitis (B), tooth root abscess (B), other abscesses or cellulitis (B)

Specific bacterial

Leptospirosis (D), Lyme disease (D), brucellosis (D), mycobacterial infection (B), bartonellosis (B), plague (C), L-form infections (B)

Viral

Feline leukemia virus infection (C), feline immunodeficiency virus infection (C), feline infectious peritonitis (C), feline calicivirus infection (C), canine distemper virus infection (D), canine influenza virus infection (D)

Rickettsial and mycoplasmal

Ehrlichiosis (B), anaplasmosis (D), hemotrophic mycoplasmosis (B), mycoplasmal infections (B)

Fungal

Blastomycosis (B), cryptococcosis (B), coccidioidomycosis (B), histoplasmosis (B), aspergillosis (D)

Protozoal

Toxoplasmosis (B), neosporosis (D), hepatozoonosis (B), babesiosis (B), leishmaniasis (B)

Type of Disease

Examples

Immune-mediated

Systemic lupus erythematosus (D, rare in C), idiopathic immune-mediated polyarthritis (B), rheumatoid arthritis (D), polymyositis (B), steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis (D), vasculitis (B)

Inflammatory

Nodular panniculitis (B), lymphadenitis (B), steatitis (D), pancreatitis (B), inflammatory bowel disease (B), granulomatous diseases (B), hypereosinophilic syndromes (B)

Type of Disease

Examples

Solid tumors

Several, including hepatic tumors, gastric tumors, lung tumors, bone tumors, metastatic disease, and any necrotic tumor (B)

Hematopoietic tumors

Lymphoma (B), leukemia (B), myeloma (B), malignant histiocytosis (B)

Miscellaneous

Metaphyseal osteopathy (D), panosteitis (D), portosystemic shunt (B), pansteatitis (C), drug reaction (B), shar-pei fever (D)

Development of a Diagnostic Plan for Fever of Unknown Origin

Body System or Region

Appropriate Diagnostic Tests

Examples

Blood and hematopoietic

CBC, blood film evaluation, bone marrow aspirate, urinalysis, ophthalmic fundic exam, bone marrow biopsy, serum protein electrophoresis, FeLV and FIV tests, other serology, blood culture

Leukemia, myeloma, bacteremia, drugs, ehrlichiosis, granulocytopathy, hypereosinophilic syndromes, hemotrophic mycoplasmosis, metastatic neoplasia, walled-off hematomas

Lymphoid

Lymph node palpation, lymph node cytology and culture, lymph node biopsy, lymphangiography

Lymphoma, lymphadenitis, lymphangitis

Cardiovascular

Auscultation, radiography, angiography, electrocardiography, echocardiography, vascular biopsy, pericardiocentesis, blood culture

Endocarditis, pericarditis, vasculitis

Respiratory

Radiography, transtracheal or endotracheal wash, fine-needle aspiration, biopsy, ultrasonography, bronchoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage, CT, thoracoscopy

Bronchial foreign body, fungal or bacterial pneumonia, neoplasia, pulmonary embolism

Nervous system

Fundic and neurological examination, radiography, myelography, CT, MRI, nerve or muscle biopsy, CSF analysis

Toxoplasmosis, fungal infection, steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis, FIP

Musculoskeletal

Radiography, arthroscopy, blood culture, arthrocentesis, synovial membrane biopsy, bone biopsy, RF, ANA

Immune-mediated polyarthritis, myositis, panosteitis, diskospondylitis

Gastrointestinal

Radiography, barium contrast studies, ultrasonography, rectal examination, fecal cytology, rectal cytology, fecal culture, oral and dental radiographs, pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, trypsin-like immunoreactivity, endoscopy, laparoscopy, exploratory surgery, biopsy

Neoplasia or abscess anywhere in GI tract, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, fungal disease, portosystemic shunt, hepatobiliary, gastric, or splenic inflammation

Urogenital

Urinalysis, urine culture, prostatic wash and ejaculate cytology and culture, radiography, ultrasonography, IV pyelography, cystography, cystoscopy, vaginoscopy, cytology, biopsy

Prostatitis, stump pyometra, pyelonephritis, orchitis

Endocrine

Biochemical profile, thyroid hormone

Hyperthyroidism

Pleural or peritoneal cavity

Radiography, ultrasonography, fluid analysis, cytology, microbial culture, biopsy

Pyothorax, FIP, peritonitis, neoplasia

Skin

Physical examination, cytology, biopsy, microbial culture, fistulography

Abscess, fungal infection, nodular panniculitis, vasculitis, actinomycosis, nocardiosis, mycobacteriosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Fever