34 Feline uveitis

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

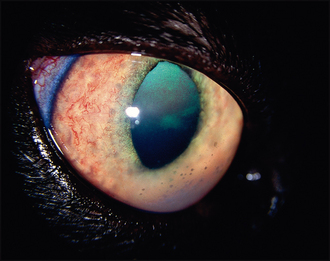

The eye will appear cloudy. This can be due to a combination of aqueous flare, keratic precipitates, hypopyon, cataract and vitreal opacification (Figure 34.1). Oblique examination of the eye, but with the light source directed perpendicular, will assist in locating the site of opacity. Keratic precipitates tend to accumulate ventrally on the corneal endothelium. When the cat is on the examination table and you are looking down at it these opacities might not be obvious. However, if you get the cat to sit at the edge of the table and look down, while you squat on the floor and look up into its eyes, the ventral half of the eye will be more easily examined. Also when looking for keratic precipitates it is important to check both eyes. Many cases of uveitis present unilaterally but on careful examination it is clear that both eyes are affected to differing degrees.

Aqueous flare will vary from just a slight haze to the anterior chamber through to full blown hypopyon obscuring further intraocular examination. Similarly, most cats will have a clear lens, but in chronic cases a total mature cataract can be present. Vitreal inflammation, hyalitis, is quite common in chronic uveitis cases and will most frequently be centred behind the lens – a pars planitis. Without careful examination this can be confused with cataract. Some cases of anterior uveitis will also have chorioretinitis as well. Thorough fundus examination, after pupil dilation with tropicamide, might reveal both active and inactive chorioretinal lesions.